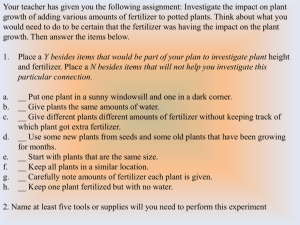

Fertilizer trees management types and maize grain yield

advertisement

Mwalwanda AB, Ajayi OC, Akinnifesi FK, Beedy T, Sileshi G, G. Chiundu 2011 Impact of Fertilizer Trees on Maize Production and Food Security in Six Districts of Malawi, World Agroforestry Centre, Lilongwe, Malawi JULY 2011 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................4 PREFACE ...............................................................................................................................................................5 ACRONYMS AND ABREVIATIONS USED ......................................................................................................6 Definition of terms ..................................................................................................................................................7 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................8 JUSTIFICATION FOR THE STUDY....................................................................................................................9 Research Gap ......................................................................................................................................................9 OBJECTIVE .......................................................................................................................................................9 METHODOLOGY ...............................................................................................................................................10 Study sites and sampling ...................................................................................................................................10 Data collection ..................................................................................................................................................11 Questionnaire survey ....................................................................................................................................11 Statistical Design and data analysis ..................................................................................................................12 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ...........................................................................................................................13 Description of respondents ...............................................................................................................................13 Maize grain yield comparison between fertilizer tree users and non users ......................................................13 Effect of plot management on maize grain yield ..............................................................................................13 Frequency of plot management types ...........................................................................................................13 Maize grain yield (kgha-1) correlations .............................................................................................................15 Fertilizer Application rate (kgha-1) ...................................................................................................................15 Fertilizer trees management types and maize grain yield .................................................................................16 Area specific comparison of Maize grain kg ha-1after selected fertilizer trees.................................................18 Maize grain yield and Gliricidia ...................................................................................................................18 Maize grain yield and Tephrosia...................................................................................................................18 Maize grain yield and Sesbania sesban .........................................................................................................18 Maize grain yield and Faidherbia albida .......................................................................................................18 Maize grain yield and Pigeon peas ...............................................................................................................19 Plot sizes versus plot management ...................................................................................................................19 Maize seed rate (kg ha-1) versus plot management type ...................................................................................20 Maize grain yield (kg ha-1) and location ...........................................................................................................20 Maize grain yield (kgha-1) disaggregated by gender of farmer and location ....................................................21 Maize grain yield (kg ha-1) disaggregated by gender of household head .........................................................23 Plot sizes disaggregated by type of plot management, location and gender of household head ......................23 Plot size and gender ......................................................................................................................................23 Land ownership and gender ..........................................................................................................................23 Respondents’ perception on impact of fertilizer trees on maize yield ..............................................................24 1|Page Respondents’ (fertilizer tree users) use of bumper maize yield ........................................................................24 Effect of previous crop on maize grain yield (kg/ha) .......................................................................................25 CONCLUSION .....................................................................................................................................................26 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ....................................................................................................................................26 REFERENCES .....................................................................................................................................................27 APPENDIX ...........................................................................................................................................................28 Appendix 1 Questionnaire for the study ...........................................................................................................28 Appendix 2 Respondents of the survey ............................................................................................................33 2|Page List of figures Figure 1 Map of Malawi showing pilot districts for AFSP ..................................................................................10 Figure 2 Possible interactions of factors determining maize yield for the study ..................................................12 Figure 3 Frequencies of plot management types ..................................................................................................14 Figure 4 Mean mineral fertilizer application (kgha-1) for conventional versus tree legume intercropping ..........15 Figure 5 Frequency of most dominant fertilizer tree management types among the fertilizer tree users .............16 Figure 6 Fertilizer trees intercropped with Maize under different management types versus plot sizes ..............17 Figure 7 Maize grain yield (kg/ha) versus common fertilizer tree management types ........................................17 Figure 8 Comparison of maize grain yield (kg/ha) across locations for different fertilizer trees .........................18 Figure 9 Average land sizes (hectares) among respondents for different plot types ............................................19 Figure 10 Maize seed rate used (kgha-1) versus plot management type ...............................................................20 Figure 13 Maize grain yield (kg/ha) in study districts as affected by type of plots ..............................................21 Figure 13 Mean plot sizes (hectares) as related to gender of farmer, type of plot management and location .....23 Figure 14 Frequencies for land ownership based on household head gender as related to location and type of plot management ...................................................................................................................................................24 Figure 15 Fertilizer tree users' prioritization of bumper maize yield ...................................................................25 Figure 16 Estimates of grain yield (kg/ha) as influenced by previous crop .........................................................25 3|Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY World Agroforestry Centre in Malawi with its partners implemented a four year (2007-2010) pilot project in Agroforestry with financial support from Irish Aid. The project known as Agroforestry Food Security Programme (AFSP) was being piloted in 11 districts spread within 8 Agricultural Development Divisions (ADDs). The overall programme purpose is to combine sound science, effective partnership and responsive scaling up approaches with informed policies that will help to increase food security and income, and improve livelihood opportunities for rural communities in Malawi, through accelerated adoption of fertilizer trees and fruit tree portfolios. The programme has been focussing on four Agroforestry options; fertilizer trees, fruit trees, fodder trees and fuel wood trees. To determine the impact of fertilizer trees on maize production and food security among its users, a study was conceived to assess comparative performance of maize (focussing on grain yield) under different species of fertilizer trees and different areas. The study also compared two broad maize production systems; conventional (use of mineral fertilizer and or unfertilized maize) with intercropping maize with fertilizer trees. This report is a synthesis of a survey results that involved randomly selected smallholder farmers from six districts in Malawi who have either been using fertilizer trees or not as intercrops with maize to boost soil fertility. The objective of the survey was to compare maize grain yields between users and non users of the fertilizer trees and also to compare the maize grain yield from maize intercropped with different types of fertilizer trees. This study was conducted during the 2009/10 growing season and involved 240 randomly selected farmers from 6 of the 11 districts in Malawi. The survey results showed that use of fertilizer trees enhanced maize grain yields over those who did not use fertilizer trees. Maize grain yields from plots intercropped with fertilizer trees were over two times more than sole cropped maize without any fertilizer. Overall, fertilizer tree users obtained 1.4 times more maize grain than non users. More grain yield translates into more food security (longer periods of household food availability) among the participating farmers as maize is a staple food crop for most Malawian households. The study also showed that users of fertilizer trees preferred pigeon pea ( Cajanus cajan) to other types of fertilizer tree species; Tephrosia (Tephrosia candida), Gliricidia (Gliricidia sepium), Sesbania (Sesbania sesban) and Faidherbia (Faidherbia albida)respectively among the dominant fertilizer trees species as intercrops with maize. However, Gliricidia sepium influenced highest maize grain yields followed by Tephrosia and Pigeon Peas. 4|Page PREFACE Through the Agroforestry Food Security Project and other similar projects implemented in earlier years in Malawi, different fertilizer tree germplasm have been provided to smallholder farmers as to popularize best bet fertilizer trees for intercropping with maize. Fertilizer trees have proven to be beneficial in improving maize productivity for resource constrained smallholder farmers. However, availability of quality germplasm has been one of the challenges in their use by smallholder farmers. World Agroforestry Centre with its partners has been championing promotion of fertilizer trees among smallholder farmers. As such, it has been providing quality germplasm of different species suitable for different agro-ecologies. This was deliberate as farmers have different preferences to a range of fertilizer tree species and also the performance of the trees varies in different agro ecologies vary. The most dominant fertilizer trees that were provided for maize intercropping to boost soil fertility were; Gliricidia sepium, Tephrosia candida, Sesbania sesban, Cajanus cajan, and Faidherbia albida. The study on impact of fertilizer trees on maize production and food security provided an opportunity to get first hand testimonies from smallholder farmers on their experiences with maize production particularly use of fertilizer trees. The study provided information on farmers’ perceptions, practices, in maize production and in soil fertility management. This report dwells more on comparisons between users of fertilizer trees and non users with respect to maize production. It provides key information on maize grain yield across the study locations differentiated by various attributes. Professor Festus Akinnifesi Regional Coordinator Southern Africa, World Agroforestry Centre 5|Page ACRONYMS AND ABREVIATIONS USED AFSP BNF CEC CISANET DAES DAHLP EPA GPS LRCD MK MoAFS MT NACAL NSO RDP WAC 6|Page Agroforestry Food Security Programme Biological Nitrogen Fixation Cation Exchange Capacity Civil Society Agriculture Network Department of Agricultural Extension Services Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development Extension Planning Area Geographical Positioning System Land Resources Conservation Centre Malawi kwacha Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Metric Tonne The National Census of Agriculture and Livestock National Statistics Office Rural Development Project World Agroforestry Centre Definition of terms Estimated maize grain yield Estimated mineral fertilizer applied Fertilizer tree users Non users 7|Page Maize grain yield harvested based on farmers’ estimation Fertilizer quantities applied estimated by farmers Farmers currently using fertilizer trees in their farms to improve soil fertility for at least one year Farmers who have never used and/or are not presently using fertilizer trees in their maize farms INTRODUCTION Maize (Zea mays) is the staple food crop in much of Malawi, and the cropping system is dominated by this crop. Maize accounts for 60% or more of cropped area in Malawi (Kumwenda et al. 1996). Food security in resource-poor households is critically linked to the productivity and sustainability of maize-based cropping system. Table 1 Relative importance of staple food in diet of Malawi (2003) Commodity Per capita consumption (kg/person/year) Daily Caloric intake (kcal/person/day) Share of caloric intake (%) Maize 133 1154 54 Cassava 89 161 7 Potato* 88 163 8 Others 647 31 Total 2125 100 *FAO data combine Potato and Sweet Potato Source: FAO, 2009a One of the identified challenges in maize production in the small holder sector is low soil fertility (Swift et al. 2007). Increasing human population has led to continuous cropping on same pieces of land often in maize monoculture without allowing regeneration of soil fertility through traditional systems such as natural bush