They Say I Say Summary and Graphic

advertisement

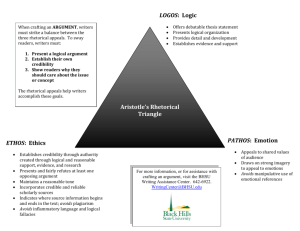

PART 1: BEGIN WITH WHAT ‘THEY SAY’ According to Graff and Birkenstein it is important to begin an argumentative essay with what others think and say about the issue at hand, or as they put it you start with what ‘They Say’. When you begin your writing with ‘They say’ you are entering the conversation that other writers and thinkers have begun before. Writers often forget that writing is a conversation with often unseen readers. Because writing differs from a regular conversation, readers are unable to ask questions of writers and must rely on the writer to provide enough information to answer any questions, especially the question, “Why are you telling me this?” The ‘They Say’ component addresses this question and alerts readers why the writer’s thoughts on the topic matter in the context of a larger conversation. For example, students often write papers on why they think schools should not have uniforms. However, they only include their opinion on the topic and do not set up their paper as part of a larger conversation. By including ‘they say’ first, writers alert readers that their opinion is important because it is in response to a critic. Graff and Birkenstein admit that placing the ‘They Say’ component first is contrary to traditional writing instruction. Traditional writing instruction begins with writers expressing their claim first and then supporting it with evidence and defending it against counterarguments. The unique arrangement of They Say I Say forces the writer to always remember that writing is a form of communication. Because writers are communicating, they should not present their ideas in isolation but rather as a response to a conversation. They Say Methods You can introduce what they say as: Suammarizing what 'They Say' Quoting what 'They Say' A standard view Something you say Something implied or assumed Part of an ongoing debate Summaries Quotes Require close reading Require precise verbs Temporarily suspend your perspective Prevent fallacious reasoning Can be satiric if you disagree PART 2: ADD ‘I SAY’: MOVES TO RESPOND *Summary adapted from Rodgers, Springer, Cromwell, Harris, and Dole Must be properly introduced Need to have their importance explained Should support your argument Must be a combination of the author’s words and yours Once students can successfully identify and examine the claims on either side of an argument, they are ready to make their own assertion—the “I Say” component. When students are making their own claim, Graff and Birkenstein suggest there are only three basic directions the claim can take. They can agree with an argument given in the “they say” component, they can disagree with that argument, or they can agree with stipulations—the “yes, but” claim. Many students struggle as they construct a claim, only considering their gut reactions and opinions of the topic. This template forces students to enter the bigger debate and to couch their claim in the evidence already provided by others. This matches the direction of the Common Core State Standards, which switch from simple opinion writing to argumentation based in evidence as students move into the middle grade level. Note that it’s important to teach students that it isn’t enough to just agree or disagree—they must include reasons for why they are taking their chosen side. Otherwise, they aren’t adding to the academic conversation; they are just repeating or refuting what someone else said. Once they have established their “I Say,” they can add another argument move from “They Say I Say,” what Graff and Berkenstein call planting a naysayer in your text. The same move, can be found beginning in grade 7 of the CCSS Writing Standards, where students are required to “acknowledge alternate or opposing claims.” Since the focus of “They Say I Say” is on entering into a larger dialogue about a topic, planting a naysayer allows students to consider opposing viewpoints and expand their understanding of the issue at hand. A successful refutation of the naysayer requires acute critical thinking—students must see beyond their own perspectives in order to find reputable arguments to oppose the naysayer. I Say Methods: Yes; No; Okay, but... Introducing What I Say Distinguish what you say from what they say Use “voice markers” Is it ok to use I? So what? Who cares? Planting a Naysayer And yet... Saying Why It Matters Counterarguments Should address specific groups if possible Can be framed as questions Must be represented fairly Should be answered with a better argument *Summary adapted from Rodgers, Springer, Cromwell, Harris, and Dole Addresses the changing in thinking of interested parties Links your argument to larger matters of importance