Trends_Developments_..

Trends and

Developments in

IT Procurement

IT.CAN Information Technology Law Spring Forum

May 4, 2015

Paul Emanuelli

General Counsel and Managing Director

Procurement Law Office paul.emanuelli@procurementoffice.ca

416-700-8528 www.procurementoffice.ca

Copyright Notice

The following excerpts from Government

Procurement (copyright LexisNexis Butterworths

2005, 2008 and 2012), The Laws of Precision

Drafting (copyright Northern Standard Publishing

2009), Accelerating the Tendering Cycle (copyright

Northern Standard Publishing 2012), The

Procurement Office Blog (copyright 2011-2015) and the National Tendering Law Update (copyright

Paul Emanuelli 2006-2015) are reproduced with permission. The further reproduction of these materials without the express written permission of the author is prohibited.

© Paul Emanuelli, 2015

For further information please contact: paul.emanuelli@procurementoffice.ca

.

About the Author

Paul Emanuelli is the General Counsel and

Managing Director of the Procurement Law Office.

He has been ranked by Who’s Who Legal as one of the ten leading public procurement lawyers in the world and his firm was selected by Global Law

Experts and Corporate INTL as Canada’s top public procurement law firm. Paul’s portfolio focuses on major procurement projects, developing innovative procurement formats, negotiating commercial transactions and advising institutions on the strategic legal aspects of their purchasing operations. Paul also has an extensive track record of public speaking, publishing and training. He is the author of Government Procurement, The Laws

of Precision Drafting, Accelerating the Tendering

Cycle and the National Tendering Law Update.

Paul hosts the Procurement Law Update webinar series and has trained and presented to thousands of procurement professionals from hundreds of institutions across Canada and internationally.

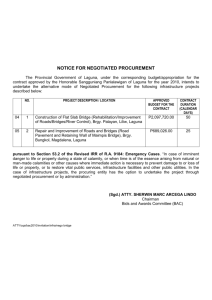

Deploying Defensible NRFPs

Industry Overview and Implementation Guardrails

This presentation will provide a survey of the jurisdictions and sectors that are adopting flexible negotiated RFP formats. It will also offer practical guiding principles for the implementation of NRFPs, with an emphasis on proper project design planning and on establishing the following

“guardrails” for ensuring the transparency and defensibility of evaluation and award processes: (1) a clear scoping of the contract opportunity; (2) transparent evaluation criteria; (3) transparent evaluation and award process paths.

4

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

With an increasing number of Canadian purchasing institutions adopting international best practices and implementing flexible, low-risk negotiated RFP models for everything from construction to information technology contracts, how long will it be before competitive bidding evolves to render the high-risk and inflexible “Contract A” operating system completely extinct?

This article by Paul Emanuelli was previously published in the Summer 2013 inaugural edition of Negotiated RFP Newsletter.

5

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

It has been over thirty years since the Supreme Court of

Canada’s R. v. Ron Engineering decision imposed fixed-bid

“Contract A” legalities onto the Canadian tendering process and almost fifteen years since the Supreme Court’s M.J.B.

v. Defence Construction decision counter-balanced Ron

Engineering by confirming that purchasing institutions remain free to use traditional contract law to negotiate flexible low-risk competitive bidding. After years of competing operating systems, we have reached the tipping point: M.J.B.’s open contracting logic has prevailed over the rigidity of Ron Engineering. Contract A is in an irreversible decline. Negotiated RFPs are the emerging standard.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

6

Contract A: Always a Bad Fit

Why was Contract A ever used in the first place? Just as

Ron Engineering’s fixed-bid Contract A precedent was taking effect within the construction sector, senior governments across Canada were establishing trade treaties that required open, competitive bidding for most significant government purchases. Governments needed to quickly establish an operating system to facilitate these new requirements, so they repurposed the construction industry’s fix-bid tendering format and imposed its idiosyncratic rules on everyone else.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

7

Preconditions for Fixed-Bid Tendering

Lost in that equation was the fact that there were a number of pre-existing industry conditions that led to fixed-bid tendering in the construction industry, including an army of independent architects and engineers ready to prepare detailed specifications for the owners, an established industry group that created standard-form contract boilerplate to incorporate into tendering documents, and a prime-subcontractor supply chain that was ready to bid on pre-fabricated tender calls with bid bonds provided by the bonding industry.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

8

Systemic Defects

This combination of critical pre-conditions does not exist in other industries, yet under Contract A all sectors were called on to bid on government contracts under the same operating system used for construction tendering. Outside of the construction sector, this led to significant problems in designing and awarding contracts suited to the specific industry and project. By the 1990s, the systemic defects were largely apparent to anyone following the case law or in tune with conditions at the front lines of the procurement cycle.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

9

The Supreme Court Reboots Bidding

By confirming a clear passage out of Ron Engineering’s

Contract A minefield, the Supreme Court’s M.J.B. decision served as the catalyst for rebooting the procurement cycle.

Giving purchasing institutions the right to choose another operating system for competitive bidding that allowed them to cut through piles of red tape, avoid countless legal entanglements and negotiate refinements to align their tendering formats with a broader range of industries was a better fit than imposing a one-size-fits-all solution onto every tendering process.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

10

A Superior Operating System

More and more purchasing organizations soon began realizing that client satisfaction, supplier engagement and overall compliance with open tendering obligations could be increased by adopting a more flexible approach to tendering. The bottom line was that traditional contract law was proving to be a superior operating system, working better in more situations than the mass-produced Contract

A steamroller.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

11

Construction Moves Beyond Contract A

In this tale of two operating systems, the post-M.J.B. years have seen a steady erosion of the once seemingly unassailable Contract A operating system. In fact, even within the construction sector, we see an accelerating migration towards flexible formats. This is particularly true domestically and internationally in the use of negotiated RFPs for complex and high-risk P3 projects. The endorsement of these formats in the United Nations Commercial Contracting Committee’s

Model Procurement Law and Model Legislative Provisions on

Privately Financed Infrastructure Projects further underscores the mainstream and widespread adoption of flexible formats

within the construction industry.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

12

The Tipping Point of Innovation

Outside of the construction sector, change has occurred at an even faster pace. The spark of innovation has been lit on multiple fronts. From the Atlantic to the Pacific, the

Arctic to the Equator, the standardized process-driven approach to tendering has lost ground to a more principled, nuanced and substantive approach. The tipping point has arrived within Canada and across many other

