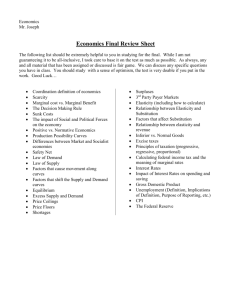

Document

advertisement

Working with Demand and Supply Price Ceilings • Government-imposed maximum price that prevents the price of a good from rising above a certain level in a market • Short side of the Market prevails • Price ceiling creates a shortage – While the price decreases, the opportunity cost may rise • Black Market – A market created by unintended consequences of government intervention • Goods are sold illegally at a price above the legal ceiling Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 1 Figure 1: A Price Ceiling in the Market for Maple Syrup 5. With a black market, the lower quantity sells for a higher price than initially. Price per Bottle 3. and decreases quantity supplied. 4. The result is a shortage – the distance between S R and V. T $4.00 3.00 R 2.00 E V 2. increases quantity demanded D 40,000 50,000 60,000 1. A price ceiling lower than the equilibrium price . . . Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Number of Bottles of Maple Syrup per Period 2 Price Floors • Government imposed minimum amount below which price is not permitted to fall – Price floors for agricultural goods are commonly called price support programs • When sellers produce more of the good than buyers want at the price floor – Remaining goods become a surplus that no one wants at the imposed price • Government responds by maintaining price floors – Uses taxpayer dollars to buy up entire excess supply of the good in question – Prevents excess supply from doing what it would ordinarily do • Drive price down to its equilibrium value Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 3 Figure 2: A Price Floor in the Market for Nonfat Dry Milk Price per Pound 2. decreases quantity demanded . . . 1. A price floor higher than the equilibrium price . . . 3. and increases quantity supplied. S J K $0.81 A 0.65 4. The result is a surplus the – distance between K and J – which government must buy. D 180 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 200 220 Millions of Pounds 4 Limiting Surplus • A price floor creates a surplus of goods – In order to maintain price floor, government must prevent surplus from driving down market price • Government often accomplishes this goal by purchasing surplus with taxpayers dollars • Price floors often get government deeply involved in production decisions – Rather than leaving them to the market Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 5 Supplier’s perspective • A producer considers increasing his price • Is it a good idea? • Higher price means more revenue per unit output BUT… • Lower units of quantity sold (downward sloping demand). Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 6 The Demand Schedule Demand for Maple Syrup Price (per bottle) $1.00 Quantity Demanded (bottles per month) 75,000 $2.00 60,000 $3.00 50,000 $4.00 35,000 $5.00 20,000 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 7 The Demand Schedule Demand for Maple Syrup Price (per bottle) Revenue (price times quantity) $1.00 Quantity Demanded (bottles per month) 75,000 $2.00 60,000 $12,000 $3.00 50,000 $150,000 $4.00 35,000 $140,000 $5.00 20,000 $100,000 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles $75,000 8 The Problem with Rate Change • Rate of change of quantity demanded compared to the change in price is not a good measure of price sensitivity – Doesn’t tell whether a change in price or a change in quantity demanded is a relatively large or relatively small change • Relative means compared to value of price or quantity before change Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 9 The Elasticity Approach • Elasticity approach improves on the problems with rate of change – By comparing percentage change in quantity demanded with percentage change in price • Price elasticity of demand (ED) for a good is percentage change in quantity demanded divided by percentage change in price %Q ED D %P • – Will virtually always be a negative number – Tells us percentage change in quantity demanded for each 1% increase in price Price elasticity of demand tells us percentage change in quantity demanded caused by a 1% rise in price as we move along a demand curve from one point to another Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 10 Calculating Price Elasticity of Demand • When calculating elasticity base value for percentage changes in price or quantity is always midway between initial value and new value – When price changes from any value P0 to any other value P1, we define the percentage change in price as % Change in Price ( P1 P 0 ) ( P1 P 0 ) 2 – When quantity demanded changes from Q0 to Q1, percentage change is calculated as % Change in Quantity Demanded Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles (Q1 _ Q0 ) Q Q 0 1 2 11 Figure 3: Calculating Price Elasticity of Demand Price per Laptop D $3,500 C 3,000 2,500 2,000 B 1,500 A 1,000 D 100,000 200,000 300,000 400,000 500,000 600,000 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Quantity of Laptops 12 An Example: Calculating Price Elasticity of Demand • Now let’s calculate an elasticity of demand for laptop computers using data in Figure 3 from point A to point B (500,000 600,000) 100,000 % Change in Quantity Demanded % Change in Price (500,000 600,000) 2 550,000 0.182, or 18.2 percent ($1,500 $1,000) $500 0.400, or 40.0 percent ($1,500 $1,000) $1,250 2 • Use percentage changes for price and quantity to calculate price elasticity of demand (ED) ED 0.182 0.46 0.400 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 13 