Law

advertisement

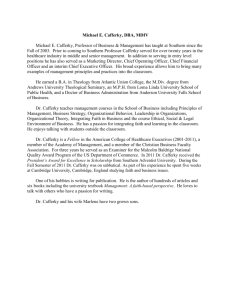

Law ‘Recent Anglo-Australian Developments Affecting Corporations – Corporate Social Responsibility, Contractual Good Faith, and Unconscionable Business Conduct’ By Professor Bryan Horrigan BA, LLB (Hons) (Qld), DPhil (Oxon) Dean, Faculty of Law, Monash University, Australia Author, Corporate Social Responsibility in the 21st Century (2010, Edward Elgar) Overview – Major Themes Comparative, legal, and practical dimensions of three distinct areas of business regulation related to commercial morality: – Corporate social responsibility (CSR) – Good faith in commercial agreements – Unconscionable business conduct Transnational regulatory landscape affecting corporate responsibility and governance Convergence of corporate governance, CSR, and related matters Human rights and business as an integrated aspect of CSR Doctrinal promotion of good faith and fair dealing as aspects of commercial morality: – Express, implied, and excluded good faith obligations – Unconscionable business-to-business and business-to-consumer conduct 2 THE OPERATING ENVIRONMENT FOR CSR AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 3 Living in a Meta-Regulatory World Governance beyond formal government (eg multi-stakeholder networks/alliances/standard-setting mechanisms) Regulation beyond ‘hard’ law (eg ‘soft’ laws, fiscal/policy incentives, pro bono targets, ‘light touch’ regulatory approaches, network-initiated standards etc) Standard-setting beyond national control (eg UN/OECD standards, UK ‘enlightened shareholder value’ approach, international ‘integrated reporting’ initiatives) Responsibility beyond legal compliance (eg corporate social responsibility (CSR), social/reputational risk etc) Success beyond pure profit-internalisation and costexternalisation (eg sustainable business in society) So - multiple, overlapping, cross-sectoral drivers of behaviour and standard-setting for business in society, not limited to the LCD of avoiding breaches of the law 4 Major International Developments Changes in thinking about the basis of corporate law/regulation and corporate governance: – Shareholder primacy v competing policy rationales post-GFC (eg ‘responsible lending’ and ‘responsible investment’ and ‘responsible executive remuneration’) – Command-and-control v relationship-based views of corporate governance – Impact of ‘the third sector’ and the CSR movement Mainstreaming of CSR/CGR&S in business practice - corporate law still lags behind, but is catching up G8 & G20 – CSR a geopolitical policy priority Institutional investment & decision-making standards as investment drivers: – Rise of ESG/SRI considerations – Rise of CR&S-related standards (eg UN PRI) Transnational & international corporate governance & reporting initiatives (eg GRI) UNSRSG mandate (eg business due diligence on human rights) 5 CSR Meta-Trends • From corporate responsibility (CR) to CSR/corporate responsibility and sustainability (eg organisational CR&S policies) • From add-on/marginal element of corporate governance (CG) to integral CG element (eg accountability to stakeholders, management of reputational risk etc) • From financial to non-financial/integrated reporting • From marginal to mainstream ESG/SRI considerations in investment decision-making (eg UN PRI) • From voluntary business CSR commitment to integrated CSR for strategic and competitive advantage (eg Porter and Kramer) • From marginal CSR relevance in orthodox Anglo-American corporate law to CSR prominence in multi-stakeholder coalitions, principle-based regulation, and other metaregulatory influences) • Emerging body of comparative CSR-related law and regulation across European, Anglo-American, and Anglo- 6 Commonwealth jurisdictions Business Reactions to CSR • ‘Every company, like it or not, has a CSR policy. The first issue is whether they recognise the fact, and the second is how far they are alert to changes in what society expects of them in this field.’ (Sir Adrian Cadbury, architect of the UK Cadbury Code on corporate governance) • ‘We’re future-proofing our business model.’ (Unnamed Australian CEO, at a meeting of his company’s corporate responsibility and sustainability working group) • ‘Corporate social responsibility is a very broad agenda. Please give us something we can do differently on Monday morning to make things happen’ (common business reaction, per World Business Council for Sustainable Development) 7 1. Reconceived societal governance, regulation, and responsibility + 2. Orthodox Corporate Governance + 3. 