Commonwealth jurisdictions.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

13

The Negotiated RFP Works Better

Rectification Processes

The negotiated RFP has set the new standard by simply working better at meeting the overall needs of the tendering cycle. For example:

• When bids contain technical irregularities, it’s no longer necessary to disqualify bidders. Transparent rectification processes can now be used to maximize competition by allowing all proponents to cure irregularities in their bids, thus ensuring full competition while avoiding tender compliance lawsuits.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

14

The Negotiated RFP Works Better

Avoiding Budget Roadblocks and Bid Shopping Battles

• When bids come in over budget, it’s no longer necessary to cancel and retender and expose the institution to project delays and potential bid shopping lawsuits. While

Negotiated RFPs permit the safe termination of a bidding process, they also help organizations avoid retendering by enabling transparent post-bid price adjustments so contract awards can be made on time and on budget.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

15

The Negotiated RFP Works Better

Fine-Tuning Contract Terms

• When a selected proponent wants to discuss contract terms, it’s no longer necessary to impose pro forma boilerplate agreements with “take it or leave it” ultimatums.

Where required, flexible formats permit the post-bid dialogue necessary to tailor contract terms to better reflect the interests of both parties.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

16

The Negotiated RFP Works Better

Enabling Creative Solutions

• When suppliers propose a creative solution that can save time and money, it’s no longer necessary to leave value on the table and reject new approaches. Negotiated RFPs allow you to obtain improved performance standards and improved pricing through structured, transparent and defensible negotiation processes.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

17

The Process Serves the Purpose

With Contract A tendering, the need to avoid getting sued often trumps the need to put a contract in place and have the requirements delivered on time. Rather than paving over the strategic objectives of a transaction with procedural orthodoxies, the use of flexible formats has re-established the paramount importance of achieving the desired outcome. With flexible Negotiated RFP formats, process no longer needs to be an end in itself. Timely results matter.

The final contract is once again paramount.

The Rise of Negotiated RFPs

18

Moving Forward with Innovation

After years of innovation and success, the debate over

whether institutions should use flexible tendering formats is over. The verdict is in. The industry is voting with its feet in its race to adopt flexible tendering formats.

19

Moving Forward with Innovation

BC adopts JSP BAFO

NRPs in early 2000s.

Manitoba runs RFP to design and implement

NRFPs in 2014.

NRFP test pilot by Ontario government in 2006, formal recognition in subsequent updates of MBC and BPS

Directives.

2014 New Brunswick regulations enable formal

NRFP deployment.

Widespread

NRFP adoption in Alberta municipal sector since 2011.

Increasing NRFP adoption in

Manitoba agency and broader public sector since 2012.

Widespread NRFP adoption in

Ontario agency sector and broader public sector since 2009.

21

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

In its May 2007 determination in Re Zenix Engineering Ltd., the Canadian International Trade Tribunal found the government liable for unilaterally terminating contract negotiations and bypassing the top ranked proponent. While this determination implicitly recognized the use of negotiated

RFPs in the treaty-regulated federal procurement context, it also illustrated the importance of offering top ranked proponents a final opportunity to meet the government’s bottom line position before terminating talks and proceeding to the next proponent.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

21

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

The Tribunal considered the obligations regarding negotiations that were created between the government and top ranked proponent in the particular process:

According to paragraph 3.3 of RFAP, the negotiations were to include

“… an agreement on a maximum amount for services authorized by

DCC … .” The Tribunal is of the view that DCC never clearly communicated to Zenix what constituted the maximum budgeted amount authorized by DND. The Tribunal is of the view that, if the negotiation were to lead to an agreement on a maximum amount for services authorized, it was reasonable to expect that either DCC or DND would have had to identify, during the course of the negotiations, the monetary limit of DND’s budget authority.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

22

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

It also seems logical in that context that, because there were no items of discord between parties other than price, the appropriate time for communicating the nature of any budget limitations would have been when the negotiations had reached an impasse on price. In the case at hand, DND never asked Zenix to meet a price, nor were any budget limitations ever communicated to Zenix.

The meaning of the term “negotiation” is not defined in the RFAP. The

Tribunal considered the dictionary definition of the verb “to negotiate” found in the Canadian Oxford Dictionary [footnote omitted] in which it is defined as “… to confer with others in order to reach a compromise or agreement … .”

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

23

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

The Tribunal is of the view that negotiations involve a dynamic whereby parties exchange offers and counteroffers until a point where they reach either an agreement in respect of the object of the negotiations or a point where they conclude that have not reached an agreement. The concept of negotiation implies a communication between parties as to the items that are essential to reaching a compromise or an agreement.

Negotiations are conducted within the limits that the parties set between themselves.

In the case at hand, those limits, to the extent that they existed, were found in paragraph 3.3 of the RFAP. The only limit imposed on the negotiations in paragraph 3.3 was in respect of the moment where it could be determined that the negotiations had failed.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

24

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

According to the terms of that paragraph, it would only have been at that moment that DCC would have been authorized to enter into negotiations with the next ranked proponent.

There is nothing in the language of paragraph 3.3 of the RFAP that could directly or indirectly be construed as indicating that the negotiations would be conducted in a manner that is different from what can generally be understood to take place in the context of a commercial negotiation.

Nothing in that paragraph indicated that, contrary to what would normally be expected in the context of a negotiation, DCC could unilaterally determine when the negotiations had reach the point of failure.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

25

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

The Tribunal found that the government’s failure to make a clear final offer on price before terminating negotiations and proceeding to the second ranked bidder was a breach of the

RFP rules:

… DCC unilaterally terminated negotiations with Zenix and began negotiations with the next ranked proponent. [footnote omitted] Contrary to what would have been reasonable to expect under the terms of paragraph 3.3 of the RFAP, DCC unreasonably decided that its negotiations with Zenix had reached an impasse on the issue of price, such that it meant that the negotiations had failed. DCC reached that conclusion before ever communicating to Zenix what constituted the maximum budgeted amount authorized by DND — the very object of the negotiations.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

26

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

… The Tribunal believes that it is only after communicating this information to Zenix and having sought a final response from Zenix in this regard that DCC could have reached the conclusion that the negotiations had failed. Given what it found to be a serious breach of the procurement rules, the Tribunal awarded the improperly bypassed top ranked proponent its lost profits.

In its March 2008 decision in Zenix Engineering Ltd. v.

