PPT

advertisement

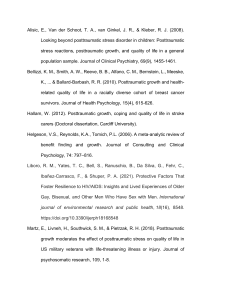

The Practice and Ethics of Using Expressive Therapies with Traumatized Clients Scott Pelking, MFA, MA, LPCC Why Use Expressive Therapies? Expressive therapies often provide unexpected insight to the client and the therapist. Unlike with talk therapies, expressive therapies are difficult for the client to hide important information—it may come out symbolically or literally. “Expressive methods can and do stimulate the flow of traumatic memories, either in the form of trauma narratives (stories about the event) or implicit experiences (sensory memories of the event) because of the tactile, kinethetic, auditory, inherent to creative activities.” (Malchiodi, 2008) Sometimes it’s difficult for clients— especially young ones––to talk about traumatic memories. They may do better playing, drawing, painting, or working in the sand tray. Young children think concretely. Play therapy allows children to process abstract occurrences into more concrete experiences in a language they can understand: play. Almost everyone connects with music. If using songs, find and provide copies of the lyrics. Encourage clients to bring in or suggest songs or other music they find meaningful. Some clients find it easier to talk while they’re busy doing something else. Ethical Considerations Expressive work should be taken for what it is, nothing more. Some clinicians read more into the products of expressive work than is prudent. “Your initial inclination will be to glance at a sketch and start interpreting….Don’t. The one reliable thing you can do is to see how it feels to you. Then put it in a spot where you will see it often for a few days. “If you notice yourself placing phallic references all over or negativity about one area consistently, stop and consider yourself. Are you inserting your experiences into the interpretation?” (Coles, 2003) Use digital photo to document sand tray scenes, art work, and even play room constructions. Include color prints of the photos with session documentation. Be careful to keep the client out of the picture. Be watchful for abreaction, and be prepared to address it. Sometimes expressive therapy can be surprisingly overwhelming in its effect on the client— and the therapist. Know what you’re doing. As with any other therapeutic approach, get sufficient training and/or supervision before using expressive therapy interventions. Integrate expressive therapy with your own theoretical foundation. Interventions must make therapeutic, clinical sense in terms of treatment. Differences between Dynamic and Stagnant Posttraumatic Play (Gil, 2006) Differences between Dynamic and Stagnant Posttraumatic Play (Gil, 2006) Dynamic Posttraumatic Play • Affect becomes available • Physical fluidity becomes evident • Interactions with play become varied • Interactions with clinician become varied Dynamic Posttraumatic Play • Play changes, or new elements are added. • Play occurs in different locations • Play includes new objects • Themes differ or expand. Dynamic Posttraumatic Play • Outcomes differ, and healthier, more adaptive responses emerge. • Rigidity of play loosens over time • After-play behavior indicates release or fatigue. Dynamic Posttraumatic Play • Out-of-session symptoms may remain unchanged or peak at first, but then decrease. Stagnant Posttraumatic Play • Affect remain constricted. • Physical constriction remains. • Interactions with play remain limited. • Interactions with clinician remain limited. Stagnant Posttraumatic Play • Play is precisely the same. • Play is conducted in the same spot. • Play is limited to specific objects. • Themes remain constant. Stagnant Posttraumatic Play • Outcomes remain fixed and nonadaptive. • Play remains rigid. • After-play behavior indicates constriction/tension. • Out-of-session symptoms are unchanged or increase. References Coles, J. (2003). Signals from the child: Learn to read the secrets of drawings and refrigerator art. Denver CO: EMBA House, LLC. Gil, L. (2006). Helping abused and traumatized children: Integrating directive and nondirective approaches. New York: The Guilford Press. Quoted in Malchiodi, C. A. (2008). Ethics, evidence, and cultural sensitivity. In Malciodi, C. A. (2008). Creative interventions with traumatized children. 34. New York: The Guilford Press. Groke, D. and Wigram, T. (2007). Receptive methods in music therapy. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsely Publishers. References Henderson, P., Rosen, D., and Mascaro, N. (2007). Empirical study on the healing nature of mandalas. Psychology of Creativity, Aesthetics, and the Arts. Vol 1, No 3, 148-154. Malchiodi, C. A, (2008). Ethics, evidence, and cultural sensitivity. In Malciodi, C. A. (2008). Creative interventions with traumatized children. 22- 40. New York: The Guilford Press.