Counseling

advertisement

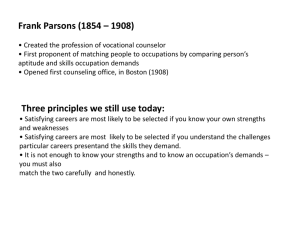

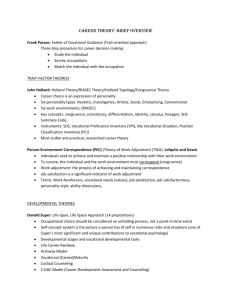

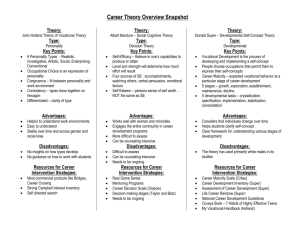

1 Outline 1. Career counseling – until recently, unnecessary 2. What changed? 3. Measuring vocational interests 4. Issues in measurement 5. Trait factor approach 6. Other approaches 2 Career counseling – until recently, unnecessary • Until about 100 years ago, this concept (career counseling) didn’t exist • If you were a boy, your job was what your father’s job had been – which was specified by your surname – or you could join the army • If you were a girl, you would become someone’s wife or servant 3 What changed? • Agricultural equipment • Fewer workers needed on farms because new machines vastly increased productivity • So people who would have been farm workers needed something else to do 4 What changed? • Industrial revolution – • More workers needed in cities, where they lost touch with their ancestral occupations • Jobs involving machinery were mentally challenging so some people were more suited than others to a given task 5 What changed? • 19th and early 20th C immigration to North America from Europe • Immigrants lost touch with ancient lifestyles, fathers’ occupations • Immigrants were likely to be people who were not afraid of change 6 What changed? • Late 1800s – roads leading from rural areas into cities built throughout USA and Canada • Built by large railroads, so people could get from farms into cities, thus to train stations for inter-city travel • Side effect: these roads let rural children get to city schools to be educated 7 Career counseling – why is it necessary? • While all this was going on, North Americans were becoming more productive and thus wealthier • They could afford to educate their children • They could also afford to develop a psychological testing industry to guide career choices • Guidance needed because choice of careers ballooned 8 Frank Parsons (1854 – 1908) • Created the profession of vocational counselor • First proponent of matching people to occupations by comparing person’s aptitude and skills occupation demands • Opened first counseling office, in Boston (1908) 9 Frank Parsons (1854 – 1908) • Three principles we still use today: • Satisfying careers are most likely to be selected if you know your own strengths and weaknesses 10 Frank Parsons (1854 – 1908) • Three principles we still use today: • Satisfying careers are most likely to be selected if you understand the challenges particular careers present and the skills they demand. 11 Frank Parsons (1854 – 1908) • Three principles we still use today: • It is not enough to know your strengths and to know an occupation’s demands – you must also match the two carefully and honestly. 12 Online resources you might find useful • • • • O*Net Online Myskillsprofile Jackson Vocational Interest Survey Career Centre at Western 13 Measuring vocational interests • • • • • • The Strong Vocational Interest Blank (SVIB) The Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory (SCII) Holland’s RIASEC Codes The Campbell Interest and Skill Survey (CISS) Kuder Occupational Interest Survey (KOIS) Jackson Vocational Interest Survey (JVIS) 14 Cautionary notes • Interests vs. abilities – Holland: interests are determined by personality • Clinical vs. actuarial judgment – Meehl: clinical is better • Traits vs. situations 15 Strong Vocational Interest Blank • Edward Strong (1884 – 1963) • B.S. (Biology) 1906 UC • Ph.D. 1911 (Columbia) • Professor at Stanford from 1923 • Vocational Interests of Men and Women (1944) "When I began working on interest measurement," Dr. Strong once remarked, "no one believed you could build scales to measure interests, or that such scales would yield any kind of stable scores. As a matter of fact, I didn't really believe it myself until I had been working on my test for several years. Each time we got a new occupational group tested, I fully expected to discover that we couldn't differentiate it on an interest basis, and that the whole concept of interest measurement would fall apart… "What really convinced me emotionally that we had something was a personal experience. My son had been an indifferent student in college and had no idea what he wanted to do vocationally. He took my test and came out with an A on Physician, an occupation he had never considered entering. Well, he went to medical school, got straight A's throughout, and has been a dedicated and successful physician ever since. I began to think maybe we had a method that would really help young people find where they belonged." Strong (1944) (emphasis added) 17 Strong Vocational Interest Blank • First published in 1927 with 420 items reflecting 10 Occupational Scales • New editions in 1938 and 1946 • 1960 Basic Interest scales added • 1974 Holland Codes added • 1994 Strong