The Captive Mind

advertisement

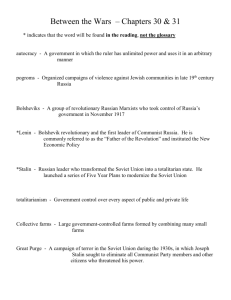

The Captive Mind Understanding the Imposition of Communist Rule The Socio-economic Context According to Jan Gross, we must consider WWII and the Nazi occupation as crucial factors explaining the relative ease with which communist rule was established in Eastern Europe and the context in which individuals responded to that imposition: “comprehensive processes of social change conducive to the etatization and leveling of the affected societies were set in motion. Apparently, the Soviet victory over the Nazis did not entail such a radical break as is customarily portrayed.” (p. 23, “Themes for a social history…”) Essential Continuities from Nazi to Soviet Occupation: Economic • Forced economic growth -- habituating the populations of Eastern Europe to the idea that growth and the “acceleration of social change” are produced by planning and the targeting of specific sectors for advancement • Forced “decoupling” from international trade and autarchic development already achieved under German occupation facilitated Soviet control over the region • State ownership and intervention in the economy already prevalent under the Nazi occupation as exemplified by the appropriation of Jewish properties. Social-Behavioral Consequences of Nazi Economic Polices • Destruction of property rights – suppressed legitimate entrepreneurial initiative and promoted the turn to black market activities • Collapse of work ethic and labor discipline – economic growth achieved on the basis of forced labor not labor productivity • Alienation of work -- as “one of the major avenues for socializing people into cooperation”… work “suddenly lost its capacity for binding the social fabric together.” (p. 21) Cumulatively, these behavioral patterns meant that the imposition of communist labor practices did not radically conflict with existing standards and practices. Demographic Changes Produced Under Nazi Occupation • Loss of population through death, deportation and displacement “created opportunities for upward social mobility,” as the younger generation and lower classes took over the occupations of those lost • Loss of population (especially Jews and Germans) produced more homogenous states that more closely approximated the ‘ideal’ nation-state The Communists were able to take credit for both outcomes thereby helping to legitimate their rule. Social Psychology Effects of Occupation • Displacement, deportation and repatriation all created passive population groups dependent on state authority and prone to infantile ‘regression’ easily amenable to control by incoming Soviet-backed authorities. • Experiencing conditions of extreme violence and brutality during the occupation made Soviet tactics of control seem ‘normal’ or even tame in comparison. On collaboration While the socio-economic conditions of occupation facilitated the imposition of Soviet rule, political and ideological circumstances also determine the extent to which local elites will collaborate with invading powers. As Gross elaborates, collaboration with the Nazis was determined by several factors that can also inform our understanding of why local populations in Eastern Europe collaborated with Soviet authorities. When does collaboration take place? • First and foremost, occupying powers must offer collaboration as an option for local populations • In turn, locals will be more prone to collaborate if intense political factionalization leads them to see each other as worse enemies than the external occupiers; if political groups have some ideological affinity with the occupiers (the Nazis, for example, could count on the support of “reactionary traditionalists” and the radical right); if individuals are governed by a logic of ‘realism’ that dictates “accommodation with the new circumstances” rather than futile resistance. Accommodation that can then be justified by the hope that the behavior of the occupiers will thereby be moderated and/or that history, the future, will ultimately vindicate the decision to collaborate. Holding collaborators accountable • Under these circumstances can we hold collaborators accountable? According to Gross, they “can be held accountable only if they had options, alternative choices…” Milosz: Judgment and Understanding In Milosz’s account of his friends and colleagues who decided actively to support the imposition of Soviet rule in Poland, he attempts to comprehend the reasons behind this decision while also judging their actions, thereby attempting to hold them accountable for succumbing to the “logic of History.” And he hopes that they too have some awareness of the terrible decision they made as in the case of Gemma: “But sometimes he is haunted by the thought that the devil to whom men sell their souls owes his might to men themselves, and that the determinism of History is a creation of human brains.” (p. 174) But is his judgment valid according to Gross’ criterion that only in the context of free choice can collaborators be held accountable? Are the life stories he recounts constructed to show fateful moments of choice and conscious decision or do they show the painful inevitability of their behavior given their particular psyches? And how their psyches interacted with the war torn environments they found themselves in. Milosz and the Social History of the Imposition of Communist Rule Remarkably, given the fact that Milosz wrote his book in 1953, his account prefigures the social history of the era suggested by Jan Gross writing in 2000. While Gross does not mention memoir and individual memory in this particular essay, in general his work does build on memoirs – using individual memories to challenge conventional accounts of history, so, implicitly at least, he may have been drawing on Milosz’s account to inform his social history. Milosz and Gross: Overlapping Observations • How the violence and brutality of the war impacted individuals (most evident in the case of Beta); and how the Soviets used hatred of the Nazis in their “psychological preparation of the country” (p. 126) • How displacement/emigration and repatriation can generate a sense of disorientation easily exploited by Communist authorities (most evident in the case of Delta) • How the political economy of the war years pre-disposed people to accept communism – especially the destruction of private property (p. 164) • How alienation, specifically the alienation of intellectuals from the surrounding society, made them susceptible to the seductive offers made by the Soviets (most evident in the case of Alpha) • How pessimistic realism, political divisions and ideological predispositions can facilitate collaboration (most evident in the case of Gamma) In general Milosz’s account depicts the interactive dynamic underlying collaboration as outlined by Gross: how/why collaboration is offered as an option by occupiers (E.g., “Because Communism recognized that rule over men’s minds is the key to rule over an entire country, the word is the cornerstone of this system.” p. 161 --hence the offer of collaboration made to writers and poets), and how/why it is accepted by those targeted. Milosz’s account also provides insights into why the issue of who supported the communist regime and who collaborated with the secret police is still such a polarizing issue in Polish political life. Specifically, he demonstrates the extent to which these individuals were willing to overlook the extent to which the Soviets were as culpable as the Nazis in the destruction of Polish life and society. For example, those Poles who passed the war in the SU, like Gamma, were well aware of the crimes of Stalin, including the murders of Polish officers at Katyn (p. 156). From the perspective of current conservative-nationalist politicians, to knowingly assist in the imposition of such a murderous system on Poland is a treason for which there should be no statute of limitation.