21st century CSR (eg ESG/SRI investment) + 4. Business model integration (ie aligned with strategic business advantage and competitive positioning) = 5. New corporate governance, responsibility, 8 and sustainability (CGR&S) Lagging Behind on CGR&S is Now a More Risky Business Stance – For Companies and Lawyers! • Law firms being audited by business clients on CGR&S factors • Business peers using CGR&S for branding and competitive advantage • CGR&S values and being an ‘employer/provider of choice’ • CGR&S values increasingly part of supply/distribution chain standards • Mass consumer, political, investor, and NGO pressures towards ratcheting-up standards in line with CGR&S values • CGR&S values working their way into corporate legal obligations, including corporate governance and 9 CSR AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 10 CSR’s Links to Corporate Law and Governance • • • • • • • • • • Corporate governance mainstreaming/integration Incorporation and liquidation Corporate capacities and powers Directors’ duties and defences Corporate risk management Corporate reporting and disclosure Shareholder engagement and remedies Non-shareholder engagement and remedies Investment decision-making Corporate law’s service to public policy goals 11 Director Duties - Overview Directors’ duties Loyalty and good faith Duty to act bona fide in the interests of the company Duty to use powers for proper purposes Section 181(1) Duty to act in good faith in best interests of corporation and for proper purposes Duty not to misuse information or position Sections 183, 184 Criminal offences section 184 if reckless or internationally dishonest Duty not to fetter discretions Related party transactions Chapter 2E General law Care, diligence, and skill Duty to avoid actual and potential conflicts of interest Disclosure of and voting on matters of material personal interest Part 2D.1 Div 2 (sections 191-196) Duty to use care and diligence of a reasonable person subject to business judgment rule Section 180(1) and (2) Other sections where Corporations Act requires ‘diligence’ Section 588G Sections 292318 From: Farrar, Corporate Governance Theories, Principles and Practice (OUP 2005) page 104 Directors’ Duties & Non-Shareholder Interests • In Australia – consensus view: – Directors can consider them … – … to the extent relevant to shareholder value – Connection needed between non-shareholder benefit & company’s interests – Business judgment rule offers some extra leeway • In USA: – Delaware – Corporate constituency laws (cf new UK model) • In the UK – new statutory duty of loyalty for directors: – Overall duty to promote success of company for its members – Directors must consider designated stakeholder interests (eg employees, essential business relationships (eg suppliers), reputation for high business standards, impact on environment and communities, long-term consequences of decisions etc) – Possible breach of other directors’ duties (eg care & diligence) if not done properly – Very limited scope for remedies against directors for inadequate consideration of stakeholder interests New UK Directors’ Duty 172 Duty to promote the success of the company (1) A director of a company must act in the way he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, and in doing so have regard (amongst other matters) to– (a) the likely consequences of any decision in the long term, (b) the interests of the company´s employees, (c) the need to foster the company´s business relationships with suppliers, customers and others, (d) the impact of the company´s operations on the community and the environment, (e) the desirability of the company maintaining a reputation for high standards of business conduct, and (f) the need to act fairly as between members of the company. (2) Where or to the extent that the purposes of the company consist of or include purposes other than the benefit of its members, subsection (1) has effect as if the reference to promoting the success of the company for the benefit of its members were to achieving those purposes. (3) The duty imposed by this section has effect subject to any enactment or rule of law requiring directors, in certain circumstances, to consider or act in the interests of creditors of the company. • • 417 Contents of directors' report: business review (2) The purpose of the business review is to inform members of the company and help them assess how the directors have performed their duty under section 172 (duty to promote the success of the company). • (5) In the case of a quoted company the business review must, to the extent necessary for an understanding of the development, performance or position of the company´s business, include– (a) the main trends and factors likely to affect the future development, performance and position of the company´s business; and (b) information about– (i) environmental matters (including the impact of the company´s business on the environment), (ii) the company´s employees, and (iii) social and community issues, including information about any policies of the company in relation