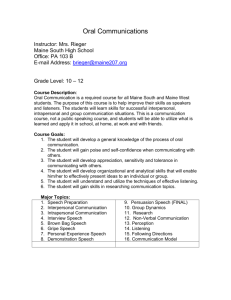

Acquisition Lesson Plan - Teaching American History: Freedom

advertisement

Research Lesson Plan: The “Maine” Mystery in American History Author: Fran O’Malley, Delaware Social Studies Education Project. Targeted Grade Level: 4-12 (with modifications for developmental ability) Essential Question: Why might there be different accounts or interpretations of the same event? Formative Assessment Prompts: Instructional Chunk #1: What questions should researchers ask of sources? Instructional Chunk #2: Is any conclusion about what happened acceptable? Explain. Instructional Chunk #3: Why might there be different accounts or interpretations about the past? Standard(s) Addressed: History 3 [Interpretation] Grades 4-5: Students will explain why historical accounts of the same event sometimes differ and relate this explanation to the evidence presented or the point-of-view of the author. History 3 [Interpretation] Grades 9-12: Students will compare competing historical narratives, by contrasting different historians' choice of questions, use and choice of sources, perspectives, beliefs, and points of view, in order to demonstrate how these factors contribute to different interpretations. Problematic Prior Knowledge Addressed (e.g. problematic prior knowledge refers to prior knowledge, preconceptions, misconceptions, and misinformation about history in general and American history in particular that are at variance with currently accepted understandings within the history profession or a preponderance of evidence in cases of misinformation, and that slow down or prevent learners from modifying or exchanging the PPL for the accepted understandings.) Once a source is judged not to be good for one investigation, it loses its value. Some sources are unbiased. Weighing the evidence is a process of counting the number of sources for one conclusion versus another. Any interpretation of the past is acceptable. History is just a bunch of facts. 1 Activating Strategies: Strategy 1: Cheating Scandal Sources – students evaluate sources in the context of alleged cheating on a test. Strategy 2: Cheating Scandal Evidence – students weigh evidence in preparation for drawing conclusions about allegations of cheating. Key Vocabulary to preview Evidence Point of view Perspective Sources Account Teaching Strategies: Case studies Think-Pair-Share Evidence Construction Graphic Organizer(s) Used: Acrostic Summarizer. Materials Needed: Copies of Resources #1-7 (below). Scissors for small group work. Aluminum foil (optional). Differentiation Strategies: Instructional Plan (procedures): Instructional Chunk #1: What questions should researchers ask about sources? I. Procedures 1. Present (project) the following visual to the students (large copy available as Visual 1): 2 The Scandal A social studies teacher has strong suspicions that a student named Bob cheated on a test. The social studies teacher plans to investigate the alleged act of cheating by questioning some of the other students in the class. . The social studies teacher has asked the science teacher on his middle school team to help out with the investigation. 2. Tell the students that the teachers have identified a list of 4 sources or “witnesses” who he thinks might prove valuable as he investigates the alleged act of cheating. Present (Visual 2) the following list to the students and read each source description – one at a time - to the students. Witnesses Erin: sits in front of the room. Likes Bob very much. Katie: sits next to Bob in the back of the room. Sean: sits next to Bob in the back; dislikes Bob greatly. Ryan: sits in the middle of the room. 3. Mapping Activity: ask students to take out a blank piece of paper and map the scene of the “Classroom Cheating Scandal” (i.e. where Bob, Erin, Katie, Sean, and Ryan would have been sitting). 4. Think-Pair-Share: Ask students to work with their partner to analyze the quality of the witnesses or sources. Which ones appear most credible? Which ones appear least credible? Ask the students to create a list of “good” and “bad” sources for the teachers. Tell them that they must be able to explain why they considered each source “good” or “bad.” Allow a few minutes for the pair to complete the tasks then, starting with “Erin,” ask volunteers to explain their analyses and conclusions about each witness (a.k.a. source). 5. Whole Group Discussion: Ask the students the following questions: A. What would the social studies teacher conclude if he used Sean as his only source of information? [Probably response: Bob cheated] B. What would the science teacher conclude if he used Erin as his only source of information? [Probably response: Bob did not cheat] C. Why might two different teachers arrive at two different conclusions about the same event? [Response: they relied on different sources] D. Can you think of other situations in which two people might [or did] arrive at different conclusions because of a reliance on different sources? 3 6. Mini-Lecture: Making Transfer Explicit. Explain to students that transfer is one of the important aims of education. Transfer refers to the ability to use what one learns in one situation and apply it or solve problems in a new but similar situation. For example, a student who learns to drive a car uses that understanding to drive a truck. Note that a student who can analyze the quality of sources in a hypothetical situation like that presented in “The Cheating Scandal” can provide solid evidence of learning or understanding by transferring that skill successfully to similar investigations or tasks. Ask students if they can think of other examples of transfers. 