Music of Russia - Madison Central High School

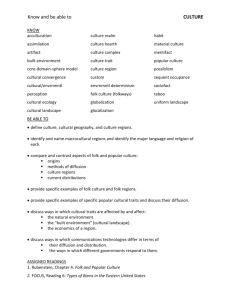

Music of Russia

USAD 2012-2013

Folk Music

Folk songs varied locally from region to region

Different villages sang different songs

¨ They also sang different variations of the same song

Urban assimilation of villages transformed folk songs

¨ In some cases, urban popular music obliterated folk tradition

The late 18th century gave rise to folk song transcription

Educated urban gentlemen spearheaded the notation of folk music

Many of these men were amateur musicians

Their work introduced folk songs into the world of art music

Transcription

Scotland pioneered transcription, but Germany performed most important legwork

Achim von Arnim (1781-1831) and Clemens

Brentano (1778-1842) compiled Des Knaben

Wunderhorn (1805-1808)

¨ This folk song collection only included song lyrics

¨ However, ensuing anthologies often featured melodies as well

Johann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) linked folk songs and nationalism

This German philosopher traveled through Europe and Russia

He believed national divisions existed based on language

Herder considered folk song part of the national, not just local, culture

He was one of the first to note the national importance of folk music

Herder wrote that folk music channeled national spirit

Folk songs became part of national heritage

Transcription methods and their flaws

Before audio recording, transcribers relied solely on their memories

Circumstances did not always allow the transcriber to hear the song multiple times

Even if he did, the same singer might still vary the song

Folk tradition did not stress rigid adherence to pitch and rhythm

Peasants only performed certain songs on certain occasions

Many folk songs were tied to ritual or work-related events

Thus, the transcriber only had one chance to listen

These events, like weddings, often came with distractions as well

Problems cont’d

The extensive lyrics took a long time to perform

Many publishers only printed excerpts from songs

A nonsensical verse about nature might have led to a profound tale of love

Worse yet, publishers rarely indicated these omissions to the reader

Some scholarly works generally included full texts

However, the general public could not easily access these publications

Even with the help of audio recording, transcribers must still make choices

Transcribers must decide which irregularities to preserve and which to exclude

Problems cont’d

Early transcribers did not bother themselves with issues of authenticity

Above all, these transcribers viewed folk songs as market goods

Transcriptions needed to appeal to domestic consumers

Most arrangements involved solo voice and piano

Arrangers ignored or rewrote polyphony and heterophony

These textures greatly differed from Western art music

Arrangers feared buyers would not approve

Sometimes arrangers replaced Western-like idioms to increase “folk” appeal

Notated folk songs reflected urban expectation more than rural tradition

More Problems with transcriptions

Despite their claims, arrangers always invented their own harmonies for folk melodies

The original songs most often involved only solo voice

However, arrangers still claimed to use

“authentic” harmonies

20th-century arrangers became more conscious of authenticity and accuracy

Track 1: “The Day was Breaking”

This folk song derives from the Smolensk region

“The Day was Breaking” exemplifies the

protyazhnaya genre

It features a long, winding melody

The melody is melismatic

Each syllable stretches out over an entire musical phrase

Thus, the lyrics unfold incredibly slowly

The lyrics refer to army recruitment

Russian conscripts served in the Tsarist army for

25 years

“The Day was Breaking” cont’d - excerpt

Each verse begins with a zapev, or solo introduction

The zapev centers on the interval of the fifth

Protyazhnayas often focus on this interval

Mikhail Glinka described the fifth as “the soul of

Russian music”

Podgoloski (“undervoices”) overwhelm the zapev, thickening the texture

Each ensuing verse becomes more dissonant

At the end of each verse, the texture reverts to unison

“The Day was Breaking” cont’d - excerpt

The song takes liberties with intervals

At the outset, a minor third featuring the modal center and the third scale degree appears

However, at the end of each verse, a major third appears

This interval sounds widely tuned compared to

Western music

19th century collectors would dismiss the sound

However, 20th century collectors indicated the wider tuning in their notation

The singers use “open” sounds, just as real folk singers do

Overview

Various types of “Russian folk songs” pervade the musical world

Examples include “Dark Eyes,” “Those Were the Days, My

Friend,” and “Coachman, Spare Your Horses”

A few songs originated in the countryside

19th-century Russian restaurants often featured gypsy singers and choirs

Their repertoire included both true folk songs and urbancreated “folk” songs

Most 18th- and 19th-century collectors focused on notating legitimately rural folk songs

These songs reflected local village traditions and rituals

However, collections did include the occasional popular song

Scholars classify folk songs into genres

They base these decisions based on the song’s function

They also consider the lyrics and character of the song

Protyazhnaya

A solo performer may sing a lyrical song without a special occasion

These songs often focus on a tale of unhappy love

The best-known subgenre of lyrical songs is the protyazhnaya

Protyazhnaya literally means “prolonged”

A protyazhnaya typically features a long, winding melodic line

The melismatic aspect of the songs further increases their length

Melismatic songs stretch each syllable over a musical phrase

Even native Russian speakers struggle to piece together the slowly unfolding lyrics

The protyazhnaya took on great symbolic status in the 19th century

Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852) established the protyazhnaya as a symbol for Russia as a whole

