Consultants, Urban Leadership, and the Replica City

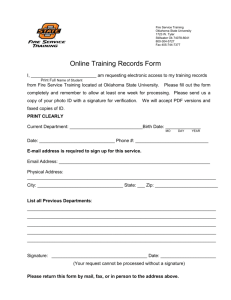

advertisement

CONSULTANTS, URBAN LEADERSHIP, AND THE REPLICA CITY Samuel T. Bassett Ph.D. Candidate Department of Political Science University of Illinois at Chicago Friday, March 13, 2015 WELCOME Thank you to everyone for attending my dissertation defense. Academic work is a team effort, and I would like to thank each of you for your support throughout this project. There are a couple of copies of the dissertation floating around, in case anyone would like to read / skim the work thus far. Please enjoy the doughnuts and coffee. MAIN FINDING Evidence suggests that the role of consultants play in local politics has fundamentally changed. In the past, urban leadership would articulate an image for the city’s future, develop an agenda (strategy) with specific projects (tactics) to accomplish these goals. Today, urban leadership articulate an image for the city’s future and articulate a general strategy, but they defer to consultants to suggest which specific projects are best suited to their goals. Local leaders determine strategy, but outsiders influence tactics. METHODS Similar methodology to great urban studies works. One city, three cases follows Dahl’s masterwork Who Governs? Narrative approach mirrors Stone’s Regime Politics and Sugrue’s Origins of the Urban Crisis Most data collection involved archival research from publicly found documents. Some informal interviews occurred inadvertently – often when requesting clarification on certain documents. People from Oklahoma City are aggressively helpful… Some personal experience informs the discussion. Some analysis involves GIS (mapping), light quantitative work (Χ2), and comparisons to similar cases. WHAT EVIDENCE? Study focuses primarily on Oklahoma City’s revitalization. Since 1993, the City of Oklahoma City has invested nearly $2,000,000,000 in infrastructure targeting commercial and residential revitalization. These investments come through publicly approved, temporary sales tax increases. Roughly 65% of Oklahoma City’s revitalization investments have focused on rebuilding school infrastructure, convention space, and a new indoor arena. Trolleys Streetcars 6% Downtown Park 7% School Infrastructu re 31% Bricktown District 11% Indoor Arena 12% Convention Space 21% THREE ISSUE AREAS This study examines three major issue areas: school infrastructure, convention space, and indoor arenas. The narrative centers on the Oklahoma City case, but evidence from other cities expands the discussion beyond a single case. Further, evidence from all central cities in metropolitan areas with over 1,000,000 residents suggests that Oklahoma City’s investments are part of a larger, national trend. OUTLINE Theoretical underpinning to the work Examination of Oklahoma City’s history Establish the way things were Three Cases (largest expenditures for revitalization) Education Infrastructure Sports Infrastructure Convention Infrastructure Highlight the role of consultants in these arenas Compare then and now Secondary findings WHY OKLAHOMA CITY? Oklahoma City’s revitalization is remarkable due to its magnitude. Throughout much of the urban crisis, Oklahoma City’s economy prospered due to high oil prices (the region’s staple industry.) In 1982, the oil bubble burst, which sent Oklahoma City into a tailspin. In 1991, Oklahoma City offered a $250,000,000 subsidy to United Airlines to lure a maintenance facility; United declined citing the city’s “low quality of life.” From 1993 through 2009, Oklahoma City voters approved four referenda increasing taxes to build amenities. By 2008, Oklahoma City appeared “recession-proof.” It only took 18 months for tax receipts to recover from the Great Recession. OKLAHOMA CITY TIMELINE Founded on April 22, 1889 through a land rush Becomes state capitol on June 11, 1910 Oklahoma City Oil Field discovered, December 4, 1928 Penn Square Bank Collapses, July 5, 1982 United Airlines declines $250M subsidy, October 1991 Voters approve the Metropolitan Area Projects, December 14, 1993 (54%) Alfred P. Murrah Building bombed, April 19, 1995 Voters approve MAPs 4 Kids, November 13, 2001 (61%) Voters approve “Big League City” referendum, March 4, 2008 (62%) Voters approve MAPs 3, December 8, 2009 (54%) OKLAHOMA CITY TIMELINE Founded on April 22, 1889 through a land rush Becomes state capitol on June 11, 1910 Oklahoma City Oil Field discovered, December 4, 1928 Penn Square Bank Collapses, July 5, 1982 United Airlines declines $250M subsidy, October 1991 Voters approve the Metropolitan Area Projects, December 14, 1993 (54%) Alfred P. Murrah Building bombed, April 19, 1995 Voters approve MAPs 4 Kids, November 13, 2001 (61%) Voters approve “Big League City” referendum, March 4, 2008 (62%) Voters approve MAPs 3, December 8, 2009 (54%) OKLAHOMA CITY’S STRATEGY SHIFT Before the Metropolitan Area Projects (MAPs), Oklahoma City’s development plan was relatively simple. Local leaders would imagine a vision for the city’s future propose a series of tactics to build that future hire experts to implement previously defined tactics During and after MAPs, the revitalization model changed. Today, leaders articulate a vision for the city’s future consult with a network of experts to determine tactics to build that future hire experts to implement these externally recommended tactics This shift yields some agenda setting power to consultants. GOVERNING AND GROWTH IN THE GLOBAL ERA URBAN COMPETITION American cities exist in a self-help world. After the demise federal urban policy, cities have been forced into an