to those matters and the effectiveness of those policies; and (c) subject to subsection (11), information about persons with whom the company has contractual or other arrangements which are essential to the business of the company. If the review does not contain information of each kind mentioned in paragraphs (b)(i), (ii) and (iii) and (c), it must state which of those kinds of information it does not contain. • • • • • • • • • • • • (6) The review must, to the extent necessary for an understanding of the development, performance or position of the company´s business, include– (a) analysis using financial key performance indicators, and (b) where appropriate, analysis using other key performance indicators, including information relating to environmental matters and employee matters. "Key performance indicators" means factors by reference to which the development, performance or position of the company´s business can be measured effectively. What Directors Must Do & Report Under New UK Business Review – Purpose: to inform members (not stakeholders) & help them assess how well directors perform duties (note cross-relation to duties) – To the extent necessary to understand the company’s business position, listed companies must comment on: • Main trends/factors likely to affect future of the company’s business • Information about company’s environmental impact, employees, and relevant social and community issues (including information about policies on these and the policies’ effectiveness) • Information about company supply chain relationships (subject to confidentiality & legal constraints) – Must state explicitly if none of this information appears – Must also include both financial and non-financial performance data (eg KPIs related to environmental & employee matters) – Important exemptions: • small companies exempted from business review altogether • medium-sized companies exempted from non-financial information ASX CGC PROPOSALS IN CONTEXT 17 Relevant Principles and Recommendations • ‘Principle 3 – Promote ethical and responsible decision-making’ • ‘Principle 7 – Recognise and manage risk’: – Revised Recommendation 7.1: move from having and disclosing risk management policies to establishing stand-alone risk committee or combined audit/risk committee – Q: what is a ‘material business risk’ in the new era of integrated financial/non-financial reporting? 18 New Recommendation • ‘Recommendation 7.4: A listed entity should disclose whether, and if so how, it has regard to economic, environmental and social sustainability risks.’ • Recognises enhanced global investment attention to ESG factors • Impact of the volume of capital now under UN PRI expectations of ESG disclosures • Domino effect of comparable developments in UK, HK, Singapore etc • Premature to mandate integrated reporting until international framework established 19 Eg Investment Product Disclosure • Investment products include investments in share, super, etc funds • Investment product disclosure statement must contain: – ‘if the product has an investment component – the extent to which labour standards or environmental, social or ethical considerations are taken into account in the selection, retention or realisation of the investment’ (Corporations Act s1013D(1)(l)) 20 UN Principles for Responsible Investment • ‘We will incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes. Possible actions: • – – – – – – – Address ESG issues in investment policy statements Support development of ESG-related tools, metrics, and analyses Assess the capabilities of internal investment managers to incorporate ESG issues Assess the capabilities of external investment managers to incorporate ESG issues Ask investment service providers (such as financial analysts, consultants, brokers, research firms, or rating companies) to integrate ESG factors into evolving research and analysis Encourage academic and other research on this theme Advocate ESG training for investment professionals’ 21 Freshfields Advice for UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative • Question: ‘Is the integration of environmental, social and governance issues into investment policy (including asset allocation, portfolio construction and stock–picking or bond–picking) voluntarily permitted, legally required or hampered by law and regulation; primarily as regards public and private pension funds, secondarily as regards insurance company reserves and mutual funds?’. 