His novel Dead Souls (1842) includes a memorable image

Three horses lead a coach across an unending stretch of

Russian land

The coachman sings a melancholic, interminable protyazhnaya

Thus, Gogol implies that both Russia and the protyazhnaya are endless and tragic

Many people came to believe all Russian folk songs sounded melancholy

City dwellers encountered the protyazhnaya more frequently than other folk genres

Calendar Songs

Rural peasants only performed calendar songs for certain seasonal rituals

These occasions include Advent, Christmas, Shrovetide, and the summer solstice

The lyrics of these songs often combine pagan and

Christian symbols

Many Christian festivals replaced earlier pagan holidays

Calendar songs differ significantly from protyazhnaya songs

Scholars believe calendar songs are much older than lyrical ones

Calendar songs use shorter, more syllabic melodic phrases

Each pitch corresponds to a single syllable of text

Other folk genres

Wedding songs included joyous hymns and more depressing tunes

Tradition required the bride to sing a song lamenting leaving her parental home

Funeral laments featured naturalistic sobbing sounds

The North of Russia favored byliny, or epic songs

These solo tunes recounted ancient legends and historical events

Byliny were syllabic and imitated human speech

Labor songs helped coordinate group labor projects

Barge workers sang the “Song of the Volga Boatmen”

The rhythm allowed the many workers to pull ropes simultaneously

Plyasovye refers to energetic dance songs

These repetitive melodies featured strong rhythms

Other genres included lullabies, game songs, and military marches

“Akh ty step”

V. Sokolov arranged this Russian folk song

The song reflects popular (urban) elements rather than true rural roots

Three aspects of the song reveal its classification as a protyazhnaya

Many songs of this genre feature the same opening line: “O, ye steppes…”

The melody features wide intervals

The opening starts with an ascending sixth

Later, we hear an ascending octave

Like other protyazhnayas, the song sounds lyrical and sorrowful

“Akh ty step” cont’d

“Akh ty step” clearly displays urban influence

This arrangement is much less melismatic than traditional folk songs

Urban styles override folk-like variants and irregular harmonies

The modern choral arrangement adds a hummed introduction and a lengthy conclusion

However, the arranger does attempt to imitate folk devices

Some of the four verses begin with expressive vocal solos

Middle voices actively participate in the harmony

The ends of phrases often converge to a unison or octave

Folk Songs Collections &

Arrangements

Lvov-Pratsch (1790)

The Lvov-Pratsch collection was the most influential early folk song anthology

It included both text and music

Nikolai Lvov transcribed the text

Johann (Ivan) Pratsch arranged the music

City dwellers used the collection for domestic music playing

Composers included the arranged melodies in their own works

Lvov-Pratsch cont’d

Accusations of Westernization contributed to the collection’s fall from grace

Critics charged Pratsch with rewriting melodies to match urban expectation

Pratsch supposedly placed accents on the wrong syllables to match Western meter

Later musicians found Pratsch’s harmonizations insensitive and Western67

Lvov did not keep records of his sources

The sources may already have been altered from the rural originals

Thus, scholars cannot know the extent of Pratsch’s changes

In the 19th century, collectors became more conscious of accuracy and authenticity

Balakirev (1866)

The Balakirev collection stressed the distinctive sound of Russian folk music

Unlike Pratsch, Mily Balakirev did not try to urbanize folk melodies

Rather, he attempted to exaggerate the differences between folk and art music

This choice reveals the abrupt shift in consumer taste in the 19th century

Balakirev favored non-Western musical ideas and simple harmonies

He often used flattened seventh degrees instead of

Western leading tones

Sometimes he misrepresented sources to emphasize non-

Western sounds

Balakirev cont’d

Balakirev mostly employed diatonic harmonies

In other words, he only used the pitches of a single scale

Other than hymns, Western art music did not typically do this

These harmonies created a modal sound

He used triads rather than four-note chords

From 1600 onward, seventh chords frequently appeared in

Western art music

Balakirev believed folk music should sound more ancient

Balakirev also meticulously adhered to the natural stress pattern of words

He varied meter rather than sacrifice the stress pattern

Despite his scrupulous methodology, Balakirev still produced arrangements

In other words, the transcriptions did not accurately reflect folk practice

However, they were more accurate than Pratsch’s approach

Melgunov and Palchikov

Before the late 19th century, collectors did not transcribe polyphony or heterophony

Heterophony involves unsynchronized singers performing the same melody

It can also refer to a single melody with simultaneous variations

Polyphony refers to simultaneous melodies

Russian folk collectors were not very aware of these textures in folk song

Few early transcribers made serious attempts to notate them

Composers imitated the effect vaguely, but few understood the texture well

They began folk-like choruses with a soloist

They then incorporated the rest of the choir

The section ended in unison

Composers only became aware of these two textures after recording technology appeared

Yuli Melgunov & Nikolai Palchikov cont’d

Yuli Melgunov and Nikolai Palchikov each attempted to notate folk heterophony and polyphony before recording technology

Melgunov published his collection of folk songs in 1879

He succeeded in notating heterophony

To do so, he listened to the music in melodic, not harmonic, terms

He listened to several singers in the same village performing one at a time

Then he combined these variations on a single melody into one score

His attempts did not truly transcribe a choral folk song

However, they served as good approximations of heterophony

Composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov dismissed the collection as “barbaric”