entrepreneurial stance to protect economic interests. Cities often follow one of two entrepreneurial strategies (or both) First, cities might try market incentives to attract businesses. Tax cuts and subsidies Second, cities might try to build a competitive advantage through infrastructure or work force. Amenity led growth MOBILE CAPITAL, MOBILE LABOR Towards the end of the Cold War, the globalization of capitalism and free trade fundamentally changed the marketplace at home and abroad. Capital became footloose, to the extent that companies could command and control operations across the planet from central locations. “First world” manufacturing centers could not compete with bargain basement wages in the “third world” As capital became more mobile, cities’ economic security weakened. Dynamic workers also became more mobile. The “creative class” appears to seek amenities rather than jobs. (The logic being that they are dynamic enough to work anywhere.) If this is the case, then if a community can attract enough dynamic workers, then they can create a competitive advantage to other cities and attract hypermobile capital. DECAYING LEADERSHIP Former models of urban leadership have fallen. Machines are nearly extinct Regimes appear to be less common than in previous eras Key members of regimes have been eviscerated by globalization. Another side effect of globalization is the concentration of regional companies into multinational conglomerates. Former staples of local leadership (newspaper editors, department store CEOs) no longer exist. As a whole, local leadership is often less coherent than in previous generations. Coherent leadership is a group of reconciled who can effectively “speak for” a community (and implement a long term agenda.) DECAYING LEADERSHIP As long-term coalitions declined, the ability to internally develop the expertise diminished. City building and urban revitalization require a significant amount of expertise to adequately understand what projects can positively impact a community. Local leaders are bounded by their understanding of the world. Without sustained coalitions of coherent leadership, cities are often illequipped to prescribe tactics to fulfill larger strategies. RISE OF THE EXPERT One might expect that without coherent leadership, cities would not be able to overcome the collective action problem and make large investments over time. Instead, cities continue to pour billions into downtown infrastructure, often in quasi-concerted efforts. Experts help fill the gaps left behind by decaying leadership. Local leaders are able to articulate a vision, but they often leave the details to experts who specialize in niche industries. POLICY NETWORKS Consultants exist within a policy network or advocacy coalition. These specialized communities all focus on a specific issue area, like education or arenas. Most actors agree on a baseline assumptions. Classroom technology is good for education. Luxury suites are good for arenas. Policy networks help frame arguments… even those who dissent usually end up using the dominant frame’s terminology, even if it is disadvantageous. The dominant frame allows for policy convergence across systems. There are two layers of policy networks: A layer of policy networks for each specific issue area. A larger city building network, a constellation of several issue areas. STANDARD PACKAGE OF AMENITIES A standard package of amenities has emerged across American cities. The standard package of amenities is a continually evolving list of features found in any given community of a certain size. Professional police and public water works are commonly accepted programs Major league arenas and convention spaces are older staples Exclusive schools in the central city are a newer addition The standard package of amenities signals where a city lies in the urban hierarchy. It is difficult to imagine a global city without a major airport It is difficult to imagine a regional city without an arena or convention hall. OKC AND THE STANDARD PACKAGE In the early 1990s, Oklahoma City was a major, minor city. The city’s trophy case of leisure infrastructure was deteriorating, but its position as a AAA city was hardly disputed. After the United Airlines rejection, the city decided not to refurbish its existing leisure infrastructure; instead it developed projects found in “big league” cities. These investments in the standard package of amenities helped to transform Oklahoma City from the major minor city into a minor major city. By replicating big league cities, Oklahoma City became the Replica City. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: THE REPLICA CITY MAKING NO LITTLE PLANS Oklahoma City was born in a day. Literally. In a land rush, over 10,000 settlers formed a new city in the matter of hours. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxaJY8UZxn4 Early Oklahoma City politics were extremely chaotic. Over twenty mayors served over the course of thirty years, with the several serving less than a full year. Despite this tumult, the city chartered a City Beautiful plan in 1910 – which followed other cities’ focus on boulevards and green spaces. STREETCARS AND PRIVATE GROWTH Oklahoma City’s early economy centered around regional trade, specifically moving agricultural goods (cotton and corn) to market (via the Santa Fe, Katy, or Rock Island Railroads) The city commissioned a New York businessman in 1902 to build a comprehensive streetcar system in Oklahoma City. Locals took the plan and connected several nearby cities to downtown. Real estate investors placed attractions at the end of streetcar lines. Epworth University moved from Fort Worth to the terminus of the northwest line. Epworth evolved into Oklahoma City University and part of the University of Oklahoma’s Health Sciences Center. Delmar Garden amusement park was a key destination on the southwest line. Delmar featured a zoo and professional sports. STREETCARS AND QUASI-SUBURBIA The Interurban streetcar network mirrors many larger cities’ commuter rail systems today. The longer lines connected Oklahoma City to the state capitol in Guthrie (moved to OKC in 1910), University of Central Oklahoma in Edmond, an army base in El Reno, and the University of Oklahoma in Norman. Although nearly every city in central Oklahoma dates back to the 1889 land rush, a quasi-suburban dynamic emerged as Oklahoma City became the central location in a spoke-and-hub streetcar system. Oklahoma City currently houses nearly half of the metropolitan area’s population. (615,000 compared to 1,300,000.) Other large centers lie along these lines: Norman (110,000), Edmond (85,000), Moore (55,000). OIL BOOM AND DUST In the late 1920s, Oklahoma City’s economy evolved from agriculture to oil. The Dust Bowl soiled the agriculture industry while a new pool of crude oil provided a way out for Oklahoma City Aggressive farming techniques and an irregular drought caused a series of crop failures throughout the region. Wind gusts would dislodge topsoil, leading to large “dust storms.” Meanwhile, an oil well discovered the Oklahoma City Oil Field in late 1928. As farmers fled the state to seek work in California, local oilmen rose in prominence. Local giants (Robert S. Kerr) cut their political teeth by lobbying residents to approve drilling for oil within city limits. Eventually, an oil drilled underneath the state capitol building. OIL BOOM AND DUST Despite oil income, many suffered from the economic shocks from the Great Depression and Dust Bowl. Oklahoma City’s leaders instituted a miniature New Deal, which built Will Rogers World Airport River improvements New Parks Eventually New Deal money flooded the state. Although local leaders had little control over what was built, they heavily influenced where WPA projects went. URBAN RENEWAL: THE PEI PLAN The Oklahoma City metro area emerged from the Great Depression ahead of the state with the help of oil and aeronautics. The United States built Tinker Air Force Base just east of Oklahoma City. The facility is notable as a repair station for the Air Force and Navy. Aeronautical engineering and manufacturing continue to play a large role in the local economy. In 1960, local business elites visited Pittsburgh and determined that they wanted to pursue urban renewal in Oklahoma City. The incumbent government dissented. The local newspaper owner, the head of chamber of commerce, and CEO of oil giant Kerr-McGee collaborated to install a pro-renewal council. URBAN RENEWAL: THE PEI PLAN The pro-renewal coalition chartered I.M. Pei to develop a comprehensive urban plan for downtown Oklahoma City. The Pei Plan called to raze and rebuild most of the central business district. (528 acres, nearly a square mile) Pei called for a downtown mall, downtown gardens, and a large convention center – all with the promise to land upper-middle class families downtown. With political control, the city began demolition throughout the late 1960s. By 1970, money dried up. Oklahoma City was late to the table for federal funds, and local money invested in oil. OIL BOOM AND BUST In 1973, key members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries levied an oil embargo on the United States. Oil prices skyrocketed. Wildcatting became common, where investors would drill for oil based on pure speculation – without conducting geological tests first. Oklahoma City’s financial sector flourished as the oil industry boomed. Eventually, local banks invested in wildcat wells. Oil was so valuable, and money was plentiful… so why not gamble? By the 1980s, oil prices dipped back to normal levels. In 1982, the Penn Square Bank collapsed, setting off the largest series of bank failures between the Great Depression and Great Recession. OIL BOOM AND BUST Oklahoma City’s economy was in shambles. Half of the jobs in oil disappeared. 20% of the jobs in the financial sector evaporated. Construction ground to a halt. The Pei Plan stopped dead in its tracks. HORSERACES AND HANGARS The first efforts to revive the city went back to the community’s roots: Agriculture Aeronautics During the1980s, Oklahoma City contracted the DeBartolo family to build a horseracing venue to anchor the “Adventure District.” The DeBartolos commanded a shopping and entertainment empire. The Adventure District never produced much spillover commerce In 1990, Oklahoma City (and county, and state) offered United Airlines a $250,000,000 subsidy to relocate an aircraft maintenance facility to OKC. United declined, citing Oklahoma City’s low quality of life. METROPOLITAN AREA PROJECTS Oklahoma City’s mayor Ron Norick knew that he needed to do something to save his hometown. Norick quietly took a trip to Indianapolis (the city who won the United Airlines maintenance facility) and notices a “live city.” When Norick returned to Oklahoma City, he invited local businesses, social leaders, and other layers of government to a retreat. Every group had a pet project, and nobody agreed on exactly what to do or how to do it. They knew they needed to do something, but did not know what. So they called a consultant. METROPOLITAN AREA PROJECTS In 1992, Norick asked Rick Horrow to help. Horrow had helped Miami secure financing for a downtown