Mortality audit

advertisement

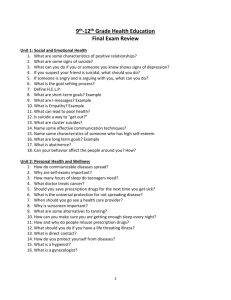

Mortality audit BHIVA Audit and Standards SubCommittee Participating centres Responses were received from 133 clinical centres: 80% outside the NHS London region, 19% in the London region, 1% unstated. 19% serving 1-50 HIV patients, 23% 51-100, 20% 101-200, 21% 201-500, 17% more than 500 patients. 40 centres reported no deaths among their adult HIV patients in the preceding year, including 52% of those serving 100 or fewer patients. Information on deaths Respondents were asked how they find out when HIV patients under their care die in the community (more than one answer was allowed): 61% said via grapevine/WOM 49% via routine follow-up 41% via community HIV team 13% formal network meetings 21% other. Information on deaths (cont) When asked how they would find out if HIV patients referred to tertiary/specialist services had died: 34% did not answer 20% described active follow up 26% described passive receipt of feedback 3% gave answers suggesting they might not always know Information was unclear for the remainder. Reporting of deaths 76% of respondents said deaths of HIV patients at their centres are routinely reported to the Health Protection Agency 2% said deaths were not routinely reported 7% had experienced no deaths 15% were unsure or did not answer. Reviews of HIV deaths Centre policies on reviewing deaths among adult patients receiving HIV care: 24% formally review all deaths 11% review in specific circumstances 20% review if clinicians have concerns 39% no clear policy 5% not sure or no answer. Death review process 22% of centres involve hospital/community MDT 28% hospital MDT 28% medical team only 8% other 14% no answer. At 48% of centres at least some reviews involve discussing the death at a meeting. Other methods include reading case notes. Death review content Issues usually considered in reviews of HIV deaths (more than one answer allowed): 82% clinical care at the centre concerned 59% clinical care elsewhere, if relevant 59% social circumstanes 55% pattern of attendance 8% other. Value of death reviews 5% of respondents rated as “very valuable, have led to significant changes in policy or practice” 27% as “valuable, have led to modest changes in policy or practice” 31% “Useful for education only” 2% “Not useful” 35% not sure or no answer. Impact and lessons learnt from death reviews Consultant-led decisions to test for HIV in unconscious patients Stopped using D4T/ddI backbone Refer complex cases to regional centre early in illness Check CD4 for new patients via pathology computer link within 2 days instead of waiting for paper results, and act if <200 Impact and lessons learnt from death reviews, continued Need for multi-disciplinary involvement at all stages of care – established social worker post for black/ethnic minority patients Influenced prescribing policy HIV team alerted each time a patient is admitted (for reasons other than HIV) Previous 3 deaths in prisoners with previously undiagnosed HIV. Agreed with physicians to refer inpatients to large centre. Impact and lessons learnt from death reviews, continued Greater awareness of causes of death Improving communication between parties and setting up a care pathway Add antifungal agents in PCP at day 7 unless much improved. Pericardial effusion - drain always when necessary and assume it's TB. Start TB treatment early in ill patients & try to prevent stroke etc Review of diagnostic procedure. Impact and lessons learnt from death reviews, continued Encourages involvement of primary care in management of non-HIV-related health problems Alerted GPs to be more vigilant about atypical, and usually late, presentation Decision to refer complex cases to regional centre early Timely discharge summaries. Better liaison between inpatient and outpatient HIV services Improved the procedures of shared care. Impact and lessons learnt from death reviews, continued Improved readiness to use empirical TB therapy Hospital consultants & other medical colleagues more aware about when to request HIV test Helped [?TB] teams to liaise and communicate with more involvement of the HIV team Planned improved communication with other parties Better liaison between surgeons and medical teams. Impact and lessons learnt from death reviews, continued Managing complex cases in the community increase awareness amongst primary care, district nursing and palliative care teams Increased awareness of lactic acidosis, its risk factors and need to collect blood in right bottle Clinical and management lessons. Impact and lessons learnt from participating in this audit Centre X: “I have found this a very educational exercise on many levels. “… the sicker patients… have been in [referral centre] at the time of their death… “… patients who are on the wards at [our own centre] are under the care of the medics and although we think we know about most of them this is not always the case. [regarding the cases submitted] “…This has immediately revealed huge data gaps and a lack of communication between the various centres”. Impact and lessons learnt from participating in this audit, cont. Centre Y: “… considerable disorder… many parts of the clinical record were effectively irretrievable… “… disregard for the importance of medical records of the relatively recently deceased… “… a matter I will take up with our Medical Director”. Case note review 89 centres submitted case note review data for 397 deaths among adults with HIV: 10 died outside the audit period of October 2004-September 2005 and were excluded from analysis. The date of death was missing for a further 8. These were included in the analysis. Thus 387 deaths were analysed. Patient demographics Not stated 2% Not stated 4% Other 5% Black-Caribbean 2% Female 24% Black-African 33% Male 74% White 57% Age and place of death Not stated 1% Not stated 4% <30 7% Outside UK 2% >50 27% UK community 22% 30-50 65% UK hospital 72% Injection of non-prescribed drugs 309 (80%) of patients had no history of injecting drug use 33 (9%) had such a history but stopped prior to their final illness 18 (5%) continued injecting drug use until onset of final illness. 