He could not bear the heterophonic texture

The idea contradicted his own method of harmonizing folk songs

Yuli Melgunov & Nikolai Palchikov cont’d

Nikolai Palchikov produced the best notation of folk polyphony

Palchikov lived in a village

Thus, he could observe the same songs and singers multiple times

Unfortunately, he also remained in relative obscurity

Palchikov stood next to each singer and notated each part

He then combined these separate lines into a score

The result proved better than Melgunov’s compilation

Unfortunately, Melgunov’s collection received greater attention

Melgunov’s arrangements introduced Russian folk texture to the art world

Linyova (1904)

Yevgeniya Linyova released her first folk song collection in 1904

She spearheaded the use of audio recording technology

Now, composers could not deny the textures in

Russian folk music

Composer Igor Stravinsky was the first to embrace these folk textures

Other 20th century composers eagerly followed his lead

At the time, composers longed to break established composition rules

Folk Songs in Classical Music

Composers’ uses for folk song

Composers used folk themes to characterize lower-class characters in operas

For instance, Mikhail Glinka used folk songs to designate peasants in A Life for the Tsar

Other composers believed folk melodies made music sound more “national”

Philosophers like Herder reinforced this belief

Glinka chose Russian folk songs to differentiate his work from

Italian operas

The use of familiar folk melodies also garnered sympathy and acclaim from audiences

Folk music also contained new techniques

Glinka and other composers drew inspiration for technical innovations

Composers often included folk melodies for several of the above reasons

Folk Songs in Classical Music cont’d

Myths and exaggerations

Many “national” composers exaggerated their knowledge of folk traditions

Often, their biographers published gross overstatements

In truth, most 19th-century composers came from privileged backgrounds

They did not grow up listening to folk music

Most composers consciously studied folk music in their adult years

Rimsky-Korsakov himself denied rumors of his familiarity with folk songs

He did not experience folk music until his twenties

Rimsky-Korsakov studied Balakirev’s collection of transcriptions

Contemporary critics often exaggerated the authenticity of quoted folk songs

Composers rewrote folk melodies to suit their own works

The songs themselves transformed en route from the village to the city

Rimsky-Korsakov presented a folk song melody simply

He often used a solo woodwind instrument

The accompaniment consisted of subtle string pizzicato

Rimsky-Korsakov kept harmony to a minimum, using long pedal notes

A pedal note refers to a long sustained note, often found in the bass line. Usually, a pedal note contains the root of the harmony.

Audiences frequently believed all folk songs sounded like this

However, the style was all Rimsky-Korsakov’s creation

Most importantly, scholars overplayed the national spirit imparted by folk songs

Only peasants from a certain region would recognize a folk song

Yet composers came to associate folk song with the entire population of Russia

In other words, a tiny little-known part represents the vast whole

Folk music does not possess noticeable

“Russianness”

A foreign audience unfamiliar with Russian music would not recognize it as such

Russian Music of the 19

th

century

Westernization and Russian

National Identity

Westernization under Peter the Great

In the early modern period, Russians set themselves apart from “The West”

Ivan the Terrible (r. 1547-1584) allegedly sent several dozens of scholars abroad

Unfortunately, none of these students ever returned to share their learning

Before Peter the Great, Russia rarely contacted

Europe

Russia occasionally sent diplomats overseas

But, the country did not engage in extended interaction with the West

Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725) began a largescale Westernization program

During his reign, the educated elite increasingly realized Russia’s isolation from the West

This epiphany also spread throughout the general population

European civilization fascinated Peter

He traveled throughout Europe in disguise

At one point, the tsar worked as a shipbuilder on a

Dutch wharf

Peter the Great aimed to recreate Russia as a major European power

He intended to establish an irreversible, largescale program of Westernization

St. Petersburg

• St. Petersburg became the thriving center of Peter’s “new and improved” Russia

• Engineers and laborers drained a strategically located marsh to build the city

• The tsar based the city on

Venice and Amsterdam

• St. Petersburg featured its own harbor and canals

• It contained towering modern buildings

• The Europeanized city did not look like any other

Russian town

Peter Westernized every aspect of city life

The well-organized grid of streets and identical houses emphasized his power

He renamed and remodeled all state institutions to fit Western models

He forced the aristocracy to adopt European dress and shave their beards

Nobles discarded their long robes in favor of

European breeches and coats

Those who refused to shave were forcibly coerced

Peter also hosted assamblei (fashionable balls) and introduced the minuet ( slow and graceful ballroom dance for two, the minuet first appeared in the

French royal court during the 17th century. Its name derives from the small (menu means “small”) steps required to perform the dance. 18th-century composers often included a minuet-style piece in triple time as a movement in a larger composition.)

