Social Darwinism, Populism and Progressivism

advertisement

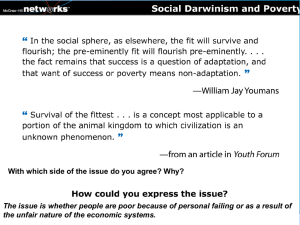

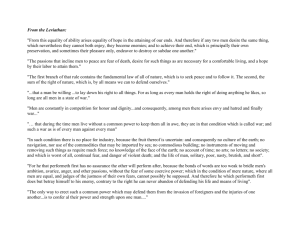

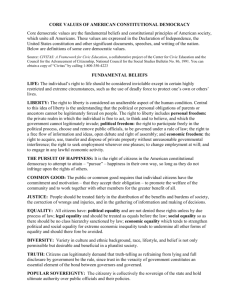

Katie Skaggs POLS 428 William Lund 11 May 2011 Social Darwinism, Populism, and Progressivism The sweeping changes the United States experienced during the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century occurred throughout four “revolutions,” concerning both social and economic sectors. The first of these transformed a subsistence agricultural system into a cashcrop, profit based system that exposed “farmers to markets, the business cycle, monopolies, and politics” (688). The second revolution saw the formation of a working class, which consisted of subsistence farmers and newly-arrived European immigrants. In order to “cope with market forces, these workers began to develop unions (688). The mechanization of industry characterized the third revolution; the development of railroads allowed newly developed assembly lines and conveyor belts to churn out products at a rapid rate (688). The final of these four revolutions “was the revolutionary advancement of capitalism, which brought the other three together in the greatest economic boom in world history” (688). Many schools of thought and political ideals developed to deal with these massive changes. The three most influential of these movements, both at the time and in terms of politics today, were Social Darwinism, Populism, and Progressivism. All three of these, while obviously influenced by each other, had extremely different stances on the role government should play in society and the responsibilities of said government. The first to coin the phrase “survival of the fittest,” Herbert Spencer can be credited with the establishment of the concept of Social Darwinism. He combined the ideals of economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo with the “evolutionary theory of Charles Darwin” to argue that “economic competition must be left ungoverned…because free competition among autonomous individuals was a necessary condition for progress” (691). Essentially, Spencer advocated against any governmental intervention in the regulation of the economy (laissez-faire), as well as against any government financial aid for the poor. In order for society, and the human race as a whole, to progress, the poor must be eliminated because they are unfit to survive and must make room for “the better” (Lecture Notes). As William Graham Sumner, a disciple of Spencer, “we cannot go outside of this alternative: liberty, inequality, survival of the fittest; not—liberty, equality, survival of the unfittest. The former carries society forward and favors its best members; the latter carries society downward and favors all its worst members” (725-26). Sumner argued that for the government to provide financial aid to the poor infringed upon basic civil liberties, and should thus be avoided. The entire philosophy of the Social Darwinists can basically be summed up by his statement that “What civil liberty does is to turn the competition of man with man from violence and brute force into an industrial competition under which men vie with one another for the acquisition of material goods by industry, energy, skill, frugality, prudence, temperance, and other industrial virtues” (726). A major supporter of Spencer’s school of thought was one of the best-known “robberbarons” of the time period, Andrew Carnegie, who advocated economic competition against all else. However, it is interesting to note that Carnegie eventually distributed much of his massive fortune through philanthropic donations to many different institutions. A stark contrast to the ideals of Social Darwinism, the Populist Movement advocated for ordinary people, pitting them against the elite. Developed as a response to the concept of Social Darwinism, which centered on industry and economic competition, the Populist Movement advocated for agriculture, farmers, and ordinary people. Pitting “the people” against “the elite,” the idea of Populism grew out of agrarian unrest throughout the country. Though the agricultural sector had grown immensely from subsistence farming to producing cash crops, farmers still suffered financial, partly because of unregulated inflation. Unlike Social Darwinists, who all advocated essentially the same thing, there is a great deal of variety within Populists. While all advocated bigger government with more economic regulation, different Populists had different ideas for how this should be implemented and in terms of what exactly the government should do. Essentially, Populists believed in equality for all in a way that the Social Darwinists scorned. A main proponent these ideas was the social critic Henry George, who observed that “as wealth increases, so does poverty, at an equal or greater rate” in his widely read Progress and Poverty (690). A self-educated man, George “attributed the poverty of most Americans to regressive land policies,” and advocated abolishing all taxes, except one (740). This remaining tax would be on “the unearned profit obtained from rising land values caused not by improvement, but by increased demand through population growth,” and the massive revenues from this tax should go towards various “socially beneficial public works” (741). While the idea of this tax was unique to George, it epitomized the way that the Populists were different from the Social Darwinists; this plan would charge money from the few to benefit the many. His stance on equality is far different than that of men like Sumner and Carnegie; as George puts it, “There is but one way to