Defence Construction (1951) Ltd., the Federal Court of

Appeal upheld a Canadian International Trade Tribunal’s finding of liability against the government for prematurely terminating contract negotiations with a top ranked proponent.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

27

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

However, while this Court of Appeal agreed with the

Tribunal’s ultimate conclusion, it disagreed with the

Tribunal’s finding that the government was required to disclose its budget during negotiations. As the Court of

Appeal concluded, neither the specific tender call rules nor the applicable trade treaties required the government to disclose its budget during its negotiations with the top ranked proponent:

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

28

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

In my view, a proper contextual interpretation of paragraph 3.3 of the

RFAP is that in order for the applicant to award the contract, there must be an agreement between the negotiating parties on the maximum amount to be paid for services. It is quite sensible and typical of commercial negotiations that there be an agreement between the parties on the maximum amount to be paid before awarding a contract. Article

506(6) of the AIT requires that evaluation of the tenders follow the criteria outlined in the tender documents. I find that neither the RFAP itself, nor

Article 506(6) of the AIT requires that the applicant disclose DND’s budget limits to Zenix. Such a reading would prevent the applicant from being able to use its competitive advantage to obtain the optimum value for DND, which is an object of the competitive tendering process.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

29

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

I would not, however, preclude such a situation from ever occurring. If a clause of the tender documents clearly required the applicant to disclose its budget limit, then under the AIT or NAFTA Articles discussed, the applicant would be required to abide by it. However, such a requirement would require clear language in the RFAP, as it is counter to the very nature of a competitive bidding and negotiated procurement process. In my view paragraph 3.3 of RFAP is clear in not requiring the applicant to disclose its budget limit while negotiating, and the CITT had no basis or justification for making such a finding.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

30

Public Sector NRFP Negotiations Subject to Due Process

Zenix Engineering Ltd. v. Defence Construction (1951) Ltd.

Canadian International Trade Tribunal & Federal Court of Appeal

The Court of Appeal therefore recognized the government’s right to withhold its budget limits when conducting contract award negotiations, thereby preserving an element of bargaining leverage for the government during this crucial phase of the procurement process.

Negotiated RFPs and Negotiation Rules

31

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

In the fall of 2014, the Canadian International Trade Tribunal issued a trilogy of interrelated determinations in CGI

Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v.

Canada Post Corporation. The complaint involved an RFP issued by Canada Post for the award of master services agreements for the provision of data centre services. CGI was an unsuccessful proponent. It launched a series of legal challenges, taking issue with the debriefing process, with the failure of Canada Post to maintain its evaluation records, and with Canada Post’s use of information collected during site visits in its evaluation process.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

32

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

In September 2014, the Tribunal released the first of the three interrelated determinations. It found that Canada

Post had failed to comply with its debriefing duties under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) by failing to adequately disclose evaluation criteria. The

Tribunal provided an overview of the relevant debriefing duties under NAFTA and reiterated the obligation to maintain the individual notes of the evaluators when using consensus scoring since the individual scoring sheets should be provided to proponents during debriefings in order to satisfy NAFTA debriefing duties.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

33

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

In coming to this conclusion, the Tribunal rejected Canada

Post’s assertion that disclosing more detailed information about its evaluation process would result in the disclosure of confidential and proprietary Canada Post information and would compromise the quality of future proposals. The

Tribunal found that Canada Post failed to provide reasonable arguments to support these assertions:

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

34

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

Thus, information regarding the individual evaluators’ assessments of

CGI’s proposal shows part of the reasons for or approach to establishing the final scores and outcome of this solicitation; as such, it is pertinent information for the purposes of Article 1015(6)(b) of NAFTA that can help provide transparency to an unsuccessful bidder seeking to understand how its tender was evaluated. Canada Post’s failure to provide this information is rendered more egregious by the fact that the Tribunal has found, in previous decisions, that, where consensus scoring is used, the debriefing must still include the communication of the considerations of each individual evaluator who contributed to the establishment of the consensus evaluation.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

35

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

The Tribunal also found that the failure to provide a proper debriefing was a serious deficiency in the integrity of the procurement process:

The deficiency found is serious due to its broader impact on the integrity and efficiency of the competitive procurement system.

Disregarding debriefing obligations risks significantly affecting the trust of bidders and the public in the integrity of the procurement system, as well as the efficiency of the system. As stated, the debriefing obligations contemplated by NAFTA are one means of ensuring the transparency of the procurement system, which underpins the objectives of the procurement regime under the CITT Act and the trade agreements.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

36

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

In particular, debriefings serve to demonstrate that the procurement has been conducted with integrity, they provide bidders with the necessary information to assert, if need be, their NAFTA rights, and they can facilitate an early resolution of disputes between the parties.

All of these are essential for the system to function efficiently.

In light of these findings, the Tribunal directed Canada

Post to align its debriefing policies and practices with its

NAFTA obligations and ordered Canada Post to provide the required debriefing information to CGI.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

37

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

In October 2014, the Tribunal released the second of its three interrelated determinations, which focused on the duty to maintain evaluation records during consensus scoring. It noted that Canada Post had acknowledged that the destruction of the individual evaluator records during consensus scoring was a breach of its trade treaty duties and that it had initiated a review of its consensus scoring policies. As with the failures relating to the debriefing process, the Tribunal found that the failure to maintain evaluation records was a serious deficiency in the procurement process:

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

38

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

The Tribunal agrees with CGI that the destruction of documents relevant to the evaluation in a procurement process is serious due to its impact on the integrity and efficiency of the competitive procurement system. The destruction of relevant documents causes bidders and the public to view the whole procurement process with suspicion; however, confidence in that system is imperative, as it increases participation in the procurement system and increases the chances of the government getting quality goods and services at minimum expense. This inquiry is a case in point that the loss of part of the evaluation record creates additional difficulties, both procedural and substantive, in the Tribunal’s inquiry into a complaint.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

39

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

Although it was not the case here for reasons explained earlier, the loss of relevant documents and information can potentially prevent the procuring entity from reasonably justifying its decisions and the Tribunal from determining what has transpired in the procurement process; as such, the loss of pertinent documents and information can result in a procurement process being found unreasonable, even if it had otherwise been carried out in compliance with all applicable standards. Needless to say, this creates unnecessary inefficiencies, additional delays and extra costs of all kinds to the government, the bidders and, ultimately, the taxpayers.