7. Formulate Analytic Questions: Distribute copies of Resource #1: Questions to Ask of Sources. Ask students to reflect on their thinking as they analyzed potential witnesses for the cheating scandal. Tell them to work with their partners and use Handout 1 to create a list of questions that they might ask about any witness or source when faced with the task of deciding which source might be best or most credible. [Do not share all of these with the students but reasonable questions might include:] a. Was the witness there when the event occurred? b. Is it likely that the witness was attentive to the event? c. Was the witness in a position to observe the event? d. Did the witness have any potential biases? If so, what were they? e. Which witness appears to have had the least bias…the most bias? Why? f. Were the witness’s recollections consistent with the recollections of others? Ask each group to share one question and continue moving from group to group until you have exhausted all of the questions [or have groups share their best question]. Ask the students to record any questions that do not appear on their list. Then, ask the students to work with their partners to eliminate or rephrase any question that could not be used to evaluate any source. In other words, you want them to develop questions that generalize or apply to a wide range of sources [i.e. are transferable], not just the “Cheating Scandal” task. After a few minutes, ask volunteers to share questions that they either eliminated or rephrased. II. Debrief: ask the students… III. Why is it important to ask questions of (or interrogate) sources? Which questions do you think are most important to ask? Can a source that is not useful for one investigation be useful for a different one? Explain and/or give an example. Check for Understanding/Summarizing Activity: 3-2-1 3 - List 3 questions you should ask of all sources. 2- List 2 reasons why these questions should be asked. 1 – List 1 thing that might happen if you did not question sources. Instructional Chunk #2: What conclusion does the evidence point to in the cheating scandal mystery? Suggest to students that the previous activity got them to think about bias and the reliability of sources. Another important practice of historians involves weighing evidence. For the most part, all we have are people’s opinions about whether Bob cheated. Our goal now is to move from opinions which may or may not be supported by evidence, to evidence based conclusions or interpretations. 4 Place students in small groups, give each group a pair of scissors, and distribute copies of … Resource # 2: Classroom Cheating Mystery Evidence. Resource # 3: Bob’s Test Results. Resource # 4: Molly’s Test Results. Have students cut out the conclusion “headers” at the bottom of the page and place them side by side on the top of their desks or tables. Then, ask them to cut out the evidence strips, discuss which conclusion it supports, and place the strip under that conclusion. Once they assign each piece of evidence to a conclusion header, they are to discuss which conclusion is supported by the preponderance of evidence. Check for Understanding/Summarizing Activity: Have students share their conclusions and the evidence that informed them. Debrief: Ask the students… Do we “know” for certain whether Bob cheated? What does this activity suggest about what it means to “know” in history when what people are studying what happened in the past? Is any conclusion about what happened OK? Explain. Instructional Chunk #3: What conclusion does the evidence point to in the USS Maine mystery? Present the following information to the students: In 1898 Cuba was still a colony of Spain but its people were trying to break away from Spain just as our original 13 colonies broke away from England in 1776. Americans started hearing reports that Cubans were suffering because the Spanish were rounding up civilians and throwing them in detention camps. Over time, Americans began supporting the Cubans in their struggle for independence. In January of 1898, the United States sent the battleship USS Maine to Havana Harbor in Cuba. Some think that the United States sent the USS Maine to protect Americans and their businesses in Cuba. Others think that the United States sent the ship as a way of telling Spain that the United States did not approve of their policies in Cuba and to warn Spain that the United States might use its military to support the Cubans. At 9:40 p.m. on February 15, 1898, an explosion rocked the USS Maine while it was stationed in Havana Harbor, Cuba. Two hundred and sixty six American sailors were killed. Tell the students that, to this day, the cause of the explosion on the USS Maine remains a mystery. Regardless, it served as the event that triggered the United States into what an American Secretary of State described as a “splendid little war” with Spain. Have students brainstorm possible causes of the explosion. Suggest the following if they do not: • intentional external explosion. • unintentional external explosion. • intentional internal explosion. 