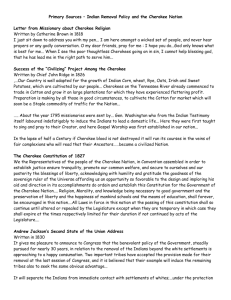

Andrew J and Indians 2

advertisement

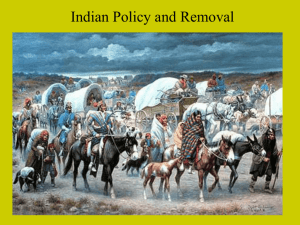

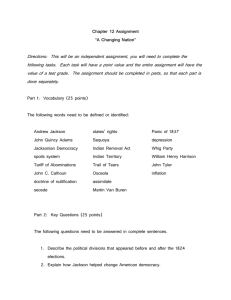

Andrew Jackson & the Indians. Was it Really Progress for America? Encompassing portions of seven southeastern United States, the Cherokee Nation of the early 1800’s contained some of the most fertile farm lands in the country1. Also within its boundaries were precious minerals such as gold and virgin forests. To a young nation still recovering from a war for independence, this area was eyed by those who wanted to grow a nation. The “people” who occupied this land were farmers, merchants, businessmen and even had their own written language and government, they were seen as an obstacle to growth and democracy by those in the US Government, and after years of poor land stewardship by the settlers, they petitioned the government to make available to them these jewels within the heathen nation. Their argument was that the savages were not Christian and more often rejected the teachings of the church and therefore were incapable of taking care of God’s creation, besides, did not the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few? It was said that in order for the nation to grow, become prosperous and ensure that its citizens were entitled to their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, all the “non-Americans” east of the Mississippi needed to be removed by any means possible. During the late 1820’s, the United States underwent one of its “growth spurts.” As immigration from Europe to America was steadily increasing and the western frontier had yet to be settled, the need for more land and resources grew almost as fast as the population. The 1 Trail of Tears; The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation, John Ehle president at time, Andrew Jackson, was engaged in the “reconstruction” of a nation that, a little over 30 years earlier, had experienced a war of independence and was involved in several minor skirmishes that had tested the toddler nations ability to stand on its own. For whatever reason, the population was reluctant to look to the west for new areas to settle, and therefore looked within its current borders for areas to farm and populate. In doing this the eyes of the nation fell upon the lands of the Native peoples of the southeast, primarily the Cherokees. As president, Jackson was viewed as a “common man,” one of the little folk standing up to the establishment so to speak, and doing the will of the people. So when the people began to speak to him concerning their need and desire to “expand” into these pristine farmlands, which were currently inhabited by heathens and savages, he listened. Acting in the “best interests” of the young nation, Jackson devised a plan to rid the land of the un-clean and open it up to his “people.” The Indians of the southeast had already left a bad taste in Jackson’s mouth, and both the Creek and Cherokee people seemed to be in his sights (even though the latter served the General well during the War of 1812). The Creek had been a nuisance from the beginning of the colonies, aligning themselves with the British in two wars and constantly attacking and harassing the frontier settlements. The seemingly “selfish and arrogant” Cherokees were sitting on both prime agricultural land and a possible mother lode of gold. These people became, in Jackson’s eyes were a roadblock to the growth and prosperity of the nation. Combined with the cries from his “people” and his duty to America, along with his reputation as a “common man,” Jackson had to make some difficult decisions on whether to compromise or remove the natives altogether. Andrew Jackson was known as a brilliant military leader and a renowned Indian fighter. He gained this reputation from chasing the British out of New Orleans and pacifying the natives of the Mississippi Valley. But known to only a few Jackson was also a compassionate combatant. In one instance where he led an attack on the Creek village at Talluschatches, a small Indian child was found still clutched in his dead mother’s arms. The child was brought to him, and among the cries of, “Kill the little Brown Skin Bastard,” Jackson promptly refused. Instead he took the child back to Hermitage and “adopted” him. Another incident was where Jackson refused to kill the last surviving warrior of a Creek War Party. The Indian stood alone in Jackson’s face and said, “I am not afraid of you. I fear no man, for I am a Creek warrior…. You may kill me if you wish.” Jackson held back his soldiers, who wanted to do just that, and let the warrior (Red Eagle) depart, claiming, “Any man who would kill as brave a man as this would rob the dead.” But apparently the later cries of the population overpowered what compassion Jackson once had towards the Natives2. During