File - Apex

advertisement

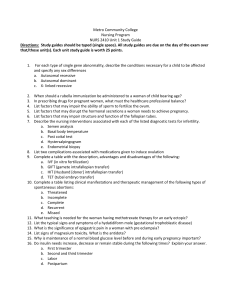

Exercise and Pregnancy A Fitness Guide To: Keeping in Shape for a Safe and Healthy Delivery, and a Quick Recovery. Alex Tieri • • • • Certified Medical Exercise Specialist Orthopedic Exercise Specialist Performance Enhancement Specialist Advanced Health and Fitness Specialist – American Council on Exercise – Highest certification, 1 of 1000 in U.S. (7/2012) – Specializing in: • • • • • • • Pre- and Postnatal Exercise CVD, CAD, CHD Hypertension and Dyslipidemia, Diabetes and The Metabolic Syndrome Asthma Arthritis and Osteoporosis Elderly Optimal Living • Nutritional Consultant (AFPA) To Be Discussed: • Benefits and Risks of exercise during pregnancy. • Physiological changes during pregnancy • Programming guidelines and considerations for prenatal exercise • Biomechanical considerations for the pregnant mother • Nutritional considerations • Psychological considerations • Benefits and risks following pregnancy • Programming guidelines and considerations following pregnancy Introduction • There is a growing trend of women who are not physically active to view pregnancy as a time to modify their lifestyles to include more health conscious decisions, including exercise. • Aerobic and strength training during pregnancy, have shown no increase in early pregnancy loss, late pregnancy complications, abnormal fetal growth, or adverse neonatal outcomes, suggesting previous recommendations have been overly conservative (Clapp, 1989; O’Neil, 1996). Benefits and Risks During Pregnancy • Regular exercise is associated with lower incidence of excessive maternal weight gain, gestational diabetes(GDM), pregnancy induced hypertension, varicose veins, deep vein thrombosis, dyspnea, and low-back pain (Davies et al.,2003; Weissgerber et al.,2006) • Women who continue regular weight bearing exercise throughout the entire pregnancy tend to have easier, shorter and less complicated deliveries (Clapp, 2002). • Pregnant exercisers had average weight increases of 29 lbs well within normal range, and a body fat mass 3% lower than pregnant non-exercisers (Clapp & Little, 1995). Gestational Diabetes(GDM) • Is when glucose intolerance is first recognized during pregnancy. • Maternal muscular insulin resistance is normal during midpregnancy, to ensure adequate glucose regulation for fetal growth and development. • Women with GDM the insulin increase is exacerbated, resulting in maternal hyperglycemia, resulting in complications in labor and delivery, as well as Caesarean section. • Risk factors include: Hispanic, Asian, African Descent; age >35; overweight BMI >25; obese BMI >30; or a history of insulin resistance. • Participation in recreational activities within the first 20 weeks of gestation decreases risk of GDM by almost 50% (Dempsey et al., 2004) • GDM is treated primarily through nutritional management by a registered dietician, and exercise. Preeclampsia • • • • • • Is usually diagnosed 20 weeks after pregnancy is characterized by persistent hypertension (140/90 mmHg) and proteinuria >0.3g (ACOG, 2002a). Associated complications: preterm birth, abruptio placentae, renal failure, pulmonary edema, cerebral hemorrhage, circulatory collapse, eclampsia, and immediate delivery. Associated risk factors: abnormal placental development, predisposing maternal constitutional factors, oxidative stress, immune maladaptation, and genetic susceptibility. Regular leisure-time physical activity in early pregnancy is associated with a reduced incidence of preeclamsia (Weissgerber et al., 2004) Several protective mechanisms from exercise are thought to play a role in preeclampsia prevention, including enhanced placental growth and vascularity, enhanced antioxidant defense systems, reduction of the systematic inflammatory response, and improved endothelial function (Weissgerber et al., 2006). Ambulatory management is the norm with treatment for preeclampsia, while exercise intervention is unclear of positive affects, exercise should be physician monitored. Maternal Obesity • In the U.S. the percentage of women aged 20-39, who are overweight has climbed to 49% amongst white women and 70% among African-American women (Okosun et al., 2004). • Ovulatory infertility increases progressively with increasing BMI, as so the risks of polycystic ovarian syndrome and menstrual irregularities. • In a study of two year infertile obese women losing between 10-22 lbs, 77% were able to conceive (Clark et al., 1998) • Authors hypothesized improved fertility resulted