remove an evil—and that is, to remove its cause. Poverty deepens as wealth increases, and wages are forced down while productive power grows…to extirpate poverty…we must therefore substitute for the individual ownership of land a common ownership” (743). Because it would be unjust for the government to confiscate or purchase the land, George’s solution is the tax, essentially “rent” for the land. In terms of liberty, equality, and competition George’s stance is clear: “Equality of political rights will not compensate…political liberty, when the equal right to land is denied, becomes…merely the liberty to compete for employment at starvation wages” (746). He continues with “we cannot go on permitting men to vote and forcing them to tramp. We cannot go on educating boys and girls in our public schools and then refusing them the right to earn an honest living. We cannot go on parting of the inalienable rights of man and then denying the inalienable rights of the bounty of the Creator” (747). Another Populist during this time period was Edward Bellamy, a social critic and writer who advocated the nationalization of large industries and public services and denounced the “ruthless competition of the Gilded Age” (747). Another reformer of the time was Henry Demarest Lloyd who used his book, Wealth Against Commonwealth, to describe the “socially destructive effects of industrial monopolies,” specifically the Standard Oil Company owned by robber baron John Rockefeller. Lloyd rejected the “laissez-faire ideology of individual selfinterest in favor of a political approach that acknowledges the interdependence of individuals,” stating that “liberty produces wealth, and wealth destroys liberty” (764-65). He was convinced that they business system of the 1890’s, that of overwhelming monopolies could not be sustained, referring to the “visibly impending failure” (769). The questions raised by the Social Darwinists and the Populists are something that this country continues to struggle with today. Boiled down extremely simply, one could loosely compare Social Darwinists (to a very minimal extent) to Republicans, who continue to advocate competition and support big business, while Populists could be considered Democrats in that they spoke for the “little people,” encouraging government involvement to ensure equality for all. However, these two movements do not have as much relevance to today’s society as the another. The final major reform movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was that of the Progressives, which developed to combat the ills of American society that developed during the country’s period of massive industrial growth. Of the three, this movement has overwhelmingly influenced American politics today in many ways. As the longest running and most influential of the reform movements of this time, the Progressive Era boasts many prominent authors and political figures. Perhaps the most important focus of this movement revolved around the political machines in the big cities throughout the country and the ensuing corruption that ran rampant. One critic of these machines was Lincoln Stefffens, who published The Shame of the Cities in order to denounce them, asserting that “politics is business,” and saying that until “the demand for good government increased, businessmen would continue to see politics as a way to promote their self-interest at the expense of the public good” (988). The eventual abolishment of the machines led to radically decreased corruption and the civil service system we have in place in government today, which in turn led to increased accountability and improved performance. While the machines were a major focus of Progressives, they pushed for reform in nearly every aspect of American politics and life. The famous Progressive author Upton Sinclair used his book The Jungle to expose the need for better working conditions and food regulations, which succeeded; the first Pure Food Act was passed as a response (993). Sinclair also used his writing to comment on the “noxious effects of capitalism and political corruption” (993). Equality was another favorite topic for Progressives; a huge advocate of equality through the establishment of the minimum wage was Monsignor John Ryan. His argument was based on the fact that “Catholic doctrine required that each person be guaranteed a proper share of the social product” (1001). Like Sinclair, Ryan was successful in enacting change; many of his proposals were eventually enacted into law under Franklin D. Roosevelt (1001). Jane Addams embodied the spirit of reform that took root during the Progressive era; she “championed juvenile justice, hosing reform, municipal reform, workplace safety, women’s suffrage, and an eight-hour workday for women” and believed that “public provision of recreation and cultural activated could…rejuvenate morals among urban youth” (1002). All Progressive reformists believed that the government should do more to enable the enactment of reforms relating to their various causes, though, like with the Populists, their methods varied. For example, Walter Rauschenbusch, a Baptist minister, believed that the “church should work with the state to improve social conditions in order ‘to transform humanity into the kingdom of God,’” which was the foundation of the Social Gospel movement (1007). In all, the Progressive movement resulted in sweeping reforms across nearly every aspect of American life, and we continue to feel their effects today. Though these three movements had very different goals, especially Social Darwinism, they all served to shape the American political climate and everyday life, both then and today.