'Pro-Life': On the Morality of Abortion

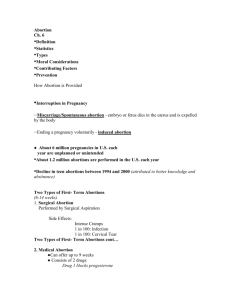

advertisement

Not ‘Pro-Choice’ & Not ‘Pro-Life’: On the Morality of Abortion (& related issues in famine aid and animals and ethics) Nathan Nobis www.NathanNobis.com www.WhyThinkThat.com aphilosopher@gmail.com Why did I pick the topic of abortion? “It sometimes appears that the quality of our thought on a topic is inversely proportional to the intensity of our emotions concerning that topic.” -- Fred Feldman, Confrontations With the Reaper: A Philosophical Study of the Nature and Value of Death (Oxford, 1994). Some common, low quality ‘arguments’ about abortion: A “pro-choicer” might say: A “pro-lifer” might say: “A woman has the right to choose to do “It’s always wrong to ‘play God.’ Abortion is ‘playing God.’ So abortion is wrong.” whatever she wants with her own body. Therefore, abortion is morally permissible.” These arguments are awful! Does a woman have ‘the right to choose to do whatever she wants with her own body?’ Obviously not! Simple, clear counterexamples show this. Is it wrong to ‘play God’? Depends on what you mean; suppose ‘playing God’ means ‘influencing the size of the future population.’ Again, this is obviously not wrong. We can do better. Philosophers – like you – can help improve how people reason. My goal: provide some basic ‘logical skills’ to help us better think about abortion and help us help others think more carefully about the topic. These skills are helpful in thinking about other ethical topics also. Three things to do to think more carefully about ethics: 1. Avoid ambiguity. 2. Words can have more than one meaning, so be clear on the exact meaning of what is being said. Ask, “What do you mean by that word (term, idea)?” (Why is this important?) Be precise. Is what is said true (or false) of some things, all things? (If not all, what are the exceptions?). “Existential” and “universal” quantifiers are often missing. (Why is this important?) Three things to do, from a logical point of view: Think in terms of arguments, i.e., sets of reasons given in defense of various conclusions. 3. Ask, “Why think that? What reasons are there? Often a missing, unstated premise or claim needs to be added to get from that answer – the offered reason – to the conclusion. You need to find that and see if there are any counterexamples to it, i.e., exceptions which show it to be false. Are these reasons good reasons? Suppose you asked, “So what do you think about abortion?” Some common responses: “I’m pro-choice. I think abortions are morally ok. It’s not wrong for a woman to have an abortion.” “I’m pro-life; I am against abortion. I think abortion is wrong. It is not morally ok for women to have abortions.” Logical point: recall ‘precision’ What are these people’s views, exactly? The quantifiers – all’s and some’s – were missing. All abortions? Some abortions? Most abortions? Few abortions? Abortions except in some special circumstances? (Which?) All possible abortions? Always morally wrong (or right)? Never morally OK (or wrong)? Wrong (or right) except in special circumstances? Couldn’t be wrong (or right)? A response to these common, imprecise views: No reason to assume – at the outset – that all abortions are morally equal or in the same moral category, i.e., that they all right or all wrong. Why’s this? Because abortions affect a range of beings. Differences in these beings might make a difference to the morality of how they should be treated. E.g., very early embryos & fetuses: “a fertilized egg, only thirty hours after conception. Magnified here, it is no larger than the head of a pin. Still rapidly dividing, the developing embryo, is called a zygote at this stage” 4- 5 weeks: “Embryo is the size of a raisin .. embryo's tiny heart has begun beating. The neural tube enlarges into three parts, soon to become a very complex brain. The placenta begins functioning. The spine and spinal cord grows faster than the rest of the body at this stage and give the appearance of a tail.” And far later fetuses: “24 weeks - Seen here at six months, the unborn child is covered with a fine, downy hair called lanugo. Its tender skin is protected by a waxy substance called vernix. Some of this substance may still be on the child's skin at birth at which time it will be quickly absorbed. The child practices breathing by inhaling amniotic fluid into developing lungs.” (Pictures from WESTSIDE CRISIS PREGNANCY CENTER: http://www.w-cpc.org/ I googled ‘fetal development’ to find it.) Any morally relevant differences among the range of fetuses? Standard “pro-choicer” seems to say ‘no,’ that any abortion affecting any fetus, at any stage, is morally permissible. No restrictions are morally justified. Standard “pro-lifer” seems to say ‘no’ too: any abortion affecting (almost?) any fetus, at any stage, is seriously morally wrong. Permitting (almost?) any abortions would be wrong. However, you might think that the issues are more subtle; you might think that (empirical, scientific) facts about fetuses (and women and girls, too) makes a difference to the morality of an abortion. (An aside: a poor objection from anti-‘extremist’ motivations. What’s wrong with those two positions – as they were just characterized – is that they are ‘extreme.’ More ‘moderate’ positions tend to be correct, when it comes to moral issues. Response: No, ‘extreme’ positions are sometimes right. You are an ‘extremist’ about many things: child abuse, rape, torture for fun, etc. You are against it all the time and you think any ‘moderates’ are mistaken.) Despite their differences, fetuses are human, so abortion is wrong! Are all fetuses ‘human’? What do you mean? Recall ‘precision’ & ‘meaning’: But, as a matter of logic, how to you get from that true premise to either of these conclusions?: All biologically human fetuses are biologically human, that’s for sure! Who would disagree?! All abortions are morally wrong, or even Some abortions are morally wrong. Need to add the missing premise(s)! Is the missing premise (2) true or not? 1. 2. 3. All biologically human fetuses are biologically human. [True] Anything that is biologically human is wrong to kill. (or, if X is biologically human, then it is wrong to kill X). Therefore, it is wrong to kill human fetuses. Actually, we need to make (2) more precise. Is it true now?: 1. 2. 3. All biologically human fetuses are biologically human. [True] Anything that is biologically human is always wrong to kill. (or, if X is biologically human, then it is always wrong to kill X). Therefore, it is always wrong to kill human fetuses. Schema for arguments that premise (2) is false: If it is true that ‘anything that is biologically human is always wrong to kill,’ then ___X___ is also true. 2. But ___X___ is not true. 3. Therefore, it is not true that it’s always wrong to kill anything that is biologically human. (modus tollens) What are good candidates for X? 1. Since (2) is false, this argument against abortion is not sound. If the premise was ‘if X is biologically human, then it’s sometimes wrong to kill X’ then we’d need more information to determine whether this was one of those cases. New argument: “Fetuses are alive. It’s always wrong to kill anything living, so it’s wrong to kill fetuses.” Any better? Maybe ‘human’ means something else, like ‘persons.’ People say, “Fetuses are ‘persons’ from the moment of conception.” 1. All fetuses are persons. 2. All (innocent) persons are always wrong to kill. [Are there exceptions, e.g. self-defense?] 3. Therefore, all fetuses are always wrong to kill, so abortion is wrong. Premise (2) is questionable. But are any or all fetuses ‘persons? Is there a way to rationally answer this question, i.e., decide what persons are? I think there is. I think there is a way to make progress in deciding what terms, words mean or what their correct definitions are. The methodology: make lists of things that are clearly an X, clearly not an X and things that we’re not clear about. We then develop a hypothesis that best explains the patterns in the list. Building a definition of a person & getting clear on the concept: Clearly a person Not Clear Either Way Clearly not a person Individuals like us here. • who else? • • Fetuses (or else we’re just assuming that they are, or are not, “persons”) • Some (or all?) non-human animals • what / who else? • Rocks • Old cars • Livers, hearts • cells, tissues • Tables, chairs • Plants • decomposed human corpses • what else? Does it make sense to say that the concept of “person” applies to these fictional beings? Were they to exist, would they be persons? If God(s), angels, &/or devils exist, are they persons? The (traditional, Western monotheistic) concept of God is an immaterial person who has some exceptional abilities and attributes, to say the least. Same w/ Eastern religions Might any of these beings be ‘persons’? Or are they more like non-persons? A rough, vague hypothesis: all beings with a personality, who are conscious, feeling, with beliefs, desires, memories, a sense of the future, ability to communicate, etc. are “persons.” If this is definition is true, then: Being biologically human is not logically necessary for personhood; it is not logically sufficient either. If God exists, there is a person without a physical body. So it appears that having a body is not conceptually necessary to being a person. Personhood is a consequence of one’s psychology or mental make-up. If this definition is false, then what are persons?! What other definition might work? Are any fetuses “persons,” on this characterization? Early to mid-term fetuses definitely are not. So the premise ‘All fetuses are persons’ is false. Note: don’t get troubled ! Don’t think that we’ve established this: if something is not a person, then there are never any moral constraints on how it can be treated. Conclusions on ‘personhood’ argument: All fetuses are persons. [False] 2. All (innocent) persons are always wrong to kill. [False] 3. Therefore, all (innocent) fetuses are always wrong to kill, so abortion is wrong. The premises are false, so unsound. 