arena. Working with Horrow, Norick and a team of leaders commissioned a series of studies to determine which projects were feasible and which projects would be most cost effective. Eventually, consultant feedback developed a shortlist of nine projects. The total price stood at about $350,000,000. Norick took the issue to the ballot as a temporary, additional one-cent sales tax. METROPOLITAN AREA PROJECTS In December 1993, Oklahoma City voters approved MAPs. (54%) MAPs – Build Downtown Indoor Arena $87,700,000 Refurbish Myriad Convention Center $60,000,000 Improve the North Canadian River $53,500,000 Refurbish the Civic Center (Music Hall) $53,000,000 Build Downtown AAA Baseball Stadium $34,000,000 Build Bricktown Canal and green space $23,000,000 Build Downtown Library and Learning Center $21,500,000 Improve Fairground Meeting Facilities $14,000,000 Buy Rubber-Tire Decorative Trolley Busses $ 5,000,000 METROPOLITAN AREA PROJECTS In December 1993, Oklahoma City voters approved MAPs. (54%) MAPs – Build Downtown Indoor Arena $87,700,000 Refurbish Myriad Convention Center $60,000,000 Improve the North Canadian River $53,500,000 Refurbish the Civic Center (Music Hall) $53,000,000 Build Downtown AAA Baseball Stadium $34,000,000 Build Bricktown Canal and green space $23,000,000 Build Downtown Library and Learning Center $21,500,000 Improve Fairground Meeting Facilities $14,000,000 Buy Rubber-Tire Decorative Trolley Busses $ 5,000,000 METROPOLITAN AREA PROJECTS Most of the MAPs money went towards building a “live city” near the Central Business District. “Bricktown” received most of the investment. Bricktown was originally the Wholesale District, a mashup of railroad switching storage, industrial warehouses, and bulk commercial sales. By 1993, the neighborhood had decayed. In 2002, MAPs completed investments in the district. Businesses already invested in and around the new leisure space. By 2012, two-thirds of the canal-walk had spawned commerce on both sides, and residential growth emerged in the adjacent “Deep Deuce” neighborhood. MAPs 4 Kids SCHOOLS TRAILER PARK SCHOOLS In 1990, Oklahoma voters approved House Bill 1017, which mandated smaller classroom sizes by funding more teachers. This bill did not pay for infrastructure improvements to house the new classroom teachers. Many school districts rented “temporary” buildings (trailers) to hold new classes. Even wealthy suburban districts could not keep up with the new space demands imposed by the well-meaning HB 1017. EDUCATION IN OKLAHOMA CITY The City of Oklahoma City is nearly 500 square miles. Nearly three dozen independent school districts serve the same jurisdiction. When MAPs 4 Kids raised revenues, it distributed funds based on the number of students from Oklahoma City’s taxing jurisdiction served by each independent school district. EDUCATION IN OKLAHOMA CITY Voters in OKCPS also passed a bond issue to coincide with and cooperate with MAPs 4 Kids. MAPS 4 KIDS After Bricktown’s early success, local leaders turned to confront the education problem. In 2001, Mayor Kirk Humphreys proposed a new MAPs-style program. Instead of rebuilding downtown, the new funds would rebuild the city’s schools. MAPs 4 Kids raised revenue through a temporary, one-cent sales increase. Before running for mayor, Humphreys had served on the Putnam City Public Schools school board. PCPS built a new, state-of-the-art middle school during his tenure. Nearly immediately, upper-income residential development surrounded the new school. MAPs 4 Kids received public support (61%) at the ballot box. OCMAPs board hired a consultant to plan the comprehensive overhaul of Oklahoma City Public Schools after the issue passed. MAPS 4 KIDS MAPs 4 Kids framed education as a key part of the revitalization agenda. This message indicates a nuanced shift in education policy. Instead of trying to train a quality workforce in the central city, MAPs 4 Kids would give city schools equal infrastructure to its suburban counterparts. School districts allocated the vast of majority of MAPs 4 Kids funds toward building new classroom space to fill gaps from HB 1017. However, there was money left over… INFRASTRUCTURE AS A SIGNAL How school districts allocated leftover MAPs 4 Kids funds reveals a unique story about education. In Oklahoma, schools exist in a fiscal straitjacket. In order to borrow money, school districts must win a 60% majority from a public ballot. Many school districts have invested in luxuries, like interactive whiteboards, synthetic athletic turf, video scoreboards, and scurity technology. These investments started in the wealthy suburban districts, and matriculated down to the less affluent districts. Two Words: Jumbo Tron WHY SIGNALS? Assuming any credence to Tiebout’s foot-voting model (which seems plausible for education), then people sort based on quality of services and their additional costs. Unfortunately, there is no commonly accepted way to understand what makes a school good or bad. If families believe that quality education is important, and there is no reliable way to determine quality education, then families may default to signals about schools. Downs and Edelman flesh out this argument far better than I can in a short presentation. WHY SIGNALS? Public policy incentivizes investing in signals. IF Schools earn funds from high student exam performance AND Student exam scores correlate with income AND Higher income families are willing and able to move to “good” schools AND Higher income families default to interpreting signals to determine what is a “good” school THEN schools should invest in signals to attract