Surviving the Research Paper

advertisement

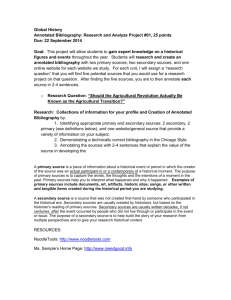

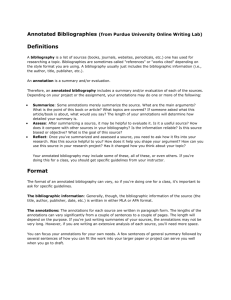

Surviving the Research Paper A Guide and Study Manuel Fear and Loathing It is with great fear that students come to the research paper. And with much loathing do they leave it. But leave it, we hope, better writers. “Abandon hope all ye who enter here…” --Dante, Inscription at the gates of Hell What am I going to do? Not a simple history or book report (“Important Rivers of Africa”) Not merely an argumentative essay where you are objective, and present critical judgments in a formal argument (“An Interpretation of Women in Shakespeare’s King Lear”). Next level of analysis: Read a primary text (Catcher in the Rye) and manage textual support from it to defend a critical judgment about it BUT ALSO present secondary material, that is, commentary and analysis written by other scholars. Three Criteria to Keep in Mind Personal Interest: Seek out a topic that appeals to you. Become an “authority.” Live it! Own it! 2. Appropriateness: Make sure your topic has depth to it and there’s sufficient secondary material to back up claim. 3. Uniqueness: Choose “road less traveled.” 1. The Topic What aspect of the text is worthy of your time and effort? Several places to look for topic – Your Interests: What situations, characters, problems, settings, and images catch your eye. What about book appeals to your own experience? The Primary Source: What problems arise in the text? Symbols, metaphors, structure, etc. Preliminary Research: Sometimes, in research, a topic is found… Standard Categories of Literary Research Character study: Symbolic/image study: figurative language? How used? Why? Thematic study: What is theme? Could it form basis of study? Setting study: Does setting play a major role in advancing significance of work? Narrative technique study: Describe and discuss narrative structure. After all that: You should be able to narrow down topic to manageable size. i.e. a paper on Dante’s Inferno may be reduced to a study of Dante’s criticism of the corruption of the Church. On Gatsby, a paper on the corruption of the American Dream. The Working Bibliography A bibliography is a list of sources (books, journals, websites, periodicals, etc.) one has used for researching a topic. A bibliography includes the bibliographic information (i.e., the author, title, publisher, etc.). ASAP – begin compiling a working bibliography – a list of references that may provide information about your topic. Go to library. See indexes of reference books. Use the Internet (smartly) (more on use of internet later)… What to Look For What is suitable? Be aware that some sources will ultimately not be used. Some will be more helpful than others. The following kinds of sources are listed in order of descending importance; that is, the first one would probably yield the most information, while the last one would probably be least helpful: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A book or essay on primary source about topic or possibly related topic. A book or essay on author about your topic or a possibly related topic. A book or essay your author’s period about your topic or related. A general study of primary source. A general critical study of your author. A study of the life and works of your author (a critical biography). NOT SUITABLE: a biography of your author! The Annotated Biography An annotated bibliography includes a summary and/or evaluation of each of the sources. Depending on your project or the assignment, your annotations may do one or more of the following: 1. 2. 3. Summarize: Some annotations merely summarize the source. What are the main arguments? What is the point of this book or article? What topics are covered? If someone asked what this article/book is about, what would you say? Assess: After summarizing a source, it may be helpful to evaluate it. Is it a useful source? How does it compare with other sources in your bibliography? Is the information reliable? Reflect: Once you've summarized and assessed a source, you need to ask how it fits into your research. Was this source helpful to you? How does it help you shape your argument? How can you use this source in your research project? Your annotated bibliography may include some of these, all of these, or even others. Why should I write an annotated bibliography? To learn about your topic: Writing annotated bibliography is excellent preparation project. Just collecting sources for a bibliography is useful, but when you have to write annotations for each source, forced to read each source more carefully.You begin to read more critically instead of just collecting information. To help you formulate a thesis: Every good research paper is an argument. The purpose of research is to state and support a thesis. So a very important part of research is developing a thesis that is debatable, interesting, and current. Writing an annotated bibliography can help you gain a good perspective on what is being said about your topic. By reading and responding to a variety of sources on a topic, you'll start to see what the issues are, what people are arguing about, and you'll then be able to develop your own point of view. Format The annotations for each source are written in paragraph form. The lengths of the annotations can vary significantly from a couple of sentences to a couple of pages. The length will depend on the purpose. If you're just writing summaries of your sources, the annotations may not be very long. However, if you are writing an extensive analysis of each source, you'll need more space. You can focus your annotations for your own needs. A few sentences of general summary followed by several sentences of how you can fit the work into your larger paper or project can serve you well when you go to draft. The bibliographic information:The bibliographic information of the source (the title, author, publisher, date, etc.) is written in MLA. SAMPLE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ENTRIES This example uses the MLA format for the journal citation. NOTE: Standard MLA practice requires double spacing within citations. (This is wrong due to space constrictions). Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions onWriting and Life. New York: Anchor Books, 1995. Lamott's book offers honest advice on the nature of a writing life, complete with its insecurities and failures. Taking a humorous approach to the realities of being a writer, the chapters in Lamott's book are wry and anecdotal and offer advice on everything from plot development to jealousy, from perfectionism to struggling with one's own internal critic. In the process, Lamott includes writing exercises designed to be both productive and fun. Lamott offers sane advice for those struggling with the anxieties of writing, but her main project seems to be offering the reader a reality check regarding writing, publishing, and struggling with one's own imperfect humanity in the process. Rather than a practical handbook to producing and/or publishing, this text is indispensable because of its honest perspective, its down-to-earth humor, and its encouraging approach. Chapters in this text could easily be included in the curriculum for a writing class. Several of the chapters in Part 1 address the writing process and would serve to generate discussion on students' own drafting and revising processes. Some of the writing exercises would also be appropriate for generating classroom writing exercises. Students should find Lamott's style both engaging and enjoyable. Bernethy, Thomas P.The Burr Conspiracy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954. The first in a burst of books published on Burr since 1954. Abernethy incorporates previously unused primary sources in his attempts to prove that Burr did attempt to wrest Louisiana from the United States. Blackford, William W. WarYears with Jeb Stuart. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1946. A sympathetic and intelligent close-up of Stuart and the interesting young men around him. The author served as Chief Engineer on Stuart's staff and observed form his commander's side nearly all of the operations of the cavalry from June, 1986, to the end of January, 1964.