Elasticity and Straight-Line Demand Curves • As we move upward and leftward along a straight-line demand curve – Same absolute increment in price will correspond to smaller and smaller percentage increments in price • Why? • As we move upward and leftward along a straight-line demand curve – Same absolute decrease in quantity corresponds to larger and larger percentage decreases in quantity • As we move upward and leftward by equal distances, percentage change in quantity rises – Percentage change in price falls • Elasticity of demand varies along a straight-line demand curve – Demand becomes more elastic as we move upward and leftward Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 14 Figure 4: Elasticity and StraightLine Demand Curves Since equal dollar increases (vertical arrows) are smaller and smaller percentage increases . . . Price 3 2 and since equal quantity decreases (horizontal arrows) are larger and larger percentage decreases . . . 1 demand becomes more and more elastic as we move leftward and upward along a straight-line demand curve. D Quantity Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 15 Categorizing Goods by Elasticity • Inelastic Demand – Price elasticity of demand between 0 and -1 Inelastic Demand % Change in Quantity Demanded 1.0 % Change in Price |% Change in Quantity Demanded| < |% Change in Price| • Perfectly Inelastic Demand – Price elasticity of demand equal to 0 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 16 Categorizing Goods by Elasticity • Elastic Demand – Price elasticity of demand with absolute value > 1 Elastic Demand % Change in Quantity Demanded 1 % Change in Price |% Change in Quantity Demanded| > |% Change in Price| • Perfectly (infinitely) Elastic Demand – Price elasticity of demand approaching minus infinity • Unitary Elastic Demand – Price elasticity of demand equal to -1 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 17 Figure 5: Extreme Cases of Demand (a) Price per Unit (b) Price per Unit D $4 $4 3 Perfectly Inelastic Demand 2 1 3 Perfectly Elastic Demand 2 D 1 20 40 60 80 100 Quantity Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 20 40 60 80 100 Quantity 18 Elasticity and Total Revenue • Total revenue (TR) of all firms in the market is defined as • TR = P x Q • When two numbers are both changing, percentage change in their product is (approximately) the sum of their individual percentage changes – Applying this to total revenue • % Change in TR = % Change in Price + % Change in Quantity Demanded • Assume demand is unitary elastic and Q rises by 10% – % Change in TR = 10% + (-10%) = 0 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 19 Elasticity and Total Revenue • If demand is inelastic, a 10% rise in price will cause quantity demanded to fall by less than 10% – % change in TR = 10% + (something less negative than –10%) > 0 • If demand is elastic, so that Q falls by more than 10% – TR will fall • % Change in TR = 10% + (something more negative than -10%) < 0 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 20 Elasticity and Total Revenue • Where demand is inelastic, total revenue moves in same direction as price • Where demand is elastic, total revenue moves in opposite direction from price • Where demand is unitary elastic, total revenue remains the same as price changes • At any point on a demand curve sellers’ total revenue (buyers’ total expenditure) is the area of a rectangle – Width equal to quantity demanded – Height equal to price Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 21 Figure 6: Elasticity and Total Expenditure Price per Laptop 2. At point B, revenue is $750 million. $3,500 3,000 2,500 2,000 1. At point A , where price is $1,000 and 600,000 laptops are demanded, revenue is $600 million. 3. Moving from A to B, expenditure increases, so demand must be inelastic over that range. B 1,500 A 1,000 D 500 100,000 200,000 300,000 400,000 500,000 600,000 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Quantity of Laptops 22 Availability of Substitutes • Demand is more elastic – If close substitutes are easy to find and buyers can cut back on purchases of the good in question • Demand is less elastic – If close substitutes are difficult to find and buyers can not cut back on purchases of the good in question Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 23 Narrowness of Market • More narrowly we define a good, easier it is to find substitutes – More elastic is demand for the good • More broadly we define a good – Harder it is to find substitutes and the less elastic is demand for the good • Different things are assumed constant when we use a narrow definition compared with a broader definition Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 24 Necessities vs. Luxuries • The more “necessary” we regard an item, the harder it is to find a substitute – Expect it to be less price elastic • The less “necessary” (luxurious) we regard an item, the easier it is to find a substitute – Expect it to be more price elastic Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 25 Time Horizon • Short-run elasticity – Measured a short time after a price change • Long-run elasticity – Measured a year or more after a price change • Usually easier to find substitutes for an item in the long run than in the short run – Therefore, demand tends to be more elastic in the long run than in the short run Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 26 Importance in the Buyer’s Budget • The more of their total budgets that households spend on an item – The more elastic is demand for