The single market and the four freedoms

advertisement

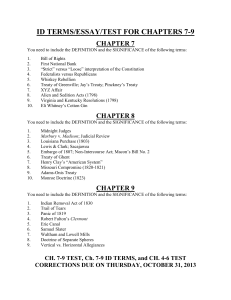

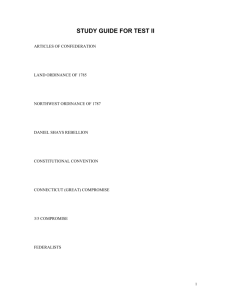

Business environment in the EU 1st Semester, Academic Year 2011/2012 Prepared by Dr. Endre Domonkos (PhD) I. The establishment of the single market I. The fundamental aim of establishing the European Economic Community was to create a common market for its Member States. The common market is an area where goods, services, capital and workers move freely without any restrictions. Following the Treaty of Maastricht, the principle of free movement was extended from workers to persons in general. Therefore the programme of the single market outlined in the Single European Act (SEA), signed on 18 February 1986. The legislative process related to the single market continues even today. I. The establishment of the single market II. As guaranteeing the single market and the four freedoms was the main aim of European integration, it is not surprising that Community legislation related to these areas provides the backbone of the acquis communautaire. Both the EC Treaty and secondary legal acts focus primarily on ensuring the efficient functioning of the single market. The four fundamental freedoms are guaranteed on the one hand by negative integration, and on the other hand by positive integration as well. There are several financial, technical, legal or administrative regulations rooted in the differences in taxation systems, standards, state or national traditions that prevent the European Community from fully realising the dream of the single market. II. The free movement of goods I. The free movement of goods (which is about free trade within the EU), is guaranteed by the creation of a customs union and the abolition of quantitative restrictions between Member States. The Member States abolished existing (and refrained from introducing new) customs duties and charges having equivalent effect levied on trade between each other. Discriminatory taxation is also prohibited in the EU. There are, however, three exceptions when charges having equivalent effect may be levied. II. The free movement of goods II. In addition to the abolition of customs duties and charges having equivalent effect, the setting up of a Common Customs Tariff (or Common External Tariff) forms another important element of the customs union. The Common Customs Tariff is the main instrument for regulating trade with third countries. Common customs tariffs are thus a precondition for guaranteeing the free movement of goods within Member States. In addition to setting common tariffs, the Member States have also harmonised their customs regulations and procedures, simplified border control formalities and developed forms of cooperation in the field of customs. II. The free movement of goods III. In order to guarantee the free movement of goods, in addition to the removal of customs duties, quantitative restrictions (trade and customs quotas) and measures with equivalent effect also had to be prohibited. For a long time, to define measures with equivalent effect was problematic. Originally, the Commission derived the ban on such measures from a 1970 Directive. Finally, in the Dassonville case of 1974, the European Court of Justice gave a uniform definition of the concept of measures with equivalent effect to quantitative restrictions, which was wider that the scope of the Directive. II. The free movement of goods IV. The ECJ set down a general formula defining the scope of the concept of measures with equivalent effect to quantitative restrictions: This has become known as the ‘Dassonville formula’. However, there is an exception to the ban on imposing restrictions on trade. Article 30 (ex article 36) of the EC Treaty stipulated that the prohibition of quantitative restrictions and measures with equivalent effect shall not preclude restrictions on grounds of: public morality, public policy or public security; the protection of health and life of humans, animals or plants; the protection of national treasures possessing artistic, historic or archaeological value or the protection of industrial and commercial property. II. The free movement of goods V. Another important ruling of the ECJ was in the so-called Cassis de Dijon case of 1979, which – together with the Dassonville-formula – was a milestone not only in the removal of trade barriers, but also in the entire process of the approximation of legislation. The Court ruled that a product which has been lawfully produced and marketed in one Member State should be able to circulate lawfully throughout the entire Community. (This is known as the principle of equivalence). The Cassis de Dijon judgment pointed out the concept of mutual recognition. II. The free movement of goods VI. The possible restrictions listed in the Cassis de Dijon judgment are generally referred to as mandatory requirements. Mandatory requirements set by the Court are not valid forever but only until Community legislation covers the relevant field. Member States can refer to mandatory requirements in cases when national measures apply without distinction to imported and domestically produced goods alike. This temporary nature of mandatory requirements is indicated by the Court’s subsequent decisions, which extended their scope. The Cassis de Dijon ruling put an end to the Member States’ practice of protecting their national products with various rules and standards. II. The free movement of goods VII. Mutual recognition practically became a new harmonisation mechanism in Community law, which was finally institutionalised by the Single European Act. Mutual recognition however does not mean that Member States have to adjust to the lowest national standards and requirements. The aim of the continuous exercise of extensive and thorough approximation of standards and technical specifications is to provide a solution to this problem. The enforcement of these rules is monitored by the Commission. Member States must always inform the Commission in advance if they wish to introduce new standards or regulations. III. The free movement of persons The universal right of free