the late 1820’s, the president began to devise a plan to “relieve the Indians of the southeast of the burden of so much land and responsibility, and offer them a new world out in Oklahoma, where the white man has no interest.” In one of Jackson’s State of the Union messages, he stated that the “Indian Removal would be voluntary.”3 Whether he meant the Indians would “volunteer” to move or that the citizens would “volunteer” to move them was unclear. But whatever it meant a wave of both peaceful and violent coercion had already began in an attempt to get the Indians to willingly leave. With promises of cash, one homestead per family and pastures full of livestock out in Indian Country, the gentle persuasion began, but on a cold overcast day in December of 1835, the tactic that worked best was “swift deception. While a delegation of Cherokee leaders were in Washington, DC attempting to resolve the issue of removal, a small group of locals, “acting on behalf of the Federal Government,” 2 3 The Cherokee Indian Nation; A Troubled History, University of Tennessee Press Born Fighting, James Webb enticed about 50 Cherokees into a meeting hall in New Echota, Georgia, among them was Cherokee statesman John Ridge. All those in attendance were offered food and drink, and presented with the falsehood of a “promised land” across the big river to the west. Ironically this particular group had, in fact, been gathered by Ridge and went willingly to the meeting house. Ridge, who was once one of Chief John Ross’s “right hand men,” had split from the Principal Chief months earlier, and formed his own agenda (pro-removal). As expected the task of convincing Ridge’s group was not a difficult one, and on 28 December, 1835, the fate of the Cherokee nation was sealed through the blindness of a few. Although the actual removal of the Cherokees did not begin until 1838, Ridge and his family departed almost immediately for Indian Territory, but as fate would have it, on June 22, 1839, a group of “Late Comers” assassinated Ridge and his father, Elias Boudinot, for having signed the treaty4. For the most part, the Indian removal is commonly known as the “Trail of Tears.” This label however only applied to the Cherokee removal as other tribes had sorrowful descriptions of their own plight, but even as the darkest night has its dawn, such was the case during the postremoval period. Almost immediately following the vacating of Indian lands in the southeast, those who lived near this newly opened territory rushed in to lay claim to them. One “settler” moved straight into a fully furnished farmstead, complete with crops and livestock, while the previous Indian owners were literally being ushered into an Army wagon for the ride to the Deep Creek “holding area,” just outside of Bryson City, NC. As sad as this seemed this was the spark for one of the largest agricultural “revolutions” in the southeast5. Prime lands for growing cotton, sorghum, potatoes, rice, and several other crops were either plow ready or awaiting harvest. Large green pastures for livestock were also made available for the population; in addition, 4 5 The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears, Theda Perdue & Michael D Green Trail of Tears; The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation, John Ehle plentiful animals and implements were left behind by the Indians. Even the Carolina Gold Rush, as short lived as it was, helped provide a means for the federal government to pad its coffers (as they laid claim to 80% of the gold yielding lands for that sole reason). Overall there was an estimated 1.7 million square acres of “new land” available, almost two-thirds of which lie in North Georgia alone. Speaking in Tennessee in May of 1839, Andrew Jackson touted the new addition to the union as, “A reward from the Almighty for ridding the land of the heathenous savages.”6 Although the Indian Removal of the 1830’s wrought death, hell and destruction upon the native peoples of the southeast there was, through the eyes of most true Jacksonian Americans, a golden lining, and that was they had been led by a president who stood up for the common man, against both the savages and the establishment, to provide for his “people.” Today one can rightfully argue that the forced removal of the native peoples of the south was one of the darkest days in American history and that a compromise of peaceful coexistence should have been sought, but the same individual cannot deny that the benefits far outweighed the inconveniences faced by those removed, and as a result, the cold hard reality of American growth and prosperity would not be what it is today. After watching this dreadful event in her history, lady Liberty probably remarked, “As this wound heals, I will become stronger.” 6 James Mooney’s History, Myths and sacred Formulas of the Cherokees