higher income students to improve test scores and retain state funding Personal experience on a Local School Council in Chicago confirms this assertion… Why else would pre-K classrooms need SMARTBoards? OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSULTANTS The image of “good” education remains largely undefined. In the not-too-distant past, the state-of-the-art elementary school classroom included whiteboards, a television mounted to the ceiling, and chairs around tables. Today, an interactive whiteboard, portable tablet computers that accesses the cloud, and a “creative” space with untraditional furniture symbolize state-of-the art elementary education. School report cards are arguably a solution to this question, but they remain highly controversial in the media and it is unclear if they are widely used. This lack of clarity provides entrepreneurs the ability to brand their products are part of the cutting edge of education. Some items gel into what makes a classroom “good” while others turn into fads. CURIOUS CASE OF REX ELEMENTARY Oklahoma City Public Schools invested in the additional resources in the aforementioned luxuries. When OKCPS had leftover funds in the early 2010s, ex-mayor Humphreys led the charge to build a charter school in downtown Oklahoma City. Unlike other charters which have private sector patrons, the Oklahoma City Public Schools is the private partner for the charter school. The enrollment zone captures a unique part of the downtown district… it includes the neighborhoods targeted for gentrification while excluding others. ENROLLMENT BOUNDARIES Green and blue shaded areas highlight districts receiving revitalization dollars for new infrastructure. One can easily see the Rex Elementary boundary mirroring many of the other public investments. NEW AGE EXCLUSION? Metropolitan areas across the country have prestigious schools located in their central cities. This is surprising, especially due to the archetype that quality schools exist only in the suburbs. Most of these high quality schools have some exclusive component to their enrollment procedures. Chicago requires test scores, attendance, and grades to enter a “selective enrollment school”; although some preferences go to location New York City requires a high test score; although some preferences go to location Oklahoma City requires a specific location area to enter an exclusive (charter) elementary, and test scores to entre an exclusive secondary school OKC IS NOT ALONE Oklahoma City is not alone in building these new exclusive schools. Cities that control both zoning authority and the public schools are more likely to have exclusive schools. These exclusive schools are often found in gentrifying areas. This becomes more likely if the school is newer. Exclusive schools are usually whiter and wealthier than the rest of the school district. EDUCATION Evidence from Oklahoma City indicates three key trends: Education is an emerging component in the standard package of amenities, especially for residential districts located near leisure areas. Think primordial soup from Kingdon; the frame is not defined which allows outsiders easy access to append ideas to the image of “quality” education Cities use infrastructure as signals to indicate “quality” schools and encourage residential revitalization (gentrification) Exclusive enrollment practices reinforce segregation in education, which may result a two-tier education system with the same district. Big League City SPORTS INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX BUILDING THE BIG LEAGUE REPLICA One of the repeated themes throughout MAPs (1993) was the idea of building Oklahoma City into a “big league city.” The downtown ballpark maintained the city’s AAA baseball status. Minor League Baseball threatened to abandon Oklahoma City in the early 1990s without a new stadium. Instead of trying to lure an outdoor sports franchise, Oklahoma City turned to indoor sports by building an arena under MAPs 1993 The National Hockey League had teased expansion to the sunbelt throughout the early 1990s. They eventually passed on OKC in the late 1990s. College football potentially crowded out a National Football League Baseball requires high attendance at 81 home games, a large task for a small market KATRINA AND THE NOK HORNETS When Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans, the National Basketball Association’s (NBA) Hornets franchise needed a place to play. Mayor Mick Cornett contacted the NBA’s commissioner the day after the levies broke to offer room and board for the Hornets. For the next two seasons, the “NOK” Hornets played the majority of their games in Oklahoma City’s Ford Center, the downtown arena built with MAPs 1993 funds. Oklahoma City temporarily plugged into the Sports Industrial Complex, and high attendance (for an underperforming team) indicated that OKC could potentially house a struggling franchise. Oklahoma City became an exit option. SPORTS INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Professional sports is a multi-billion dollar industry. Major League Baseball draws 73,000,000 attendance annually. Television deals earn leagues $3,000,000,000 annually. The National Football League’s annual Super Bowl attracts 112,500,000 viewers. Professional sports function on a “home team” model, where franchises have geographic territories that cater to certain communities’ fans. Each professional sports league functions as a cartel – competing firms who operate as a de facto trust in order to prevent renegade competition (especially in specific markets). If a city does not adequately