Interest Inventory (now 317 items) 18 Strong Vocational Interest Blank • Criterion keying – begin by identifying activities liked or disliked by people in different occupations • Patterns of interest remain stable over time • Do some interests mark an occupation? If so, interests can be used to guide career choice 19 Strong Vocational Interest Blank • Basic Interest Scale: – Identifies groups of occupations that share some qualities that you might be interested in – Gives a general direction – e.g., “You should work with people” • Occupational Scale: – 211 occupations – Separate scales for men and women 20 Strong Vocational Interest Blank • Personal Style Scale: – Prefer to work alone or with people? – Practical knowledge or learning for its own sake? • Personal Style Scale: – Careful or quick decision making? – Risk-taking? – Team orientation (achieve goals by working with others)? 21 Strong Vocational Interest Blank • Criticisms: – Sex bias? – No theory • Strengths: – High reliability: Internal consistency reliability in high .80s – Test-retest reliability (up to 6 months between tests) in .80s 22 Strong Vocational Interest Blank • Strengths: • High validity • Assesses interests among a wide variety of hobbies, academic subjects, work activities, occupations • Sample for comparisons – includes impressive variety of ethnic, social, and educational backgrounds 23 Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory • Campbell continued development of Strong’s SVIB • Most widely used interest test • No sex bias • Includes J. L. Holland’s theory of vocational choice. 24 Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory • Test taker responds to each item: Like, Dislike, or Indifferent • Yields 4 different scores 1. 2. 3. 4. Holland’s Personality Types Administration Basic Interests Occupational 25 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Holland: Occupational interests reflect interaction between personality and environment. • "People search for environments that will let them exercise their skills and abilities, express their attitudes and values, and take on agreeable problems and roles." (Holland, 1997) 26 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Holland – 6 personality types: • • • • • • Realistic Investigative Artistic Social Enterprising Conventional 27 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Holland – another set of labels that may help you remember the different types • • • • • • Doer (R) Thinker (I) Creator (A) Helper (S) Persuader (E) Organizer (C) 28 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Realistic • • • • • • Less social Like the outdoors Like manual activities Physically robust Practical Non-intellectual 29 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Investigative • Interested in ideas more than people • Not very social • Dislikes emotional situations • Appears aloof 30 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Artistic • • • • • • Creative Enjoys developing ideas Enjoys expression Dislikes conformity Comfortable with ambiguity Not especially skilled socially 31 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Social • Likes to work with other people • Helping orientation • Nurturing 32 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Enterprising • People oriented • Goal oriented • Good at coordinating work of others 33 Holland’s RIASEC Codes • Conventional • Does best in highly structured situations and jobs • Good with details • Likes clerical tasks, working with numbers • Doesn’t like working with ideas or people 34 The Campbell Interest and Skill Survey • 1992 • Also uses Holland’s theoretical structure • Extroversion and academic focus scales • Assesses skill as well as interest 35 The Campbell Interest and Skill Survey • Depending on combination of degree of interest and skill, the test-taker is advised to: • Pursue (high interest, high skill) • Develop (HI,LS) • Explore (LI,HS) • Avoid (LI,LS) 36 Kuder Occupational Interest Survey • Second most widely used interest test • Criterion keying method • Measure = 100 triads of alternative activities • For each triad, test-taker selects most/least preferred 37 Kuder Occupational Interest Survey • Dependability • Interest Scores • Relation of interest patterns to norms of men and women 38 Kuder Occupational Interest Survey • Occupation Scores • Relation to scores of men and women employed and satisfied in certain occupations 39 Kuder Occupational Interest Survey • College major scores • Relation to scores of students in different college majors 40 Jackson Vocational Interest Survey • Douglas Jackson (-) was for many years a professor in the Department of Psychology at UWO 41 Jackson Vocational Interest Survey • Matches people to academic or career fields based on their interests • 289 pairs of statements describe job activities • Forced choice