n=10

advertisement

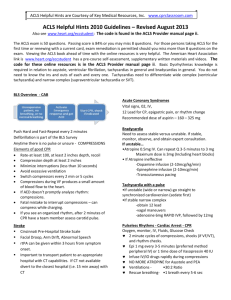

The field of resuscitation has been evolving for more than two centuries [ 1 ]. The Paris Academy of Science recommended mouth-to-mouth ventilation for drowning victims in 1740 [ 2 ]. In 1891, Dr. Friedrich Maass performed the first documented chest compressions on humans [ 3 ]. The American Heart Association (AHA) formally endorsed cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in 1963, and by 1966, they had adopted standardized CPR guidelines for instruction to lay-rescuers Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) guidelines have evolved over the past several decades based on a combination of scientific evidence of variable strength and expert consensus. The American Heart Association (AHA) developed the most recent ACLS guidelines in 2010 using the comprehensive review of resuscitation literature performed by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Guidelines are reviewed continually, but are formally released every five years, and published in the journals Circulation and Resuscitation PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT Excellent basic life support and its importance Excellent cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and early defibrillation for treatable arrhythmias remain the cornerstones of basic and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS). Although the 2010 American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for ACLS (2010 ACLS Guidelines) suggest several revisions, including medications, electrical therapy, and monitoring, . We emphasize the term “excellent CPR” because anything short of this standard does not achieve adequate cerebral and coronary perfusion In the past, clinicians frequently interrupted CPR to check for pulses, perform tracheal intubation, or obtain venous access. The 2010 ACLS Guidelines strongly recommend that every effort be made NOT to interrupt CPR; other less vital interventions (eg, tracheal intubation or administration of medications to treat arrhythmias) are made either while CPR is performed or during the briefest possible interruption. Interventions that cannot be performed while CPR is in progress (eg, defibrillation) should be performed during brief interruptions at two minute intervals (after the completion of a full cycle of CPR) Studies in both the in-hospital and prehospital settings demonstrate that chest compressions are often performed incorrectly, inconsistently, and with excessive interruption . Chest compressions must be of sufficient depth (at least 5 cm, or 2 inches) and rate (at least 100 per minute), and allow for complete recoil of the chest between compressions, to be effective. A 30 to 2 compression to ventilation ratio (one cycle) is recommended in patients without advanced airways ventilations at 8 to 10 per minute are administered if an endotracheal tube or extraglottic airway is in place Resuscitation team management Two principles provide the foundation for CRM(Crisis Resource Management): leadership and communication The team leader should avoid performing technical procedures the team leader may be required to perform certain critical procedures. In these situation When the team leader determines the need to perform a task, the request is directed to a specific team member, ideally by name In CRM, communication is organized to provide effective and efficient care Initial management and ECG interpretation In the 2010 ACLS Guidelines, circulation has taken a more prominent role in the initial management of cardiac arrest. (C-A-B) Rescue breathing is performed after the initiation of excellent chest compressions and definitive airway management may be delayed if there is adequate rescue breathing without an advanced airway in place In the non-cardiac arrest situation, the other initial interventions for ACLS include administering oxygen, establishing vascular access, placing the patient on a cardiac and oxygen saturation monitor, and obtaining an electrocardiogram Unstable patients must receive immediate care, even when data are incomplete or presumptive Stable patients require an assessment of their electrocardiogram in order to provide appropriate treatment consistent with ACLS guidelines Is the rhythm fast or slow? Are the QRS complexes wide or narrow? Is the rhythm regular or irregular AIRWAY MANAGEMENT DURING ACLS Ventilation is performed during CPR to maintain adequate oxygenation and to eliminate carbon