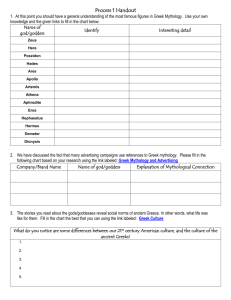

Question #1

advertisement

Introduction to Mythology Greek and Roman mythology is quite generally supposed to show us the way the human race thought and felt untold ages ago. Through it, according to this view, we can retrace the path from civilized man who lives so far from nature, to a man who lived in close companionship with nature. The real interest of the myths is that they lead us back to a time when the world was young and people had a connection with the earth, with trees and seas and flowers. When these stories were being made, little distinction had been made between the real and the unreal. Question #1 In earlier times, “the imagination was vividly alive and not checked by reason.” But the imagination of primitive beings differed from the imagination of the Greeks. Explain this difference between primitive and classical mythology. Answer #1 Classical mythology comes from a more civilized time. Thus, the Greeks tended to see lovely nymphs in the forest and other pleasant visions, while the more primitive peoples saw ugliness and terror lurking everywhere. We, for a moment, can catch a glimpse of that strangely and beautifully animated world. But a very brief consideration of the ways of uncivilized peoples everywhere is enough to prick that romantic bubble. Nothing is clearer than the fact that primitive man, whether in New Guinea today or eons ago, is not a creature who peoples his world with bright fancies and lovely visions. Horrors lurked in the primeval forest. This dark picture is worlds apart from the stories of classical mythology. Of course the Greeks too had their roots in the primeval slime. But what the myths show is how high they had risen above the ancient filth. Only a few traces of that time are found in the stories Question #2 Specifically, how did the gods of Greece differ from the gods of Egypt or Mesopotamia? Answer #2 Greek gods were in human form, while the gods of other cultures were part cat or bird or lion. gods of ancient Egypt Anubis, the jackal-headed guardian deity The sun god Horis Horus, a guide and protector Question #3 Edith Hamilton speaks of “the miracle of Greek mythology.” What does she mean? Answer #3 Since the Greeks believed in human gods, people could be more at ease with them. While the halfhuman, half-beast gods of the other cultures inspired fear, the Greek gods appeared more companionable. The Greeks made the gods in their own image. Mankind became the center of the universe, the most important thing in it. This was a revolution in thought. Human beings counted for little before. In Greece man first realized what mankind was. Until the Greeks, gods had had no semblance of reality. They were unlike all living things. In Egypt, a towering colossus, immobile, and deliberately made unhuman. Or a rigid figure, a woman with a cat’s head suggesting inflexible, inhuman cruelty. One need only to place beside them any Greek statue of a god, so normal and natural with all its beauty, to perceive what a new idea had come into the world. With its coming, the universe became rational. In the ancient world, people were preoccupied with the visible; they were finding satisfaction in what was actually in the world around them. The sculptor watched the athletes contending in the games and he felt that nothing he could imagine would be as beautiful as those strong young bodies. So he made his statue of Apollo. Greek artists and poets realized how splendid a man could be, straight and swift and strong. He was the fulfillment of their search for beauty. Ares, god of war Embodiment of beauty/heroism The first written record of Greece is The Iliad. Greek mythology begins with Homer, generally believed to be not earlier than a thousand years before Christ. The Iliad is written in a rich and subtle and beautiful language and serves as proof of civilization. The tales of Greek mythology do not throw any clear light upon what early mankind was like. They do throw an abudanance of light upon what early Greeks were like—a matter, it would seem, of more importance to us, who are their descendants intellectually, artistically, and politically, too. Nothing we learn about them is unfamiliar to ourselves. A passage from The Iliad Andromache expresses her fears and pleads with Hector not to return to battle. Hector replies: Lady, these many things beset my mind no less than yours. But I should die of shame before our Trojan men and noblewomen if like a coward I avoided battle, nor am I moved to. Long ago I learned how to be brave, how to go forward always and to contend for honor, Father’s and mine. Honor—for in my heart and soul I know a day will come when ancient Ilion [Troy] falls, when Priam and the folk of Priam perish. Human gods naturally made heaven a pleasantly familiar place. The Greeks felt at home in it. They knew just what the divine inhabitants did there, what they ate and drank and where they banqueted and how they amused themselves. Of course, they were still to be feared; they were very powerful and very dangerous when angry. Question #4 What are some of the “dark spots” to which the author refers? Answer #4 Sometimes Greek gods behaved cruelly or indecently. Sometimes traces remained of the older beast-gods in the satyrs or other partly human creatures. There are also stories which clearly point to a time when there was human sacrifice, but there are so few stories that do so. Of course the mythical monster is present in any number of shapes, but they are there only to give the hero his means of glory. What could a hero do in a world without them? Question #5 How does Edith Hamilton define or explain mythology? Answer #5 She stresses that it is not an account of Greek religion, but rather an explanation of something in nature. However, religion is part of mythology and some myths explain nothing at all. 4 functions of myth Question #6 How does the author explain the different views of the same god? Answer #6 Mythology grows and develops as a people grow and develop. There may be numerous versions of a single story coming from various times or authors. Homer and Hesiod both describe Zeus as chief of the gods but their views of the character of Zeus differ.