that item • The less of their total budgets that households spend on an item – The less elastic is demand for that item Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 27 Using Price Elasticity of Demand: The War on Drugs • Every year U.S. Government spends about $20 billion on efforts to restrict the supply of drugs • Figure 9(a) – Market for heroin without government intervention • Figure 9(b) – Result of government efforts to restrict supply (current policy) • Figure 9(c) – Results of an effective policy of reducing demand Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 28 Figure 7a: The War on Drugs (a) Price per Unit S1 A P1 D1 Q1 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Quantity 29 Figure 7b: The War on Drugs (b) Price per Unit S2 B S1 P2 A P1 D1 Q2 Q1 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Quantity 30 Figure 7c: The War on Drugs (c) Price per Unit S1 A P1 P3 C D1 D2 Q3 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Q1 Quantity 31 Using Price Elasticity of Demand: Mass Transit • Elasticity studies show that long-run demand for mass transit is inelastic – Therefore, a rise in fare would increase revenues • However, most cities do not raise transit fares due to – Desire to provide low-income households with affordable transportation – Desire to manage traffic congestion – Desire to limit air pollution in the city • An increase in fares would increase revenue – Would also decrease ridership and require the city to sacrifice these other goals Hall & Leiberman; 32 Economics: Principles Using Price Elasticity of Demand: An Oil Crisis • • For the past five decades, Middle East has been a geopolitical hot spot Both military and economic government agencies ask “What if” questions – If an event in the Middle East were to disrupt oil supplies, what would happen to the price of oil on world markets? • Flipping the elasticity equation like so 1 E D % Change in Price % Change in Quantity Demanded • Tells us percentage rise in price that would bring about a 1 percent decrease in quantity demanded – Enables us to make reasonable forecasts about the impact of various events on oil prices • Once we have established our forecasted oil prices we can then use that data to examine effect that higher oil prices would have on many broader issues – Effect on U.S. inflation rate – Effect on number of flights offered by U.S. airlines Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 33 Income Elasticity of Demand • Percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in income – With all other influences on demand—including the price of the good—remaining constant EY % change in Quantity Demanded % Change in Income • Interpret this number as percentage increase in quantity demanded for each 1% rise in income Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 34 Income Elasticity of Demand • Income elasticities vs. price elasticities of demand – Price elasticity of demand • Measures effect of change in price of good – Assumes that other influences on demand, including income, remain unchanged – Income elasticity • Measures effect on demand we would observe if income changed and all other influences on demand—including price of the good—remained the same • Instead of letting price vary and holding income constant, now we are letting income vary and holding price constant Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 35 Income Elasticity of Demand • Another difference between price and income elasticity of demand – Price elasticity measures sensitivity of demand to price as we move along a demand curve from one point to another – Income elasticity tells us relative shift in demand curve—increase in quantity demanded at a given price • While a price elasticity is virtually always negative – Income elasticity can be positive or negative Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 36 Income Elasticity of Demand • Economic necessity – Good with an income elasticity of demand between 0 and 1 • Economic luxury – Good with an income elasticity of demand greater than 1 • An implication follows from these definitions – As income rises, proportion of income spent on economic necessities will fall • While proportion of income spent on economic luxuries will rise • But, it is important to remember that economic necessities and luxuries are categorized by actual consumer behavior – Not by our judgment of a good’s importance to human survival Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 37 Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand • Cross-price elasticity of demand – Percentage change in quantity demanded of one good caused by a 1% change in price of another good • While all other influences on demand remain unchanged EXZ % Change in Quantity of X Demanded % Change in Price of Z • While the sign of the cross-price elasticity helps us distinguish substitutes and complements among related goods • Its size tells us how closely the two goods are related – A large absolute value for EXZ suggests that the two goods are close substitutes or complements – While a small value suggests a weaker relationship Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 38 Price Elasticity of Supply • Percentage change in quantity of a good supplied that is caused by a 1% change in the price of the good – With all other influences on supply held constant ES % Change in Quantity Supplied % Change in Price Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 39 Price Elasticity of Supply • When do we expect supply to be price elastic, and when do we expect