here it is

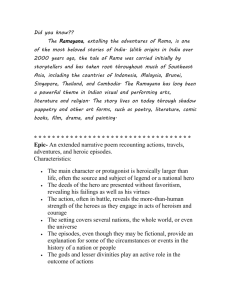

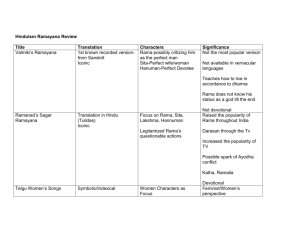

advertisement

Rewritings of the Women of the Ramayana and of the Matter of Britain A calendar traditionally ascribed to Nennius, a scribe of the ninth century (though the actual composer is unknown), told of the "Battle of Badon in which Arthur...and the Britons were victors" and of "The strife of Camlann in which Arthur and Mordred perished". Guinevere is probably invented, but her story has been told and retold; she is part of the essential mythos. The Matter of Britain is a name given collectively to the body of literature and legendary material associated with Great Britan and its legendary kings, particularly King Arthur; it was one of the three great literary cycles recalled repeatedly in medieval literature. Guinevere’s portrayal shifts through the ages. "In some stories, Guenevere is unusually interested in displaying the heads of enemies Arthur killed in battle. This would be uncharacteristic of the traditionally demure [twelfth century], gentle Guenevere. But it would be natural for a Celtic warrior-queen" (Andronik, Quest for a King). Different versions of her story reflect the time in which they were written, as can be seen in the twelfth-century Chretien de Troyes' Arthurian Romances, Sir Thomas Malory's fifteenth-century Le Morte d' Arthur, Lord Alfred Tennyson's eighteenth-century Idylls of the King, T.H.White's early twentieth-century The Once and Future King, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Mists of Avalon, and Jane Yolen's twentieth-century short story "Meditation in a Whitethorn Tree". Raymond H. Thompson, an Arthurian scholar, notes that "[t]o the composers of French romance, who discovered Arthur in the twelfth century and spread his fame throughout Europe, he was no Dark Age chieftain but a dignified medieval monarch commanding the most renowned chivalry in the world" ("Afterword: Camelot Considered", Invitation to Camelot, 253) "[Lancelot] comes to...the queen, to whom he bows in adoration, for no holy relic inspires him with such faith" (247). They are described as being at the mercy of their love, for "[t]he warmth of her welcome is motivated by love; and...his love for her was a hundred thousand times as great, for love in all other hearts was nonexistent compared with that in his own" (247). Eventually, Lancelot must leave and when "he did so he was a true martyr: so distressed was he at the parting that when it came he endured terrible martyrdom" (247). They have no power to resist their overwhelming love, for "his heart is ceaselessly drawn back to where the queen remains; and he has no power to take it away...the body goes, but the heart stays behind" (2478). When they are reunited after being separated, “[n]ever before had she been so jubilant as she is now on his return…she is so close to him that her body virtually came within an ace of following her heart. - Where, then, is her heart? – It was kissing and making much of Lancelot. - Why, then was her body hiding?...it is possible that the king or some of the others there...would have quickly become aware of the whole situation....And had Reason not rid her of this foolish thought...they would have seen just what her feelings were, and that would have been the height of folly (276-7).” It seems that Guinevere's love is not seen as being as strong as Lancelot's; it is more "foolish" but she is still overpowered by it. The twelfth-century seems to see their love as being unfortunate but not evil. Guinevere and Lancelot are still viewed as passionate lovers; "ever his thoughts were privily on the queen, and so they loved together more hotter than they did toforehand" (Malory, vol 2, 271), consumed by their love, although the concept of sin becomes more prevalent here than in the twelfth-century work. Indeed, Malory holds up Guinevere as an example for all lovers, saying they should "call unto [their] remembrance the month of May, like as did Queen Guenever, for whom I make here a little mention, that while she lived she was a true lover, and therefore she had a good end" (Malory, vol 2, 315). Malory does not state whether they had sex or not, but it is implied that they have, ...and so he passed till he came to the queen's chamber, and then Sir Launcelot was lightly put into the chamber. And then...the queen and Launcelot were together. And whether they were abed or at other manner of disports, me list not hereof make no mention, for love that time was not as it is nowadays (Malory, vol 2, 343). Malory does not seem to be condemning her for the crime of adultery, but rather for allowing suspicions to grow which bring about the ruin of herself, her love and her husband. Guenevere says of Lancelot, "Through this man and me hath all this war been wrought, and the death of the most noblest knights of the world; for