from reduced insulin resistance and lower insulin concentrations on reproductive hormone profiles. • Risk of fetal complications, preeclampsia, GDM, large-forgestational-age infants requiring C-section increase with degree of overweight and obesity (Rooney & Schauberger, 2002). Exercise and Fetal Response • In uncomplicated pregnancies fetal injury is highly unlikely, and most potential risks are hypothetical , such as these: • Selective redistribution of blood flow away from the fetus during prolonged exercise may interfere with the transplacental transport of O2, Co2, and nutrients. – Aquatic exercise has a smaller decrease in plasma volume compared to land exercises, and hydrostatic pressure maintains blood flow around the central organs. • Transient hypoxia could result in fetal tachycardia and an increase in fetal blood pressure, as a protective mechanism to help transfer O2 and decrease Co2 across the placenta. – There are no reports to link these adverse events with maternal exercise, most studies show a minimal to moderate increase in fetal heart rate by 1030bpm (Wolfe et al., 1988). • Intrauterine growth restriction due to strenuous physical activity, has been shown to occur with inefficient nutrition, resulting in low-birthweight. – Overall, it appears that birth weight is not effected by exercise in women with sufficient energy intake (Ahlborg Bodin & Hogsteadt, 1990). Contraindications and Risk Factors • Women with or without a previously sedentary lifestyle should be encouraged to exercise. However, women with a complicated pregnancy should be discouraged from exercise for fear of impacting an underlying disorder (ACSM, 2006;ACOG, 2002b; SOGC & CSEP, 2003). • most physical activities are safe throughout pregnancy. However, overly vigorous activity in the 3rd trimester, activities with a high risk of falling, altitude >6000 ft, and scuba diving should be avoided. Continued: • Absolute contraindications: • Relative contraindications: – Hemodynamically significant heart disease – Restrictive lung disease – Incompetent cervix/Cerclage – Multiple gestation at risk for premature labor – Persistent 2nd or 3rd trimester bleeding – Placenta previa after the 26th week – Premature labor during current pregnancy – Ruptured membranes – Preeclampsia – – – – – – – – – – – – Severe anemia Unevaluated arrhythmia Chronic bronchitis Poorly controlled T1Diabetes Extreme morbid obesity Extreme underweight BMI<12 Extremely sedentary lifestyle Intrauterine growth restriction in current pregnancy Poorly controlled hypertension Orthopedic limitations Poorly controlled hyperthyroidism Heavy smoker Cease exercise and seek medical help • • • • • • • • • • • • • Bloody discharge from vagina Gush of fluid from vagina(ruptured membranes) Sudden swelling(possible preeclampsia) Persistent/ severe headaches or visual disturbances(hypertension) Spell of faintness or dizziness Swelling, pain, and redness in one calf(phlebitis) Elevation of HR or BP persisting after exercise Excessive fatigue, palpitations, or chest pain Persistent contractions >6-8 hr Unexplained abdominal pain Insufficient weight gain <2.2lbs month Decreased fetal movement Amniotic fluid leakage Physiological Changes During Pregnancy • Musculoskeletal – average weight gains of 25-40 lbs(15-25% pre-natal weight), significantly increases forces across joints, causing discomfort to normal, arthritic, and unstable joints. – Mechanical stress of the back, pelvis, hips, and legs increase as COG moves up and outward, sometimes resulting in low-back pain. – During the 1st trimester hormones relaxin and progesterone are released to expand the uterine cavity, by increasing joint laxity, which could possibly cause strains in other ligaments. • Cardiovascular – hormones initiate reduced responsiveness and relaxation in smooth muscle cells of blood vessels, causing many early unpleasant symptoms, and a vascular under fill. To compensate hormones tell the kidneys retain salt and water to increase blood volume. – By mid pregnancy, cardiac outputs are increased 30-50%, and resting HR can be up by 15bpm greater than before pregnancy(Morton, 1991). – Motionless standing, and laying in a supine position can cause a significant decrease in cardiac output, and should be avoided. Continued: • Respiratory – at rest, an increase in the depth of each breath increases the amount of air inhaled by up to 50% (Artal et al., 1986). – Progesterone increases the brain’s sensitivity to Co2, stimulating over-breathing, improving the efficiency of O2 uptake from