fallows. High costs of mineral fertilizers preclude resource poor smallholder farmers from using them to replenish soil fertility. The availability of maize is so crucial that Malawi government subsidizes mineral fertilizers for small holder farming families targeting food crop production. However, the financial sustainability of the Fertilizer Input Subsidy Program is questioned due to its high cost to the national budget. However, fertilizer use alone is inadequate to alleviate the physical and biological degradation of soil. Besides, fertilizer response is very low on already degraded soils (Sileshi et al., 2009). Even if fertilizer is readily available, if the land is not managed properly (through addition of organic inputs and conservation practices) fertilizers will not be used by the crop efficiently as much of it will be lost though leaching and soil erosion. Hence, more sustainable soil fertility management practices such as fertilizer tree systems that recapitalize soil organic matter, which plays a vital role in the maintenance of healthy soil biological, physical and chemical properties. In the last 20 years the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) has been promoting Agroforestry as a sustainable farming practice for resource poor farmers in Malawi. Studies on effect of leguminous trees and herbaceous legumes on maize yields have shown positive increase over unfertilized maize and natural fallows (Sileshi et al. 2008). On station experiments on effect of leguminous trees intercropped with maize have similarly shown significant increase in maize productivity (Akinnifesi et al. 2007). World Agroforestry Centre with government partners such as Department of Agriculture Extension Services (DAES), Land Resources Conservation Department (LRCD), Department of Animal Health and Livestock Production (DAHLP, has been implementing an Agroforestry project funded and supported by Irish Aid through the Irish Embassy between 2007 and 2011. The project, Agroforestry Food Security Programme (AFSP) is implemented in eleven districts spread through eight agro ecological zones in Malawi. The project’s 8|Page goal is to improve food security, incomes and livelihood opportunities for rural communities in Malawi. The project, among other interventions focuses on the fertilizer tree system as one best bet farming practices suitable for resource constrained farming families to ameliorate degraded soils. JUSTIFICATION FOR THE STUDY Research Gap There is no doubt about high variability of maize productivity among small holder farmers owing to different levels of field management as well as variability due to different geophysical characteristics. To compare and quantify maize yield under smallholder farming situation in Malawi who have used leguminous fertilizer trees in their maize based farming systems with those that are not using fertilizer trees (hereafter called non-users) under different social economic as well as agro ecological zones can provide further evidence1 on whether or not leguminous fertilizer trees have had a positive effect on maize yield. Use of fertilizer trees in maize based farming systems under smallholder farming is low as the intervention is relatively strange to most small holder farmers in much of Malawi and inherent constraints exist associated with the cropping system under smallholder farming conditions. Among other constraints to use of fertilizer trees, smallholder farmers lack permanent land tenure rights, incidences of bush fires and browsing of trees by livestock (Ajayi and Kwesiga, 2003) after harvest of main crops such as maize. Assessment of impact of fertilizer trees on maize production and food security would generate additional information to enhance Agroforestry scaling up strategies/opportunities among smallholder farmers. The study was conceptualized to provide an opportunity of identifying and quantifying some of the multiple factors that impinge on maize productivity under Agroforestry. This being the final year of implementation of AFSP, tracking project impact on increasing food security with respect to set impact indicators will guide decisions on evaluation. Apart from a possible evaluation study to be commissioned from which comprehensive information on impact of AFSP will be collected, estimated maize yield data will provide some indirect information on early project impact on food security. We proposed to quantify the average grain yield of maize from farmers’ fields both using fertilizer tree systems and non-users. The rationale was to compare maize grain yield across the districts participating in AFSP and quantify if there is a significant improvement in maize yield attributable to fertilizer tree system. Our hypothesis is that farms using fertilizer trees will have higher maize grain yield than those who are not using. OBJECTIVE The main objective of conducting this study was to assess the impact of fertilizer trees on maize yield and household food security. The study was conceptualized to provide specific information on: The proportion of maize yield difference attributed to different fertilizer trees Profiling of households using fertilizer trees and those not using 1 Particularly under small holder agriculture sector 9|Page METHODOLOGY Study sites and sampling The study was conducted in six districts as shown in figure 1 and Appendix 2. The six districts were selected from eleven districts which are participating2 in Agroforestry Food Security Programme (AFSP). The 2009/10 growing season in Malawi was affected by widespread erratic rainfall pattern characterized by dry spells. The dry spells also caused delays in out planting of nursery based fertilizer trees such as Gliricidia sepium and Sesbania sesban. These districts were judiciously selected because there were comparatively more Agroforestry adopters who embraced fertilizer trees for periods of more than three Figure 1 Map of Malawi showing pilot districts for AFSP 2 Out of the 11 districts 10 | P a g e growing seasons and because of observed relative success of fertilizer trees growth and development despite dry spells and erratic rainfall regime experienced during the 2009/10 growing season. AFSP was also being implemented in either one or two EPAs per district in the 11 districts across the country. Twenty farmers’ fields using and ten non-user farmers’ fields were randomly3 selected per EPA. Pair-wise comparison was done for user household so that on each farm yield was compared for maize with and without fertilizer trees. The total number of respondents was 240 (Table 2 and 3). The study was designed to sample equal numbers of male and female farmers for participating and nonparticipating households but this was not possible due to insufficiency of respondents from data sources. Data collection Questionnaire survey Data was collected using a structured questionnaire (Appendix 1.) from both participating farmers, hereinafter referred to as users and non-participating farmers hereinafter referred to as non-users. These farmers were randomly selected4 from lists of 100 farmers participating and 100 non participating farmers from each EPA. There was further screening and replacement of respondents’ in the study areas where respondent was deemed unsuitable for the study. Major criteria for replaced respondents: Unavailability of respondent during time of questionnaire administration Respondents applied other organic manures to their maize crop apart from fertilizer trees Respondent could not recall estimated quantities of inputs and maize outputs from his/her field All respondents’ maize fields’ areas were measured using Geographical Positioning System (GPS) device by perimeter survey. The areas were used to calculate estimated maize grain yield (kg ha-1), estimated