5 • unintentional internal explosion. Distribute sheets of aluminum foil to students. Ask them to imagine that the foil is the frame of the USS Maine and to manipulate the foil as they consider the two questions below: What would the ship’s frame look like if there was an internal explosion? Why? What would the ship’s frame look like if there was an external explosion? Why? Invite volunteers to share & demonstrate their responses. Discussion: Given the background information provided above, is there any reason why… Cubans might want to blow up the Maine? Spaniards might want to blow up the Maine? Americans might want to blow up the Maine? Emphasize the importance of examining evidence as researchers try to unravel the mysteries of the past including what caused the explosion on the Maine. Place students in small groups. Distribute copies of Resource # 5: Maine Mystery Evidence Blocks. Review the directions at the top of Resource #5. Students will assign evidence to different theories in preparation for drawing conclusions about what caused the explosion on the USS Maine. Check for Understanding/Summarizing Activity: Presentations: Have each group present their conclusion and the evidence that they used to support it. Be sure to highlight differences in interpretations and link them to ideas presented in Delaware history standard 3. For example… Evidence presented. Use and choice of sources. Instructional Chunk #3: At what conclusion have other investigators arrived regarding the causes of the explosion on the USS Maine? Procedures Think-Pair-Share: have students work with an elbow partner. Distribute copies of Resource #6: Continuity v Change over Time. Ask them to read the conclusions of different groups that have investigated the explosion on the USS Maine over time and answer the three questions that follow. Have the conclusions about the causes of the explosion on the USS Maine remained the same or changed over time? Explain. Why might there be different explanations of the same event in history? How might one’s use and choice of sources affect his or her conclusions? Alternate Strategy - Jigsaw: Place students in groups of 5 and give each student a different text box on Resource #6. Have them read, paraphrase, and share the conclusions of their investigative body (e.g. Sampson Board of Inquiry) with the others in their group. 6 Discussion: pose the follow questions to the whole class: Does it matter when a conclusion is reached e.g. 1898 versus 1998? Explain. Are conclusions reached more recently better that those reached earlier? Explain. Do any of the conclusions reached by the 5 investigative bodies seem more persuasive to you? Why? Have any of the investigative conclusions presented on Resource #6 caused you to change your conclusion about the causes of the explosion on the USS Maine? Explain. Summarizing Strategy: Acrostic Summarizer: Have the students complete Resource #7: Acrostic Summarize using the word “Maine.” Limit them to statements flowing from the essential questions and content in the lesson. 7 Resource #1 Questions to Ask of Sources Directions: work with a partner to generate a list of questions that you might use during an investigation to evaluate sources. Example Why was this document written (or why is this person testifying)? List your questions in the spaces below: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Authors: ______________________________ ________________________________ 8 Resource #2 Classroom Cheating Mystery Evidence Directions: 1. Cut out the headers that appear below then place them in 3 different sections of your desk or table. 2. Then, cut out the evidence strips below the headers. 3. Read each piece of evidence to those in your group then place the evidence strip under the Theory (or header) that it best supports. 4. Discuss all of the evidence with those in your group then reach agreement on which conclusion the evidence best supports i.e. Bob cheated; Bob did not cheat; or there is not enough evidence to decide. Headers Bob Cheated (Evidence). Bob Did Not Cheat (Evidence). Unclear evidence. Evidence Strips A. student graded test sheets (handouts). B. the “witnesses” (Erin, Katie, Molly, Sean, Ryan). 1. Katie thinks Bob cheated. 2. Sean said Bob cheated. 3. Erin does not think Bob cheated. 4. Ryan isn’t sure if Bob cheated. C. Bob’s average test grade for the marking period is a 72. D. Molly sits in the desk right in front of Bob. E. desks are arranged tightly in rows. 9 F. Bob and Molly just started dating. G. Bob and Molly say that they study together. H. class average on the test was an 81. I. teacher curves tests based on highest score. J. Bob and Molly both got the highest grades in the class. K. Bob’s teacher observed that Bob was acting peculiar during most of the test and saw him looking in Molly’s direction on several occasions. L. Bob needed an A to pass for the marking period. M. Bob and Molly turned their paper in at the same time. N. Bob is known to have cheated only 1 time since being in school. 10 Resource # 3: Bob’s Test Results 10/19/11 11 Resource # 4: Molly’s Test Results 10/19/11 12 Resource # 5 Maine Mystery Evidence Blocks Directions: 1. Cut out the headers that appear below then place them in 3 different sections of your desk or table. 2. Then, cut out the evidence blocks below the headers. 3. Read each piece of evidence to those in your group then place the evidence block under the Theory (or header) that it best supports. 4. Discuss all of the evidence with those in your group then reach agreement on which theory the evidence best supports. Header 1 Mine Theory A mine in the water caused the explosion on the USS Maine. Header 2 Coal Fire Theory A fire inside the ship caused the explosion on the USS Maine. Header 3 Alternative Theory _________________________ caused the explosion on the Maine. 