The Tribunal therefore ordered Canada Post to change its record keeping practices to comply with its trade treaty duties.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

40

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

In October 2014, the Tribunal also released the third of its three interrelated determinations. It found that Canada

Post had improperly used information obtained during site visits of proponent facilities to increase the score of one of the proponents, and that the RFP terms did not permit this type of adjustment. The Tribunal ordered Canada Post to conduct a re-evaluation with a new evaluation team once it had updated its record keeping and debriefing practices in order to comply with the two prior determinations:

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

41

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

The deficiencies identified in this process bring into question the accuracy of all bidders’ evaluations, including the bidder that was not initially granted a site visit and those bidders that did not take part in this inquiry process. The process used to change the final scores was not consistent with the consensus scoring process used for evaluating and ranking the other bidders. The final ranking of the bidders was affected by changes to the scoring of technical proposals made as a result of the site visits. Once they are brought to the Tribunal’s attention, it cannot ignore these serious issues in connection with this procurement on the sole basis that CGI has not conclusively demonstrated that its score and ranking was directly affected.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

42

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

While considering all the circumstances relevant to this procurement, including the factors set out in subsection 30.15(3) of the CITT Act, the

Tribunal comes to the conclusion that, on the facts of this matter, it must recommend a remedy that will ensure fairness to all bidders that took part in this process. For those reasons, the Tribunal finds that the appropriate remedy is to recommend that Canada Post re-evaluate the technical proposals of all six original bidders with a new team of evaluators and that Canada Post’s debriefing and document retention practices and procedures be amended.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

43

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

In the event that the re-evaluation process resulted in a different ranking from the original process, the Tribunal ordered that Canada Post either cancel the original contract awards or award additional master service agreements to the top-ranking proponents in the new evaluation. As this case illustrates, the failure to properly assess information collected during site visits can have a significant detrimental impact on the defensibility of an evaluation process.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

44

Data Centre Tender Triggers Multiple Bid Complaints

CGI Information Systems and Management Consultants Inc. v. Canada Post Corporation

Canadian International Trade Tribunal

The inability to defend the outcome of a procurement process from legal challenge is compounded where institutions fail to maintain proper evaluation records or conduct proper debriefings. This trilogy of determinations therefore serves as a useful reminder to public institutions of the need to ensure that their procurement practices and procedures align with their trade treaty obligations.

Debriefing Duty – Consensus Scoring Record Keeping – Site Visits During Evaluation Process

45

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

In its October 2014 decision in TPG Technology

Consulting Ltd. v. Canada, the Federal Court dismissed a plaintiff bidder’s $250 million lost profit claim against the government of Canada. The October trial decision was the third part in a complex trilogy of legal proceedings that included a September 2011 Federal Court summary dismissal of the bidder’s claim, followed by a July 2013

Federal Court of Appeal reversal that directed the matter to trial.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

46

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

The claim dealt with a federal government procurement process valued at approximately $428 million for the acquisition of information technology engineering and technical support services. TPG, an unsuccessful bidder, launched an action seeking damages against the federal government. TPG originally claimed that PPI Consulting

Ltd., the external consulting firm retained by the government to assist in the evaluation process, was biased against it and lowered its score during consensus scoring sessions.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

47

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

As the September 2011 summary dismissal decision detailed, TPG claimed that the consensus scoring had been arbitrarily applied by PPI, who they claimed had a pre-existing bias against them as a “body shop”:

TPG claims that PPI, the third party facilitator “had a manifest bias against awarding the contract to TPG and disparaged TPG as a ‘body shop’” (see Powell affidavit para 15). The evaluation consisted of a consensus score model whereby the five evaluators would meet to discuss their individual scores and then arrive at a consensus score.

TPG alleges that these consensus scores were arbitrarily applied to unjustifiably reduce TPG’s scores.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

48

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

TPG alleged that the government had selected the consensus scoring method because its high subjectivity allowed personal biases to infiltrate the evaluation. In support of its allegations, the plaintiff pointed to disparaging public remarks attributed to the president of

PPI as evidence that bias had tainted the evaluation process:

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

49

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

The appropriateness and effectiveness of consensus method itself, specifically chosen by PWGSC in an effort to produce the fairest result by ensuring that evaluators are using a consistent understanding of the requirements, is questioned by TPG. During the hearing, counsel for TPG advanced the argument that PWGSC intentionally selected the consensus model, the most subjective model in their view, as a way to allow personal bias and preferences to infiltrate the process.

The bias was one against “body shops” - TPG maintaining that Mr.

Tibbo might have had a prejudice against small companies and “body shops” as Mr. Howard Grant, president of PPI was quoted in an industry publication in 2009, as speaking disparagingly of “body shops.”

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

50

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

With respect to the consensus scoring sessions, the court noted that PPI presided over group discussions to address instances where the five evaluators had arrived at different scores. While the court noted that some errors occurred during PPI’s tabulation of the consensus scores, it also cited affidavit evidence submitted by the individuals who were involved in the process who swore that, contrary to the plaintiff’s allegations, they had not been influenced by anyone to alter TPG’s scores or manipulate the outcome of the evaluation.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

51

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

In its September 2011 summary judgment decision, the

Federal Court rejected TPG’s allegations of impropriety in the evaluation process, finding that the plaintiff had failed to prove its theory of a tainted and biased evaluation.

However, the Federal Court of Appeal disagreed with the

Federal Court’s conclusions, finding that it had misapplied the rule for summary judgment and that there remained issues regarding liability that warranted a full trial.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

52

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

In determining that there remained outstanding issues that warranted a trial, the Federal Court of Appeal also clarified the Supreme Court of Canada’s rule from Double N

Earthmovers v. Edmonton (City) and held that post-award conduct could be relied on as evidence of whether a winning tender was compliant or non-compliant. This point was material to whether there were issues that required a trial since the winning bidder had allegedly planned to use

TPG’s former employees in the performance of the awarded contract.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

53

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

As the Federal Court of Appeal observed, the availability of those employees was far from certain and therefore brought the compliance of the winning tender into question. The matter then proceeded to a full trial, albeit by that point, TPG had abandoned its allegations against the government regarding conflict of interest, negligence, bad faith, misconduct, bias, fraud, unconscionability, inducing breach of contract and economic interference.