support (or subsidize) a team, then that franchise owners and the league may move that club to a new market. SONICSGATE The National Basketball Association’s Seattle Supersonics played in the KeyArena for most of their existence since 1967. Built to support Seattle’s Century 21 World’s Fair and mildly refurbished in the early 1990s, the KeyArena began to show its age in the late 2000s. Supersonics’ owner Howard Schultz had attempted to negotiate with the City of Seattle and State of Washington to subsidize a new arena. These efforts broke down in 2005. Upon success and familiarity with the NBA in Oklahoma City, several natural gas CEOs banded together to purchase the ailing Supersonics franchise. SONICSGATE New ownership tried to negotiate with the City of Seattle, suburbs in the area, and State of Washington for a similar subsidy. Talks failed again. The new ownership petitioned the league to move the Supersonics franchise to Oklahoma City. In 2007, the new owners petitioned the league to move the team to Oklahoma City. Team management traded star players for draft picks. Attendance in Seattle dropped, as the fix appeared to be in. BIG LEAGUE CITY While Seattle deliberated over a potential subsidy, Oklahoma City approved the “Big League City” referendum with 64% of the vote. In early 2008, Mick Cornett proposed a miniature MAPs to refurbish the downtown arena. Big League City levied a temporary, one-cent sales tax to refurbish the arena. Cornett contacted the league and prominent architects (consultants) to develop a plan to retrofit the MAPs arena into a specialized NBA space. Money from the Big League City would invest revenue from a temporary one-cent sales tax increase to follow their plan to the detail. The implicit assertion was with approving this initiative, Oklahoma City would win the Supersonics franchise. The team moved within the year. MOVING GOALPOSTS New indoor sports arenas are strikingly different from previous generations. One remarkable difference is that many new arenas hold less fans than the previous model. Instead of quantity, the new facilities support luxuries for high-paying tickets. New locker rooms, medical and training facilities help subsidize costs for sports franchises. Oklahoma City asked for consultant help to guide their arena upgrades. The refurbished arena provided more profitability than the aging, unattended KeyArena in Seattle… which helped lure the Thunder. TEAMS OVER TIME Professional sports teams relocate to new facilities. The table to the right lists all metropolitan areas with over 1,000,000 residents, ordered from the oldest arena to newest. Highlighted cities do not have an indoor professional sports team. Note that newer arenas house more teams than older arenas. THE EXIT OPTION Oklahoma City provided an exit option for the National Basketball Association. In the wake of losing the Supersonics, locals in Seattle continued to support a new arena for an NBA franchise. They targeted the Sacramento Kings franchise, the NBA team in the oldest arena. Sacramento responded by subsidizing a new downtown arena… as part of a larger revitalization program guided by consultants. Several cities serve as exit options today Kansas City Louisville Hartford and Seattle… after it builds a new arena PRISONERS DILEMMA AND SPORTS Evidence from Oklahoma City indicates two key trends: Professional sports facilities present a prisoner’s dilemma for cities. If the number of cities with major league infrastructure equals the number of professional sports franchises, then there would be no competition Sports leagues determine the number of franchises and can create an “exit option” in case cities do not provide lucrative subsidies. Consultants help city leaders fill in details that they may not normally recognize as necessary. Oklahoma City relied on consultants to both propose an arena (1993), win the funding for the arena (1993, 2008), and how to refurbish a generic space into a state-of-the-art facility (2008). CONVENTIONS AND MEETINGS CORE TO SHORE After landing the Thunder, Cornett turned to building on Oklahoma City’s “momentum,” despite the threat of the Great Recession. Oklahoma City’s planning department had commissioned a series of studies to buttress a new vision for downtown: Core to Shore. Core to Shore essentially seeks to link the central business district’s “core” to the North Canadian River’s northern “shore” – tripling the downtown footprint. PEI PLAN, PART TWO? The main components of Core to Shore are remarkable similar to the Pei Plan. Raze many buildings in the central city. Unlike Pei, though, C2S plans to level mainly residential areas. Build a large downtown greenspace and convention center to attract commerce (and eventually residents) The key problem with Core to Shore was the large costs associated with flipping working class housing and low density industrial zones into a large park and convention hall. Luckily… that temporary one-cent sales tax was about to expire. MAPS 3 MAPs 3 (2009) centered around the Core to Shore proposal. 54% of voters approved the new proposal after a viable dissenting campaign. MAPs 3 continues the temporary one-cent sales tax increase program. MAPs 3 is slated to Build new downtown convention center $250,000,000est Build central downtown park $130,000,000est Build a fixed, light-rail streetcar system $130,000,000est Improve the North Canadian River $ 60,000,000est Improve fairground meeting facilities $ 60,000,000est Build senior aquatic and wellness centers $ 50,000,000est Build sidewalks and walking trails $ 50,000,000est MAPS 3 MAPs 3 (2009) centered around the Core to Shore proposal. 