maize seeding rate per hectare and estimated mineral fertilizer applied (kgha-1). The questionnaire comprised the following sets of questions (see Appendix 1 for a complete copy): Basic household information Household income sources Household composition Household prioritization of yield and income from Agroforestry plots Description and history of each specific farmer’s plot Soil type (as described by farmers themselves) and fertilizer use Maize inputs used and outputs obtained from the farmers’ plots Maize grain yield harvest was estimated by the farmer including maize that was harvested green or otherwise before the final harvest. Secondary data on maize yield crop estimates and total monthly rainfall was collected from study areas for two seasons; 2008/9 and 2009/10 seasons. The study was conceptualized to show interactions as shown in figure 2 below: 3 Using random numbers, lists of 100 farmers for both fertilizer tree users and non users from each EPA were used to select the first 20 users and 10 non users farmers per EPA to be used as sample size 4 Use of random numbers 11 | P a g e multiple interactions to be studied Socio-economic factors Fertilizer Tree user Species of fertilizer tree Location (Agro ecology) Non user Maize Yield Figure 2 Possible interactions of factors determining maize yield for the study It is expected that among fertilizer tree users, there is diverse knowledge and practices in utilization of fertilizer trees that in turn may have different effects on maize production. We also expect that different agro zones would influence differently growth and development of both the fertilizer trees and maize crop. Existing socioeconomic conditions among both users and non users would also contribute to differences in abilities and potentials in management of the maize crop and leading to variations in maize yield, which would affect the socio-economic conditions of the farmers in succeeding years.. Statistical Design and data analysis The study adopted an unbalanced randomized complete block design after noting the difficulty of getting optimal or planned sample sizes for all study sites in the final data set. Data collected was analyzed using SAS (Littel, R.C. et al. 2006) for general descriptive statistics and Analysis of Variance for means of maize yields. The information from analysis only gives indication of likely impact of the fertilizer trees on maize yield because of limitations of the field sampling technique5 deployed as well as the limited years the project has been on the ground. 5 Particularly on quantities of input and outputs were estimated by respondents 12 | P a g e RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Description of respondents The study involved 240 respondents from 9 extension planning areas 6 from six districts of which 52.9% (127) were females while 47.1% (113) were males. Of the respondents, a total of 161 (67.1%) were fertilizer tree users or participating farmers and 79 (32.9%) were non fertilizer tree users. A majority of households representing 81.7% (196) were male-headed while 18.3% (44) were female-headed. The households’ size had a mode of 6 and mean of 5.91. The level of education among the interviewees was generally primary school level (67.9%). Most of the sampled households (87.9%) received trainings related to Agroforestry and farming practices and only 12.1% did not receive such training. A majority of respondents (79.6%) have non-farm income as in contrast with (20.4%) households who did not have any non-farm income. Maize grain yield comparison between fertilizer tree users and non users The results showed very significant differences (p<0.0001) in maize grain yield between fertilizer tree users and non users. Overall the mean maize grain yield from fertilizer tree users was 2481 kg ha-1 while from non users was 1723 kg ha-1. Fertilizer tree users therefore had 1.4 times more maize grain translating into more months of food availability (food security) at the household. Effect of plot management on maize grain yield The study further subdivided the two groups of farmers interviewed (fertilizer tree users and non users) into four general cultural practices7 for maize production, these: maize without fertilizer application8, maize with fertilizer application, maize intercropped with fertilizer trees and maize with combined use of mineral fertilizers and fertilizer trees as intercrops. This study compared means of total maize yield9 per hectare for mean maize grain yield across all observations. These means were very highly significant (p<0.0001) across all observations attributed to type of cultural practices for maize production. There were also very significant differences among means of total maize grain yield for each of the general cultural practices (Table 2). Frequency of plot management types The commonest maize plot management type among respondents was conventional type of maize production (46%), where farmers rely on mineral fertilizers, followed by combined use of mineral fertilizers and fertilizer trees (30%), intercropping maize with fertilizer trees (16%) and the least common maize plot management type was unfertilized maize (8%). The relatively higher percentage of farmers opting for conventional maize growing over intercropping with leguminous fertilizer trees underlines the importance farmers attach to mineral fertilizers and that despite the cost, they find mineral fertilizer to be more convenient. This study has shown that there are relatively fewer farmers practicing Agroforestry in form of intercropping maize with fertilizer trees. Despite evidence showing that Agroforestry is a sustainable farming system, many farmers still practice conventional farming. Similar observations were made by Snapp et al (1998) who noted challenges farmers face with Agroforestry as including; high establishment costs, resource competition and delayed benefits (Snapp et al. 1998). 6 In Thyolo, two EPAs (Thyolo Central and Matapwata) were combined as each could not provide adequate number of required respondents Common maize production systems among the respondents 8 Or negligible amount applied (≤5kgha-1) 9 The respondents’ estimated sum of all maize harvested including green maize 7 13 | P a g e Maize alone 8% Maize + Fertilizer + Fert. trees 30% Maize + Fertilizer 46% Maize + fertilizer trees 16% Figure 3 Frequencies of plot management types Table 2 Comparison of means of total maize yield at harvest (kg ha-1) Plot Management Frequency Mean Standard Error Maize without fertilizer 36 1322 220.33 Maize with fertilizer 213 1736 118.95 Maize with fertilizer trees 72 3053 359.8 Maize with fertilizer trees + fertilizer 135 3071 264.31 The yield difference between maize with fertilizer trees and Maize with both fertilizer trees and mineral fertilizer was negligible indicating fertilizer trees had stronger influence over mineral fertilizers in contributing to maize yield. Maize grain yield from plots with fertilizer trees had 1.8 times more yield than maize from plots that only received mineral fertilizer. Under ideal10 or full mineral fertilizer application this may not be the case as maize grain yield after full fertilizer application gives more maize grain yield than where only coppicing fertilizer trees are used as noted in a study of comparative literature indicating evidence of impact of green fertilizers on maize production by Sileshi et al. (2009). In their study, the yield difference between unfertilized maize and maize with full fertilizer application was higher than yield difference between maize with coppicing fertilizer trees and maize that was unfertilized. However, under resource-poor smallholder farming scenario, variability of field management and in particular general sub optimal rates of