TPG also abandoned its allegations that the RFP had been drafted to favour a competing bidder and abandoned claims for punitive damages.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

54

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

At trial, TPG’s lost profit claim rested on the assertions that the government evaluation team had made significant errors in their evaluation that had cost it the contract award. The Federal Court’s lengthy decision considered the issue of court jurisdiction and also considered the fairness of the evaluation process, the compliance of the winning bidder and the issue of damages.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

55

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

The Federal Court ultimately dismissed the claim by declining to take jurisdiction after concluding that the complaint should have been brought before the Canadian

International Trade Tribunal. While the Federal Court acknowledged that the Tribunal does not have exclusive jurisdiction over federal government procurement but shares concurrent jurisdiction with the Federal Court, the

Federal Court found that the remaining issues in TPG’s claim fell squarely within the Tribunal’s expertise. It therefore declined to exercise its jurisdiction over the matter.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

56

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

However, while it dismissed the case on jurisdictional grounds, the Federal Court also considered TPG’s substantive claims and found that the government evaluation committee’s consensus scoring process was flawed. The Federal Court noted that an averaging of the evaluation committee’s individual scores showed a significant divergence in TPG’s scores before and after consensus scoring.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

57

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

In one particular evaluation category, TPG’s average initial score was 80.6 out of 100 but its final consensus score was

49 out of 100. In another category, TPG’s average initial score was 32.8 out of 50 but its final consensus score was 22 out of 50. As the decision noted, confusion arose within the evaluation team about the method of scoring performance metrics. That confusion resulted in the evaluation committee abandoning its individual scores and re-scoring TPG’s proposal collectively. Given the government’s explanation, the

Federal Court found no fairness issues arising out of this departure from the individual scores.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

58

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

However, the Federal Court did find that the evaluation committee was inconsistent in its scoring process since it failed to re-evaluate the winning bidder’s scores by consensus as it had done for TPG’s proposal.

Notwithstanding this finding, the Federal Court ultimately rejected TPG’s claim since it found that the evaluation errors in the two noted categories had had no impact on the ultimate ranking, particularly since TPG failed to provide any evidence regarding unfairness in any of the other seven evaluation categories.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

59

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

The Federal Court also rejected TPG’s assertions that the winning bidder was non-compliant and that it should have been awarded the contract as the highest scoring compliant proponent. The Federal Court therefore found that TPG was not entitled to any lost profits.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

60

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

While the government was ultimately able to defend itself against the $250 million lost profit claim, it was only able to do so after protracted legal proceedings. Irrespective of the final outcome of this controversial case, purchasing institutions should take note that controversial public comments made by their officials and by their external consultants can be used against them in legal proceedings in an attempt to impugn the integrity of an evaluation process through allegations of bias.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

61

Federal Court Rejects $250 Million Lost Profit Claim

TPG Technology Consulting Ltd. v. Canada

Federal Court

Furthermore, when employing consensus scoring, purchasing institutions should ensure that such processes are implemented with a high degree of diligence since: (i) scoring changes arising out of consensus scoring can be subject to a legal challenge; and (ii) tabulation errors or procedural irregularities arising out of such sessions, however innocuous or inadvertent, can be used against the institution to launch protracted legal proceedings and create significant potential legal exposure.

Fair Evaluations – Consensus Scoring – Tender Compliance

62

Negotiated RFPs Remain

Subject to Legal Challenge

By Paul Emanuelli, Procurement Law Office

The past ten years has seen a rapid expansion in the use of flexible negotiated RFPs (“NRFPs”) in the

Canadian public sector as a means of increasing flexibility in the bidding process while reducing the financial risk of lost profit lawsuits. However, as the

February 2014 decision in Rapiscan Systems Inc. v.

Canada (Attorney General) shows, when using flexible formats public institutions must still follow due process rules or face legal challenges that can result in unfair contract award decisions being struck down by the courts.

This article by Paul Emanuelli was previously published in the June 2014 edition of Purchasing b2b magazine.

63

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

A Case Study in Undue Process

If properly drafted, NRFPs operate under traditional contract law rules instead of the high-risk and inflexible fixed-bid “Contract A” tendering model. This enables greater flexibility in evaluating creative solutions and in fine-tuning contract terms to reflect unique solution-based performance terms. It also helps protect against the financial exposures of lost profit claims from losing bidders. However, this does not mean that a public institution can now part ways with due process.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

64

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

No Contract A Not An Out From Legal Challenge

As the recent Federal Court of Canada decision in

Rapiscan Systems Inc. v. Canada (Attorney General) illustrates, running an unreasonable or unfair competition with hidden preferences and providing misleading information to those responsible for making the ultimate contract award decision can get you sued even if you are not in Contract A.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

65

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

Court Strikes Down the Contract Award

In the case, the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

(“CATSA”) issued a non-Contract A solicitation for airport security screening equipment. After submitting an unsuccessful proposal, Rapiscan Systems launched a legal challenge alleging that CATSA had conducted an improper process. The court agreed, granting Rapiscan’s application and declaring that the award to its competitor was invalid, unlawful and unfair. By way of remedy, the court directed CATSA to redo its future procurement process for the required equipment.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

66

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

Fatal Flaws in the Contract Award Process

In its lengthy decision the court found: (a) that the evaluation

“was not a fair or competitive process” since there was “the concealment of minimum requirements and performance standards” which unfairly favoured the applicant’s competitor and constituted bad faith on the part of CATSA;

(b) that CATSA’s management failed to advise its board “that it had derogated drastically from the Contracting Procedures during the procurement process”; and (c) that “management did not provide the Board with accurate information upon which to base its decision” and that this conduct undermined

“the integrity of the government’s tendering processes”.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

67

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

Unfair, Unreasonable and in Bad Faith

Based on these findings, the court determined that the board’s decision “was unfair, unreasonable, made without proper consideration of relevant factors and in bad faith.”

As the Rapiscan case illustrates, public sector procurement remains subject to legal challenge even when the tendering process does not create Contract A.

While lost profit damages were not available as a remedy for the unfair process, the unfairly treated bidder still had legal recourse through the administrative law remedy of judicial review.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

68

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

Long Line of JR Cases Establish Four-Part Test

This remedy gives the courts broad powers, including the ability to strike down government decisions when those decisions constitute an unreasonable exercise of statutory powers. The Rapiscan case is just one example in a long line of recent judicial review judgments that have established the following four-part legal test for reviewing government procurement decisions:

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

69

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

1. Does the Decision Involve a Public Body?

Does the procurement process involve a public institution?

The judicial review remedy only applies to public institutions and does not apply to private sector purchasers.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

70

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

2. Are there Alternative Remedies?

Are there alternative remedies available? If the process is subject to legal challenge based on Contract A lost-profit claims or trade treaty-based challenges at the Canadian

International Trade Tribunal, then the courts may not entertain a judicial review application.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

71

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

3. Was the Award Made Under Statutory Power and

Did the Contract Include Public Interest Elements?