Despite heavy resistance, Peter the Great successfully implemented his reforms

In part, he triumphed due to sheer ruthlessness

His alterations, however, did benefit some segments of the population

Still, controversies over Westernization remained for two centuries

Communism later declared itself the supreme

Westernizing force

However, the Soviet Communist movement still diverged from Western ideals

The emergence of Russian nationalism :

Nationalism only gained major momentum in the late 18th century

German nationalist philosophers influenced the educated Russian elite

Both nations worked to collect folk songs

Russians also began to take interest in their native Slavic language

At the time, the urbanized nobility mostly spoke French

The Russian elite viewed nationalism in completely cultural terms at this time

Napoleon Invades

Napoleon’s invasion in 1812 truly launched

Russian nationalistic fervor

Authorities realized that the army required the support of the entire population

Political nationalism first appeared in mass produced patriotic posters and leaflets

These advertisements urged all Russians to unite as a single nation

They asked individuals to pledge their main loyalty to their nation

• The pamphlets succeeded in uniting the Russian population

• Russian peasants fought

French invaders with axes and sticks

• Citizens set fire to Moscow rather than relinquish it to

French forces

• The defeat of Napoleon gave rise to Russian national awareness

Outcomes of the Napoleonic Wars

Though their victory united Russian citizens, the

1812 Patriotic War also fostered dissent

Russian military officers and soldiers realized their country’s backwardness

These men fought Napoleon back to Paris

En route, they noticed the superior infrastructure and greater equality in Europe

They also realized that serfdom was incredibly outdated

(Serfdom refers to exploitation of rural peasants by the landowning nobility. The peasants, called serfs, worked for the wealthy landowners in exchange for legal protection and certain other rights. In essence, serfs lived in a condition of modified slavery, as they received no pay and depended on their landlords for all manner of legal, economic, and social welfare.)

Most European nations had outlawed serfdom centuries prior

Another Outcome: The Decembrist Uprising, 1825

• Dissatisfied soldiers revolted against the new tsar Nicholas

I in December 1825

• The “Decembrists” aimed to incite social reform

• Unfortunately, their revolution failed

• The tsar hanged five of the rebel leaders

• He also exiled many other participants to

Siberia

• Thus, Napoleon’s invasion also revealed growing frustration within Tsarist Russia

Establishment of Russian Nationalism

In 1833, the Russian government established

Official Nationalism

All Russian schools would teach students this new state ideology

Minister of Education Sergei Uvarov introduced the doctrine

He described it with a slogan: “Orthodoxy,

Autocracy, and Nationality”

Orthodoxy referred to the dominant Russian religion, the Orthodox Church

Autocracy embodied the unquestionable absolute sovereignty of the tsar

However, even Uvarov did not truly understand

“Nationality” (narodnost’)

At this point, dissatisfied intellectuals developed the concept of nationalism

The Russian government did not yet see nationalism as a weapon they could employ

Pyotr Chaadayev

Chaadayev’s concerns

Pyotr Chaadayev (1794-1856) expressed concern about Russia’s cultural backwardness

His “Philosophical Letter” of 1829 addressed this issue

Chaadayev noted that European nations shared common history and traditions

Their societies held similar views on justice, law, order, and duty

By contrast, Russia never participated in this community

Thus, Russia lacked these basic

European principles

The authorities refused to publish Chaadayev’s

“Philosophical Letter”

They thought his ideas too controversial

Instead, they declared him insane and treated him as such

Regardless, manuscript copies spread throughout the nation (USAD made this corrections in June.)

‘‘In his land, Peter the Great found only a blank sheet of paper, and he wrote on it: ‘Europe and the West’; since then we have belonged to Europe and the West”

Chaadayev’s work inspired two different ideological groups in the mid-19th century

Westernizers believed Russians was part of Europe

They supported continued imitation of Western traditions

Slavophiles focused on Russia’s “blind, superficial and awkward imitation” of the West

This group advocated the reversal of Peter the Great’s

Westernizing reforms

They called to reinstate communal law and other abolished practices

Slavophiles also wanted to firmly distinguish Russian

Orthodoxy (Eastern Christianity) from Western Christianity

(especially Catholicism)

They claimed Eastern Christians favored authority and faith over logic and reason

Slavophiles also spoke of a new world order led by

Russia, not Europe

Like Chaadayev, many other 19th-century intellectuals compared Russians to Westerners

Most comparisons were to the French and

Germans

The French were old enemies from 1812

Meanwhile, the Germans made up a large part of

St. Petersburg’s high society

Comparison and contrast formed the basis for defining Russian “national character”

However, this method of analysis also resulted in national stereotypes

The French were brilliant but the Russians were profound

The Germans were industrious but the Russians were humane and empathetic

“Russian character” proved nothing but a philosophical construct

Philosophical Influence on Music

19th-century Russian composers sought to differentiate themselves from the West

Glinka attempted to create a new style of opera

He believed Russia displayed greater melancholy than sunny Italy

Thus, Russian opera should be more sorrowful than widespread Italian opera

The Mighty Handful would adopt similar ideas in the

1860s

National stereotypes played a major role in the creation of “Russian style”

From the beginning, composers defined Russian music as non-German

German stereotypes thus became a major factor in

Russian musical development

Class Divisions

A great divide existed between the educated elite and the lower classes

Late 18th-century writers claimed national character stemmed from the lower classes

“The people” (lower-class peasants) made up the majority of the population

Upper-class Russians spoke French and tended toward the cosmopolitan

Catherine the Great (r. 1762-1796) descended from Germans

However, she occasionally wore Russian national garb to tease courtiers

The gentry and the peasantry rarely interacted on a regular basis

Even servants in noble households did not maintain ties to their rural backgrounds

Despite their claims, the elite knew little about the general population

Catherine the Great

Abolition of Serfdom

The abolition of serfdom in 1861 sparked renewed interest in the peasantry

The Peredvizhniki (Russian Realist school) did not idealize peasant life in paintings

The Narodnik (populist) movement inspired intellectuals to move to the countryside