dioxide, although this is less important. Nevertheless, during the first few minutes following sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), oxygen delivery to the brain is limited primarily by reduced blood flow. Therefore, in adults, the performance of excellent chest compressions takes priority over ventilation during the initial period of basic life support. In settings with multiple rescuers or clinicians, ventilations and chest compressions are performed simultaneously we know that hyperventilation is harmful, as it leads to increased intrathoracic pressure, which decreases venous return and compromises cardiac output ACLS Guidelines recommend 8 to 10 breaths per minute with an advanced airway in plac but we believe 6 to 8 breaths are adequate Elements of BLS (4 of 8) The System Components of CPR (1 of 2) Source: American Heart Association Coronary Perfusion Pressure (mm Hg) Survival is related to arterial pressures generated by chest compressions 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Not the pH Not the oxygen content It’s all about Coronary Perfusion Pressure ! 24-hour Survivors Resuscitated But Expired Could Not Resuscitate Survival better with compression rate of 100 – 120 compressions/minute Mean rate, ROSC group 90 ± 17 * Number of 30 sec segments 210 p=0.003 Mean rate, no ROSC group 79 ± 18 * 180 150 No ROSC ROSC 120 90 60 30 0 10-20 20-30 30-40 40-50 50-60 60-70 70-80 80-90 90-100 100-110 110-120 Chest compression rate (min-1) Abella et al, 2005 >120 Shock success, percent Shock success by compression depth p=0.02 n=10 n=13 n=14 n=5 Compression depth, inches Edelson et al, 2006 Shock success, percent Shock success by pre-shock pauses 100 80 90% 60 p=0.003 64% 55% 40 20 10% 0 ≤10.3 (n=10) 10.5-13.9 (n=11) 14.4-30.4 (n=11) ≥33.2 (n=10) Pre-shock pause, seconds Edelson et al, 2006 Assessing ABCs (14 of 18) Assessing ABCs (18 of 18) When to Stop BLS (1 of 2) • Once you begin CPR, continue until (STOP acronym): – S Patient Starts breathing and has a pulse – T Patient is Transferred to another trained responder – O You are Out of strength – P Physician directs to discontinue When to Stop BLS (2 of 2) • “Out of strength” does not just mean tired, but physically unable to continue. ACLS Survey • A––Airway • ■ Maintain patent airway. • ■ Maintain proper head position. • ■ Use oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway if indicated. • ■ Use advanced airway if indicated (laryngeal mask airway [LMA], • laryngeal tube, esophageal-tracheal tube, endotracheal tube [ET]). • ■ B––Breathing • ■ Perform bag-mask ventilation. • ■ Provide supplemental oxygen. • ■ Monitor adequacy of ventilation and oxygenation. • • Ensure adequate chest rise. • • Use CO2 detector or quantitative waveform capnography. • • Measure oxygen saturation. • • Avoid excessive ventilation. ACLS Survey • ■ C––Circulation • ■ Provide high-quality CPR. • ■ Monitor cardiac rhythm. • ■ Initiate prompt defi brillation/cardioversion when indicated. • ■ Establish IV/IO access. • ■ Administer medication when indicated. • ■ Administer volume resuscitation when indicated. • ■ Assess for ROSC. • D––Differential Diagnosis: • ■ Identify and treat potentially reversible causes. Hypokalemia Hypokalemia should be suspected in patients on diuretics, those with a recent history of vomiting or diarrhea, and malnourished patients, especially alcoholic and elderly patients. ECG: flattened T waves and prominent U waves, in leads V2–V3, ST depression, QT prolongation, There could be increased PVCs,(NSVT). Emergent treatment for a potassium level <2.5 mEq/L or signifi cant ventricular ectopy includes potassium repletion with potassium chloride IV, maximum 20 mEq/hr by central line, or 10 mEq/hr by peripheral line. Hyperkalemia should be suspected in patients with a history of renal failure, diabetes with hyperglycemia, recent dialysis, metabolic acidosis, or use of potassium-sparing medications such as spironolactone, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin-receptor blockers ECG:Tall&peaked T waves; small P waves or loss of P waves; and QRS widening. Patients are at risk for fatal arrhythmias. With severe hyperkalemia, patients may present in cardiac arrest with sine waves (the P wave disappears and the QRS and T wave merge in an oscillating pattern) on the ECG. Emergent treatment includes administration of IV calcium chloride to stabilize myocardial cell membranes, and IV sodium bicarbonate to shift potassium out of the