Did the decision involve the exercise of statutory power in a manner that attracts public interest concerns? While the courts will not generally review policy or budgetary decisions, they may review specific procurement decisions made under statutory powers (which captures most public procurement decisions) if the specific procurement decision is significant enough to attract public interest concerns. While the “public interest test” may be met by the size or public nature of the contract, it can also be informed by the gravity of the alleged misconduct.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

72

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

4. Was the Decision Unreasonable?

Was the challenged decision unreasonable? If the court finds that the decision was unfair, absurd, made in bad faith, or made arbitrarily or in a procedurally unsound manner then it may order a reconsideration or strike down the decision.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

73

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

Due Process a Core Duty

As recent judicial review decisions illustrate, public institutions cannot escape judicial scrutiny simply by contracting out of Contract A. In government procurement, the duty to follow due process is an inherent condition of exercising statutory powers. Using NRFPs and other flexible formats may offer some significant advantages, but breaking the rules with impunity is not one of them.

Negotiated RFPs and Judicial Review

74

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

In its February 2014 judgment in Inzola Group Ltd. v.

Brampton (City), the Ontario Superior Court of Justice dismissed a motion brought by a winning bidder seeking to limit the disclosure of business information it submitted during a bidding process. The case involved an RFP for the construction of public buildings, including new municipal offices and a public library, as part of a downtown renewal project in Brampton, Ontario. The contract was awarded to Dominus Capital Corporation.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

75

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

Inzola Group, an unsuccessful competing bidder, brought an action against Brampton claiming $27.5 million in damages and an additional $1 million in punitive damages. The material submitted by Dominus during that bidding process was sought by Inzola as part of its lawsuit. Dominus brought the motion for a protective order that would limit the public distribution of the information in question.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

76

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

As part of its claim, Inzola challenged Brampton’s requirement that prospective bidders sign a confidentiality agreement during the bidding process, alleging that its bid was ultimately disqualified since it refused to accept the process restrictions imposed by the non-disclosure agreement. In its defence, Brampton denied Inzola’s allegations and maintained that the confidentiality protocol was required to prevent lobbying of elected officials during the bidding process.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

77

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

Given the factual issues that had to be addressed in the proceedings, Brampton was ordered to provide Inzola certain documents that had been collected from Dominus during the bidding process. Dominus challenged the disclosure, maintaining that it was assured that the information it provided during the bidding process would be kept confidential. Dominus also asserted that the public disclosure of the information would cause it serious financial harm since its competitive position in the market would be prejudiced by allowing competitors access to its financial information.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

78

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

It argued that because it was a privately held company, this information was not otherwise publicly known. While

Dominus agreed to allow Inzola to have access to the information, it sought a protective order to restrict access to that information by others or use by Inzola for any purposes other than the legal proceedings. The court ultimately rejected the request for a protective order, finding that Dominus had not established that the information in question was particularly sensitive.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

79

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

In support of its conclusion, the court noted that the information did not appear to be treated as confidential in the industry and that Dominus and Inzola did not appear to be true competitors. The court concluded that Dominus was unable to show how the disclosure of the information would result in a serious risk to Dominus and that, on balance, the public interest in the transparency of legal proceedings prevailed over any such potential risk.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

80

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

The court therefore dismissed the motion, thereby compelling the disclosure of the requested information to

Inzola. To balance that disclosure, the court also ordered that Brampton disclose to Dominus the equivalent documents that Inzola had submitted during that contested bidding process.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

81

Court Orders Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder

Inzola Group Ltd. v. Brampton (City)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

As this case illustrates, the confidentiality protocols that are established during a competitive bidding process will not necessarily shield information from the disclosure duties that arise in post-bid legal disputes. While preaward confidentiality is often required to protect the integrity of the bidding process, public interest considerations tend to favour transparency in the postaward phase of that process, particularly when legal challenges are launched against the contract award decision.

Disclosure Duty – Disclosure of Winning Bid to Losing Bidder in Pre-Trial Discoveries

82

Court Orders Disclosure of Contract Award Information

HKSC Developments L.P. v. Infrastructure Ontario

Ontario Superior Court of Justice – Divisional Court

In its November 2014 judgement in HKSC Developments

L.P. v. Infrastructure Ontario, the Ontario Superior Court of

Justice ordered the disclosure of information contained in a contract awarded by Infrastructure Ontario to HKSC

Developments L.P. notwithstanding HKSC’s objections to that disclosure. The dispute arose over a public access request for information contained in a contract between

Infrastructure Ontario and HKSC for the development, design, construction and partial financing of highway service centres on Highways 400 and 401 in Ontario that was awarded pursuant to a competitive bidding process.

Disclosure Duty – Public Access Request – Disclosure of Information in Awarded Contract

83

Court Orders Disclosure of Contract Award Information

HKSC Developments L.P. v. Infrastructure Ontario

Ontario Superior Court of Justice – Divisional Court

When the parties could not agree on the amount of information that could be disclosed, the matter ultimately escalated to the Ontario Information and Privacy

Commissioner pursuant to Ontario’s Freedom of

Information and Protection of Privacy Act. This resulted in an adjudicator’s order to disclose most of the requested information. HKSC took issue with that order, arguing that the information was protected under the confidential business information exemption in the Act.

Disclosure Duty – Public Access Request – Disclosure of Information in Awarded Contract

84

Court Orders Disclosure of Contract Award Information

HKSC Developments L.P. v. Infrastructure Ontario

Ontario Superior Court of Justice – Divisional Court

However, the adjudicator ruled that information in question did not fall under the relevant statutory exemption since the information had not been “supplied in confidence” to the government but had been produced in the course of extensive negotiations between HSKC and the government institution. The court upheld the adjudicator’s disclosure order on that basis. As this case illustrates, a party that opposes the disclosure of information requested under public access laws has the onus of establishing why that information should be protected.

Disclosure Duty – Public Access Request – Disclosure of Information in Awarded Contract

85

Court Orders Disclosure of Contract Award Information

HKSC Developments L.P. v. Infrastructure Ontario

Ontario Superior Court of Justice – Divisional Court

In this instance, the contractor failed to meet that test since the information created in the course of post-bid negotiations between the contractor and the government agency did not fall within the meaning of “information supplied in confidence”. Rather, that information was considered to be jointly created by the parties during negotiations, and public interest considerations favoured the disclosure of that information to better ensure the transparency of the government contracting process.

