IUN-nodalida

advertisement

Issues Under Negotiation

Staffan Larsson

Dept. of linguistics, Göteborg University

sl@ling.gu.se

NoDaLiDa, May 2001

Overview

• background

• Sidner: a formal account of

negotiative dialogue

• problems with Sidner’s account

• an alternative account based on

Issues Under Negotiation

• example

• summary

Background

• TRINDI project

– TrindiKit: a toolkit for building and

experimenting with dialogue systems

– the information state approach

– GoDiS: an experimental dialogue system

simple information-seeking dialogue

• SIRIDUS project

– extend GoDiS to handle action-oriented

dialogue and negotiative dialogue

The information state

approach – key concepts

• Information states represent information

available to dialogue participants, at any given

stage of the dialogue

• Dialogue moves trigger information state

updates, formalised as information state

update rules

• Update rules consist of conditions and

operations on the information state

• Dialogue move engine updates the information

state based on observed moves, and decides

on next move(s)

GoDiS features

• information-seeking dialogue

• Information state based Ginzburg’s notion of

Questions Under Discussion (QUD)

• Dialogue plans to drive dialogue

• Simpler than general reasoning and planning

• More versatile than frame-filling and finite

automata

• Has been extended to handle instructional

dialogue

• Also being extended to handle negotiative

dialogue (SIRIDUS)

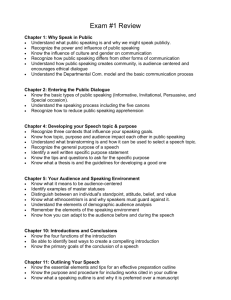

control

DME

input

interpret

update

select

generate

output

Information State

database

lexicon

domain

knowledge

Sample GoDiS information state

AGENDA =

PRIVATE =

PLAN =

{ findout(?return) }

findout(?x.month(x))

findout(?x.class(x))

respond(?x.price(x))

BEL = { }

TMP = (same structure as SHARED)

SHARED =

dest(paris)

COM =

transport(plane)

task(get_price_info)

QUD = < x.origin(x) >

LM = { ask(sys, x.origin(x)) }

Problem with current

GoDiS

• can only represent information about

one flight at a time

• but we want to be able to

– talk about several flights,

– allowing the user to ask questions about

them,

– deciding on one of them, and then

– getting price information / booking a flight

• Requires negotiation

Sidner: an artificial

language for negotiation

• formal account of negotiative

dialogue

• “state of communication”

– beliefs (individual)

– intentions

– mutual beliefs

– stack of open beliefs (OpenStack)

– stack of rejected beliefs

Sidner cont’d

• agents transmit messages with

propositional contents

– ProposeForAccept(PFA agt1 belief agt2)

• agt1 expresses belief to agt2, intending agt2

to accept belief

• belief is pushed on OpenStack

– Reject (RJ agt1 belief agt2)

• agt1 does not believe belief

• belief is popped from OpenStack and pushed on

RejectedStack

– Accept (AP agt1 belief agt2)

• agt1 and agt2 now hold belief as a mutual

belief

• belief is popped from OpenStack

Sidner: counterproposals

• Counter (CO agt1 belief1 agt2 belief2):

without rejecting belief1, agt1 offers

belief2 to agt2

• analysed as two proposals

– (PFA agt1 belief2 agt2)

– (PFA agt1 (Supports belief2 (Not belief1))

• A counterproposal requires that the new

proposal conflicts with a previous proposal

• In this way, Sidner can distinguish unrelated

proposals from related proposals

A problem with

counterproposals

• problems:

– proposals of alternative solutions to same

problem are seen as counterproposals, i.e.

as conflicting with previous proposals

• but often alternative proposals do not conflict

with previous proposals (e.g. buying a CD)

– a proposal commits an agent to intending

that the addressee accepts the

counterproposal rather than previous

proposals,

• but e.g. a travel agent is usually quite indifferent

to which proposal is accepted

Sidner: application to

travel agency dialogue

• All utterances (except acceptances and

rejections) are seen as proposals

• example:

– U: Hi, my name is NN [propose]

– S: Hi, what can I do for you [accept, ...]

• Why is this counterintuitive?

– a person’s name is usually not a negotiable

issue

Negotiation vs. acceptance

• Allwood, Clark: levels of understanding and acceptance

–

–

–

–

1.

2.

3.

4.

A

A

A

A

attends to B’s utterance

percieves B’s utterance

understands B’s utterance (grounding)

accepts or rejects B’s utterance

• Sidner and others sees negotiative dialogue as

proposals and acceptance/rejections

• this means that all dialogue is negotiative

– all assertions (and questions, instructions etc.) are

proposals

Negotiation vs. acceptance

• But some dialogues are negotiative in another

sense,

–by explicitly containing discussions about different

solutions to a problem, and finally deciding on one

–Negotiation in this sense is not Clark’s level 4

• proposals are dialogue moves on the same

level as questions, assertions, instructions etc.