the lungs and eliminating Co2. – 10-20% improvement to baseline O2 consumption, creates a training effect that can be carried over after birth(Pivarnik et al., 1992). • Thermoregulatory – ability to dissipate heat improves during pregnancy, due to a decrease of the body’s set point in normal temp, increased blood flow to the skin(convection), and a 40-50% increase in tidal volume creates a 40-50% increase in heat loss through exhalation. Exercise Considerations • Avoid activities prolonged motionless standing, laying in the supine position, activities with falling risks, and activities that put repetitive excessive stress on the joints until cleared by physician. • Pregnancy requires an additional 300 cals daily and whatever cals may be lost through exercise. • During the 3rd trimester, increase carbs 30-50g/day to prevent hypoglycemia during exercise. • Wear appropriate clothing and hydrate to prevent hyperthermia. • Use low weights with high reps. • Limit excessive stretching due to joint laxity from hormones • Use the Borg scale of RPE 1-10, between “fairly light” to “somewhat hard” since heart rate is hormonally elevated. • Previously sedentary women should begin with 15 min of continuous exercise 3x per week, and gradually increase it to 30 min 4x per week. Biomechanical Considerations • Low-back pain(LBP) happens as the abdominal muscles are stretched, and lose their ability to help maintain a neutral spine position. Joint laxity in the lumbar spine weakens the ability of static support muscles to withstand the shearing forces bringing pain in the facet joints. – Exercises to help: ROM and stretching of the back extensors, hip flexors, scapulae protractors, internal shoulder rotators, and neck flexors; strengthen: abdominals, gluteals, and scapulae retractors. • Posterior pelvic pain is 4x more prevalent than LBP. It is thought to occur as the sacroiliac(SI) joint dysfunctions from decreased stability of the pelvic girdle, pain can be brought on from prolonged sitting and leaning forward, or standing and leaning forward. – Exercises to help: muscles that act to stabilize the SI joint such as internal and external obliques, lats, erector spinae, multifidus, and gluteus maximus (Vleeming et al., 1996). Continued • Pubic pain is caused by increased motion at the joint called symphysitis, resulting in pain in the pubic region, groin, and medial aspects of the thigh, during weightbearing activities that usually involve lifting one leg, may be accompanied by a grinding or clicking sound of the joint. This may result in a waddling walk. – Treatment is usually to avoid weight bearing activities that aggravate the joint, and a pelvic belt to limit motion of the symphysis may be prescribed. • Carpal tunnel syndrome is compression of median nerve that causes pain and tingling in the thumb, index, and middle fingers, from swelling of repetitive work or movements of the wrist, and possibly excess water retention. Usually goes away after pregnancy. – Avoid loading in hyperextension, grasping objects tightly, repetitive flexion and extension of the wrist during exercise, try to maintain a neutral grip, with a wider circumference. Continued • Diastasis recti is a partial or complete separation between the left and right sides of the rectus abdominal muscle, during the later stages of pregnancy the uterus can be seen bulging out of the abdominal wall. Testing can be done by placing two fingers between the abdominal muscles during a curl-up, an indicator is if the gap is wider than two fingers. This can remain after pregnancy. – Treatment: abdominal compression exercises and curl-ups in a semi recumbent position. • Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is an involuntary loss of urine from a rise in abdominal pressure. During pregnancy and labor prolonged stretching of the pelvic floor muscles, and neural muscular damage, interfere with normal transmission of information regarding changes to abdominal pressure to proximal urethra. This can last after pregnancy. – Treatment: Kegel exercises provide support to the pelvic organs; preventing a falling of the bladder, uterus, and rectum; supporting proper pelvic alignment; sphincter control; enhances circulation of the pelvic floor muscles; and provides a healthy environment after labor (Dunbar, 1992). Nutritional Considerations • After the thirteenth week of pregnancy an additional 300 calories is needed to maintain homeostasis, and an additional for calories used during exercise. • Pregnant women should consume between 2500-2700 