linear momentum

advertisement

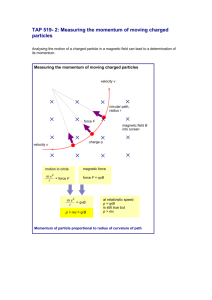

Consider the general curvilinear motion in space of a particle of mass m, where the particle is located by its position vector r measured from a fixed origin O. v The velocity of the particle is r is tangent to its path. The resultant force F of all forces on m isin the direction of its acceleration a v . We may write the basic equation of motion for the particle, as F ma mv or d d F mv mv G G dt dt Where the product of the mass and velocity is defined as the linear momentum G mv of the particle. This equation states that the resultant of all forces acting on a particle equals its time rate of change of linear momentum. In SI, the units of linear momentum mv are seen to be kg.m/s, which also equals N.s. Linear momentum equation is one of the most useful and important relationships in dynamics, and it is valid as long as mass m of the particle is not changing with time. We now write the three scalar components of linear momentum equation as Fx G x Fy G y Fz G z These equations may be applied independently of one another. The Linear Impulse-Momentum Principle All that we have done so far is to rewrite Newton’s second law in an alternative form in terms of momentum. But we may describe the effect of the resultant force on the linear momentum of the particle over a finite period of time simply by integrating the linear momentum equation with respect to time t. Multiplying the equation by dt gives we integrate from time t1 to time t2 to obtain dG F dt t2 Fdt t1 G2 G1 Fdt dG , which dG G2 G1 G linear impulse change in linear momentum Here the linear momentum at time t2 is G2=mv2 and the linear momentum at time t1 is G1=mv1. The product of force and time is defined as the linear impulse of the force, and this equation states that the total linear impulse on m equals the corresponding change in linear momentum of m. Alternatively, we may write G1 Fdt G2 I which says that the initial linear momentum of the body plus the linear impulse applied to it equals its final linear momentum. m G2 mv2 v1 G1 mv1 = + Fdt The impulse integral is a vector which, in general, we may involve changes in both magnitude and direction during the time interval. Under these F and G in component form conditions, it will be necessary to express and then combine the integrated components. The components become the scalar equations, which are independent of one another. t2 F dt mv x mv x 1 G x x 2 2 G x1 G x y2 G y1 G y t1 t2 F dt mv mv G y y 2 y 1 t1 t2 F dt mv z t1 mv z 1 Gz z 2 2 G z1 G z There are cases where a force acting on a particle changes with the time in a manner determined by experimental measurements or by other approximate means. In this case, a graphical or numerical integration must be performed. If, for example, a force acting on a particle in a given direction changes with t2 the time as indicated in the figure, the impulse, t1 to t2 is the shaded area under the curve. t1 F dt , of this force from Conservation of Linear Momentum If the resultant force on a particle is zero during an interval of time, its linear momentum G remains constant. In this case, the linear momentum of the particle is said to be conserved. Linear momentum may be conserved in one direction, such as x, but not necessarily in the y- or z- direction. G 0 G1 G2 mv1 mv2 This equation expresses the principle of conservation of linear momentum. PROBLEMS 1. The 200-kg lunar lander is descending onto the moon’s surface with a velocity of 6 m/s when its retro-engine is fired. If the engine produces a thrust T for 4 s which varies with the time as shown and then cuts off, calculate the velocity of the lander when t=5 s, assuming that it has not yet landed. Gravitational acceleration at the moon’s surface is 1.62 m/s2. SOLUTION m 200 kg , v1 6 m / s , g 1.62 m / s 2 , Fdt mv 2 mv1 v2 ? motion 1 mg (5) (800 ) 2 (800 )2 200 v2 6 2 1620 800 1600 200 v2 6 v2 6 3.9 v 2 2 .1 m / s mg t 5 s, + T PROBLEMS 2. The 9-kg block is moving to the right with a velocity of 0.6 m/s on a horizontal surface when a force P is applied to it at time t=0. Calculate the velocity v of the block when t=0.4 s. The kinetic coefficient of friction is mk=0.3. y SOLUTION motion x W=mg P F y 0 N N mg 0 N 9(9.81) 88 .3 N Ff=mkN F f m k N 0.3(88 .3) in x direction t Fdt mv mv 72 dt 36 dt 0 t1 0.2 0 2 1 t 2 0.4 t 2 0.4 t1 0.2 0 0.3(88 .3)dt 9(v2 0.6) 72 (0.2) 36 (0.2) 26 .49 (0.4) 9v2 5.4 v2 1.823 m / s PROBLEMS 3. A tennis player strikes the tennis ball with her racket while the ball is still rising. The ball speed before impact with the racket is v1=15 m/s and after impact its speed is v2=22 m/s, with directions as shown in the figure. If the 60-g ball is in contact with the racket for 0.05 s, determine the magnitude of the average force R exerted by the racket on the ball. Find the angle b made by R with the horizontal. SOLUTION v2 y v2 y in x direction t 0 Fx dt mv 2 x mv1 x 0.05 Rx t 0 0.06 22 cos 20 0.06 15 cos10 0.05 R x 