through our love that we have loved together is my most noble lord slain" (Malory, vol 2, 394). She has sinned, and must do penance, "I trust through God's grace that after my death to have a sight of the blessed face of Christ,...for as sinful as ever I was are saints in heaven" (Malory, vol 2, 394), but she is not portrayed as evil, merely tragically wrong. The ruin of the Round Table in Malory comes at the hands of Mordred, and is a direct result of Arthur’s choice to kill the children, in the attempt to forestall a prophecy: In Malory's work Arthur tries to avoid his fate as prophesied by Merlin: "'...ye have lain by your sister, and on her ye have gotten a child who shall destroy you and all the knights of your realm'" (30). Arthur tries to avert this fate by ordering the killing of all young children: “Then King Arthur sent for all the children born on May-day begotten by lords and born of ladies, for Merlyn had told the king that he who would destroy him and all the land would be born on May-day: wherefore he sent for them all upon pain of death. So many lords' sons and many knights' sons were found, and all were sent unto the king; Mordred as sent by King Lot's wife. All were put to sea in a ship, and some were four weeks old and some less. So by fortune the ship drove into a castle and was all shattered and for the most part destroyed, save that Mordred was cast up and a good man found him and fostered him till he was fourteen years old.” (38). The queen is portrayed as a sinful, shameful woman whose name "[w]ould be for evermore a name of scorn" (Tennyson, 226). Their love is not admired as all-powerful and overwhelming as it was in earlier centuries when the courtly love tradition was in force, rather they are "traitors" to the kingdom. Such words as shame, scandal, disloyalty, sin, and evil are common throughout the chapter on Guinevere. Not only do others condemn them, but the lovers themselves speak of the actions as shameful, "O Lancelot, get thee hence to thine own land, For if thou tarry we shall meet again, And if we meet again some evil chance Will make the smouldering scandal break and blaze Before the people and our lord the King" (Tennyson, 226). Guinevere cries out when they are trapped by Mordred, "'The end is come, /And I am shamed for ever", and, when Lancelot attempts to take some of the blame onto himself, she rebukes him, saying, "Mine is the shame, for I was wife, and thou /Unwedded" (Tennyson, 226). After Guinevere takes refuge in a nunnery a novice tells her how throughout the land the stories tell of "the good King and his wicked Queen" (Tennyson, 229). The girl says that the tragic story "...all is woman's grief, /That she is woman, whose disloyal life /Hath wrought confusion in the Table Round /Which good King Arthur founded, years ago, /With signs and miracles and wonders, there /At Camelot, ere the coming of the Queen" (Tennyson, 230). Once, Guinevere was the Victorian ‘angel in the house,’ the very ideal of chivalry and goodness, an emblem for the just kingdom that Arthur is trying to create. But once she has adulterous sex, she becomes the whore, the cause of corruption in the world, traced back to Eve’s stealing the forbidden fruit from God; “glad were spirits and men /Before the coming of the sinful Queen" (Tennyson, 231). Tennyson requires that Guinevere be punished for this sin, when confronted by Arthur, Guinevere must abase herself before him, "...prone from off her seat she fell, /And grovell'd with her face against the floor. /There with her milk-white arms and shadowy hair /She made her face a darkness from the King" (Tennyson, 234), a striking contrast to an earlier Guinevere who proudly accepted her fate. Where in other versions he would take her back if he could, here he says “Yet must I leave thee, woman, to thy shame. I hold that man the worst of public foes Who either for his own or children's sake, To save his blood from scandal, lets the wife Whom he knows false abide and rule the house... She like a new disease, unknown to men, Creeps no precaution used, among the crowd, Makes wicked lightnings of her eyes, and saps The fealty of our friends, and stirs the pulse With devil's leaps, and poisons half the young” (Tennyson 236-7). [o]ne explanation of Guenever,...is that she was what they used to call a "real" person. She was not the kind who can be fitted away safely under some label or other, as "loyal” or "disloyal" or "self-sacrificing" or "jealous". Sometimes she was loyal and sometimes she was disloyal. She behaved like herself (White, 497). [i]t is difficult to explain about Guenever, unless it is possible to love two people at the same time. Probably it is not possible to love two people in the same way, but there are different kinds of love...In some way such as this Guenever did come to love the Frenchman [Lancelot] without losing her affection for