27 (7%) not known. CD4 and VL in last six months of life 0-50 51-100 101-200 201-350 >350 Not available 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% CD4 in cells/ml >100,000 10,0011001-10,000 401-1000 51-400 0-50 Not available 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% VL in copies/ml Immediate cause of death Bacterial sepsis PCP TB Other OI Lymphoma KS Dementia Other malignancy Multiorgan end-stage HIV CVD Renal Other disease probably related to HIV Chronic liver disease due to co-infection/alcohol Suicide Accident/injury Overdose Other, not related to HIV Not known 0% Top bars: reclassified during audit Bottom bars: as initially reported 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% 14% Percentage of patients Scenario leading to death Death not directly related to HIV Diagnosed too late for effective treatment Under care but had untreatable complication Treatment ineffective due to poor adherence Chose not to receive treatment Known HIV, not under regular care, re-presented too late MDR HIV, run out of options Successfully treated but suffered catastrophic event Unable to take treatment - toxicity/intolerance Died in community without seeking care Treatment delayed/not provided because ineligible for NHS None of above NK/not stated 0% Top bars: reclassified during audit Bottom bars: as initially reported 10% 20% 30% Percentage of deaths 40% Deaths not directly related to HIV 123 (32%) of deaths were considered not directly HIVrelated. These comprised: 30 (7.8% of all deaths) malignancies 22 (5.7%) liver disease 17 (4.4%) CVD 7 (1.8%) suicide 7 (1.8%) sepsis 6 (1.6%) accident/injury, including one homicide 4 (1.0%) overdose 1 (0.3%) renal disease 29 (7.5%) other or not stated. Malignancy deaths were as follows: 29 lymphoma* 6 liver (of which 2 reported as liver disease rather than malignancy) 6 lung or bronchus 3 anal* 2 adenocarcinoma 2 kidney * Considered directly related to HIV ** One considered directly related to HIV. 2 oesophagus 2 penis 2 prostate 1 each bladder, bowel, breast, cervix*, Merkel cell, multiple myeloma, pancreas 5 not known or not stated** Cardiovascular disease CVD was the immediate cause of death for 25 (6.5%) patients. This was not all IHD: 2 HIV-related pulmonary hypertension 1 sub-arachnoid haemorrhage in alcoholic patient with cardiomyopathy 3 other cardiomyopathy 1 viral myocarditis. 17 of the 25 CVD deaths were classified by the reporting centre as not related to HIV. Impact of late diagnosis of HIV 88 (23%) deaths were reported as due to HIV diagnosis too late for effective treatment 5 further deaths occurring within 3 months of diagnosis were reclassified as due to late diagnosis, giving a total of 93 (24% of all deaths, 35% of HIVrelated deaths) This is a minimum as some deaths attributed to untreatable complications of HIV involved conditions which early treatment could have prevented. Also, there may be under-ascertainment of deaths occurring without involvement of HIV specialist services. Late-diagnosed patient characteristics Among patients whose deaths attributed to late diagnosis of HIV: 10.8% were aged under 30 compared with 5.8% dying in other scenarios 31.2% were white compared with 65.0%. Causes of death related to late diagnosis Causes of deaths attributed directly to late diagnosis of HIV were: 28 PCP 16 OI 9 TB 8 lymphoma 8 sepsis 7 multi-organ HIV 3 KS 3 CVD 2 renal 1 malignancy 6 other or multiple HIV related 2 not known Clinician delay in diagnosis In 16 cases, the narrative suggested possible clinician delay in diagnosing HIV after the patient had presented with symptomatic illness: 8 (50%) of these patients were over 50 at death (7 of whom were white), compared with 96 (26%) of other deaths Co-morbidity may have confused the picture in at least two cases (established IHD, previous lung cancer). HIV testing in the ill patient Two cases of clinician delay in diagnosis raise questions about HIV test procedures for ill inpatients: Case 1: Admitted with weight loss and diarrhoea. Diagnosed HIV+ by GUM health advisor while on general medical ward, after which care transferred to ID team. It is unclear why the medical team did not test for HIV without requiring involvement of GUM health advisor. HIV testing in the ill patient, cont Case 2: Presented with PUO 3/52 before GU involved. Xray showed features of PCP months before admission. Case was formally reviewed at grand round which concluded that “sexual history taking should be mandatory” as part of PUO investigation. It is unclear why sexual history taking was identified as the priority, rather than HIV testing. Starting HAART Six deaths resulted from new or worsening disease soon after starting HAART, including three due to cryptococcal meningitis. These deaths may have included cases of IRIS. Adverse reactions to therapy Five deaths were reported as definite or probable adverse reactions to HIV-related therapy: 3 lactic acidosis 1 fulminant liver failure attributed to isoniazid 1 pneumonia possibly associated with nonHodgkins lymphoma chemotherapy-related bone marrow suppression. One death was reported as an adverse reaction to non-HIV therapy – osteoporosis due