fertilizer application may give comparatively lower response to mineral fertilizer application. Under such conditions, soil fertility improvement through fertilizer trees is likely to provide a higher net increase in nutrients additions from mineralization of high quality biomass, nutrient recycling from lower soil depths that maize roots may otherwise not access as well as biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) that translates into higher maize productivity. Apart from BNF, fertilizer trees also improve soil organic matter that in turn improves moisture and nutrient holding capacity of soils. In our study, mean maize yield from unfertilized maize was half that from maize intercropped with fertilizer trees. This is consistent with results from a study by Sileshi et al. (1999) where maize yields were higher with intercropping with coppicing green manure legume crops than from unfertilized maize. The results showed high variability (standard errors) of mean maize grain yield for maize intercropped with fertilizer trees. This could be because there was wide variability of management of the trees, variability in growth and development of the trees in different districts that in turn had different impacts on maize growth 10 Under small holder conditions mineral fertilizer applications is generally sub-optimal (Waddington, S.R. and Heisey, P.W. 1997) 14 | P a g e and development. As with conventional maize production, mineral fertilizers application to maize intercropped with fertilizer trees showed reduced yield variability. Maize grain yield (kgha-1) correlations The following variables had positive correlations at P<0.0001 with overall maize grain yields per hectare as follows: Table 3 Maize grain yield and correlations Factor Rate of fertilizer application Rate of maize seed application Green maize harvested Maize grain yield at harvest (discounting green maize) Sample size 455 456 456 456 % Correlation 23 46.6 36.7 97 There was also a negative correlation (29.7%) between maize grain yield and plot size. This could be because of low productivity in smallholder production system. As land size increases, the efficiency in use of inputs such labour and mineral fertilizers were reduced. The average land holding was 0.28 ha with the individual household’s maximum and minimum land holding sizes of 3.2 ha and 0.00089 ha respectively. Fertilizer Application rate (kgha-1) Mineral fertilizer application kg/ha There were very significant (p<0.0001) differences among means of quantities of estimated mineral fertilizers applied to maize in all observations. This study showed that overall farmers made substantial savings (53.2%) on quantities of mineral fertilizers when they intercropped maize with fertilizer trees as they substantially reduced quantities of mineral fertilizer applied unlike under conventional system 11. This gives evidence that farmers are aware of the positive contribution of fertilizer trees to nutrient needs of their maize crop. 80 75.79 70 60 50 35.47 40 30 20 10 0 Maize + Fertilizer Maize + Fertilizer + Fert. trees Comparison of conventional and intercropping system in fertilizer use Figure 4 Mean mineral fertilizer application (kgha-1) for conventional versus tree legume intercropping 11 Monoculture maize that mainly rely on mineral fertilizers 15 | P a g e Fertilizer trees management types and maize grain yield The study revealed that three fertilizer trees species are the most predominant among the five types of fertilizer trees that were intercropped with maize across all the six study districts among sampled adopter farmers (Table 4 and figure 5). These are Pigeon peas, Tephrosia and Gliricidia. Pigeon pea was the most favoured possibly because it has multiple benefits such as food, cash crop apart from its organic fertilizers. Table 5 Fertilizer tree management types with mean plot sizes and grain yield (kgha-1) Fertilizer tree management Frequency Plot Size (ha) Maize kg/ha Gliricidia No fertilizer 15 0.12563 3153.82 Gliricidia + fertilizer 27 0.09467 3569.66 Tephrosia No fertilizer 21 0.14752 3170.31 Tephrosia + fertilizer 27 0.125 2887.09 Sesbania No fertilizer 5 0.12306 2163.91 Sesbania + fertilizer 4 0.10997 4784.99 Faidherbia No fertilizer 1 0.18227 548.62 Faidherbia + fertilizer 6 0.50651 1872.49 Pigeon pea No fertilizer 22 0.15275 2273.91 Pigeon pea + fertilizer 52 0.19173 2711.42 Others No fertilizer 2 0.09211 1160.13 Others + fertilizer 5 0.22482 2440.23 Gliricidia + Pigeon pea + No fertilizer 2 0.07463 11758.48 Gliricidia + Pigeon pea + fertilizer 2 0.05349 9255.34 Tephrosia + Pigeon pea + fertilizer 6 0.22547 1985.99 Gliricidia + Tephrosia + fertilizer 3 0.31895 4124.39 Tephrosia + Pigeon pea + No fertilizer 2 0.08475 6636.71 Tephrosia + Others + No fertilizer 1 0.18375 2503.43 Gliricidia + Faidherbia + fertilizer 2 0.2001 1775.32 Pigeon pea + Sesbania + No fertilizer 1 0.1349 2816.9 Tephrosia + Sesbania + fertilizer 1 0.16803 6427.61 60 Frequency 50 40 30 20 10 0 Gliricidia No fertilizer Gliricidia + Tephrosia No Tephrosia + Pigeon pea Pigeon pea + fertilizer fertilizer fertilizer No fertilizer fertilizer Dominant maize + fertilizer tree intercropping systems Figure 5 Frequency of most dominant fertilizer tree management types among the fertilizer tree users 16 | P a g e Mean plot sizes (hectare) The study also noted that among the fertilizer trees, Pigeon pea intercropped with maize had larger plot sizes allocated than Tephrosia and Gliricidia intercropped with maize respectively (Figure 6). This further confirms the greater importance farmers in this study attach to Pigeon peas as a fertilizer tree. 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 Gliricidia No Gliricidia + Tephrosia Tephrosia + Pigeon pea Pigeon pea + fertilizer fertilizer No fertilizer fertilizer No fertilizer fertilizer Dominant maize + fertilizer tree intercropping systems Figure 6 Fertilizer trees intercropped with Maize under different management types versus plot sizes It was also interesting to note from the study that despite the farmers’ preference of Pigeon pea over the other fertilizer trees, Gliricidia sepium was outstanding in influencing higher maize grain yields followed by Tephrosia and Pigeon peas (Figure 7). Application of mineral fertilizers to intercropped maize with fertilizer trees improve maize grain yields slightly particularly for farmers who used Gliricidia and Pigeon peas across the locations (figures 7-8).This may be attributed to insignificant amounts as well as highly variable amounts used of mineral fertilizers applied among the farmers who used fertilizer trees. Maize grain yield (kg/ha 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Gliricidia No fertilizer Gliricidia + fertilizer Tephrosia No fertilizer Tephrosia + Pigeon pea No Pigeon pea + fertilizer fertilizer fertilizer Dominant maize + fertilizer tree intercropping systems Figure 7 Maize grain yield (kg/ha) versus common fertilizer tree management types 17 | P a g e Lilongwe Mzimba Machinga Thyolo Mulanje Salima 10000 9000 Maize grain yield (kg/ha) 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 GliricidiaNo fertilizer With fertilizer Tephrosia No fertilizer With fertilizer Pigeon peas No fertilizer With fertilizer SesbaniaNo fertilizer With fertilizer Fertilizer trees management Figure 8 Comparison of maize grain yield (kg/ha) across locations for different fertilizer trees Area specific comparison of Maize grain kg ha-1after selected fertilizer trees Maize grain yield and Gliricidia The study revealed that maize grain yields from plots with Gliricidia sepium without mineral fertilizers were highest in Thyolo and Mulanje but where fertilizers were added, Maize grain yield was highest in Salima followed by Lilongwe (figure 8). Maize grain yield and Tephrosia Maize grain yields from Tephrosia plots without mineral fertilizer were variable. Salima had highest grain yields followed by Mulanje and Thyolo respectively. However, where mineral fertilizers were applied the grain yield were somewhat stable (small variation) across the study sites with Mzimba producing higher maize grain yield followed by Lilongwe and Salima (figure 8). Maize grain yield and Sesbania sesban Generally most farmers who intercropped their maize with Sesbania sesban applied mineral fertilizers except for two farmers in Lilongwe. Maize grain yields from plots intercropped with Sesbania were highest in Salima although it was only a single farmer followed by Lilongwe (figure 8). Maize grain yield and Faidherbia albida The study noted that generally maize grain yields were comparatively lower under plots with Faidherbia albida. Grain yields were highest from Salima followed by Mzimba district (figure 8). 