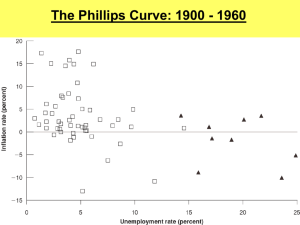

Unemployment and Inflation – Part 13

advertisement