Arthur (White, 378). "[Arthur] knew perfectly well that they were sleeping together - knew too, unconsciously, that if he were to ask his wife, she would admit it. Her three great virtues were courage, generosity and honesty" (White, 407). Other twentieth century writers have also resisted the sinful depiction of Guinevere – several, such as Yolen (“Meditation in a Whitethorn Tree”) and most notably Bradley (Mists of Avalon), have recentered the tale on Guinevere and the other women of the court, telling it from their viewpoints, and resisting the narrative that would make Guinevere an icon of virtue or doom. Not precisely a retelling, Kay utilizes a portal fantasy in this trilogy in order to give the Arthurian threesome a happy ending. This is my favorite version. The Ramayana tells about life in India around 1000 BCE and offers models in dharma. The hero, Rama, lived his whole life by the rules of dharma; in fact, that was why Indian consider him heroic. When Rama was a young boy, he was the perfect son. Later he was an ideal husband to his faithful wife, Sita, and a responsible ruler of Aydohya. "Be as Rama," young Indians have been taught for 2,000 years; "Be as Sita.” “…the Ramayana is not simply a story of the victory of good over evil, but…it is also a metaphor for the battle in the soul.” (Singh) The original Ramayana was a 24,000 couplet-long epic poem, written somewhere between 500-100 B.C., and attributed to the Sanskrit poet Valmiki (within the poem). Oral versions of Rama's story circulated for centuries, and the epic was probably first written down sometime around the start of the Common Era. It has since been told, retold, translated and transcreated throughout South and Southeast Asia, and the Ramayana continues to be performed in dance, drama, puppet shows, songs and movies all across Asia. 6:45 – 11:26: Intro to Rama’s story This film was inspired in part by Paley’s own life; her husband took a job in India, and then eventually abandoned her. The film's distribution sparked an intense debate regarding the portrayal of Hindu culture in Western media and was even met with outrage by some Hindus and, according to the film-maker, a number of left-wing academics also. In april 2009, a group called the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti started a petition calling for a complete ban on the movie and initiation of legal action against all those who have been involved in its production and marketing, believing its portrayal of the Ramayana to be offensive, with some members even going so far as to call it “a derogatory act against the entire Hindu community.” “They have been in the forest for days, weeks, years. They have been in exile so long that the princess has forgotten what it is to see a familiar face, a face other than that of her husband or his brother. Sita has only monkeys for company, who screech and gibber in the day, in the night, endless in their complaints. With wide faces and brazen eyes, they follow her as she moves barefoot through her days, her crimson wedding sari (all she owns in this exile) like a slender flame in the forest. The monkeys do not worry her; she is a princess, after all, and her husband is a prince. She has nothing to fear from monkeys. But his brother watches too, with eyes wide and shameless. Rama is oblivious, will think no evil of his brother. But Sita knows; she feels it. His heated gaze strips the silk from her skin, leaving her naked and trembling.” – Mohanraj, “The Princess in the Forest” Prince Rama was the eldest of four sons and was to become king when his father retired from ruling. His stepmother, however, wanted to see her son Bharata, Rama's younger brother, become king. Remembering that the king had once promised to grant her any two wishes she desired, she demanded that Rama be banished and Bharata be crowned. The king had to keep his word to his wife and ordered Rama's banishment. Rama accepted the decree unquestioningly. "I gladly obey father's command," he said to his stepmother. "Why, I would go even if you ordered it.” When Sita, Rama's wife, heard Rama was to be banished, she begged to accompany him to his forest retreat. "As shadow to substance, so wife to husband," she reminded Rama. "Is not the wife's dharma to be at her husband's side? Let me walk ahead of you so that I may smooth the path for your feet," she pleaded. Rama agreed, and Rama, Sita and his brother Lakshmana all went to the forest. Later in the story, Ravana, the evil King of Lanka, (what is probably present-day Sri Lanka) abducted Sita. Rama mustered the aid of a money army, built a causeway across to Lanka, released Sita and brought her safely back to Aydohya. In order to set a good example, however, Rama demanded that Sita prove her purity before he could take her back as his wife. Whereas Guinevere holds the images of virtue and sin within one