18 | P a g e Faidherbia No fertilizer With fertilizer Maize grain yield and Pigeon peas The study found that intra district variation in maize grain yield was not very wide between non fertilized and fertilized plots intercropped with Pigeon peas. However, grain yields were markedly higher in Salima followed by Lilongwe (figure 8). Plot sizes versus plot management There were very significant differences (p<0.0001) across all respondents in average plot sizes for different maize plot management types. Conventional system of maize production were allocated more land (≥0.35 hectares) compared to either intercropped system with fertilizer trees or a system of combining both fertilizer trees and mineral fertilizers (≥0.15 hectares). Since respondents were smallholder farmers, more land allocation to maize is a rational choice to maximize their maize food output. The dominance of the conventional production of maize may also be a reflection of previous overemphasis by agricultural extension agents on use of mineral fertilizers and hybrid seed for maize production (Mtawali, 1993) Maize + Fertilizer + Fert. trees 16% Maize + fertilizer trees 14% Maize alone 34% Maize + Fertilizer 36% Figure 9 Average land sizes (hectares) among respondents for different plot types 19 | P a g e Maize seed rate (kg ha-1) versus plot management type There were very significant differences (p<0.0001) across all respondents in means of maize seed rate (kg/ha) and seed rate very significantly influenced maize grain yield (kgha-1). Except for maize plots that received mineral fertilizers, the other plot management types had relatively very high estimated seed rate applications possibly due to resupplying of seed due to failure to germinate or establish under zero fertilizer level or where there was intercropping with fertilizer trees. Farmers probably had preferential treatment on their plots with fertilized maize over other plot management types. Better crop management may also have entailed better optimization and selection of seed input type. It should also be noted that the seed rates were based respondents estimations as such there was possibility of either over estimation or otherwise. 60 maize seed rate (kg/ha) 50 40 30 20 10 0 Maize alone Maize + Fertilizer Maize + fertilizer trees Maize + Fertilizer + Fert. trees Maize plot manegement type Figure 10 Maize seed rate used (kgha-1) versus plot management type Maize grain yield (kg ha-1) and location Maize grain yield (kg ha-1) variations were less with mineral fertilizer applications across the six locations but variation was marked where maize was sole cropped without fertilizer, intercropped with fertilizer trees or combination with mineral fertilizers. This may be partly due to a) diversity of agronomic practices such planting patterns, times, maize seed selection, etc and b) variations in fertilizer tree performance across the locations due to genotypic variations in adaptability to geophysical conditions. In this study there were no farmers who practiced maize monoculture without fertilizer in Thyolo perhaps underlying the severe land pressure by humans due to high population density that makes intercropping as the best choice in maximizing productivity of land. Figure 11 shows the general picture of maize grain yield in the study districts as affected by type of plot management. 20 | P a g e Maize alone Maize + mineral fertilizer Maize + fertilizer trees Maize + fertilizer trees + mineral fertilizer 4500 4000 Maize grain yield (kg/ha) 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Lilongwe Mzimba Machinga Thyolo Mulanje Maize grain yield (kg/ha) in different districts as affected by type of plots District Figure 11 Maize grain yield (kg/ha) in study districts as affected by type of plots Maize grain yield (kgha-1) disaggregated by gender of farmer and location In general, maize grain yield was higher for male farmers than female farmers for all the four types of plot management (figure 13). This may be because of resource entitlement disparities between male and female farmers where generally male farmers dominate in controlling financial resources as well as land which directly influence production abilities. 21 | P a g e Salima Maize alone Maize +mineral fertilizer Maize + fertilizer trees Maize + fertilizer trees + mineral fertilizer 6000 5000 maize grain yield (kg/ha) 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 District and gender of farmer Figure 12 Mean grain yield (kg/ha) as influenced by type of plot management, gender of farmer and location 22 | P a g e Maize grain yield (kg ha-1) disaggregated by gender of household head There were no consistent patterns in maize grain yield attributed to gender of household head for three plot management types except where mineral fertilizers only was applied. In plots where mineral fertilizers only were applied, maize grain yield was generally higher for male headed households than female headed households. This may be because such male headed households tend to have at their disposal more resources for production such as labour and opportunities for non farm income that enhances efficiency of maize or crop production. Plot sizes disaggregated by type of plot management, location and gender of household head Plot size and gender The survey results show that male headed households generally have larger pieces of land than female headed households for all plot management types across all the sites although the distinction in plot sizes based on gender was not very clear for maize plots with both fertilizer trees and mineral fertilizers (figure 14). Land ownership and gender The study also observed male domination in land ownership across all the study areas and for all for all plot management types (figure 15). Male dominion was very apparent in Mzimba and Lilongwe districts. In the former, the status perhaps reflects patriarchal culture prevalent in the area. However disparity in land ownership between male and female headed households is minimal for Mulanje and Thyolo districts perhaps underlying a matriarchal society predominant in the two districts. Our findings are also consistent with NSO (2007) that reported dominion of males over females in both land sizes owned and number of plots owned under smallholder sector being operated by male operators as household heads. Maize alone Maize +mineral fertilizer Maize + fertilizer trees Maize + fertilizer trees + mineral fertilizer 1.8 1.6 Mean plot sizes (hectare) 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 District and gender of farmer Figure 13 Mean plot sizes (hectares) as related to gender of farmer, type of plot management and location 23 | P a g e Maize alone Maize +mineral fertilizer Maize + fertilizer trees Maize + fertilizer trees + mineral fertilizer 60 Frequency of land ownership 50 40 30 20 10 0 District and household head gender Figure 14 Frequencies for land ownership for household head gender as related to location and type of plot management Respondents’ perception on impact of fertilizer trees on maize yield It was interesting to note that a majority of fertilizer tree users (97%) gave a positive perception of impact of the fertilizer trees on maize yield. This was based on pair-wise comparisons12 over the period of adoption of the fertilizer trees. Respondents’ (fertilizer tree users) use of bumper maize yield Respondents’ major use of bumper harvest from maize intercropped with fertilizer trees was to ensure household had adequate food reserves. This is based on summation of two related categories of responses. These; 22% of respondents retained the bumper harvest for later consumption and 30% of respondents consumed more maize. Household food security is the overriding rationale for keeping surplus maize grain yield. Extra maize yield also act as cash income source (25% of respondents) and therefore augmented household income. 