1. Divers spotted a large hole on the floor of Havana harbor. 2. The inward bending of the plates can be caused by water displacement occurring at the same time the front of the ship was breaking away from the rear. 3. The divers who examined the bottom plates of the Maine reported that they were all bent inward. 13 4. No one reported seeing 5. The only reason that two any dead fish in the harbor explosions would have and these would have been been heard is if something seen if there had been an besides the magazine had external blast. exploded, such as a mine. 7. No one reported seeing a geyser of water thrown up during the explosion, a common sight when mines explode underwater. 10. Bunker A16 had not been inspected since 8 a.m. The explosion occurred around 9:40 p.m. There was ample time (12 hours) for an internal coal bunker fire to smolder into a disaster. 13. Several other ships sustained damage from coal bunker fires during the Spanish American war. 6. A number of witnesses stated that they heard two distinct explosions several seconds apart. If anything else besides a mine had triggered the magazine explosion, then witnesses would have only heard one blast, because the only explosion would have been that of the magazines. 8. Discipline on the Maine was excellent. There were regular inspections of coal bunkers for hazards, as well as the implementation of precautions for preventing bunker fires, were diligently carried out. 9. The Maines' temperature sensor system did not indicate any dangerous rise in temperature on the morning of the last inspection. 11. When Bunker A16 was inspected the morning of the disaster, the temperature was only 59 degrees Fahrenheit 12. Normally, spontaneous combustion does not occur unless there is a heat source to speed up the process 14. Spontaneous combustion of coal was a fairly frequent problem on ships built after the American Civil War. Coal was exposed to air, oxidized and began burning at 180 degrees. Heat transferred to magazines causing explosion. 15. The Maine carried a type of bituminous coal (New River coal) that rarely combusted. 16. Bunker A16 was not situated by a boiler or any other external heat source 14 Resource # 6 Continuity v Change over Time Directions: Read the summaries of major investigations of the Maine explosion then answer the questions that follow. The Sampson Board of Inquiry (1898) Headed by Captain William T. Sampson, United States Navy. Employed divers, photographic evidence, and eyewitness testimony. Finding: The Maine had been blown up by a mine, which in turn caused the explosion of her forward magazines. “The court has been unable to obtain evidence fixing the responsibility for the destruction of the Maine upon any person or persons.” Spanish Investigation Commission (1898) Finding: The explosion on the Maine was caused internally, probably due to an accident. Witnesses heard a sharp explosion (not dull concussion) and saw no geyser. Vreeland Court of Inquiry (1911) Headed by Rear Admiral Charles E. Vreeland, United States Navy. The US Army Corps of Engineers built a massive cofferdam, sank huge pylons, then pumped out seawater and exposed the wreck. The Vreeland team took and numbered pictures of the explosion area. Satisfied, they hauled the wreck out to sea and buried bodies at Arlington National Cemetery. Finding: The explosion of the magazines on the Maine was triggered by an external blast, but the damage to the ship was much more extensive than the Sampson Board had thought. The blast occurred further aft on the ship. Rickover Investigation (1976) Began as a result of interest on the part of Admiral Hyman G. Rickover (“father of the nuclear navy”), United States Navy. Mr. Ib S. Hansen of the David W. Taylor Naval Ship Research and Development Center and Mr. Robert S. Price of the Naval Surface Weapons Center volunteered to look at the evidence. Finding: The explosion of the magazines was caused by a coal bunker fire, which had heated the magazines to the point of explosion. “There is no evidence that a mine destroyed the Maine.” National Geographic Investigation (1998) National Geographic commissioned this study by Advanced Marine Enterprises which conducts warship design studies for the US Navy. Used computer modeling and heat transfer engineering studies. Finding: “[I]t appears more probable than was previously concluded that a mine caused the inward bent bottom structure and the detonation of the magazines.” Essential Question #1: have the conclusions about the causes of the explosion on the USS Maine remained the same or changed over time? Explain. Essential Question #2: Why might there be different explanations of the same event in history? Essential Question #3: How might one’s use and choice of sources affect his or her conclusions? 15 Resource # 7 Acrostic Summary Directions: use the letters in the word “M A I N E” write statements that summarize important things you learned in this lesson. The first one is partially completed for you to show you how this works. You can complete the first statement by filling in the blanks. M ost of the students in class concluded that ______________________ caused the explosion on the Maine. I agree/disagree (circle one) because ______________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________. A I N E 16