1. Reply: fetuses are ‘potential’ persons! Reply to reply: “True, some fetuses could and would become persons.” But, again, we’d get to the sought conclusion only if this were true: If something is a potential X, then X has the ‘moral rights’ of an actual X now. X = Parent? President? Tenured professor? Driver of a car? College graduate? Potentiality revisited: “There are ‘potential people’ “out there” in the future. Abortion prevents them from being brought into the world. It is wrong to prevent people from being brought into the world, so abortion is wrong.” But birth control, abstinence and not-doingwhat-you-can-to-reproduce-now do the same thing. Are those always wrong? Another idea: If someone would naturally develop into something if left alone, then it’s wrong to prevent that from happening. Conclusions on some common anti-abortion arguments: Arguments from the biological ‘humanity’ and ‘personhood’ of fetuses, as well as various (simple) arguments from potential all have false (sometimes unstated) premises. These arguments are all unsound. “Self defense” considerations might sometimes be relevant (if fetuses were persons). I’ve said little about this. However, perhaps that there are other, strong anti-abortion arguments. Ideas? Why ‘pro-life’ is misleading: the concern isn’t for all life, or even all conscious, sentient life. Indifference to human starvation and severe poverty: “The Singer Solution to World Poverty,” NY Times, September 5, 1999 Indifference to the deaths, and suffering, of billions of animals. A simple argument for ethical vegetarianism: 1. 2. 3. 4. It’s wrong to cause, and support, needless pain, suffering and death, especially when it is easy to do so. Buying dairy, meat and eggs supports causing needless pain, suffering and death. It is easy to not buy such products (and you & others can benefit from not doing so) Therefore, you should not purchase meat, dairy and eggs. Back to abortion: So should you be ‘pro-choice’? No, not as I’ve characterized it, in terms of the view that all (possible) abortions are morally permissible. Some abortions might have features that make them morally problematic, perhaps quite seriously. Most obvious feature: later fetuses can experience pain and suffer. Undeniably relevant. Peter Singer: “If a being is capable of suffering, there can be no justification for not taking that suffering into account.” Fetal Pain: The Scientific Evidence Conservative estimates are at 18 weeks, but the consensus in the medical literature is that the capacity for a fetus to feel pain arises at about 28-30 weeks. (David Benetar, “A Pain in the Fetus: Toward Ending Confusion About Fetal Pain,” Bioethics, 15, 1, 2001, 5576). When are most abortions? Fortunately, nearly all are well before the 18th week. (4th month!). CDC data. (See recent article by Ken Himma in Faith and Philosophy for references). However, some abortions are, or at least could be, later. Raise serious moral concern. “Pro-choicers” seem to want to deny this and ignore the facts about the possibility of fetal pain: ignoring something quite important. Mitigating concerns: Anesthesia. Concerns for the life (quality and quality) of the fetus or newborn. Concerns for the safety and well-being of the mother. However, some kind of truly unconditional “pro-choice” position seems indefensible. Is the “most actual abortions are morally OK, but a few later abortions might not be” position home free? Not so easy. The failure of these arguments against abortion does not simply establish the permissibility of abortion. True, if there’s no reason to think it’s wrong, then, of course, there’s no reason to think it’s wrong, but maybe there are such reasons… Harder principles to evaluate: Actions, including abortions (and not having abortions) affects the future. Which are permissible and which aren’t? Hard to tell, esp. in light of “opportunity costs.” If something is not a person, is not conscious, and cannot feel pain, then it is never wrong to kill or destroy it. Conclusions?? Much more to talk about!