54% of voters approved the new proposal after a viable dissenting campaign. MAPs 3 continues the temporary one-cent sales tax increase program. MAPs 3 is slated to Build new downtown convention center $250,000,000est Build central downtown park $130,000,000est Build a fixed, light-rail streetcar system $130,000,000est Improve the North Canadian River $ 60,000,000est Improve fairground meeting facilities $ 60,000,000est Build senior aquatic and wellness centers $ 50,000,000est Build sidewalks and walking trails $ 50,000,000est THE NEW CONVENTION CENTER Core to Shore’s centerpiece is the convention center and downtown park. The initially proposed size of the convention center is 285,000 sqft, with the intent to expand to 425,000 sqft with an attached hotel. This is a summary slide from the consulting firm Convention Sports & Leisure. The city’s plans are exactly the same as consultant recommendations. CS&L Convention Sports & Leisure enjoys an extremely large market share. Each large logo represents a consulting job in metropolitan areas with over 1,000,000 residents (of 52); small logos represent metros with over 500,000 residents (of 50). This only reflects self-advertised convention center jobs. THE SPACE RACE Cities nationwide continue to pour resources into hundreds of millions into convention space annually. The MSA without a publicly owned convention center is Bridgeport, CT; followed by New Haven, CT. Both are relatively close to Hartford, CT, which houses the Connecticut Convention Center. The table to the right lists all MSAs with over 1,000,000 residents and their convention space; sorted by the most recent expansion. THE SPACE RACE Shading reflects the most recent expansions. The majority of cities in the United States have expanded their convention center since 2000. Many cities at the top have only refurbished their convention center, which does not constitute an expansion. THE SPACE RACE Highlighted cities represent convention centers with over 1,000,000 square feet of leasable convention space. Others may advertise1,000,000 square feet; this list only includes exposition halls, ballrooms, and meeting rooms as leasable convention space. Similar to the sports prisoner’s dilemma, conventions also force cities to invest in new amenities. Unlike sports teams, conventions are not “stuck” to a home market. CLANDESTINE PUSH FOR FUNDS Oklahoma City follows the rest of the nation into the convention space race with MAPs 3. The MAPs 3 funding only covers the convention space, not an attached hotel (which was recommended by CS&L). Local leaders have turned to alternative funding methods to cover this additional cost. Shifting funds from within the MAPs 3 projects to the convention hotel Raising the citywide hotel tax Tax Increment Financing (using future property tax value increases to borrow money) Business Improvement Districts (taxing certain zones for local services/infrastructure) Each of these options reduce the visibility of urban revitalization – the unique positive presented by Oklahoma City as a case. POPULIST REVOLT? After news leaked that the convention center may absorb extra MAPs 3 dollars or new taxes might be imposed, a growing coalition against the convention center emerged. Councilman Ed Shadid became the de facto head of the movement when he challenged Cornett in 2014. Shadid attempted to unify police and fire labor unions, environmentalists, slow growth activists, and tax averse conservatives against Cornett. Cornett won reelection with 66% of the vote in 2010. Cornett’s closest challenge as from an inexperienced candidate in 2010. Two of three longtime councilmembers lost in 2010. The Fire Chief during the Oklahoma City Bombing lost to an Evangelical TEA Partier The longtime councilman from the African American community lost to a younger, community advocate candidate. CONVENTION CENTER RECAP Evidence from Oklahoma City indicates two key trends: Cities sometimes follow consultants’ recommendations to the detail Oklahoma City’s plan to build a convention center to the exact specifications of a firm’s report Cities often turn to less transparent, more complicated funding schemes to fund controversial projects In Oklahoma City’s case, redistributing MAPs 3 tax dollars met public dissent. Like other communities, Oklahoma City’s leaders have pivoted toward using TIFs and BIDs to raise revenue shielded from the public eye. POWER OVER PLACE TALE OF TWO DISTRICTS Most of Oklahoma City’s leisure attractions are found in two districts: The Adventure District Bricktown Several internally-selected ideas from the 1980s shaped the Adventure District, including a racetrack, museums, and sports complex. Bricktown was a centrally coordinated district with consultants’ help during the 1990s. ADVENTURE DISTRICT (1980S) The highlighted spaces are attractions. The red dots are restaurants. Note only a few restaurants in the district, and the extremely large amount of pavement. BRICKTOWN (1990S) The highlighted spaces are attractions. The red dots are restaurants. Note the clusters of restaurants between attractions, especially along the canal south of the ballpark. CREATING SPACES A quick comparison between the two spaces suggests that five elements may help induce commercial investment: Anchor attractions to lure visitors Introverted architecture (inward facing) to guide visitors Fortified space to foster a sense of safety Walkable routes to and from anchor attractions Manipulated traffic between anchor attractions that expose visitors to commercial opportunities QUICK COMPARISON To test the observations