12 Each fertilizer tree user compared maize yield between sole cropped and intercropped maize with fertilizer trees 24 | P a g e Other uses of extra cash 10% Exchanged for farm inputs (slashers, hoes, fertilizer etc) 13% Sold to obtain cash 25% Eat more often than before 30% Food lasts longer 22% Figure 15 Fertilizer tree users' prioritization of bumper maize yield Effect of previous crop on maize grain yield (kg/ha) The results show that maize after Tobacco gave highest grain yield. Most farmers apply mineral fertilizers to Tobacco hence there is residual effect of the mineral fertilizers on maize. 5000 4500 Maize Yield kg/ha 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Maize Groundnuts Cassava Tobacco Pigeon peas Vegetables Beans Previous fallow type Figure 16 Estimates of grain yield (kg/ha) as influenced by previous crop 25 | P a g e Millet Other Natural fallow Not applicable CONCLUSION Under smallholder farming system, fertilizer trees have been perceived in this study to substantially enhance maize yield and therefore positively improve household food security among farmers who intercrop their maize crop with them. Under smallholder farming situation where access of mineral fertilizers is a challenge because of cost, use of fertilizer trees offers alternative soil improving organic fertilizer and sustainable production system. Fertilizer tree use is still very limited among smallholder farmers in Malawi despite the obvious benefits in yield improvement. Even among those few farmers who have embraced the fertilizer trees in their maize based farms, the proportion of maize crop intercropped with the fertilizer trees is negligible. It is recommended that further studies on farm use of fertilizer trees among smallholder farmers be done focusing on underlying challenges associated with utilization of the fertilizer trees and also to have more empirical studies on effects on soils as well as maize performance. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We sincerely thank the Irish Aid for the financial support in implementing the Agroforestry Food Security Programme. We would like to thank all our partners for the good collaboration during implementation of the project. We thank the farmers who allowed our team of enumerators to interview them to share their experiences of onfarm maize production with or without fertilizer trees and other related information. I am also grateful to the enumerators, data entry clerks, government field extension workers who supported the survey in many ways. I am very indebted to the team of ICRAF Malawi scientists who provided their invaluable input in analyzing the data collected and subsequently in the write up of the research report. 26 | P a g e REFERENCES Ajayi, O.C. and Kwesiga, F., 2003. Implications of local policies and institutions on the adoption of improved fallows in eastern Zambia. In: Agroforestry Systems, 59: pp 327-336. Akinnifesi, F., W. Makumba, G. Sileshi, O. Ajayi, and D. Mweta. 2007. Synergistic effect of inorganic N and P fertilizers and organic inputs from Gliricidia sepium on productivity of intercropped maize in Southern Malawi. Plant and Soil 294:203-217. FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2009a. FAO Food balance sheet. http://faostat.fao.org/site/368/default.aspx#ancor. Littel, R.C., G.A. Milliken, W.W. Stroup, R.D. Wolfinger, and O. Schabenberger. 2006. SAS for Mixed Models, Second Edition SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. Kumwenda, JD.T., S.R. Waddington, S.S. Snapp, R.B. Jones, and M.J. Blackie. 1996. Soil Fertility Management Research for the Maize Cropping Systems of Smallholders in Southern Africa: A Review. NRG Paper 96-02. Mexico, D.F.: CIMMYT Mtawali, K.M. 1993. Current status of and reform proposals for agriculture: Malawi. In: Agricultural reforms and regional market integration in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, ed. A. Valdes and K. MuirLeresche. Washington, D.C. International Food Policy Research Institute. National Statistics Office, 2007. The National Census of Agriculture and Livestock. School of oriental and African Studies (SOAS), Wadonda Consult, Oversees Development Institute and Michigan State University. 2008. Evaluation of the 2006/7 Agricultural Input Supply Programme, Malawi: Final Report. London School of Oriental and African Studies; March 2008. Sileshi G., Akinnifesi F.K., Ajayi O.C., Place F. (2008) Meta-analysis of maize yield response to planted fallow and green manure legumes in sub-Saharan Africa. Plant and Soil 307:1-19. Sileshi G, Akinnifesi FK, Ajayi OC, Place F. 2009. Evidence for impact of green fertilizers on maize production in sub-saharan Africa: a meta-analysis. ICRAF Occasional Paper. Snapp, S.S. , Mafongoya, P.L. , and Waddington , S. 1998. Organic Matter Technologies for Integrated nutrient Management in smallholder cropping systems of southern Africa. In: Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. pp185-200. Swift M.J., Shepherd K.D. (Eds) 2007. Saving Africs's Soils: Science and Technology for Improved Soil Management in Africa. Nairobi: World Agroforestry Centre. Waddington, S.R., Heisey, P.W., 1997. Meeting the nitrogen requirements of maize grown by resource-poor farmers in southern Africa by integrating varieties, fertilizer use, crop Management and policies. In: Edmeades, G.O., BaÈnziger, M.,Mickelson, H.R., PenÄaValdivia, C.B. (Eds.), Developing Drought and Low N-Tolerant Maize. Proc. Symp., CIMMYT, El BataÂn, Texcoco, Mexico D.F Mexico, 25±29 March 1996. 27 | P a g e APPENDIX Appendix 1 Questionnaire for the study Name of farmer: ___________ Identification number: ________________ Village: ___________________ Section:____________________________ EPA: _________________________ District: ____________________________ Date of interview: Day ____Month_____ Name of enumerator________________ Section A: (complete this section once for each household) A1. Basic household information Information required Response Code 1=Agroforestry farmer 2=Non agroforestry farmer a. Type of farmer b. Total number of years of experience with fertilizer trees AFSP:________ CIDA:________ TARGET :____ Other:________ c. Have you had any training on agroforestry or other related agricultural practices in the last 3-4 years? 