it to be price inelastic? – Ease with which suppliers can find profitable activities that are alternatives to producing the good in question • Supply will tend to be more elastic when suppliers can switch to producing alternate goods more easily – When can we expect suppliers to have easy alternatives? Depends on » Nature of the good itself » Narrowness of the market definition—especially geographic narrowness » Time horizon—longer we wait after a price change, greater the supply response to a price change Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 40 Price Elasticity of Supply • Extreme cases of supply elasticity – Perfectly inelastic supply curve is a vertical line • Many markets display almost completely inelastic supply curves over very short periods of time – Perfectly elastic supply curve is a horizontal line Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 41 Figure 8: Extreme Cases of Supply (a) (b) Price per Unit Price per Unit S Perfectly Inelastic Supply P2 Perfectly Elastic Supply S P1 Quantity per Period Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Quantity per Period 42 The Tax on Airline Travel: Taxes and Market Equilibrium • A tax on a particular good or service is called an excise tax – Shifts market supply curve upward by amount of tax • For each quantity supplied, the new, higher curve tells us firms’ gross price, and the original, lower curve tells us the net price • Who really pays excise taxes? – Buyers and sellers share in the payment of an excise tax • Called tax shifting – Process that causes some of tax collected from one side of market (sellers) to be paid by other side of market (buyers) Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 43 Figure 9a: The Tax on Airline Travel Price per Ticket (a) 4. and then find the minimum price needed for the market to supply that quantity. SBefore Tax $300 $260 1. One way to use the supply curve is to start with the price . . . Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 3. But another way is to start with a quantity . . . A 7 10 Millions of Tickets per Year 2. and then find the quantity supplied at that price. 44 Figure 9b: The Tax on Airline Travel Price per Ticket (b) SAfter Tax $360 A' SBefore Tax $300 A 3. But another way is to start with a quantity . . . 10 Millions of Tickets per Year 4. and then find the minimum price needed for the market to supply that quantity. Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 45 Figure 10: Effect of Excise Tax on Airlines 2. The $60 tax shifts the supply curve up by $60. Price per Ticket SAfter Tax B $340 3. In the new equilibrium, buyers pay $340. SBefore Tax $300 A 1. Before the tax, the supply curve is SBefore Tax and the price is $300. $280 4. And, net of the tax, sellers receive $280. Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles D Millions of Tickets per Year 46 Tax Incidence and Demand Elasticity • In most cases excise tax will be shared by both buyer and seller – For a given supply curve, the more elastic is demand, the more of an excise tax is paid by sellers – The more inelastic is demand, the more of the tax is paid by buyers Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 47 Figure 11: Tax Incidence and Demand Elasticity (a) Price per Ticket D (b) Price per SAfter Tax Ticket SAfter Tax SBefore Tax SBefore Tax B $360 $300 A 10 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles $300 Millions of Tickets per Year B A 2 10 D Millions of Tickets per Year 48 Tax Incidence and Supply Elasticity • Although there are extreme cases of supply elasticity, in general the following is true – For a given demand curve, the more elastic is supply, the more of an excise tax is paid by buyers – The more inelastic is supply, the more of the tax is paid by sellers Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 49 Figure 12: Tax Incidence and Supply Elasticity (a) Price per Ticket (b) SBefore and After Tax Price per Ticket $360 $300 A $240 SAfter Tax A $300 D 10 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles B Millions of Tickets per Year SBefore Tax D 8 10 Millions of Tickets per Year 50 The Market For Food • Shrinking and unstable incomes are problems for farmers • The market for farm goods would reach an equilibrium if it were allowed to do so • But farming seems to be special – Notion of small family farm has tremendous political appeal – Farmers have banded together to form powerful and effective government lobbies • Result has been continual government interference with supply and demand in agricultural markets around the world Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles 51 Figure 13: The Market For Food (a) (b) per SOld Technology Price Unit of Price per Unit of Food Food A SNew Technology P1 P2 SBad Weather A SGood Weather P1 B B P2 D Q1 Q2 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles D Quantity of Food Q1 Q2 Quantity of Food 52 Health Insurance and the Market for Health Care • Health insurance has definite benefits to our society • Our current health care system keeps patients from facing the full opportunity cost of their health care decisions – Can cause people to over consume health care • Health insurance reduces buyers’ incentives to monitor their health care expenditures closely or to shop around for Hall high-quality & Leiberman; 53 low-cost care Economics: Principles Figure 14: The Market For Health Care With Coinsurance Price per D After Insurance Examination $100 S DBefore Insurance B 70 50 A 100,000 150,000 Hall & Leiberman; Economics: Principles Examinations per Year 54