for each pair • Does not compare scores to those of people happy in their occupation • Yields 34 basic interest scores • Predicts university majors more accurately than most inventories 42 Jackson Vocational Interest Survey • Basic Interest Scales – some examples (not a complete list): • • • • • • • • Creative Arts Physical Science Engineering Life Science Social Science Adventure Nature-Agriculture Skilled Trades 43 Jackson Vocational Interest Survey • General occupational themes (G.O.T.) • • • • • • • • • • Assertive Communicative Conventional Enterprising Expressive Helping Inquiring Logical Practical Socialized 44 JVIS – Basic Interest Scales Reliability • Internal consistency reliability (alpha) .54 to .88. • Test-retest reliability (4 to 6 weeks) .69 to .92. 45 JVIS – G.O.T. Reliability • Internal consistency reliability (alpha) .70 to 92. • Test-retest reliability (4 to 6 weeks) .83 to .93 46 Minnesota Vocational Interest Inventory • Criterion keying, no theoretical base • Aimed at men not oriented towards college • Emphasizes skilled/semiskilled trades • Yields basic interest and occupational scores 47 The Career Assessment Inventory • Intended purpose similar to that of MVII • 6th grade reading level • Sex- and culture-bias free • Includes Holland’s theoretical base • Scores on scales similar to SCII and CISS 48 The Career Assessment Inventory • Vocational version • 305 items, 91 occupations that require little postsecondary education • Enhanced version • 370 items, 111 occupations including some that require significant post-secondary education 49 The Self Directed Approach • Self administered, scored, interpreted • Rate skill and interest in occupational areas • Linked to an occupation finder • Accurate scoring • Lets user develop a ‘personal career theory’ 50 Issues in Interest Measurement • Sex bias – Leads people to sex-typed careers – But elimination might mean lower validity – Most scales today have reduced bias • We should examine tests for sex bias and try to remove it if found, but… • Women and men are different in a variety of psychological and physiological ways • Differences in which careers are suggested may not result from “bias” 51 Issues in Interest Measurement • Note the difference between data and interpretation: • Data – some tests suggest different occupations for men and women • Interpretation 1 – men and women genuinely differ in interests and thus in preferred occupations • Interpretation 2 – the test is biased • Either or both might be true… 52 Issues in Interest Measurement • Interests vs. aptitudes • E.g., in Strong inventories, how successful in their occupations are the norm groups expressing particular interests? 53 Issues in Interest Measurement • Development – Does it matter for testing that people change in ways relevant to occupational success? • Personality is stable over the lifetime • But other things – motivation, education, environment – will surely change and interests may change with them 54 Osipow’s trait-factor approach • Goal is to learn about person’s overall traits, not just their interests • Battery of tests covering – – – – Personality Ability / Aptitudes Interests Values 55 Super’s Developmental Theory • Suitability for a career is not static • Developmental stages define what vocational behavior is expected of us • Vocational maturity is defined as the correlation between actual and expected vocational behavior – Actual comes from developmental stage you’re in 56 Super’s Developmental Theory • Super (1954) Theory of vocational choice – lifespan developmental process 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Crystallization Specification Implementation Stabilization Consolidation Ready to retire 57 Ginzberg et al. (1951) • Ginzberg et al. (1951) – career choice is the outcome of a developmental path from childhood to young adulthood – stages: • Fantasy • Tentative • Realistic – Exploration – Crystallization – Specification 58 Roe’s Career Choice Theory • Roe: career choice a result of type of relationship you had with your family while growing up • Relationship success leaves you with a personorientation • Relationship failure, leaves you with a non-person orientation 59 Roe’s Career Choice Theory • As a result of rearing, some people are oriented towards other people • they were reared in a warm, accepting environment 60 Roe’s Career Choice Theory • As a result of rearing, some people are oriented towards things • they were reared in a cold, aloof environment. • Characteristics measured by California Occupational Preference Survey (COPS) 61 Caution Text, p. 472 “Despite the availability of many interest inventories, old-fashioned clinical skill remains an important asset in career-counseling.” • There is lots of evidence that this claim is not true – in the work of Paul Meehl and others on clinical vs. actuarial judgment