Most narodniks were students who left their city homes to join the peasantry

The narodniks provided education and medical assistance to rural peasants

Peasants often treated the narodniks with indifference or even resentment

Interestingly, the peasants placed more stock in social hierarchy than the wealthy

The appearance of their superiors seemed unnatural

Author Leo Tolstoy worked with peasants on his land

He wore a collarless peasant shirt

However, he still lived off the rent from said peasants

Nikolai Palchikov moved to a village to collect folk song melodies

In the village, he worked as a country judge

The peasants ultimately accepted him and helped him in his transcriptions

• Composer Modest Mussorgsky (1839- 1881) revealed the greatest narodnik influence in art music

• He originally hailed from the landowning gentry

• However, he lost his wealth after the emancipation of the serfs

• Despite his reversal of fortune,

Mussorgsky maintained sympathy for the poor

• He wrote songs presenting different peasant characters

• For instance, his song “Trepak” features a drunk and depressed peasant

• This miserable character falls to the snow to awaits his death

East and West

Even as they defined the West, Russians also explored the East

The Russian empire spanned a huge continuous stretch of land

Finland and Poland formed the Western boundaries

The Black and Caspian Seas lay to the South

Eventually, the empire stretched from the Baltic to the Pacific

“The East” covered many different nationalities and cultures

Still, Russians considered a few regions stereotypically “Eastern”

These included the Caucasus region, Central Asia, and the Far East

Russian soldiers constantly fought tribes in the

Caucasus Mountains and Transcaucasia

These tribes waged war on their conquerors hoping to reassert their independence

Russians stereotyped “the East” just as they did the

West

The East, however, was under Russian control

Russians viewed the East as exotic

These stereotypes affected musical Orientalism80

Expansion into Central Asia also influenced

Orientalism to a lesser extent

The Russian Far East did not influence 19th-century music as much

This region was too distant and relatively unpopulated

Thus, it received little scholarly attention

Perspectives on the role of the East differed

Westernizers dismissed the East entirely

They claimed the region would not contribute to

Russian cultural growth

Slavophiles, by contrast, gladly emphasized the role of the East

They claimed the East influenced Russian fatalism, mysticism, and autocracy

The elite emphasized both the similarities and differences between Russia and the East

They often juxtaposed Russia’s simplicity with the

East’s exotic extravagance

However, Russians also “Orientalized” themselves

They emphasized their differences from the West and similarities to the East

They depicted themselves as “Barbarians” who opposed

Western corruption

Track 3: “The Glory Chorus” from A Life for the Tsar

Background

“The Glory Chorus” comes from the finale of

Glinka’s opera A Life for the Tsar

This opera as a whole exemplifies Official

Nationalism

Different elements in this work illustrate

“Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality"

Featured excerpt

In the score, Glinka identifies “The Glory Chorus” as a “hymnmarch”

The onstage military band emphasizes the martial aspect of the march rhythm

The rhythm imitates a Russian Orthodox chant

This rhythm consists of a half-note followed by two quarter notes

Glinka also uses harmonies unusual for an opera

Outer voices move in parallel thirds

Such harmonies frequently appear in Orthodox hymns

Glinka’s score thus indicates religious and nationalist influences

Like the rest of the opera, “The Glory Chorus” embodies Official

Nationalism

In addition to the “hymn” aspects above, Glinka uses church bells to show Orthodoxy

The church bells also reflect Nationality

The lyrics glorify the first Romanov tsar in keeping with the principle of

Autocracy

Glinka: The Father of Russian Music

Most Russian music histories begin with Mikhail

Ivanovich Glinka (1804-1857)

Virtually all historians agree that true Russian classical music started with Glinka’s work

Many consider his first opera, A Life for the Tsar

(1836), the first Russian national opera

Of course, opera existed in Russia before Glinka

Peter the Great began the development of

Russian art music

He hoped to prove Russia’s status as an international power

His assamblei featured dance music byWestern musicians

Peter hoped to recreate Western-style music as part of his Westernization campaign

Actual opera first appeared in Russia during Tsaritsa Anna’s reign

It began as a foreign import from Italy

In 1731, an Italian company performed

Calandro by Giovanni

Ristori in Moscow

In 1736, Russian musicians collaborated with an

Italian troupe in St.

Petersburg

They performed The

Power of Love and Hate by Francesco Araja

Glinka continued

From then on, opera flourished in Russia

The Russian Imperial Court welcomed Italian and

French troupes

Private opera houses opened in St. Petersburg

This development allowed opera to reach wider audiences

The first Russian-language libretto appeared in

1755

The story centered on the myth of Cephalus and

Procris

Italian instructors trained Russian opera singers

Glinka’s predecessors set the stage for Russian opera composition

Maxim Berezovsky (1745-1777) was the first Russian opera composer to achieve fame

Audiences in Russia and abroad recognized his name

Other opera composers included Yevstigenei Fomin (1761-1800) and Dmitri Bortnyansky (1751-1825)

These Italian-trained composers conformed to accepted Western genres

While studying in Italy, they wrote opera seria (“serious opera”)

These works used mythology as their subject matter

One could not differentiate between the Russian and Italian opera seria

In Russia, these composers created comic operas based on French archetypes

However, the librettos featured Russian language

The composers included distinctly Russian plots and characters

Audiences reacted favorably to the familiar elements

Russian comic operas thus enjoyed considerable popularity

Glinka’s Innovations

Many of Glinka’s “innovations” actually existed in the works of his predecessors

Glinka’s works often incorporated folk melodies

Fomin’s Coachmen at the Relay Station (1787) also reflected folk influence

The opera’s opening chorus imitates a protyazhnaya folk song

The solo singer is eventually joined by the chorus

Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar (1836) focused on a historical, not mythological, subject