2.127 20° 10° v 1x v1 y v1 F dt mv y 0 Ryt 0.05 0 2 y 0.05 R y 0.325 R 43 .02 N Rx mv1 y 0.05 0.06 (9.81)t 0 0.06 22 sin 20 0.06 15 sin 10 R R y 6.49 N tan b x W=mg R x 42 .53 N in y direction t v2 x Ry Rx b 8.68 Ry Ry b Rx R PROBLEMS 4. The 40-kg boy has taken a running jump from the upper surface and lands on his 5-kg skateboard with a velocity of 5 m/s in the plane of the figure as shown. If his impact with the skateboard has a time duration of 0.05 s, determine the final speed v along the horizontal surface and the total normal force N exerted by the surface on the skateboard wheels during the impact. PROBLEMS (mB+mS)g y x N Linear momentum is conserved in x-direction; mB vBx mS vSx mB mS v 40 5 cos 30 0 40 5 v in y direction m B v By mS v Sy 0.05 N m B v 3.85 m / s mS g dt 0 0 40 5 sin 30 0 N 0.05 45 9.810.05 0 N 2440 N or N 2.44 kN In addition to the equations of linear impulse and linear momentum, there exists a parallel set of equations for angular impulse and angular momentum. First, we define the term angular momentum. Figure shows a particle P of mass m moving along a curve in space. The particle is located by its position vector r respect to a convenient origin O of fixed coordinates x-y-z. y with The velocity of the particle is v r, and its linear momentum is G mv . The moment of the linear momentum vector mv about the origin O is defined as the angular momentum H O of P about O and is given by the cross-product relation for the moment of a vector H o r mv r G The angular momentum is a vector perpendicular to the plane A defined by and . The sense of v products. H O is clearly defined by the right-hand rule for cross r The scalar components of angular momentum may be obtained from the expansion i k j z m yv z zv y i mzv x xv z j m xv y yv x k Ho m x y vx vy so that H ox m yvz zv y H o r mv vz H oy mzv x xvz In SI units, angular momentum has the units kg.m2/s =N.m.s. H oz m xv y yvx If F represents the resultant of all forces acting on the particle P, the moment M o about the origin O is the vector cross product We now differentiate Mo r F r mv H o r mv with time, using the rule for the differentiation of a cross product and obtain d H o r mv rm v r m v dt a r mr 0 m Mo The term v mv is zero since the cross product of parallel vectors is zero. Substitution into the expression for moment about O gives M o Ho The scalar components of this equation is M ox H ox M oy H oy M oz H oz The Angular Impulse-Momentum Principle To obtain the effect of the moment on the angular momentum of the particle M o H o from time t1 to t2. over a finite period of time, we integrate t2 or M o dt t1 t2 M o dt H o 2 dH o H o 1 Ho 2 Ho 1 H o r2 mv2 r1 mv1 H o t1 change in angular momentum total angular impulse The total angular impulse on m about the fixed point O equals the corresponding change in angular momentum of m about O. Alternatively, we may write 2 t2 H o 1 M o dt H o t1 Plane-Motion Application Most of the applications can be analyzed as plane-motion problems where moments are taken about a single axis normal to the plane motion. In this case, the angular momentum may change magnitude and sense, but the direction of the vector remains unaltered. t2 M o dt H o 2 H o 1 t1 t2 Fr sindt mv d 2 2 t1 mv1d1 Conservation of Angular Momentum If the resultant moment about a fixed point O of all forces acting on a particle is zero during an interval of time, its angular momentum H O remains constant. In this case, the angular momentum of the particle is said to be conserved. Angular momentum may be conserved about one axis but not about another axis. H o 0 H O1 H O2 This equation expresses the principle of conservation of angular momentum. PROBLEMS 1. The assembly starts from rest and reaches an angular speed of 150 rev/min under the action of a 20 N force T applied to the string for t seconds. Determine t. Neglect friction and all masses except those of the four 3-kg spheres, which may be treated as particles. SOLUTION t2 t1 v M z dt H z2 H z1 2 20 0.1 t 4 3 0.4150 0.4 60 T r m r sphere link pulley vsphere t 15 .08 s v v v z PROBLEMS 2. A pendulum consists of two 3.2 kg concentrated masses positioned as shown on a light but rigid bar. The pendulum is swinging through the vertical position with a clockwise angular velocity w=6 rad/s when a 50-g bullet traveling with velocity v=300 m/s in the direction shown strikes the lower mass and becomes embedded in it. Calculate the angular velocity w which the pendulum has immediately after impact and find the maximum deflection of the pendulum. SOLUTION Angular momentum is conserved during impact; t 0 (2) M O dt H O2 H O1 0 , H O1 H O2 MO 0 r mv 1 r mv 2 (1) 0.050 300 0.4 cos 20 3.20.22 6 3.20.42 6 0.050 3.20.42 w 3.20.22 w w 2.77 rad / s (ccw) v1´ 1 2 v2´ O w´ v2 w 2 1 v1 SOLUTION v1´ 1 2 v2´ O w´ v2 w 2 1 v1 Energy considerations after impact; T1 Vg1 T2 Vg 2 (Datum at O) 1 0.05 3.20.4 2.77 2 1 3.20.2 2.77 2 3.20.29.81 3.2 0.05 0.49.81 2 2 0 3.20.29.81cos 3.2 0.05 0.49.81 cos 52 .1o