• There’s a difference between

– accepting a proposal-move, and thereby adding a

possible solution, and

– accepting a proposed alternative as the solution

Two senses of

“negotiation”

• Negotiation in Sidner’s sense

– A: I’m going to Paris[propose P]

– B(1): OK, let’s see... [accept P]

– B(2): Sorry, we only handle trips within Sweden

[reject P]

• Negotiation in our sense

– U: flights to Paris on september 13 please

– S: there is one flight at 07:45 and one at 12:00

[propose two flights]

– U: what airline is the 12:00 one [ask]

– S: the 12:00 flight is an SAS flight [answer]

– U: I’ll take the 12:00 flight please [accept flight]

Remedies

• distinguish utterance acceptance

from “real” negotiation

• an account of counterproposals

which can account for the fact that

– a new proposal may concern the

same issue as a previous proposal,

– without necessarily being a

counterproposal

Negotiativity

• Negotiation is a type of problem-solving

• suggested characterisation of negotiation:

– DPs discuss several alternative solutions to some

problem before choosing one of them

• Negotiation does not imply conflicting goals

– perhaps not 100% correspondence to everyday use

of the word “negotiation”, but useful to keep

collaborativity as a separate dimension from

negotiation

– this is also common practice in mathematical game

theory and political theory

Negotiation tasks

• Some factors influencing negotiation

– distribution of information between DPs

– distribution of responsibility: whether DPs must

commit jointly (e.g. Coconut) or one DP can make

the comittment (e.g. flight booking)

• We’re initially trying to model negotiation in

flight booking

– sample dialogue

•

•

•

•

•

U:

S:

U:

S:

U:

flights to paris on september 13 please

there is one flight at 07:45 and one at 12:00

what airline is the 12:00 one

the 12:00 flight is an SAS flight

I’ll take the 12:00 flight please

– Sys provides alternatives, User makes the choice

– Sys knows timetable, User knows when he wants to

travel etc.

Degrees of negotiativity

• non-negotiative dialogue: only one

alternative is discussed

• semi-negotiative dialogue: a new

alternative can be introduced by

altering parameters of the previous

alternative, but previous alternatives

are not retained

• negotiative dialogue: several

alternatives can be introduced, and old

alternatives are retained and can be

returned to

Semi-negotiative dialogue

• Does not require keeping track of

several alternatives

• Answers must be revisable (to

some extent)

• Example of limited seminegotiative dialogue

– Swedish SJ system (Philips): ”Do you

want an earlier or later train?”

Issues Under Negotiation i

(fully) negotiative dialogue

• IUN is question e.g. what flight to take

• In an activity, some questions are

marked as negotiable issues

– other questions are assumed to be nonnegotiable, e.g. the user’s name in a travel

agency setting

• Each IUN is associated with a set of

proposed answers

– Needs a new IS field: SHARED.IUN of type

assocset(question,set(answer))

Alternatives in negotiation

• Alternatives are possible answers to an IUN

• a proposal has the effect of introducing a new

alternative to the Issue Under Negotiation

• An IUN is resolved when an alternative is

decided on, i.e. when an answer to it is

accepted

• In some cases, the answer to IUN may consist

of a set of alternatives (e.g. when buying CDs)

an optimistic approach to

utterance acceptance

• DPs assume their utterances and moves are

accepted (and integrated into SHARED)

– If A asks a question with content Q, A will put Q

topmost on SHARED.QUD

• If addresse indicates rejection, backtrack

– using the PRIVATE.TMP field

• No need to indicate acceptance explicitly; it is

assumed

• The alternative is a pessimistic approach

– If A asks a question with content Q, A will wait for an

acceptance (implicit or explicit) before putting Q on

top of QUD

Example

• IUN is ?x.sel_flight(x) (“which is the chosen

flight”?)

• A: flight to paris, december 13

– answer(dest(paris)) etc.;

• B: OK, there’s one flight leaving at 07:45 and

one at 12:00

– propose(f1), propose(f2),

– answer(dep_time(f1,07:45)),

answer(dep_time(f2,12:00))

• ....

• A: I’ll take the 07:45 one

– answer(sel_flight(X), dep_time(X, 07:45)),

– after contextual interpretation: answer(sel_flight(f1))

B: OK, there’s one flight leaving at 07:45 and

one at 12:00

AGENDA =

PLAN =

PRIVATE =

{ findout(?x.sel_flight(x)) }

findout((?x. ccn(x))

book_ticket

BEL = {flight(f1),

dep_time(f1,0745), ... }

TMP = (same structure as SHARED)

IUN =

< ?x.sel_flight(x){ f1, f2 } >

SHARED =

COM =

dep_time(f1,0745),

dep_time(f2,1200)

dest(paris), ...

<>

LM = {propose(f1), propose(f2),

answer(dep_time(f1,07:40),...}

QUD =

Issues Under Negotiation:

Summary

• proposed alternatives can concern

the same issue, without conflicting

• not all issues are negotiable:

depends on the activity

• a formal account in line with the

use of Questions Under Discussion

in GoDiS

Future work

• implementation

• exploring negotiation in other

domains

• relating IUN to global QUD; are

they both needed?

• dealing with conflicting goals

CD dialogue

– U: Records by the Beach Boys

– S: You can buy Pet Sounds, Today, or Surf’s

Up

– U: Which is the cheapest?

– S: Pet Sounds and Today are both 79:-,

Surf’s Up is 149:– U: Hmm... I’ll get Pet Sounds and Today