The story centers on peasant Ivan Susanin

He gave his own life to save the future Tsar Mikhail Romanov

In 1815, Catarino Cavos premiered an opera based on the same tale

A Venetian by birth, Cavos lived and worked in St. Petersburg

His version of the story remained immensely popular

It took time for Glinka’s opera to step out of Cavos’ shadow

Glinka’s great ambition set him apart from his peers and predecessors

His skilled originality put him on par with his

European contemporaries

These peers included Vincenzo Bellini, Giacomo

Meyerbeer, and Hector Berlioz

A Life for the Tsar featured no spoken dialogue

Every line was sung

It was the first Russian-language opera to attempt such a feat

Cavos’ version featured long sections of spoken text between arias and songs

Glinka’s ambition proves surprising given his upbringing

He lacked any formal composition training86

In fact, Glinka regarded himself as a student even in his late years

Born to landowners, Glinka participated in his uncle’s private orchestra

This ensemble mostly played fashionable overtures

Based on this experience, Glinka might have become a composer of light, elegant songs and dances for aristocratic salons

In his apprenticeship, he did create such works

However, they did not satisfy his lofty aspirations

Glinka honed his skills abroad before returning to dominate Russian opera

In Italy, Glinka studied vocal composition

He could have settled for writing Italian-style arias and operas

However, he dared to dream of a purely Russian operatic form

This Russian opera would draw subject matter from Russian history

It would prove more serious and musically demanding than

Italian opera

Glinka learned more difficult compositional techniques in Germany

There he studied with theorist Siegfried Dehn

In 1834, Glinka returned to Russia after hearing of his father’s death

In Glinka’s last year of life, however, he would return to

Germany to visit Dehn

A Life for the Tsar

Glinka’s first opera, A Life for the Tsar, premiered at the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre in 1836

The opera featured a clearly monarchist message

The storyline implied the divine authority of the

Romanov dynasty

Russia successfully fought off a Polish invasion in

1613

Afterward, the first Romanov tsar took the throne

The peasant Ivan Susanin fooled the Poles to allow the tsar time to escape

When they discovered the deception, the Poles killed Susanin

At the end of the opera, Susanin dies in a forest

The epilogue concludes with a somber march

Afterward, the chorus cries, “Glory to the Tsar!”

Naturally, Tsar Nicholas I supported the performance87

Besides the imperialist storyline, the libretto came from the court itself

Baron Rosen, secretary to Nicholas’ heir Alexander II, wrote the libretto

Following the premiere, Nicholas I showered

Glinka with recognition

He offered the composer a royal ring as a token of favor

Furthermore, he offered Glinka the highest musical position in his court

Despite imperial recognition, Glinka did not write

A Life for the Tsar on commission

He actually composed quite a bit of the music before Rosen completed the libretto

As Glinka intended, A Life for the Tsar sounds distinctly Russian

Glinka first created musical contrast between the Russians and the Poles

He characterized the Poles using two Polish ballroom dances

Russians were familiar with both the polonaise and the mazurka

Both dances involved 3/4 time and dotted rhythms

Glinka used more songlike pieces in 2/4 and 4/4 to illustrate the Russians

In Act III, Glinka dramatically juxtaposed both styles

The Poles demand Susanin’s compliance in a mazurka rhythm

Susanin defies them in a protyazhnaya style

Glinka favored the imitation of folk themes rather than direct quotation

The overture mimics a protyazhnaya

The opera’s “Rowers’ Chorus” also features a protyazhnaya-like melody

Glinka set this melody over a pizzicato string accompaniment

The strings represent the balalaika, a plucked string instrument

In the entire opera, Glinka only quotes two actual folk tunes

The intelligentsia admired Glinka’s technique and the opera’s apparent Russianness

Glinka’s compositions alluded to Russian folk and popular song

They also reflected “Romance” influence

These musical aspects made the fresh compositions seem familiar to Russian audiences

Non-Russian audiences, by contrast, noticed the

Italianate elements of the opera

Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842)

Glinka based his second opera on a narrative poem by Alexander Pushkin

(1799-1837)

Many considered Pushkin Russia’s greatest

19th-century poet

Unfortunately, he died before he could create a libretto for Glinka

The resulting libretto received a great deal of criticism

The fairy-tale opera emphasizes musical color over drama

Thus, the five acts pass very slowly

In this work, Glinka continued to experiment with the use of color to depict nationality

A quoted Finnish song characterized Finn, a kindhearted sorcerer

Glinka used many Orientalist devices to represent Ratmir, Lyudmila’s Eastern suitor

Remember, Glinka composed this opera before Orientalist clichés developed

The evil dwarf Chernomor received special musical treatment

This supernatural creature possessed a beard seven times his height

Glinka invented the whole-tone scale to depict

Chernomor’s magical existence

This scale divides the octave into six equal parts instead of eight

It moves in whole steps only

Glinka also called this scale his “chemical” scale

The whole-tone scale put off conventional rules of tonal harmony

This effect evoked a sense of the supernatural

Use of this scale indicated that human laws did not apply to the magical creature