movement was no enshrined in the Treaty of Rome. The Treaty of Maastricht introduced the freedom of movement as a fundamental right that all EU citizens have, irrespective of whether they have economic activity. There are still different rules for various groups, depending on the economic nature of their activities , if any. Three different freedoms apply to people taking up residence in another Member State for the purposes of work. The free movement of these three groups is based on the same underlying principle: non-discrimination. III. The free movement of workers I. The freedom of movement for workers is fundamental pillar of European integration. Even today, a mere 2% of the EU’s active population works in another Member State. The free movement of workers can be hampered by three conditions: 1) discrimination between workers based on nationality; 2) legislation or administrative action that set different conditions for workers from different Member States; 3) the lack of coordination between social security systems. III. The free movement of workers II. According to Article 39, the key rights of workers of the Member States are the followings: The anti-discriminatory provisions of Article 39 also prohibit discrimination between workers from different Member States in terms of remuneration (including social and tax benefits), or any other conditions of work and employment. Under the secondary legislation of the Union, workers are entitled to bring with them their spouses and dependants (or children under the age of 21), even if they are not national of any Member State. However, the principle of the free movement of workers would not be very useful if workers lost their rights to social security benefits when moving from one Member State to another. For this reason, Article 42 of the EC Treaty stipulates that migrant workers can „carry over” the rights acquired. III. The free movement of workers III. The aim of the Treaty is clearly not to harmonise the social security systems of the Member States, but to create the necessary coordination between those systems. Council regulations are aimed at regulating the following areas: However, there are exemptions from the free movement of workers, whereby the Treaty allows for certain restrictions against foreign workers (from another Member State). According to Article 39 of the EC Treaty, such restrictions must be justified on grounds of public policy, public security or public health. Such limitations can only be an exception to the rule and have to be properly justified. IV. The freedom of establishment I. Self-employed persons form a separate category based on Community law. This category includes those working in the so-called liberal professions as well as different activities many of whom provide services. These people are entitled to freedom of establishment. Qualifications may vary greatly from one Member State to another in terms of their content and length, which makes it more difficult for citizens of other Member States to obtain a licence for the pursuit of professional activities. In the beginning, Member States tried to harmonise certain professions. IV. The freedom of establishment II. The mutual recognition of diplomas, degrees and certificates thus became a fundamental principle (both for people in a self-employed or employed capacity). In the case of the majority of professions, Member States mutually recognise diplomas issued by the others. Nonetheless, in certain professional fields (for example, law), the recognition of a person’s qualifications has to be requested from the local authorities. The significance of the freedom of establishment is that it covers both natural persons and legal entities. For the latter, it means the right of so-called „secondary establishment”. IV. The freedom of establishment III. The European Company Statute is a legal instrument that gives companies the option of forming a European Company – known formally by its Latin name Societas Europeae” (SE) – in one of four ways: In practice, this means that European Companies are able to operate throughout the EU on the basis of a single set of rules and a unified management and reporting system. There are exemptions from the freedom of establishment principle. Member States may impose certain restrictions on the grounds of public policy, public security or public health, as long as they are justified and proportionate to the objectives they are supposed to serve. V. The free movement of non-economically active persons I. With the Treaty of Maastricht, the freedom of movement became a fundamental right of every citizen of every Member State of the European Union. This is due to the fact that the Maastricht Treaty created the institution of Union citizenship and made the right to free movement a fundamental element of such citizenship. Citizenship of the Union means four specific rights. There are no restrictions whatsoever on EU citizens on short-term visits (travelling). All citizens of the Union are free to travel to and stay in another Member State for a period of three months. V. The free movement of non-economically active persons II. All limitations on goods purchased by travellers were also removed under the principle of free movement of goods and persons. Taxes on the products (VAT, excise duties) have to be paid at the point of purchase. Free movement involves not only the right to travel freely, but also the right to stay in any Member State for a sustained period, which includes the freedom to work, study, reside and stay in all Member States. This also means that citizens of the EU are free to choose their domicile in the area of the Union. However, if they intend to stay in a Member State for a period longer than three months, they need a residence permit. V. The free movement of non-economically active persons III. While for wage-earners, the conditions of free movement were already guaranteed by the Treaty of Rome and subsequent secondary legislation, for residence for other purposes the Council adopted three Directives on 28 June 1990, which regulate the general framework rules on the right of residence for