36x48 Horizontal Poster

St. George’s University

Temporal Variation of Bacterial Indicators in Coastal Waters of Southern Grenada, West Indies

By V. A. Amadi

1

, J. Peters

2

, and S. Giesler-Kotelnikova

1

1

Microbiology and Immunology, School of Medicine, St. George’s University, Grenada;

2

Meteorological Services, Maurice Bishop

International Airport, St. George’s, Grenada.

Introduction

• Tropical waters of Caribbean region including Grenada are popular, used for year-round recreation, and resources from the coastal water serve as a main source of livelihoods for majority of the community

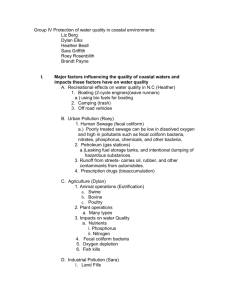

(Figure 1) [1]. Monitoring of coastal water quality is important for public health. Microbial pollution may result in economic loss due to closure of recreational beaches and sea food harvesting areas [2].

•

Coastal water quality have been monitored by Environmental

Testing Unit (ETU) of St. George’s University (SGU) since 2003 using fecal-indicator bacteria such as fecal coliforms and enterococci to evaluate potential health risks [3].

•

The presence of indicators may be strongly influenced by several factors including rainfall, direction of currents, numbers of yachts, tourists and students visiting the island, and sewage system problems leading to relatively short periods of elevated fecal pollution due to sewage runoff.

•

Rainfall can have a significant effect on the density of fecal indicators in recreational waters [4]. Rainfall usually increases indicator densities to high levels because animal wastes are washed from forests, pasture land and urban settings into the recreational water body, and treatment plants are overwhelmed by rainwater causing sewage to bypass treatment [5].

•

Our previous study have shown the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial indicators and other opportunistic pathogens in the coastal waters of Grenada [6, 7], however it is not known if the density of these organisms is affected by rainfall. This is a first report documenting the effect of rainfall on the variation of indicators in coastal waters of Grenada.

Aim of the study

• To demonstrate temporal variation and determine the effect of rainfall on variation of bacterial indicators in coastal waters of

Southern Grenada.

• Determine diversity of indicators and compliance of coastal waters with EPA and WHO guidelines of 200 fecal coliforms /100ml and

35 fecal enterococci /100ml.

Methods

• During the period of November 2008 and November 2010, 116 bacterial indicators were isolated from 255 water samples, which were collected on a weekly basis from four coastal sites including

Grand Anse Beach (GAB), Prickly Bay (PB), Black Sand Beach

(BSB) and True Blue Bay (TBB) in Southern Grenada, West

Indies (Figure 1) [6].

•

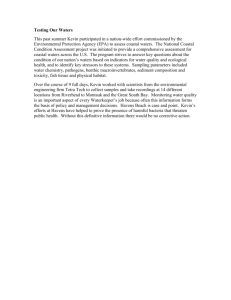

Pure cultures of the marine species were isolated from the confirmed positives MPN tubes and identified using phenotypic characteristics (Figure 2) [6, 7].

•

The densities of the bacterial indicators per 100 ml of water were determined using the MPN analysis on weekly basis from 2003 to

2011 [8].

•

Daily rainfall data were collected in Point Saline Peninsula at the

Meteorological Station of Maurice Bishop International Airport in

Grenada located next to BSB.

•

The volume of rainfall preceding each bacteriological analysis of water by 24 hours, between November 2008 and November 2010 was used to study the effect of rainfall on indicator variation, with the Correlation Analysis.

• The percentage compliance (X) with the EPA and WHO standard was inferred using the formula, X = A-B/A x 100, where A is total number of samples monitored, and B is number of samples that are above the required EPA and WHO recreational water quality guidelines during the period of six years (2005 – 2010).

250 ml of H

2

O

Results

• Out of the 255 samples collected from the 4 tested sites between

November 2008 and November 2010, the percent of samples polluted by the prevalent bacterial indicators were:

E. coli

19-28%,

K.

pneumoniae

11-22% in PB, and

E. faecalis

6-10%. Figure 3 presents the percentages of samples positive for fecal indicators isolated and identified.

• Between November 2008 and November 2010, clear difference in temporal variation of bacterial indicator counts was observed among the four studied sites (Figure 4). Correlation analysis resulted in lack of correlation between volume of rainfall and the levels of fecal coliforms (FC) detected in the seawater in GAB (r=0.15), PB (r =

0.01) and in TB (r = 0.11). However more significant but weak correlation was detected for fecal enterococci (FE) in BSB (r = 0.38) that may indicate that runoff of sewage contributed the observed pollutions (Figure 4).

• Table 1 presents the total number of samples monitored from the four respective sampling sites between 2005 and 2010.

•

Between 2005 and 2010, the highest compliance to EPA and WHO was in GAB 90 ± 10% of sampling occasions for FC and 89 ± 8% for

FE followed by PB 72

±

25% and 84

±

13%, while the lowest compliance was observed in BSB 69

±

17% and 74

±

11%, and in TBB

58 ± 23% and 63 ± 15%, respectively (Figure 5).