in Oklahoma City, the study examines the metropolitan areas with the three largest and smaller hospitality industries (using location quotients, or share of jobs in hospitality.) In these cases, the shaded zones are attractions, while red dots represent hotels. LAS VEGAS, NEVADA Casinos roughly follow the logic outlined above. ORLANDO, FLORIDA Like casinos, amusement parks roughly follow the logic above as well. NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA New Orleans may not have planned to fit this model, however the city layout does produce predicted outcomes. GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN Three zones of hotels exist in Grand Rapids, all of which are near high auto traffic areas. SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA San Jose’s lack of walkability between attractions appears to impede an economic agglomeration (spillover effect for more hotels.) MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN Hotels seem separated from the Third Ward by the interstate. Milwaukee is not a very comfortably walkable city. (see Speck) OKLAHOMA CITY REVISITED This map highlights the Bricktown district. The orange zone is a publicly subsidized department store (BassPro), which was completed in 2003. All red spaces are new commercial buildings built between 2003 and 2008. POWER OVER PLACE Although the above sampling is small, a trend emerges that how major infrastructure (attractions like arenas and convention centers) interact with the outside world impacts their ability to encourage commercial investment. Most of the evidence above suggests that details in the urban agenda may be set by consultants, the image of the city remains in the hands of local leaders. Specific geographic placement of subsidized attractions are local political issues rather than concerns for multinational actors. As a result, despite yielding some power over the agenda to consultants, local leaders retain the power over place, the ability to determine where to locate infrastructure (and therefore how it interacts with its environment and influences the local economy). FINDINGS EXPERTS SET (PART OF) THE AGENDA Local leaders articulate a vision for their cities future, and outline a general strategy. Consultants provide actionable tactics for cities to use to fulfill their goals. This is different from previous eras, likely because globalization has undermined long-term coalitions by removing key actors. LOCALS RETAIN POWER OVER PLACE Although local leaders routinely ceded some power over the agenda to consultants, they often maintain the power to geographically distribute where projects locate in a city. This power is essential, as it can impede or increase an investment’s ability to encourage economic revitalization. EVOLUTION OF A POLICY NETWORK This study examines three loosely connected issue areas, all of which with a different shape. Education is still somewhat fractious, like Kingdon’s primordial soup where actors have relatively easy access to amend the dominant frame of “good” schools. Arenas and convention centers have more stable frames, which allow for significant convergence and similarity across so many cases. Overall, a larger policy community includes all of these actors; it functions as an roughly as a advocacy coalition or policy network. Actors tend to commonly accepted goals (attracting the “creative” or upper-middle class) through publicly subsidized infrastructure investments There is no central actor governing this network, instead it is a constellation of niche-seeking actors orbits a hollow core. NEW TACTIC: FUSION REFERENDUMS Oklahoma City’s logrolling approach to urban revitalization through fusion referendums has been used in other communities. Birmingham, Alabama attempted a “MAPs Strategy” referendum in 1998. Tulsa (county), Oklahoma passed Vision 2025, a one-cent sales tax. El Paso, Texas approved a $473,000,000 bond to revitalize its downtown. All of these programs hinged on a single plebiscite election. MAPS IV? MAPs 3 expires in December 2017, and locals are already discussing what a fourth MAPs rendition would include. Leading candidates include Expanding the streetcar system Improving desirability in central city residential spaces and linking these spaces to the central business district Boosting arts nearby cultural enclaves to the central business district, possibly by building arts amphitheaters and public art Expanding the bicycle lane system, perhaps with protected bicycle lanes Increasing walkability city-wide INCREASING INCOHERENCE Discord has emerged as the city building industry grows. Certain elements of the larger policy network do not match established principles. For example, walkability studies indicate that pedestrians prefer routes with shorter blocks; convention centers and arenas nearly always exist on “superblocks”, which encompass multiple short blocks. WORK LEFT UNDONE More in-depth cases More issue areas Stronger analysis of how infrastructure interacts with their vicinity Does this apply to other cases with weakened leadership World Bank & International Monetary Fund in the industrializing world? State and subnational governments with fractured political leadership? Cities outside of the United States CONSULTANTS, URBAN LEADERSHIP, AND THE REPLICA CITY Samuel T. Bassett Ph.D. Candidate Department of Political Science University of Illinois at Chicago Friday, March 13, 2015 DISCUSSION CONSULTANTS, URBAN LEADERSHIP, AND THE REPLICA CITY Samuel T. Bassett Ph.D. Candidate Department of Political Science University of Illinois at Chicago Friday, March 13, 2015