The public did not react enthusiastically to the

1842 premiere of Ruslan and Lyudmila

Performances discontinued shortly after the premiere

Glinka’s popularity plummeted from the high point reached with A Life for the Tsar

Glinka considered this failure his greatest disappointment

As a result of his letdown, Glinka traveled abroad extensively

In Spain, Glinka took folk dancing lessons

His experiences inspired the orchestral pieces Jota

Aragonesa (1845) and Night in Madrid (1848)

In the end, Glinka returned to Russian styles in

Kamarinskaya (1848)

This orchestral work almost reconceived variation form

Glinka’s legacy and musical contributions

Russian composers mythologized Glinka and his contributions after his death

They took his example as the foundation for a new markedly Russian compositional style

His uncommon musical devices became part of

Russian national heritage

Some of these techniques came from Russian folk music

Others, however, simply arose from Glinka’s own creativity

Glinka championed the creation of folk-like musical idioms

He believed art music could benefit from elements of folk songs and dances

Only some of his folk melodies appeared as direct quotations

Glinka imitated folk music in his original material

He reproduced protyazhnayas and dance songs alike

Glinka also cleverly reproduced folk heterophony

He never lived with peasants or used audio technology

Thus, he worked with limited understanding of the texture

A Life for the Tsar demonstrates the composer’s affinity for folk-like sounds

The introductory chorus switches between a solo singer and the chorus

Glinka varied the number of individual voices present in the choral texture

Like folk music, he wrote two or three parts that converged to a unison

Glinka also employed the folk device peremennost’

This technique involved shifting between several equally important modal centers

Unlike most Western music at the time, folk tunes did not center on one tonic

Glinka’s chord progressions reflected this influence

However, he still used standard harmonies

Usually, Glinka moved between pairs of relative major and minor scales

The widespread use of 5/4 meter began with

Glinka

This unusual meter appears in the wedding choruses of both A Life and Ruslan

Indirectly, this device reflects folk influence

Russian folk poetry featured five-syllable lines that accented the third syllable

This characteristic frequently appeared in wedding songs

Russian folk song typically uses five notes of different length for the five syllables

Glinka, however, used five equal quarter notes

Glinka’s disciples treated 5/4 as an authentic

Russian meter

They also experimented with other uncommon meters

Borodin employed 7/4

Rimsky-Korsakov used 11/4

The whole-tone scale from Ruslan inspired other innovative scales

Rimsky-Korsakov created the octatonic scale

This scale alternates whole steps and half steps

It spans eight notes, hence the term “octatonic”

Rimsky-Korsakov’s invention proved more useful than the whole-tone scale

20th-century classical and jazz music incorporated the octatonic scale

Glinka’s fans also divided their works into sections with different musical rules

The composer also popularized “changing-background variations”

In fact, Russian scholars refer to this technique as “Glinka variations”

Typical variation form changes the melody while the accompaniment remains constant

Glinka variations do the exact opposite

The melody remains unchanged

All other elements (harmony, instrumentation, etc.) vary

Despite the deceptive name, Glinka did not originate the

Glinka variations

Beethoven uses this technique in “Ode to Joy” from his Ninth

Symphony

Movement 3 from Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 59 No. 2 also features this device

In fact, it centers on a Russian melody

Possibly, this earlier work inspired Glinka

Regardless of the technique’s origin, Glinka created important examples

For instance, he used folk themes with changing-background variations

This musical technique honored the folk melody

Glinka’s use of different musical colors for different nationalities in opera inspired others

This same principle also appeared in the West

There, composers referred to the technique as couleur locale

Glinka’s supporters focused on two operatic genres

They wrote heroic national dramas like A Life for the Tsar

Also, they composed fairytales like Ruslan and

Lyudmila

Glinka’s orchestral works also influenced subsequent composers

He never wrote any symphonies, only singlemovement overtures and fantasies

Other composers wrote on Russian and non-Russian folk themes

Balakirev composed the Czech Overture

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote the Serbian Fantasy

Glinka’s Kamarinskaya served as a model for future composers

This piece features Glinka variations on two themes

Similarly, Balakirev wrote Overture on Three Russian

Themes

Balakirev also composed the piano piece Islamey

The composer Lyapunov created the virtuosic

Lezghinka Etude for piano

Track 4: Kamarinskaya

Background

The single-movement Kamarinskaya involves a slow theme and a fast theme

Glinka alternates between variations on the slow and fast themes

The Russian wedding song “From behind Tall Hills” forms the slow theme

This theme occurs four times in different registers

Each repetition features different texture

The fourth statement appears in the bass line

“Kamarinskaya” refers to the sprightly dance tune that makes up the fast theme

This melody also lends its name to the piece as a whole

Folk tradition repeated this theme in “dancetill-you drop” variations

The piece’s form defies any previously established musical form

Instead, Glinka reinvents the variation form

His techniques elevate the folk melodies and variations

The excerpt on the USAD CD begins with the first fast section

The first violin section presents the opening statement of the theme

Glinka then adds other instrumental voices to the mix

Throughout the variations, Glinka barely alters the melody

When he does, the alterations suggest virtuosic fiddling

Each phrase sounds like an ostinato pattern

The 11th statement modulates from major to minor

Glinka emphasizes the opening notes of the slow theme

The slow theme reappears for two-and-ahalf statements

Then, the kamarinskaya dance tune resumes

At one point, Glinka drops the melody altogether, leaving only the accompaniment

The tempo slows down slightly as Glinka explores truly innovative variations

A C-natural in the horn produces dissonance against a D-major harmony

In the end, the tempo quickens triumphantly

The Mighty Handful and

“National” Style

The birth of Russian music conservatories

The Rubinstein brothers vastly enhanced musical education in Russia

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein rose to fame as one of the world’s top virtuoso pianists