vascular space and into body cells. In the absence of cardiac arrest, other treatments include IV insulin plus glucose or nebulized albuterol to shift potassium into cells, and IV furosemide, sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate), or dialysis to increase potassium excretion. Hypovolemia The ECG may be normal with a rapid heart rate. Resuscitation measures in cardiac arrest will be ineffective unless intravascular volume is replaced rapidly. Hypoxia: Hypoxia (low arterial and tissue oxygen) should be suspected in patients with a history of asthma, COPD, or CHF. Causes of hypoxia include airway obstruction, pulmonary embolus, pulmonary edema, signifi cant pleural effusions, pneumothorax or hemothorax, severe asthma attack, COPD exacerbation, or respiratory infection. Hypothermia: A central body temperature of 34°–36°C (93.2°–96.8°F) is mild hypothermia; 30°–34°C (86–93.2°F) is moderate hypothermia; <30°C (<86°F) is severe hypothermia. ECG: sinus bradycardia with prolonged PR and QT intervals ,& a J or Osborne wave may be noted,in inf.leads&V4-V6 ,VT,VF Mild hypothermiawarm room Moderate hypothermiahot-water bottles Severe hypothermia warm IVfl uids and warm oxygen. Hydrogen ion (acidosis) Tension pneumothorax Thrombosis (pulmonary or coronary) Tamponade Toxins . . . 37 Multifocal Atrial Tachycardia (MAT) 38 39 SVT 40 41 NSRSVT 42 43 Atrial Flutter (A-flutter) 44 45 AF 46 47 Junctional Arrhythmias 48 49 Idioventricular Rhythm 50 51 Premature Ventricular Contraction: Multiform 52 53 SMVT 54 55 SPMVT 56 57 TDP 58 59 VF 60 61 CHB 62 63 Mobitz II 64 65 Mobitz I 66 Overview of ACLS Pharmacology and Update on New ACLS Guidelines Objectives • Pharmacists should be able to identify: Why? …we use an agent When? …to use an agent How? …to use an agent What? ...to watch for • To familiarize the pharmacist with the ACLS algorithms • To help the pharmacist become comfortable with the crash cart • To introduce the needless delivery system Routes of Administration Intravenous • Preferred route Endotracheal · · · · 2-2.5 X’s IV dose in 10ml volume Each dose is followed by 10 ml NS flush down the ET tube (Ex. epinephrine, atropine, lidocaine, diazepam, naloxone) Absorption occurs at alveolar capillary interface Intraosseous (active bone marrow) · Pediatric patients without IV access Other: Sublingual, intracardiac, IM, SC (poor absorption) Epinephrine WHY? • Natural catecholamine with and ß-adrenergic agonist activity • Results in: • flow to heart and brain • SVR, SBP, DBP • electrical activity in the myocardium & automaticity ( success with defibrillation) • myocardial contraction (for refractory circulatory shock (CABG)) • increases myocardial oxygen requirements • Primary benefit: -vasoconstriction • ß-adrenergic activity controversial b/c myocardial work WHEN? • VF/VT, asystole, PEA, bradycardias Epinephrine HOW? • High dose versus standard dose? • Higher ROSC with high dose, but no change in survival • High doses may exacerbate postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction Recommendations: • • • • Class I: 1 mg IV q 3 - 5 min Class IIb: 2-5mg IVP q3-5min, or 1mg-3mg-5mg Class Indeterminate: high-dose 0.1mg/kg IVP q3-5min Infusion for HR & BP (IIb) • 1mg in 250ml NS or D5W - infuse @ 1-10 mcg/min • ET Dose=2-2.5 times IV dose What to watch for? • Tachycardia, hypertension, myocardial ischemia, acidosis Pulseless Ventricular Fibrillation or Tachycardia • In ACLS, always assume VF - most common • 85%-95% of survivors have VF • Survival dependant on early defibrillation • Medications indicated only after 3 failed shocks Drugs for VF/PVT • Epinephrine - Why? How? What? • Vasopressin - Why? How? What? • Amiodarone • Magnesium • Procainamide • Lidocaine Drugs Used to Improve Cardiac Output and Blood Pressure Sodium Bicarbonate WHY? decreases drugs Enhances K+ shift intracellularly, buffers acidosis, toxicity of TCA’s, increases clearance of acidic WHEN? Class I - hyperkalemia Class IIa - bicarbonate-responsive acidosis metabolic acidosis secondary to loss of bicarb (renal/GI); overdoses (TCAs, phenobarbital, aspirin) Class IIb - protracted arrest in intubated patients Class III - hypoxic lactic acidosis HOW? 1 mEq/kg IVP, 0.5mEq/kg q10 min prn WHAT? May worsen outcome if not intubated/ventilated. Metabolic alkalosis, decreased O2 delivery to tissues, hypokalemia, CNS acidosis, hypernatremia, hyperosmolarity Tachycardia - Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter 4 Clinical Features: • Unstable? • Impaired cardiac function? • WPW? • Duration? <48h, or > 48h? • Focus - treat unstable patients urgently • Control ventricular response convert anticoagulate Drugs Used in Afib/AFlutter • • • • • • Calcium channel blockers Beta-blockers Digoxin Amiodarone Procainamide Flecainide (IV form in ACLS -not available in US) • Propafenone (IV form in ACLS -not available in US) • Sotalol (IV form in ACLS -not available in US) Stable Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Preserved Cardiac Function NOTE! May go directly to cardioversion Medications: any one •Procainamide (IIA) •Sotalol (IIA)* •Amiodarone (IIB) •Lidocaine (IIB) *Not yet available in the US. Impaired LV EF<40% or CHF Amiodarone (IIB) •150 mg IV bolus over 10 min •may repeat 150mg q1015min or start infusion OR Lidocaine (IIB) •0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg IV push Then use •Synchronized cardioversion Narrow-Complex Supraventricular Tachycardia • Vagal stimulation • Adenosine • Junctional • 1. EF > 40% - Amiodarone, B-blocker, CCB • 2. EF <40%, CHF - Amiodarone • PSVT • EF>40% - CCB, BB, digoxin, DC cardioversion (procainamide, amiodarone, sotalol) • EF<40%, CHF - DC cardioversion; digoxin, amiodarone, • MAT • EF>40% -No DC cardioversion; CCB, BB, amiodarone • EF<40% -No DC cardioversion; amiodaonre, diltiazem Wide-Complex Tachycardia • “Wide” …. Prolonged QRS or QRST interval • HR > 120 bpm (ex. VT, sinus tachycardia, A.flutter) • Establish diagnosis - 12-lead ECG • Adenosine if SVT- slows AV conduction. Short-lived hypotension • Amiodarone (IIa) normal LV function • Amiodarone (IIb) impaired LV function • Procainamide (IIa)- terminates SVT due to altering conduction across accessory pathways • Lidocaine if VT • Sotalol, propafenone, flecainide Pulseless Electrical Activity • PEA… no pulse with + electrical activity (not VF/VT) • Reversible if underlying cause is reversed (5 H’s, 5 T’s) • Hypovolemia, hypoxia, hydrogen ion (acidosis), hyper/hypokalemia, hyper/hypothermia • Tablets, tamponade, tension pneumothorax, thrombosis (ACS), thrombosis (PE) Intervention Comments/Dose Problem intervene Search for the probable cause and (HCO3) Epinephrine 1 mg IV q3-5 min. Atropine With slow heart rate, 1 mg IV q3-5 min. (max. dose 0.04 mg/kg) Atropine WHY? Anticholinergic/direct vagolytic Enhances sinus node automaticity and AVN conduction WHEN? PEA, symptomatic sinus bradycardia, asystole, HOW? Bradycardia: 0.5 -1 mg IV q3-5 min Asystole: 1 mg IV q 3-5 min Max = 0.04 mg/kg or 3 mg ET Dose=1-2mg diluted in 10ml Paradoxical bradycardia with insufficient dose (<0.5mg) WHAT? Tachycardia; 2nd or 3rd degree AV block (paradoxical slowing may occur), MI (may worsen ischemia/HR) Bradycardia “All Patients Deserve Empathy” (The sequence reflects interventions for increasingly severe bradycardia) • • Absolute or relative Serious signs and symptoms (CP, hypotension, mental status changes) Mnemonic Intervention Comments/Dose All Atropine 0.04 mg/kg) 0.5-1.0 mg IVP q 3-5 min (max 0.03- Patients S/S Pacing Use Transcutaneous Pacing if severe Deserve Dopamine 5-20 µg/kg/min. Empathy Epinephrine 2-10 µg/min. Dopamine WHY? NE precursor Stimulates DA, & -adrenergic receptors (dose-related) Want -stimulation, for bradycardia-induced hypotension WHEN? Hypotension/shock HOW? renal: 2 - 5 mcg/kg/min cardiac: 5 - 10 mcg/kg/min (B1 & alpha) vascular: 10 - 20 mcg/kg/min (alpha) Preparation: 400 mg/250 ml D5W or NS WHAT? Tachycardia, tachyphylaxis, proarrhythmic If requiring > 20mcg/kg/min consider adding NE ACLS Algorithms Asystole • Consider possible causes and treat accordingly (ex.hypoxemia, hyper/hypokalemia, acidosis) Acronym “TEA” T Transcutaneous Pacing (TCP) (Class IIb) Only effective with early implementation along with appropriate interventions and medications E Epinephrine 1 mg IV q3-5 min. A Atropine 1 mg IV q3-5 min. (max. dose 0.04 mg/kg) • Discourage shocking due to excess parasympathetic discharge Acute Myocardial Infarction • “Call first, call fast, call 911” • Oxygen 4L/min?? • NTG SL, paste or spray; if BP > 90 mm Hg, IV NTG • Morphine IV • ASA PO (I) • Thrombolytics? (I) - within 6 hours of symptoms, (II) if > 6hr • IV heparin Or Enoxaparine • B-blockers • Clopidogrel • Captoprile Drugs Used to Improve Cardiac Output and Blood Pressure Dobutamine Action: B1- adrenergic activity Indication: Inotrope in heart failure/hypotension Dose: 2 - 20 mcg/kg/min Preparation: 250 mg/250 ml D5W or NS Caution: ischemia tachyarrhythmias,worsens myocardial