Around the Bend to Evaluation

advertisement

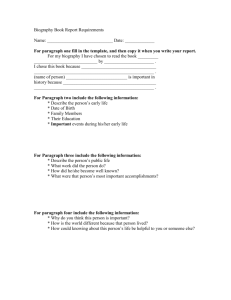

QuickTi me™ and a T IFF (Uncom pressed) decom pressor are needed to see t his pict ure. Learner-Centered Teaching: Helping Students to Succeed, Part 2 Qatar University May 2, 2007 Chris M. Anson North Carolina State University Sharing Responses • Please share your responses to the case assignment from yesterday at your tables. • Be ready to share some ideas with the larger group when we reconvene. Supporting Learning in Larger Projects • Informal summaries • In-class oral progress reports and • Metacommentaries and reflection • “Microthemes” and short, lowstakes papers • Planning and invention exercises • Peer response sessions • Self-assessments • Sharing and discussing evaluation criteria or standards Teacher gives assignment Student works alone A traditional model of writing assignments Student turns in best effort (usually a first draft) Teacher reads/views (edits) the result Student is supposed to learn by trial and error But the next assignment is different . . . . Your Instructional Goals Your Assignment Design Students' First Attempts A goal-based model of writing that includes response and revision Revision Conference or Focus Students' Revisions Final Draft Your Responses/Suggestions High Poten tial for Leaning Some Poten tial for Learning drafting, rethinking, and revising Submission for final evaluation Start of assignment Places for Support first attempt prelim. exploration & brainstorming practicing skills & strategies topic selection first full draft second & nth drafts most common “rewrite” Your Turn . . . . • Someone at your table please volunteer to discuss your assignment • Focus on the nature of the support that you provide for learning from the assignment • How can you maximize learning through activities that students engage in before the first draft and between the first and final draft? Evaluation for Support? Design Assignments Develop Goals for Student Learning Low-stakes/ informal Evaluate Learning High stakes/ formal Create Supporting Activities for Student Learning Operative Questions Learning Goals What new knowledge, skills, and processes do you want students to be able to know or use? Assignment Design What aspects of your assignment help to accomplish those goals? Supporting Activities What activities support the development of the assignment? Assessment How do you judge whether the learning goals are reflected in students’ products? Create a Scoring Guide (“Rubric”) Categorical • Based on categories that match the goals or characteristics of performances • Assumes that we can judge the quality of these features separately • Assigns separate scores to each category Descriptive • Based on clusters of characteristics that generalize levels of performance • Assumes it is hard to separate features from each other • Assigns scores based on “impressions” of the whole What’s “Behind” a Rubric? • Rubrics are “shorthand” methods for categorizing desired features of responses • Every category has more specific, underlying features • If students don’t understand a category, they can’t use it productively • Supporting the use of assessment rubrics for students means helping them to internalize the underlying features [ ] reflects thoughtful response/critical analysis What is this? Essential: Define Criteria • • • • • What does it mean to “analyze”? What’s “good scientific observation?” What’s “style appropriate to the occasion or audience?” What characterizes “strong use of secondary source material? What’s “evidence that you studied the material in the manual”? How Far to Go? • • Based on the assignment and your comfort level, decide how specific you want your criteria to be in your scoring guide Consider “front-loading” the specific features into your teaching instead (help students to internalize criteria by working with them in class) Use Evaluation for Support • Evaluation criteria are often hidden from view • If they are available, they are often generalized across various assignments • How can we help learners to internalize standards for success? How can we make evaluation productive? Explain and Work With Categories Thoughtful response/critical analysis: The thoughtful response shows that you have read the material thoroughly and reflected on it fully. It demonstrates a careful and thorough application of the question to the material at hand. It may offer some interesting and creative insights that are supported by material in the text. The response will be generally well written and structured, with an allowable informality considering the nature of the task, and there will be few errors that distract or get in the way of meaning. Making Criteria Formative • Create evaluative criteria with direct reference to your assignment goals. • Make the criteria available to students in advance of their beginning the assignment. • Use the criteria: • • • • • in the evaluation of sample drafts In any supporting activities that guide students’ work in the response questions you give students In the collaborative formulation of criteria In the annotated models you provide on paper or electronically Suggestions: Assessment • Always craft criteria from your goals. • Avoid collecting and grading first drafts: use revision and peer review to improve writing before you see it. • Match your evaluation methods to the formality of your assignment. • Give students your criteria in advance, or create them as a class. Make criteria productive. Responding to Writing Criterion-based response • What could the writer do to improve the paper’s organization or structure? • What could the writer do to make his/her transitions smoother? Responding to Writing Reader-based response • List