to steroids for polymyositis, leading to tibia fracture and then bronchopneumonia/sepsis. Adverse reactions, cont. Reported “possible” adverse reactions were more vague, but included: Patients who deteriorated after starting HAART as reported above 3 CVD/MI - one reported as heavy smoker, TC 5.4 TG 3.5, no family history Cardiac arrest possibly secondary to hyperkalaemia in lymphoma patient Liver failure secondary to NASH, “multifactorial aetiology including NRTIs and alcohol” Possible bowel perforation related to KS or steroid therapy for PCP. Catastrophic events Seven deaths were classified as catastrophic events in patients on treatment: 3 lactic acidosis + 1fulminant liver failure (from previous adverse events slide) 1 MI - strong family history not recognised because adopted 1 right temporal lobe infarction secondary to VZV vasculitis 1 pulmonary embolus. Patient factors Patient choice not to receive treatment accounted for 18 deaths. At least 3 had previously taken ART. 26 deaths were directly attributed to treatment being ineffective through poor adherence. A history of poor adherence was noted in five other cases – 3 where death was attributed to running out of treatment options for MDR HIV and 2 attributed to untreatable complications. Poor attendance was noted in 2 further untreatable complications cases. Deaths due to poor adherence Causes of deaths attributed directly to treatment being ineffective because of poor adherence were: 12 sepsis 2 PCP 2 multi-organ HIV 1 KS 1 systemic leishmaniasis 1 PML 1 dementia 1 pulmonary hypertension 1 disseminated MAI 1 presumptive MTB 1 cerebral toxoplasmosis + nosocomial bronchopneumonia 1 died with severe muscle wasting / diarrhoea 1 “advanced HIV disease” Patient factors, cont. 13 patients with a previous positive HIV test had not been under regular care and re-presented too late for effective treatment (including one who had not returned to receive the test result). 4 patients who were diagnosed late with HIV were reported to have previously refused testing. UK residency and NHS entitlement 12 patients were known to have arrived in the UK within six months of death: 9 died as a result of late diagnosis of HIV One death was not directly related to HIV (hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatitis B/C coinfection). No deaths were reported as due to treatment being delayed or denied because of ineligibility for NHS care. Other possibly remediable factors 26 cases suggested other possibly remediable factors: Various communication and shared care issues Delay in critical care admission/incomplete medical review on transfer Need for pre-HAART CRAG testing for Africans with low CD4 Awareness of lactic acidosis and collecting blood in the right bottle Earlier consideration of CMV treatment Other possibly remediable factors, cont. Need for early oncology input in KS More intensive therapy for Burkitt’s lymphoma Greater support for patient in denial re HIV status Missed histology report Importance of encouraging people to start treatment when indicated More aggressive management of osteoporosis. Post mortem and review Post mortems were known to have been done in 57 (15%) cases. Of these, 41 were coronial, 11 consented and information was missing for 5. Refusal of consent was cited as a reason for not performing a PM in 22 cases. Lack of access to pathology was cited in 13 cases from 7 centres. Post mortem and review, cont. 104 (27%) deaths had been reviewed at the reporting centre, and review was planned for 34 (9%). 211 (55%) deaths had not been reviewed. Information was lacking for 38 (10%). Certification of deaths due to HIV According to the centre questionnaire: 60% of respondents always write HIV on the certificate and/or tick the box to indicate more information available 1% sometimes neither write HIV nor tick the box 35% have not certified HIV deaths 5% were not sure or did not answer. Death certification, cont. However, in the case note review, HIV was not written on the certificate and the box was not ticked in 39 (10%) cases. Only 12 of these 39 deaths were reported as not directly related to HIV (a further 4 were re-classified as such during the audit) Information about the certificate was lacking in 195 (50%) cases. Conclusions Late diagnosis and causes not directly related to HIV account for the majority of deaths in adults with HIV. There is some evidence of clinician delay in diagnosing HIV. Deaths due to adverse reactions to HIV therapy are reassuringly rare. Conclusions, cont. Specific causes of death are predominantly: “Classical AIDS” including PCP, sepsis, lymphoma and TB Malignancies Liver disease due to hepatitis B/C coinfection and/or alcohol Cardiovascular disease. Conclusions, cont. This study has identified some specific issues, including: Mechanisms for informing centres when patients have died in the community or at tertiary referral centres Importance of good communication and prompt, effective referral pathways Value of death reviews Awareness of lactic acidosis Need for improvement in death certification. Conclusions, cont. For some centres, data gathering for this study has been an instructive exercise in itself, and has identified issues of communication and recordkeeping. Recommendations BHIVA requests its members to discuss these findings at local grand rounds, to communicate the impact of late HIV diagnosis to non-HIV clinicians and jointly consider how to facilitate rapid diagnosis and transfer of patients to specialised HIV care. BHIVA asks EAGA and the Department of Health to consider how to promote more routine HIV testing in generic services as well as specialist HIV/GU/sexual health settings.