22 Freshfields Answers • Countries: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, UK, US, Canada, Australia • ‘(D)ecision-makers are required to have regard (at some level) to ESG considerations in every decision they make….because there is a body of creditable evidence demonstrating that such considerations often have a role to play in the proper analysis of investment value’ • ‘(I)ntegrating ESG considerations into an investment analysis so as to more reliably predict financial performance is clearly permissible and is arguably required in all jurisdictions’ 23 HOW HUMAN RIGHTS RELATE TO CSR, ESG, AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 24 21st Century Business & Human Rights Milestones • Draft UN Norms on the Responsibilities of TNCs and Other Business Enterprises with regard to Human Rights (early 21st century) • Initial UNSRSG appointment (mid-decade) – Harvard’s Prof John Ruggie • ‘Protect, respect, and remedy’ FRAMEWORK (2008-2009): – ‘the state duty to protect against human rights abuses by business’ – ‘the corporate responsibility to respect human rights’ – ‘the need for better access by victims to effective remedies’ • Other key initiatives (2009-2010): – Global corporate law tools project – Human rights due diligence by business • GUIDING PRINCIPLES (2011) • Endorsement by UNHRC and flow-through to other major standardsetting norms (eg OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, IFC social/environmental performance standards, Equator Principles III) • Standard-setting application to various arms of the legal profession • Application to latest ASX CGC proposals? 25 • Advice to UNSRSG - Australian Legal Position No general legal duty on Australian companies to respect international human rights • However, there are due diligence processes in meeting general legal obligations that involve human rights consideration: – – – – – – – – corporate compliance with laws with specific human rights elements (eg anti-discrimination, employment, and privacy laws); business impact assessments for project and infrastructure development (eg socio-economic impact studies, EISs, and HRIAs); rights-related preconditions for granting governmental approvals and licences for business infrastructure and development proposals; compliance with directors’ duties and defences (eg adequate consideration of the relation between rights-related stakeholder interests and long-term corporate success); corporate responses to shareholder action including litigation (eg shareholder proposals, institutional investor dialogue, and climate change litigation); satisfaction of ESG and SRI concerns of institutional investors; conformance with investment decision-making requirements (eg ethical, labour, environmental, and human rights considerations in choosing or realizing investments); and corporate governance requirements for corporate responsibility and 26 sustainability reporting (eg reportable human rights risks and business success drivers as ‘material business risks’). Law FEATURES OF THE RUGGIE HUMAN RIGHTS TEMPLATES 27 Crux = Due Diligence • Q: What are the elements of good human rights due diligence?: • A: Companies need: – (a) a human rights policy; – (b) a starting list of rights comprised in the international bill of human rights and the core ILO conventions; – (c) standard use of human rights impact assessments (akin to social impact statements, environmental impact assessments etc); – (d) integration/alignment of human rights due diligence and company’s systems/processes/measures (think CG here!); and – (e) monitoring/verification and internal/external reporting of human rights performance 28 Foundational Principle for Business - Principle 15 ‘15. In order to meet their responsibility to respect human rights, business enterprises should have in place policies and processes appropriate to their size and circumstances, including: (a) A policy commitment to meet their responsibility to respect human rights [#1 Integrated CSR/HR organisational policy]; (b) A human rights due-diligence process to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their impacts on human rights [#2 Integrated HRDD throughout organisation]; (c) Processes to enable the remediation of any adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute. [#3 Integrated monitoring/engagement/reporting mechanisms]’ 29 Law Legal Position in UK, Australia, Hong Kong, and Singapore on Good Faith ‘Fair Dealing and Good Faith’ Opt-in rules for international commercial contracts (UNIDROIT principles) Other norms of international commercial law (eg UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods) Contract law doctrines (eg implied terms of good faith and fair dealing) Business and industry expectations (eg good faith in mining joint ventures, franchises, public sector contracts) Choice of governing law (eg NY contract law, NSW law) in cross-border agreements Common law and equitable doctrines against harsh, unreasonable, exploitative exercises of contractual/legal rights (eg relief against forfeiture) Multiple forms of statutory and non-statutory unconscionable conduct (eg Competition and Consumer Act (Cth) and unconscionable dealings doctrine) National regulation of unfair contract terms Factors affecting exercises of statutory powers and discretions 31 Academic/Judicial Views on Good Faith ‘Good faith is inherent in all common law contract principles, and any attempt to imply an independent term is unnecessary and a retrograde step.’ (Carter, Peden, and Tolhurst) ‘(T)he principle of good faith should be seen not as an implied term, but rather as a principle that governs the implication of terms and [the] construction of contracts generally.’ (Carter and Peden, discussed in Ng Giap Hon v Westcomb Securities [2009] SGCA 19) ‘In our view, there is no good reason why an express agreement between contracting parties that they must negotiate in good faith should not be upheld.’ (HSBC Institutional Trust Services (Singapore) Ltd v Toshin Development Singapore Pte Ltd [2012] SGCA 48) ‘[Good faith is] a concept which means different things to different people in different moods at different times and in different places.’ (North American view, > 25 years ago) ‘The mistrust of Anglo-Saxon jurists for the general concept of good faith is equalled only by the imagination which they put towards multiplying particular concepts which lead to the same result.’ (European view) 32 Ongoing Transnational Controversies Is an obligation to negotiate in good faith enforceable? How pervasive is good faith in the construction of commercial agreements? Can good faith be implied in some or all commercial agreements? Under what conditions is good faith implied into a commercial agreement? Are good faith obligations co-extensive or otherwise interactive with related obligations of contractual cooperation and fidelity? What are the elements and limits of good faith? Can obligations of good faith be modified or excluded by agreement? 33 Landmark Cross-Jurisdictional Case Law Australia: – Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust v South Sydney City Council [2002] HCA 5 – multiple intermediate appellate court decisions from early 1990s to 2012 UK: – Socimer International Bank Ltd v Standard Bank London Ltd [2008] EWCA Civ 116 – Yam Seng Pte Ltd v International Trade Corporation [2013] EWHC 111 (Feb 2013) – Mid Essex Hospital Services NHS Trust v Compass Group UK and Ireland Ltd [2013] EWCA Civ 200 (March 2013) – TSG Building Services v South Anglia Housing [2013] EWHC 1151 (May 2013) Hong Kong: – GDH Ltd v Creditor Co Ltd [2008] 5 HKLRD 895 Singapore: – Ng Giap Hon v Westcomb Securities Pte Ltd [2009] SGCA 19 (implied term) – HSBC Institutional Trust Services (Singapore) Ltd v Toshin Development Singapore Pte Ltd [2012] SGCA 48 (express obligation to negotiate in good faith) 34 Current Australian Legal Position • Mixed results over time on whether good faith is implied in commercial agreements • No general term implied by operation of law that: – parties must act in good faith when negotiating a contract – parties must exercise good faith in performing a contract • Good faith terms can be implied in specific contracts (eg employment contracts, franchising contracts, or if contract otherwise void for uncertainty) • Current academic/judicial debate over: – What good faith means (eg honest disclosure, non-arbitrariness, reasonableness – and what kind of reasonableness?) – Correlation/overlap with cognate obligations (eg cooperation, mutual fidelity) – Whether some notion of good faith underlies all or much contract law doctrine – Whether good faith is an extra term or a rule of construction (ie the method of incorporation) – Whether existing judicial approach of implying good faith terms is correct – What method for implying terms applies in particular circumstances – Limits of good faith obligations in contract (eg legitimate commercial expectations) – Limits to excluding contractual good faith by drafting devices – Relationship between good faith in contract and lack/breach of good faith as an aspect of unconscionable business conduct 35 Law Client-Focused Negotiating Stances and Drafting Approaches on Good Faith Drafting Perspectives on Good Faith ‘(M)y present feeling is that an attempt contractually to exclude the duty to act honestly would fail [and] what foolhardy entity would be prepared to contract on that basis anyway [but] the possibility of contractually excluding an obligation to act reasonably in [the] objective sense is much more arguably open.’ (Australian state supreme court CJ (de Jersey CJ)) ‘Commercial parties are now faced with the question of whether they dare to suggest in negotiations that they are not prepared to perform in ‘good faith’ as that may require reasonableness on their part. Alternatively, should they expressly state that they will not behave reasonably, or will that be a “dealbreaker”?’ (Prof Peden) ‘Whether you characterise the question as one of ‘good faith’ or of the court believing that it has more wisdom than the parties to determine what is reasonable, the practitioner has a problem … A clear clause will embarrass the judiciary into submission.’ (Canadian practitioner, 1985) ‘I find arresting the suggestion that an “entire agreement” clause is of itself sufficient to constitute an express exclusion of an implied duty of good faith and fair dealing.’ (Prominent Australian academic/judge (Paul Finn), 2003) 37 Client-Focused Analysis of GF Options #1: Relevant industry standard/expectation? (eg mining JVs, franchising) #2: Relevant client preference/need? (eg public v private sector contexts) #3: Effective combination of clauses for exclusion, eg: – – – – – ‘entire agreement’ clause ‘sole discretion’ clause ‘negation of implied terms’/exclusion clause (ie not just GF?) ‘no other/additional obligations’ clause (ie to cover things beyond implied terms) ‘no other dilution of our client’s position by operation of law, to the extent it can be excluded’ clause (ie to maximise exclusionary effect) – flow-on effect of mixed express/silent treatment of GF throughout agreement #4: Other means/doctrines that condition exercise of contractual rights and surrounding conduct – unfair, arbitrary, unreasonable, and unconscientious exercises of powers and discretions #5: Supervening regulation by law regardless of parties’ private agreement: – limiting doctrines (eg limits on exclusion clauses) – legislative intrusion (eg ‘unfair contract terms’ and ‘unconscionable conduct’ laws) – other regulation (eg codes of conduct) 38 Multi-Level Drafting Options on GF Use ‘choice of governing law’ clause as default GF position: – cross-border transactions (eg law of NY) – Australian jurisdiction (eg NSW v Victoria) Remain silent – leave it to the courts to imply down the track Impose express, general, and undefined GF obligation on some/all parties Impose express, general, and defined GF obligation on parties Define/confine GF throughout the contract: – Only some parties in some contexts – Only for some stages of the contract Exclude GF to the extent lawfully possible 39 Corporate, Finance, Resource, Infrastructure Precedents Common contexts for express good faith elements (especially when in both parties’ interests and therefore binds both): – Disclose in good faith – Negotiate in good faith – Take all actions in good faith and with due diligence – Certifying/warranting in good faith – Transfer/purchase/valuation options – Use of information – Standard law firm precedents using/raising good faith issues: – Business/share sale agreements – Schemes of arrangement – Mining JV – Finance and security agreements – Project/construction agreements – Public sector contracts 40 Drafting Examples – Express Good Faith (Qld Case) ‘The parties warrant that they shall perform all duties and act in good faith. Acting in good faith includes: (a) being fair, reasonable, and honest; (b) doing all things reasonably expected by the other party and by the Subcontract; and (c) not impeding or restricting the other party’s performance.’ 41 Drafting Examples - Vodafone Case Clauses 24.1 Exclusion of Warranties and representations (a) (Exclusion) To the full extent permitted by Law and other than as expressly set out in this Agreement the parties exclude all implied terms, conditions and warranties. (b) ….. (c) (MI has made own inquires) MI acknowledges and declares to Vodafone that, in making its decision to become Vodafone Billing Services' non-exclusive agent service provider on the terms of this Agreement, it has carried out all feasibility studies, inquiries, investigations and due diligence exercises that it considers necessary and prudent, and it has consulted its own independent professional consultants (including accountants and legal advisors) on such matters as the terms of this Agreement and the profitability and viability of performance under this Agreement. 42 Drafting Examples - Vodafone Case Clauses 44. Entire Agreement This agreement contains the entire agreement of the parties with respect to its subject matter. It sets out the only conduct relied on by the parties and supersedes all earlier conduct by the parties with respect to its subject matter. 43 Ng Giap Hon v Westcomb Securities [2009] SGCA 19 ‘Entire Understanding This Agreement embodies the entire understanding of the parties and there are no provisions, terms, conditions or obligations, oral or written, expressed or implied, other than those contained herein. All obligations of the parties to each other under previous agreements ([if] any) are hereby released, but without prejudice to any rights which have already accrued to either party.’ 