three words that best capture the image the writer conveys of him/herself in the paper. • As a reader, were you persuaded by the argument in the paper? What was persuasive and why? Responding to Writing Descriptive prompts • Summarize, in your own words, the main point or idea in the writer’s paper. • Describe what you think are the most convincing information the writer used to support or illustrate that point. Note the difference “Move the third paragraph to the front.” “There’s a dangling modifier in line 12.” “Get rid of the clinical style.” “Your style is too bureaucratic for a story.” “I was sort of confused by this section.” “Did you mean to sound so passionate?” “I felt distanced by the language.” “I couldn’t see you anywhere in here.” Focus on text Focus on reader’s experience Other Strategies Do/Say Focus The teacher (or peer responder) works through a paper paragraph by paragraph. For each, the reader writes what the paragraph says and what the paragraph does: “This paragraph says that people are silly to believe in ancient superstitions. It repeats the point made in paragraph #3. Other Strategies “Heard/Noticed/Wondered” Focus • I heard . . . Summarize the writing. What’s the main idea? What is communicated? • I noticed. . . Describe what stood out. What attracted your attention? What will you remember? • I wondered… Describe gaps, puzzles, other information you wanted, confusions, things that disturbed you. Example Dear Karina, When reading your essay, I heard that, although you never met your grandfather, you are interested in who he was and what his life was like. He moved to the Dominican Republic from China, got married and had ten children. He opened a successful restaurant, but when the tourists no longer passed by his town, the restaurant went bankrupt. I noticed you showing the relationship between your grandfather's life in China and his life in the Dominican Republic. I also noticed how well you described the sacrifices he made by moving. For example, you went into detail about what his father had been, and about the family he left behind. I noticed that you began the story by telling us why it was important to you, and by making us curious about your grandfather. Example Finally, I wondered about the Chinese family he left behind. Did he ever contact them again? Did he miss them? I wondered if you could have told us more about that. Also, why did your grandfather just stay at home after his restaurant went bankrupt. I wondered how he was able to support himself, and why he didn't try to open another restaurant. What was your father's relationship to your grandfather? Does your father have the same curiosity about his Chinese heritage that you do? Thanks for letting me read your story. Your friend, Bob (Peer Reviewer) http://www.tnellen.com/cybereng/example1.html Response and Students’ Models TEACHER IN CONTROL STUDENT IN CONTROL • Instructional purposes dominate • Defers to teacher's authority • Purpose is to do it correctly • Sees writing as "right or wrong"--purpose is follow formulas and directives • Is apprehensive of uncertainty; wants answers, not questions • Imagined or real rhetorical purposes dominate • Finds authority in own ability to make decisions & in resources • Sees writing as decisionmaking; purpose is to do it effectively by reflecting on decisions & making use of resources • Embraces uncertainty as part of writing; asks questions of self, others Response and Students’ Models TEACHER IN CONTROL STUDENT IN CONTROL • Finds little inherent purpose in writing • Discussion of text focuses on text itself, in "past tense," as artifact • Revises little • Finds much intrinsic worth writing--more conscious of being “in” the writing, even if it is practice-oriented rather than learning • Discussion of text moves among textual, ideational, & interpersonal concerns; is both retrospective and projective; text is fluid • Revises much Modes and Methods • • • • • • • • Traditional marginal and/or end commentary “Insert comments” on electronic texts “Track changes” on electronic texts Video (PIP) responses (e.g., iSight) Digitally taped responses; podcasting; YackPack Emailed responses Personal Web site responses Split screen responses But What About Error? The Place of Error in Assessment • If you work from goals to assessment, concern about error can’t be disconnected from other learning goals or outcomes. It needs to be in your goals, in your assignment design, and in your supporting work. • You can choose to emphasize error a lot, a little, or not at all, depending on your learning goals. Some Suggestions • Error has its place and limits; it’s not up front in the writing process. • There are different kinds of errors with different causes: simple slips, oral interference, dialect sources, ESL sources, conceptual sources. Diagnose and respond accordingly. • Start with meaning/effect: it makes more sense than teaching isolated rules. • Recommend a handbook; use support services. Some Suggestions • Put responsibility back on students whenever possible, but offer guidance. • Make simple errors simple. • Go sparingly. It’s easy to reach overload. • Balance response to the whole group with response tailored to individual students. • Encourage students to create a personal log of errors, written in their own terms with examples from their writing. Some Suggestions • First drafts will have more errors than revised drafts. Support revision and editing. • Limit students’ focus to a few manageable problems in each paper. • Balance your concerns about error with your major learning goals--don’t let error dominate your criteria (e.g., “three grammatical errors and you fail”), but in larger projects, do make error count in your assessment. Questions and Discussion