non-economically active persons, the conditions governing the right of residence of people who have ceased their occupational activity (pensioners) and the conditions applicable to persons staying in another Member State for educational purposes (students). The main aim of the Directives is to regulate the conditions upon which citizens of another Member State may be entitled to a residence permit. V. The free movement of non-economically active persons IV. Free movement and travel to other Member States is facilitated by the fact that there are practically no border controls inside the EU. By integrating the Schengen Agreement and subsequent Schengen legislation (the so-called Schengen acquis) into the European Union and the acquis communautaire, the Amsterdam Treaty largely removed controls on passenger traffic on borders within the Union, except for the United Kingdom and Ireland. Persons crossing from one Member State to another can do so freely, while those who have entered from a third country can move on freely without any controls to other Member States. Moreover, citizens of the Union can cross the border with their identity cards (rather than passports). VI. The freedom to provide services I. The acquis (Article 50 of the EC Treaty) defines services as activities provided for remuneration, insofar as they are not governed by the provisions relating to the freedom on movement of goods, capital and persons. For the sake of clarity, the freedom to provide services applies to those services which have cross-border element, i.e. when the provider and the recipient of the service reside in different Member States. This does not mean that the service provider cannot temporarily pursue his activity in the state where the service is provided, and in fact he may even open a permanent representation there, but his activity must be fundamentally related to another Member State. VI. The freedom to provide services II. For the freedom to provide services the emphasis falls on the temporary (non-permanent) and cross-border nature of such activities. It is also important to note that the service is provided for remuneration, since – to a certain extent – the essence of the freedom to provide services is to embrace all those activities which are exercised for remuneration but which do not fall within the scope of the other three freedoms. The acquis stipulates that the remuneration must come from a private source, thus educational services paid by the state do not fall within scope of the free movement of services. In order to clarify the nature of services, Article 50 of the EC Treaty lists activities that – upon the fulfillment of the above conditions – are typically considered as services: VII. The prohibition of discrimination, the question of educational qualifications and the exceptions to the freedom to provide services I. The prohibition on discrimination also applies to the free movement of services. This means that Member States may not impose different conditions on service providers who exercise their activities from another Member State or on recipients of services in another Member State. It is important to note here that recipients of services cannot be restricted or discriminated against, which means that they have the right to travel to another Member State to buy services. This is a standard practice for a number of services. VII. The prohibition of discrimination, the question of educational qualifications and the exceptions to the freedom to provide services II. With its rulings, the Court has also extended the Dassonville formula, first applied to goods only, to services as well. The Directives on the mutual recognition of qualifications and the harmonisation of educational and training conditions also apply to the freedom to provide services. Certain activities are exempt from the provisions on the freedom to provide services, as in the case of the freedom of establishment and the free movement of goods. VIII. The liberalisation of the free movement of services I. Community law guarantees the freedom to provide services and the abolition of provisions restricting the movement of various services through means of directives. Finally, parallel to the programme of the single market, the liberalisation of intra-Community services gained new momentum in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Consequently, most services (e.g. banking, financial, air transport and telecommunications services) had been liberalised by the turn of the millennium, but in few areas, particularly where state-owned service providers were involved (e.g. electricity and gas), only the initial steps had been taken. VIII. The liberalisation of the free movement of services II. In the light of these developments, the Lisbon summit in March 2000 placed the so-called Internal Market Strategy for Services at the Centre of the Community’s new long-term economic policy. This new approach was needed because the traditional method of harmonisation and liberalisation, aimed at individual sectors, was no longer sufficiently effective. The reasons for introducing a new approach in the field of services were the followings: The new Internal Market Strategy for Services thus strives to create a comprehensive horizontal regulatory framework applicable in all sectors and flexible enough to ensure that services based on new technologies can develop for the benefit of the single market. VIII. The liberalisation of the free movement of services III. The new strategy consists of three elements: With the latter, the strategy aims at establishing horizontal rules covering services in all sectors, focusing particularly on the following six areas: The Draft Directive on services in the internal market (in short, the draft Services Directive and also known as the draft Bolkenstein Directive, so called the former European Commissioner who introduced it), which the Commission presented in January 2004, is aimed at establishing a truly single internal market in services by dismantling any remaining unjustified and discriminatory administrative obstacles to cross-border service provision. III. The liberalisation of