Disclosure Duty – Public Access Request – Disclosure of Information in Awarded Contract

86

Paul Emanuelli’s

Seven Stages of Precision Drafting

1

2

Material

Disclosures

3

Initial Mapping

Statement

Eligibility

Requirements

4

Detailing

Requirements

Ranking &

Selection Criteria

5

6

Horizontal Integration

Aligning Requirements, Ranking Criteria and Pricing Form

Legal

Agreement

Initial Mapping

Statement

Detailing

Requirements

7

Vertical Integration

Aligning Legal Agreement,

Requirements and

Pricing Form

Pricing Form

87

Warning:

Do Not Proceed Before Completing Project Design

1

2

Material

Disclosures

3

Initial Mapping

Statement

Eligibility

Requirements

4

Detailing

Requirements

Ranking &

Selection Criteria

5

6

Horizontal Integration

Aligning Requirements, Ranking Criteria and Pricing Form

Legal

Agreement

Initial Mapping

Statement

Detailing

Requirements

7

Vertical Integration

Aligning Legal Agreement,

Requirements and

Pricing Form

Pricing Form

88

Design Overview

ABC Sequencing: (A) Design (B) Drafting (C) Assembly

1

2

Material

Disclosures

3

Initial Mapping

We Buying?

Detailing

Eligibility

Evaluation

Plan?

4

Requirements

Ranking &

Selection Criteria

5

6

Horizontal Integration

Aligning Requirements, Ranking Criteria and Pricing Form

Requirements

What is the

Pricing Form

Format?

7

Vertical Integration

Pricing Form

Format?

89

Tender

Planning

Hub

What Are

We

Buying?

What is the

Tendering

Format?

How Do

We

Assemble the Final

Contract?

What is the

Evaluation

Plan?

What is the

Pricing

Format?

90

A. Design

B. Drafting

C. Assembly

91

Budget

Approval

Internal Governance Roadmap

Conditional

Expenditure

Approval

Expenditure

Approval

1.

Project

Planning

2.

Procurement

Streaming

Business

Units

Business

Plan

Requirements and

Specifications

Pricing

Structure

Evaluation

Plan

Stream

Selection

Format

Selection

Business

Units

Pre-

Qualification

Framework

Corporate

Agreements

Invitational

Competition

Open

Competition

Business

Unit

Direct Award

3.

Document

Assembly

4.

Competition

5.

Contract

Formalization

6.

Post-Award

7.

Contract

Management

Procurement

RFX

Document

Contract

Legal Terms

Requirements and

Specifications

Pricing

Structure

Evaluation

Plan

Procurement

Issuing of

Competitive

Bid

Document

Posting of

Q&As and

Addenda

Bid Receipt

Procurement

Supplier

Selection

Letter

Business

Units

Bid

Evaluations

Legal and

Business

Units

Contract

Finalization

Procurement

Notice of

Award

Business

Units

Performance

Tracking and

Payment

Issue

Management

Business

Units

Debriefing Legal and

Procurement

Bidder

Barring

Process

Legal and

Procurement

Bid Protest

Process

92

© Paul Emanuelli, 2011

Tendering Templates

Procurement Playbook Menu

93

Tendering Templates

Procurement Playbook Menu

Invitation to Tender

No-Negotiation RFP

Consecutive Negotiation/Rank-and-Run RFP

Concurrent Negotiation/BAFO RFP

Invitational Request for Quotation

Open Request for Quotation

Request for Information

Request for Supplier Qualifications – Prequalification Version

Request for Supplier Qualifications – Master Framework Version

94

Procurement

Playbook

PQ

IEI

ITT

Prequalification

Zone

PQ RFQ

RFI

PQ

RFP

RFI

PQ

Consecutive

Negotiation

RFP

Market

Research Zone

PQ

Competitive

Zone

Contract

Formation

Zone IEI

PQ

Direct

Award

Concurrent

Negotiation

RFP

RFI

Market

Research Zone

SWAT Team Transactional Deployment

Focuses on the Five Core Questions

1. What are we Buying?

Requirements and Material Disclosures

2. What is the Pricing Structure?

Stipulated Sum or Time and Materials

3. What is the Evaluation Plan?

Low Bid or High Score

4. What are the Contract Terms?

Predefined or established through Dialogue

5. What is the Appropriate Tendering Template?

The Procurement Playbook

96

Tender

Planning

Hub

What Are

We

Buying?

What is the

Evaluation

Plan?

How Do

We

Assemble the Final

Contract?

What is the

Pricing

Format?

97

How Do We Assemble the Contract?

Picking Between Prefabrication and Post-Bid Assembly

Project teams can’t afford to go into cruise control and ignore the contract assembly process. This segment will explore the turning points for proper contract design and help you pick between pre-fabrication or post-bid dialogue as the preferred method for aligning your project specifications and pricing grid with appropriately tailored legal terms and conditions.

98

Legal

Agreement

Initial Mapping

Statement

Detailing

Requirements

Pricing Form

The Legal Agreement

7

Vertical Integration

Aligning Legal Agreement,

Requirements and

Pricing Form

The proper final assembly of a procurement document requires the vertical integration of the statement of requirements and the pricing structure with the terms and conditions of the legal agreement.

Purchasing institutions should ensure that they properly integrate all of the document components together with a legal agreement that incorporates the business requirements and payment terms of the contract.

99

1

2

Material

Disclosures

3

Initial Mapping

Statement

Eligibility

Requirements

4

Detailing

Requirements

Ranking & 5

Selection Criteria

6

Horizontal Integration

Aligning Requirements, Ranking Criteria and Pricing Form

Legal

Agreement

Initial Mapping

Statement

Detailing

Requirements

7

Vertical Integration

Aligning Legal Agreement,

Requirements and

Pricing Form

Pricing Form

7. The Legal Agreement aims at vertical integration by tying together the requirements and pricing structure with the legal terms and conditions that govern contract performance.

100

The Legal Agreement

Vertical Integration

The failure to properly align all of the critical contract components can undermine the certainty of terms and can cause significant business and legal exposures.

101

Laying the Foundation of Contract Design

By Paul Emanuelli, Procurement Law Office

To properly leverage their purchasing power and effectively manage their supply chain, purchasing organizations need to proactively integrate contract design concepts into their procurement cycles.

This article by Paul Emanuelli was published in the October 2013 edition of

Purchasing b2b magazine and is extracted from the Accelerating the Tendering Cycle 102

Contract Design

The Four Cornerstones

This article will introduce the four cornerstones of contract design: (i) contract anatomy; (ii) contract architecture; (iii) contract assembly; and (iv) contract award; and will explain how they serve as the foundation for effective contract management.