calories per day. • Increasing carbohydrates is especially important as pregnant women use more at rest and exercise (Artal & Wiswell, 1996). • To avoid hypoglycemia small meals and snacks should be eaten throughout the day especially before and after exercise. • Women considering getting pregnant should consume adequate: folic acid, iron, calcium, vitamin D, and water to sustain health before, during, and after pregnancy. • Normal weight women should gain 25-35 lbs; underweight women should gain 28-40 lbs; overweight women should gain 15-25 lbs; and obese women should gain at least 15 lbs. Psychological Considerations • Pregnancy is associated with increased psychological stress for many women, which includes increased anxiety, depression, and fatigue. • Depression is more common during the third trimester. • 97% of women report fatigue as a concern during some point of the pregnancy. • Studies have shown that babies of anxious or stressed mothers have low birth weight and tend to be delivered early (Evans et al, 2001). • Ultrasound studies have shown that fetal behavior is affected by maternal anxiety (Groome et al., 1995). • Blood flow to the baby may be impaired through the uterine arteries with high levels of maternal anxiety (Teixeira, fisk, & Glover, 1999). • Postpartum depression affects 10-13% of women lasting 2-6 months after delivery, with greater chances of depression in the future (Cooper & Murray, 1995). • Maternity blues refers to the tearfulness, irritability, hypochondriasis, sleeplessness, impairment of concentration and a headache, that usually peaks the 4th or 5th day postpartum, from the raising of hormones prolactin, and falling levels of progesterone, estradiol, and cortisol (Harris et al., 1994). • In a study that measured physical activity and mood during pregnancy, healthy women who maintained physical activity during pregnancy enjoyed more mood stability (Poudevigne & O’Connor, 2005). Benefits and Risks of Exercise Following Pregnancy • Preventing obesity and weight gain through promotion of body fat/weight loss. • Promoting aerobic fitness and strength, leading to an improved ability to perform the acts of mothering. • Optimizing bone health by increasing bone mineral density and preventing lactation associated bone loss, from estrogen deficit. – Lactation drains calcium by an additional 200-400mg per day. • Improving mood, self-esteem, and energy. – Acute bout of exercise has been shown to lead to decreases in acute transitory anxiety and depression as well as increases in vigor (Kotlyn & Schultes, 1997). • A study of postnatal exercise breast milk revealed no remarkable difference as far as nutrient loss, and lactic acid between women who performed submaximal, maximal, and no exercise (Larson-Meyer, 2002). • c-section under goers usually report pain and tenderness in the abdomen as well as considerable fatigue. Rehabilitation is walking as soon as possible to prevent muscle wasting, increase circulation, and speed the healing process. Deep breathing, kegels, and abdominal compression exercises can be done early in the recovery process. – Structured fitness programs should be withheld until physician clearance usually around the six-week postpartum check-up. Physiological Changes Postpartum • The hormone relaxin elevates 10x its normal level during pregnancy, which promotes laxity in ligaments for growth, this can lead to overstretching and strains, and can last up to 8 months postpartum. • Cardiac output increases as much 40% and plasma volume can increase 40-50% during pregnancy, levels will return to normal within 6-8 weeks of delivery. • Minute ventilations can increase by 50%, along with increases in tidal volume, and respiratory rate, values return to normal 6-12 weeks postpartum. • There are no known maternal complications associated with the resumption of exercise training postpartum (Hale & Milne, 1996). Postnatal Exercise Programming • • • • • Begin slowly increase gradually. Avoid excessive fatigue and dehydration. Support and compress the abdomen and breasts. Stop and evaluate with pain. Seek medical evaluation with bleeding heavier than a period. • 1st year goal is to improve physical fitness. • Work the core, and deep pelvic muscles. • Increased breast weight from lactation, postures associated with cuddling, holding, and feeding may lead to upper back pain. – Stretch anterior shoulder girdle, follow with scapular retraction and external shoulder rotation exercises, to improve posture and ease pain with these biomechanical concerns.