44 Law Good Faith as an Indicator in Statutory Regulation of Unconscionable Business Conduct in both B2B and B2C Transactions ‘Hot’ Industry Areas for UC/GF Regulation Loan and security arrangements Financial services and advice Share dealings and investments Franchising Commercial leasing Building and construction Telecommunications Termination/default contexts (all areas) ACCC Chairman Rod Sims (Feb 2012): ‘Unconscionable conduct between businesses is another area of attention this year and one of particular concern to small business ... Proving UC is, of course, a high hurdle, but where it occurs the ACCC will not hesitate in taking action.’ 46 Unconscionable Conduct Relates to … Various equitable causes of action and bases for relief Statutory unconscionability under Competition and Consumer Act Statutory unconscionability in financial services under ASIC Act Unconscionable financial services licensee conduct under Corporations Act (s991A) Unjust contracts laws (eg NSW Contracts Review Act) Industry codes (eg Banking/Franchising Codes) State retail/commercial leasing laws 47 Three Basic Forms of Statutory Unconscionability General prohibition - unconscionable conduct: - Old TPA s 51AA (in trade practices generally) New CCA ACL, section 20 ASICA s 12CA (in financial services) Corporations Act s 991A (financial services licensees) Unconscionable conduct in retail/personal/consumer contexts (ie B2C unconscionability): - Old TPA s 51AB New CCA ACL, sections 21 and 22 ASICA sections 12CB and 12CC Unconscionable conduct in big/small business contexts (ie B2B unconscionability): - Old TPA s 51AC New CCA ACL, sections 21 and 22 - ASICA sections 12CB and 12CC - Some state commercial/retail leasing Acts 48 ACCC v Lux Distributors P/L [2013] FCAFC 90 (15 August 2013) Latest ACCC test case B2C context, not B2B Facts predate the latest statutory unconscionability reforms Old (not harmonised) list of unconscionability indicators (eg no ‘good faith’ indicator) No mention of latest additions (eg new principles of interpretation) in the judgment Judicial rethink on how ‘moral obloquy’ works in this field of regulation Very far from being the last word on statutory unconscionability 49 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (As of 6 June 2012) 20 Unconscionable conduct within the meaning of the unwritten law (1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is unconscionable, within the meaning of the unwritten law from time to time. 50 Strands of Unconscionable Dealing • AMADIO-Type UC • Weaker party under a special Wife (or other close disadvantage relationship?) • Special disadvantage can be personal (eg illiteracy) Guarantees husband’s • Special disadvantage can also be personal/business debts financial, legal, or informational (ie Failure to understand ‘situational’) • Disadvantage affects weaker A volunteer (no benefit) party’s capacity to decide best No or inadequate explanation interests Relevant factors known to bank • Stronger party knows and takes advantage of that disadvantage Bank remedial actions • Exploitation of that disadvantage inadequate in the circumstances is against ‘good conscience’ in legal terms GARCIA-Type UC 51 Meanings & Levels of Unconscionability Regulation Under ‘the Unwritten Law’ (4 categories as described by Paul Finn): – [1] Unconscionability as the underlying concept for Equity as a whole – [2] Unconscionability as an element or finding that is essential for specific equitable actions (eg estoppel, relief against forfeiture, unconscionable dealings, unilateral mistake etc) - Coercion/exploitation/advantage-taking Unconscionable exercise of rights, retention of benefits etc – [3] Doctrines & remedies associated with unconscionable dealings & exploitation, advantage-taking, and defective understanding: – – – ‘spousal guarantees’ rules (eg Yerkey v Jones, Garcia) ‘special disadvantage’ rule (eg Amadio/Berbatis) Others (eg Bridgewater v Leahy) – [4] Unconscionability as a direct ground of relief in its own right, unmediated by conventional doctrines (eg Lenah Game Meats v ABC) • NB Only [2] or [3] are viable possibilities – still open to argument 52 Full Fed Ct in ACCC v Samton Holdings Unconscientious exploitation of a party’s special disadvantage (eg Amadio) Defective understanding, relationship of influence, and absence of independent explanation (eg Garcia) Unconscionable departure from previous representation (eg estoppel – Verwayen, Waltons Stores v Maher) Relief against forfeiture and penalty (eg Legione v Hateley and Stern v McArthur) Rescind contracts for unilateral mistake (eg Taylor v Johnson) 53 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) 21 Unconscionable conduct in connection with goods or services (1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with: (a) the supply or possible supply of goods or services to a person (other than a listed public company); or (b) the acquisition or possible acquisition of goods or services from a person (other than a listed public company); engage in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable. Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) 21 Unconscionable conduct in connection with goods or services (4) It is the intention of the Parliament that: (a) this section is not limited by the unwritten law relating to unconscionable conduct; and (b) this section is capable of applying to a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, whether or not a particular individual is identified as having been disadvantaged by the conduct or behaviour; and (c) in considering whether conduct to which a contract relates is unconscionable, a court’s consideration of the contract may include consideration of: (i) the terms of the contract; and (ii) the manner in which and the extent to which the contract is carried out; and is not limited to consideration of the circumstances relating to formation of the contract. 55 Spigelman CJ in A-G (NSW) v World Best Holdings [2005] NSWCA 261 ‘Over recent decades legislatures have authorised courts to rearrange the legal rights of persons on the basis of vague general standards which are clearly capable of misuse unless their application is carefully confined. Unconscionability is such a standard … Unconscionability is a concept which requires a high level of moral obloquy. If it were to be applied as if it were equivalent to what is “fair” or “just”, it could transform commercial relationships.’ 56 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 1974 No. 51 (Cth) (As of 6 June 2012) (Annotations in ‘[ ]’) 22 Matters the court may have regard to for the purposes of section 21 [Non-Exhaustive List of 12 Statutory Indicators of B2C and B2B UC]: (a) [relative bargaining positions] the relative strengths of the bargaining positions of the supplier and the customer; and (b) [beyond legitimate commercial interests] whether, as a result of conduct engaged in by the supplier, the customer was required to comply with conditions that were not reasonably necessary for the protection of the legitimate interests of the supplier; and (c) [understanding of documents] whether the customer was able to understand any documents relating to the supply or possible supply of the goods or services; and 57 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 1974 No. 51 (Cth) (As of 6 June 2012) (d) [undue influence, unfair tactics, and duress] whether any undue influence or pressure was exerted on, or any unfair tactics were used against, the customer or a person acting on behalf of the customer by the supplier or a person acting on behalf of the supplier in relation to the supply or possible supply of the goods or services; and (e) [equivalent pricing and circumstances] the amount for which, and the circumstances under which, the customer could have acquired identical or equivalent goods or services from a person other than the supplier; and (f) [equivalent treatment] the extent to which the supplier’s conduct towards the customer was consistent with the supplier’s conduct in similar transactions between the supplier and other like customers; and (g) [code compliance I] the requirements of any applicable industry code; and 58 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 1974 No. 51 (Cth) (As of 6 June 2012) (h) [code compliance II] the requirements of any other industry code, if the customer acted on the reasonable belief that the supplier would comply with that code; and (i) [non-disclosure] the extent to which the supplier unreasonably failed to disclose to the customer: (i) any intended conduct of the supplier that might affect the interests of the customer; and (ii) any risks to the customer arising from the supplier’s intended conduct (being risks that the supplier should have foreseen would not be apparent to the customer); and 59 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 1974 No. 51 (Cth) (As of 6 June 2012) (j) [contractual terms, progress, and conduct] if there is a contract between the supplier and the customer for the supply of the goods or services: (i) the extent to which the supplier was willing to negotiate the terms and conditions of the contract with the customer; and (ii) the terms and conditions of the contract; and (iii) the conduct of the supplier and the customer in complying with the terms and conditions of the contract; and (iv) any conduct that the supplier or the customer engaged in, in connection with their commercial relationship, after they entered into the contract; and (k) [unilateral variation] without limiting paragraph (j), whether the supplier has a contractual right to vary unilaterally a term or condition of a contract between the supplier and the customer for the supply of the goods or services; and (l) [good faith] the extent to which the supplier and the customer acted in good faith. 60