figure, in the Ramayana, these roles are divided. Sita is the noble queen, pure and virtuous. Suprakshna is the demon who attempts to seduce Rama, and is punished by having him chop off a variety of body parts. Surpanakha (Sanskrit for "sharp, long nails"; is one of the most important characters in the Ramayana. Indeed, Valmiki comes close to claiming that if there had been no Surpanakha, then there would have been no Ramayana and no war with Ravana. Surpanakha was the arrow that set in motion the events leading directly to the destruction of Ravana; hence she often gets the blame as being the evil genius behind, and the sole cause of, the Ramayana war. Surpanakha met the exiled Rama and was smitten; Rama spurns her advances, telling her he is devoted to his wife, Sita, and would never take another wife. Rama suggests she approach his brother Lakshmana; Lakshmana derides Surpanakha and tells her that she was not what he desired in a wife. The humiliated and jealous Surpanakha attacked Sita but was thwarted by Lakshmana, who cut off her nose and breasts and sent her back to Lanka. Valmiki's description of Surpanakha: An ugly woman (gora mukhi), pot bellied and crosseyed. Thinning, brown hair. A grating voice that is harsh on the ears. Oversized breasts—which can be translated to mean a heart full of wickedness. Edited by Anil Menon and Vandana Singh “Hold on to a story long enough and it begins to make a people.” – Menon “The idea that there is ‘the’ Ramayana is one of those South-Asian facts: true wherever it is not false. As A.K. Ramanujan’s wonderful must-read essay Three Hundred Ramayanas shows, there are many Ramayanas. The tradition is to depart from the tradition…” “Even more radical is the Chandravati Ramayana. Composed by a sixteenth-century female poet and bhaktin, it is mostly about Sita; a feminist Ramayana.” “The South Asians were also fascinated with language. As the linguist Frits Staal remarked, what geometry was to the Greeks, language was to the ancient South Asians. This fascination, combined with their speculative imagination, led to stories that pushed the boundaries of what was possible with language: selfreflective stories, meta-fiction, fractal stories, frame stories stacked eight or nine levels deep, stories in which reality and fiction merged seamlessly, stories that encoded other stories, stories which questioned embodiement, gender and identity…” - Menon “It was my grandfather…who first gave me a hint that there were multiple Ramayanas. He loved many aspects of the ancient texts…[y]et he did not hesitate to criticize when he had good reason to do so. (One of the great freedoms of Hinduism is surely the lack of a Big-Brother-style religious police to prevent you from having your say)….Once he told me that there were many versions of the Ramayana, and that some versions contained interpolations that were clearly anchronisic, containing references that belonged to times later than that of the original story….Now I think of the Ramayana as a kind of palimpsest, a tapestry in multiple layers…” -- Singh At first, Sapna appears to have agency; she is only playing Surpanakha’s role, and events are at least somewhat under her control. “I smile at him and he grabs me by the wrist and painfully turns me around, holding my arm against my chest and groping at my breasts. I elbow him off of me but he grabs a hold of my waist and grinds into my ass instead. I elbow him again but it makes him grab me even tighter and I surrender to his breath in my ear. Luckily the timer goes off and I turn around violently. ‘Ravana, don’t you recognize me?’ I scream ipping off my blonde wig and skullcap and letting my thick black hair tumble out. ‘It is I, Surpanakha, your demonness sister!’” (26) “I humble myself, begging Ravana’s forgiveness but raise myself enough that he can swing the hologram sword at me, pretending to chop off my breasts, nose and ears, blood gushing up from special pipes in my costume. When he looks down, all he sees is my hair whipping about in rivulets of red. While I am screaming and thrashing, the monitors start flashing: ‘Thank You for Playing at Exile! Please exit to Account Kiosk!’” (26) In the end, however, Sapna is enslaved by economic issues; to save her mother’s life, she must take on more dangerous role-play work on the space colonies; Supranakha cannot escape her role, although the power dynamics have shifted. Guinevere, Sita, and Supranakha all function as both reflections of their societies’ attitudes towards women, and as potentially transformative figures, through which authors and literary consumers attempt to re-envision their possible roles. Even though Sita is overdetermined as the ‘good wife’ and Supranakha as the ‘demonness,’ both characters are so rich and complex, their mythos so varied and multifarious, as to allow for an immense, almost endless, set of possibilities.