103

Contract Design

Contract Anatomy

Purchasing professionals need to understand the contents of their contracts at an organic level. They need to dissect the terms and conditions and understand how the various components should work as part of a living agreement between the contracting parties. The basic organs of any properly designed procurement contract include performance terms and payment provisions.

104

Contract Design

Contract Anatomy

The performance terms should clearly define the requirements, performance standards, warranties and delivery schedules.

The payment provisions should establish payment structures and schedules and clearly connect those components to the performance terms.

This basic DNA of contractual anatomy serves as the foundation onto which more specialized terms can then be added to adapt the procurement contract to the specific industry and particular transaction.

105

Contract Design

Contract Anatomy

These specialized terms can include, among other things, change control provisions, confidentiality clauses, insurance and indemnity terms, limitation of liability clauses, dispute resolution and termination protocols, and document retention and audit provisions. Understanding basic and advanced contract anatomy helps to avoid complicating contracts with the dead weight of unnecessary provisions.

106

Contract Design

Contract Architecture

The components of a contract can be housed in different structures. Some contract architectures are designed for speed, others for long-term endurance. The most evolved architectures synthesize speed and endurance with multimodule formats that allow purchasers to lock down standard terms while permitting the rapid incorporation of more complex components as required. Organizations need to direct their purchasing into appropriate format streams.

107

Contract Design

Contract Architecture

Proper contract design takes pressure off of the system by allowing purchasers to direct standard “one-time delivery” transactions into rapid use purchaser order formats while also identifying situations that call for more complex legal agreement formats. It also enables the implementation of user-friendly multi-module formats that can help to quickly navigate the middle ground between these two extremes.

108

Contract Design

Contract Assembly

Contract assembly is the third critical cornerstone of contract design. It takes skill, judgement and experience to properly assess the specific situation and incorporate the necessary elements of contract anatomy into the appropriate contractual architecture.

109

Contract Design

Contract Assembly

Some situations are more self-evident than others. While a one-time delivery of a standard commodity can often be handled through simplified purchase order terms, a fifteen-year outsourcing deal will typically require a formal legal agreement with a complex set of tailored schedules.

110

Contract Design

Contract Assembly

These conceptual extremes may be easy to identify, but it’s the unclear middle ground that often leaves purchasers bogged down in a contractual no man’s land.

It’s in this legal grey zone that proper contract design can bring the greatest gains to the purchasing institution through the implementation of a contract assembly process that enables the rapid creation of modularized contracts tailored to the nuances of the specific industry and adapted to the requirements of the specific good or service.

111

Contract Design

Contract Award

There’s no use having a perfectly assembled contract that no one will sign.

Since it takes two to contract, purchasing organizations should incorporate commercially reasonable terms into their contract design process. Building a sustainable contractual relationship, particularly with strategically significant suppliers, often requires the precision of a scalpel, rather than the blunt force of a “standard form” hammer.

112

Contract Design

Contract Award

While an adversarial “winner-take-all” approach may be suited for certain courtroom situations, getting mired in a

“battle of the forms” with your suppliers and their lawyers will only lead to purchasing gridlock.

To avoid unnecessary legal entanglements, the right starting point is to establish a proper contract design process that allows purchasing professionals to quickly adapt to the circumstances, identify real deal-breakers, and distinguish fundamental terms from the nuisance clauses that tend to unnecessarily bog down the contracting process.

113

Contract Design

Implementing Contract Design

Given the current economic conditions, purchasing professionals are under increasing pressure to find efficiencies and create competitive advantages for their organizations.

Those purchasing institutions that properly adapt to today’s purchasing challenges by integrating contract design concepts into their procurement cycle will be better positioned to survive and flourish in our increasingly competitive marketplace.

114

Integrating a Legal Agreement

(Vertical Integration)

Typical

Commercial Terms

Industry Specific

Terms

Project Specific

Adaptations

Business and

Technical

Requirements

115

Pricing Form

Integrating a Legal Agreement

Industry Specific Terms

Typical

Commercial Terms

Project

Specific

Adaptations

Pricing Structure

Business and

Technical

Requirements

116

Integrating a Legal Agreement

Industry Specific Terms

Typical

Commercial Terms

Project

Specific

Adaptations

Warning: Legal Overload

Reject Fixed-Form Contract!

Deploy Negotiated Format

Pricing Structure

Business and

Technical

Requirements

117

Fixed-Bid Contract A Tendering

1

2

Material

Disclosures

3

Initial Mapping

Statement

Eligibility

Requirements

4

Detailing

Requirements

Ranking & 5

Selection Criteria

6

Horizontal Integration

Aligning Requirements, Ranking Criteria and Pricing Form

Legal

Agreement

Initial Mapping

Statement

Detailing

Requirements

Pricing Form

7

Vertical Integration

Aligning Legal Agreement,

Requirements and

Pricing Form

7. Contract Assembly occurs prior to going to market.

Evaluated bid price is incorporated into final awarded contract.

118

Negotiated RFP Formats

1

2

Material

Disclosures

3

Initial Mapping

Statement

Eligibility

Requirements

4

Detailing

Requirements

Ranking & 5

Selection Criteria

6

Horizontal Integration

Aligning Requirements, Ranking Criteria and Pricing Form

Legal

Agreement

Initial Mapping

Statement

Detailing

Requirements

Pricing Form

7

Vertical Integration

Aligning Legal Agreement,

Requirements and

Pricing Form

7. Contract Design occurs prior to going to market. Final contract assembly occurs after selecting the top-ranked proponent and incorporating the bid price and other performance related content from the evaluated proposal.

119

Provision

Interpretive

Provisions

Nature of

Relationship

Performance

Provisions

Payment

Provisions

Confidentiality

Intellectual

Property

Indemnity and

Insurance

Termination

Legal Agreement Worksheet

Construction Simple

Commodity

One Time

Delivery

Consulting

Services

Technology Major Project

120

Paul Emanuelli © 2014

Consecutive Negotiation RFPs

Rank-and-Run Process

Non-Contract A Negotiated RFP

RFP Issued

Evaluation Establishes

Proponent Rankings

RFP

End Requirements

Process Rules

Evaluation Criteria

Standard Agreement or Term Sheet

(Optional)

• Based on prescribed evaluation criteria established to identify best supplier at best price.

•Evaluation can include assessment of proponent comments on Standard

Agreement or Term

Sheet or assessment of proponent’s proposed agreement terms.

Initial Proponent

Ranking

Negotiation

(Time Limited)