Table 1: Total number of samples monitored from the four coastal waters between 2005 and 2010

Year

Sites 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

GAB 46 41 34 30 28 45

PB 37 41 34 30 28 45

Figure 3: Percentage of samples positive for bacterial indicators from the 4 coastal waters of Southern

Grenada between November 2008 and November 2010

TBB 45 41 34 20 20 38

BSB 45 41 34 27 9 22

Samples were collected on a weekly basis (except for the period when the University policy did not allow the collection of sample from a particular site) from 4 coastal waters of Southern Grenada.

Variation of fecal indicators observed in True-Blue-Bay

No correlation between level of indicators and vol. of rainfall (r = 0.1121 for FC, and r = -0.0053 for FE)

Variation of fecal indicators observed in Black-Sand-Beach

Significant but weak correlation between level of indicators and vol. of rainfall (r = 0.0693 for FC, and r = 0.3819 for FE)

Figure 4: The effect of rainfall on the variation of fecal indicator organisms in coastal waters of Southern

Grenada http://www.skyviews.com/skyviews/maps/grenada/

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Board of Trustees of SGU, the Chancellor Dr. C.

Modica for providing funds for the research GSP-SGRI-10004-SGUIRB10008; the

SfAM studentship grant for their financial support; and the ETU team.

Photo By: Joshua Yetman (www.joshuayetman.com)

Grand Anse Beach Grenada

Figure 1: Map of Grenada showing the SGU, ETU sampling sites

Figure 2: Analyses used to quantify and identify bacterial indicators

Variation of fecal indicators observed in Grand-Anse-Beach

No correlation between level of indicators and vol. of rainfall (r = 0.0511 for FC, and r = -0.0097 for FE)

Variation of fecal indicators observed in Prickly-Bay

No correlation between level of indicators and vol. of rainfall (r = 0.0109 for FC, and r = -0.0063 for FE)

Figure 5: Percentage Compliance with the EPA and WHO standard for fecal coliforms and fecal enterococci between 2005 and 2012

Conclusions

•

Pollution observed in GAB, PB, and TBB was not a result of rainwater caused sewage or rhizosphere runoff. However, there is a weak indication that this is the case in BSB.

•

Highest level of compliance was observed for coastal water of GAB with 90

±

10% of sampling occasions for FC and 89

±

8% for FE, while the lowest compliance was observed in BSB 69 ± 17% and 74 ± 11%, and in TBB 58

±

23% and 63

±

15%, respectively.

References

1.

Fujioka, R. S. (2002). Microbial Indicators of Marine Recreational Water Quality. In C. J. Hurst, R. L. Crawford, G. R. Knudsen, M. J. McInerney & L. D.

Stetzenbach (Eds.), Manual of Environmental Microbiology (2nd ed., pp. 234-243). Washington, D.C.: ASM Press.

2.

Bartram, J., & Rees, G. (2000). Introduction. In J. Bartram & G. Rees (Eds.), Monitoring bathing waters - A practical guide to the design and implementation of assessments and monitoring programmes (pp. 1-15). New York: E & FN Spon.

3.

Patel, R. H., Pedersen, K. &Kotelnikova, S. (2010). The bacteriological analysis and health risk in the urban estuary of St. Geo rge’s Bay, Grenada, West Indies.

Journal of Environmental Health , (cover story), 73 , 22-28.

4.

WHO. (2003). Guidelines for safe recreational water environments Retrieved September 6, 2011, from http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/bathing/srwg1.pdf

.

5.

El Jarousha, A. K. (2006). Influence of seasonal environmental variables on the distribution of fecal indicator bacteria in seawater of Gaza strip. Annals of

Alquds Medicine, 2 (1), 18-12.

6.

Amadi, V. A., Lennon, D. E., Qureshi, A. A., Jungkind, D. L., and Kotelnikova, S. V. (2011). Occurrence of antibiotic-resistant indicators in paradise coastal water of Grenada, West Indies. .

Paper presented at the 4th Congress of European Microbiologist, Federation of European Microbiological Societies (FEMS),

Geneva, Switzerland.

7.

Kotelnikova, S., Bahadoor

–Yetman, A. A.T. & Amadi, V. A., (2010). Occurrence of antibiotic-resistant fecal indicators in coastal waters of Southern Grenada.

[Electronic Version]. WINDREF Research Institute Annual Report.

pp 19-21. Retrieved 23/3/11 from http://etalk.sgu.edu/windref/pdf/AnnualReport2010.pdf

8.

Pepper, I. L., Gerba, C. P., & Brendecke, J. W. (1995). Water Microbiology. In P. Gerba, D. Brendecke, D. C. Johnson, K. L. Josephson, H. L. Bohn & J.

Tanguay (Eds.), Environmental Microbiology: A laboratory Manual (pp. 65-70). San Diego: Academic Press Inc.

9.

Farmer, J. J., 3rd, Davis, B. R., Hickman-Brenner, F. W., McWhorter, A., Huntley-Carter, G. P., Asbury, M. A., et al. (1985). Biochemical identification of new species and biogroups of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol, 21 (1), 46-76.

10.

Gross, K. C., Houghton, M. P., & Senterfit, L. B. (1975). Presumptive speciation of Streptococcus bovis and other group D streptococci from human sources by using arginine and pyruvate tests (Vol. 1, pp. 54-60).