1st: __________ d. Please name them (rank with the most important 2nd : ________ 3rd: first) __________ 4th: __________ e. Gender of interviewee f. What is the gender of the head of your household Write the number of years for each project 1=No 2=Yes 1=Agroforestry 2=Conservation agriculture 3=Compost making 4=Manure farming 5=Soil & water conservation 1=Female 2=Male 1=Female 2=Male g. Age of farmer (actual years) 1=None at all 2=Primary school 3=Secondary school 4=Post secondary 5=Others (specify) h. Level of formal education of farmer A2. Household income sources a. Do you have any type of non-farm income? Type of off-farm income b. Tell me these sources or off-farm Ganyu income Small-scale business/trading 28 | P a g e 1=No 2=Yes Average income from this source per month (MK) Artisans- bicycle & radio repairs, brick making, mat etc Seasonal contract Remittance from outside A3. Household Demography What is the total number of persons in your household? ___________________________ How many of these are male and female? Male: _______ Female: _____ Please tell me the composition of these individuals based on the following table Category Number each category in Fully Schooling engaged in fulltime farm work Too young/ too old to participate in farm work or school a. Male b. Female A4. Use of extra maize yield or income from AF plots Type of information Response Code 1=Yield from AF plot is higher a. Please compare the maize yield from your 2= Yield from AF plot is lower AF and non- plots? 3=Same / No difference b. In your opinion, what do you think is responsible for this? c. Who makes the decision on how to use the extra maize yield or income obtained from AF plots? d. What do you do with the extra maize yield and/or cash obtained in AF plots? 29 | P a g e 1=Soil fertility is better in AF plot 2=Soil moisture is better in AF plot 3=Weeds are less in AF plots 4=Due to the type of seeds planted 5=.. 6=… 1=Myself 2=My husband 3=My wife 4=The Chief 5=… 1=Sold to obtain cash 2=Eat more often than before 3=Gave out to friends and relations 4=Food lasts longer 5=Exchanged for household items (clothes, bowls, etc) 6=Exchanged for farm inputs (slashers, hoes, fertilizer, etc) 7=Pay medical bills 8=Pay children school fees /uniforms 9=Buy or develop plot of land 10-Renovate existing family house 11=Marry new spouse 12=Buy transport (bicycles, bike, etc) 13=Buy new clothes for self or family Section B: (complete this section for EACH PLOT cultivated by the household) B1. Description and history of each specific plot Name of farmer: ____________________ Identification number: ________________ Plot code: _________________________ Type of information Response Code a. Description of plot Maize with…. 1=Fertilizer tree only 2=Fertilizer tree + mineral fertilizer 3=Mineral fertilizer only 4=No fertilization at all b. What is the size of this plot? Measure field with GPS and give answer in square meters c. Type of fertilizer trees planted in the plot 10=Gliricidia, NO fertilizer 11=Gliricidia + fertilizer 20=Tephrosia, NO fert 21=Tephrosia + fert 30=Sesbania, NO fert 31=Sesbania + fertilizer 40=Faidherbia, NO fert 41=Faidherbia + fert 50=Pigeon pea, NO fert 51=Pigeon pea + fert 60=Others, NO fert 61=Others +fert Plot 1 Plot 2 Plot 3 Plot 4 d. Did you apply mineral fertilizer in this fertilizer tree plot? e. Which year did you establish the fertilizer tree plot? f. Which year did you incorporate biomass into the plot? g. How many times did you incorporate biomass in this plot during the season? 1=No 2=Yes Put the year 2008/09, etc directly, 2001/02, Put the year directly, 2001, 2008, etc 1st biomass: _____ h. When did you make the biomass incorporations in this plot? 1=January 2=Feb 3=March 4=April 5=May 6=June 2nd biomass: _____ Indicate the number of years between establishment and incorporation of biomass i. How old were the trees before incorporating them in this Plot 1 Plot 2 Plot 2 Plot 4 plot? j. What is the situation of the growth (quantity & quality of biomass) when you were incorporating them? k. What crop(s) did you plant in 30 | P a g e 7=July 8=August 9=Sept 10=Oct 11=Nov 12=Dec 1=Very good/Good 2=Fair / Average 3=Poor/bad Crop1 Plot 1 Plot 2 Plot 3 Plot 4 1=Maize 10=vegetables the plot in the previous year before you embarked upon establishing fertilizer trees in the plot? 2=Groundnut 3=Rice 4=Cassava 5=Tobacco 6=Sunflower 7=Cotton 8=Pigeon pea 9=Banana Crop 2 Crop 3 11=sweet potato 12=Beans 13=Sorghum 14=Millet 15=Irish potato 16=Pumpkin 17=beans 18=other crops Crop4 B2. Soil type and use of fertilizer Type of information Response Plot 1 Plot 2 Code Plot 3 Plot 4 a. What is the dominant soil type in your plot? 1= Poor 2= Average 3= Good b. What is the fertility status of the soils in your plot? c. Did you apply mineral fertilizer in this plot during the season? d. How many times did you apply the mineral fertilizer in the plot? 1=No 2=Yes 1=All applied at once 2=Split and applied on two different times (Basal and top dressing) 1=Compound NPK 2=Urea 3=CAN 4=Others (specify) ____________________ e. What is the type of fertilizer used? f. What is the quantity of fertilizer applied? B3. Maize inputs used and output obtained from the plot Type of information Response a. What is the estimated size of your Plot 1 Plot 2 Plot 3 plot? b. What type of maize seeds did you plant? c. What is the source of maize seed that you planted? d. Was the seed mentioned in (b) planted in the entire plot or part of the plot only? e. What is the quantity of maize seeds planted in the plot? f. When did you plant the maize seeds? 31 | P a g e 1=Sandy soil (Mchenga) 2= Red soil (Katondo) 3= Dark clayey soil (Makande) 4= Others Convert all quantity given in local units to Kg equivalents Code Plot 4 Note the area/size given by farmers and convert to hectare 1=Local 2=Improved/hybrid 3=Composite 1=Recycled 2=Purchase 3=Subsidy 4=Gift 1=Entire plot 2=A section of the plot only Convert response to Kg 1=Late November 2=Early December 3=Late December 4=Early January 5=Late January 6=Early February g. Did it become necessary to replant your plot with maize e.g., due to mid-season drought? h. How many times did you weed the plot during the season? i. What is the total quantity of maize that farmers estimated that s/he obtained from this plot? j. What is the quantity of maize that you harvested green (i.e. before the maize is dried) k. What is the total amount of maize grain harvested from this plot this year? l. Based on your estimation, how many months will this amount of maize be able to feed all the members of your household? 1=No 2=Yes Indicate the number of times Get the quantity from farmers and convert to Kg Get the quantity from farmers and convert to Kg Important: Get the weight in local units (bags, ox carts, etc) and later convert to KG Obtain the estimate from the farmer Plot 1 Plot 2 Plot 3 Plot 4 Give the estimated value of this in MK or provide the quantity and convert to MK value Wood m. List ALL the other types of nonmaize grain products that you got from this plot Mushroom Seeds 32 | P a g e Appendix 2 Respondents of the survey Table 1 Number of respondents of the survey disaggregated by location and gender of household head District Lilongwe EPA Chigonthi Gender of Household head Female Emsizini 4 19 7 26 3 1 4 18 8 26 3 1 4 17 9 26 4 2 6 16 8 24 0 1 1 20 9 29 Female 5 1 6 Male 9 7 16 Female 2 0 2 Male 4 2 6 Female 5 5 10 15 5 20 6 1 7 14 9 23 161 79 240 Female Female Male Zombwe Female Male Machinga Nanyumbu Female Male Thyolo Matapwata Thyolo centre Mulanje Thuchira Male Salima Tembwe Female Male Grand totals 33 | P a g e Nonadopter 3 Male Mzimba Adopter Grand Total 1 Male Mpingu Type of farmer Table 2 Number of respondents of the survey disaggregated by location and gender of Interviewee District Lilongwe EPA Chigonthi Mpingu Mzimba Emsizini Zombwe Machinga Nanyumbu Gender of Household head Female Matapwata Thyolo centre Mulanje Thuchira Tembwe 13 Male 10 4 14 Female 13 4 17 Male 11 5 16 6 5 11 Male 13 4 17 Female 14 5 19 Male 7 6 13 Female 9 6 15 11 4 15 Female 6 6 12 Male 4 0 4 Female 8 2 10 Male 2 2 4 11 6 17 9 4 13 17 7 24 3 3 6 161 79 240 Female Female Female Male Grand totals 34 | P a g e Nonadopter 6 Male Salima Adopter Grand Total 7 Male Thyolo Type of farmer