the free movement of services IV. In essence, the Draft Directive introduced the principle of „country of origin” to cross-border services. The Draft Directive was severely criticised by the Member States with higher labour costs in the services sector, who were afraid of job losses caused by competition from (mainly new) Member States with cheaper labour. The other common fear was that the Draft Directive could have jeopardised the quality of services, by giving Member States with the lowest regulatory standards a competitive advantage. The Commission’s main aim is to make better use of the growth and jobcreation opportunities offered by the single market. IX. The free movement of capital I. Article 56 of the EC Treaty prohibits all restrictions on the movement of capital, both between Member States and between Member States and third countries. The EC Treaty includes provisions not only on the free movement of capital, but on the free movement of capital and payments as well. This distinction between capital and payments no longer made sense following the general liberalisation necessitated by the economic and monetary union; thus, nowadays, we only talk about free movement of capital. According to ex Article 67 of the Treaty of Rome, the free movement of capital and payments only had to be guaranteed to the extent required by the „proper functioning of the common market”. IX. The free movement of capital II. For a long time, the acquis mainly dealt with the free movement of capital connected with such cross-border activities. The decisive moment came with the adoption of a Directive in 1988, which liberalised capital transfers by abolishing all restrictions on movements of capital. The realisation of an unrestricted, free movement of all elements of capital was reinforced by the Maastricht Treaty, which set the free movement of capital as a precondition for joining the economic and monetary union. Thus, by the beginning of the second phase of the EMU on 1 January 1994, all payments and capital movements had been fully liberalised. X. Exceptions to the free movement of capital There are general exceptions to the free movement of capital. In addition, just as in the case of the free movement of goods, persons and services, the free movement of capital may be restricted on grounds of public policy or public security. The principle of a restriction being in proportion to the objective to be achieved applies here as well, which means that such restrictions are not permissible if the objective could be achieved by less restrictive means. This principle is strictly enforced by the European Court of Justice. XI. The single market and taxation I. In order to ensure the four fundamental freedoms, certain rules on taxation are necessary, pursuant to Articles 90 to 93 of the EC Treaty. It must, however, be made clear that the aim is not to harmonise taxes or create a single system of taxation. It should also be emphasized that the Treaty makes a clear distinction between rules on indirect and direct taxation. Article 93 of the EC Treaty empowers the Council to adopt provisions for the harmonisation of legislation concerning turnover taxes, excise duties and other forms of indirect taxation, to the extent necessary to ensure the establishment and the functioning of the internal market. Article 93 has helped to create very detailed common rules on valueadded tax and excise duties. XI. The single market and taxation II. Value-added tax (VAT) was first introduced in the Community in 1970. The creation of the single market in 1992 brought about the elimination of ‘tax borders’, which necessitated even closer harmonisation of VAT rates. The significant differences in VAT rates hindered the free movement of goods and services. According to a Directive adopted in 1992 on harmonising tax rates, the Member States have to apply a standard rate of VAT of a minimum 15%, with one or two reduced rates of no less than 5% applied for certain goods and services, serving primarily cultural and social purposes. The EU’s long term objective is to establish an origin-based Community VAT system. XI. The single market and taxation III. Since the introduction of the single market on 1 January 1993, excise duties have been payable at the place of consumption. Excise duties on alcoholic beverages, tobacco products and mineral oils are payable in the Member State of final consumption. Minimum rates of excise duties are also set at Community level. The only condition concerning direct taxes is that national tax systems must respect the four fundamental freedoms. As a practical consequence, Community legislation adopted in this area is aimed at avoiding double taxation and facilitating cross-border business activities. XI. The single market and taxation IV. Tax harmonisation is clearly one of the most sensitive issues of closer integration. Several Member States are understandably reluctant to pool their national sovereignty, as tax policy is the key fiscal instrument and a major component of each government’s political programme. As a result, unanimity has been maintained in the area of tax harmonisation. Replacing unanimity is so unrealistic that even the Treaty of Lisbon did not attempt to extend qualified majority voting to taxation; thus the Member States preserved their right of veto. XII. Provisions of the Treaty of Lisbon in relation with the single market I. According to the provisions of the Treaty of Lisbon the following changes should be highlighted: For the free movement of goods: For the free movement or persons: In the field of social security of migrant workers: For the freedom to provide services: XII. Provisions of the Treaty of Lisbon in relation with the single market II. Provisions for free movement of capital: Provisions for taxation: For taxation, the Treaty of Lisbon took on board all the provisions of the EC Treaty with one amendment, which enabled the Union to establish measures for the harmonisation of legislation, concerning taxation, provided that such harmonisation is necessary to ensure the establishment and functioning of the internal market and to avoid a distortion of competition.