He also worked as a conductor and composer

Anton’s younger brother Nikolai also performed as a pianist and conductor

A Russian border-guard stopped Anton as he returned from a European concert tour

Asked for his occupation, Anton replied that he was a “selfemployed artist”

The guard did not recognize this profession

Anton only received entry for being “the son of a merchant of the second rank”

This incident inspired Anton to work to improve the status of

Russian musicians

Between 1859 and 1860, the Rubinstein brothers formed the Russian Music Society

This institution organized a series of public concerts in St. Petersburg and Moscow

Anton worked in St. Petersburg while his brother lived in Moscow

The repertoire featured major works by the likes of Beethoven, Schumann, and Mendelssohn

For the first time in Russian history, the general population could access art music

Previously, a handful of aristocratic enthusiasts shaped most Russian musical life

The Rubinsteins also founded music conservatories in the two major cities

The St. Petersburg Conservatory opened in

1862 and the Moscow Conservatory in 1866

Musicians and composers no longer needed to enroll in private classes

Instead, these conservatories offered comprehensive five-year courses

Most professors came from abroad, especially from Germany

The conservatories increased the social prestige of musical careers in Russia

Russia now entered the wider world of international art music

Conservatories Vs. Mighty Handful

The Mighty Handful led an anticonservatory movement in Russia

These composers argued against conservatoriesdue to nationalistic concerns

They feared the institutions would overly

Westernize Russian music

Conservatories, they claimed, revealed too much foreign influence

Formation of the Mighty Handful

Vladimir Stasov (1824-1906) and Mily Balakirev

(1837-1910) became friends in the mid-1850s

Both men loved the music world

Balakirev performed as a pianist

He also composed his own pieces

Glinka personally encouraged Balakirev to continue composing

Stasov worked as a prominent music critic

Both dreamed of a distinctive Russian style of music

This style should appeal to both domestic and international listeners

Stasov and Balakirev hoped it would sound original and progressive

Balakirev and Stasov assembled four other musicians who shared this goal

Stasov first referred to the group as the moguchaya kuchka

Literally, this name translates to “the mighty little heap”

“Handful” sounds more elegant than the original

Russian term

In English, some refer to the group as “The Five” in reference to the five composers

However, this term overlooks the sixth important member, Stasov

Stasov alone of the Mighty Handful did not compose his own works

Nonetheless, he helped establish the group’s nationalist ideology

As a critic, he also promoted the group’s music and discredited rivals

Balakirev served as the Mighty Handful’s musical mentor

He was the only full-time musician in the group

At the time, composers struggled to maintain a living

Balakirev earned the majority of his income by teaching piano lessons

He still lived in relative poverty

The opera-loving Cesar Cui worked as an engineer building military fortifications

Army officer Modest Mussorgsky played the piano skillfully

However, he only composed polkas for aristocratic ladies

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov composed between tours of duty as a naval officer

Alexander Borodin served as an internationally acclaimed chemistry professor

He played the cello in his spare time

Despite their talent, the four lacked knowledge of technique and important repertory

Balakirev taught them the devices needed for large-scale works

He also introduced them to the masterworks of famous composers

Balakirev approached teaching differently than the conservatories

Of course, Balakirev stood firmly opposed to the conservatories

He favored a demanding but informal approach

Unlike conservatories, he did not assign exercises or “pastiche” composition

Instead, Balakirev played arrangements of symphonies on the piano

Mussorgsky, the skilled pianist, often joined him in duets

Balakirev then pointed out interesting forms, features and techniques

Balakirev sometimes created his own terms to explain music theory

Balakirev did assign ambitious homework projects, though

He instructed Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov to write a symphony

The task required a good amount of help and advice, according to letters

Mussorgsky and Cui attempted to write operas

Despite his stringent expectations, Balakirev also proved incredibly kindhearted

He himself composed passages that seemed beyond the skill of his students

When the scores were published, Balakirev did not claim credit

In the end, Balakirev’s pupils surpassed him in terms of fame

He selflessly devoted his attention to cultivating the group’s skill and creativity

Thus, he did not spend enough time on his own works

Completed late in his career, his works did not receive great recognition

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade features arabesque100 patterns in solo violin

A similar device appears in the solo clarinet from Balakirev’s Tamara

Balakirev’s work probably inspired Rimsky-

Korsakov’s

However, Scheherazade’s greater popularity leads listeners to believe the opposite

Creating “Russian style”

Balakirev and Stasov aimed to create the image of a unified “musical party”

Cui also proved instrumental in molding the

Handful’s public image

His writings saw publication in both Russia and France

The group worked in close cooperation in the

1860s

The composers wrote their first large-scale works collectively

Balakirev believed the compositional process should involve the entire group’s input

At first, the composers all pursued similar ideals

In later years, however, their ideas diverged considerably

To create “Russianness,” Balakirev mainly advocated avoidance of Western clichés

Balakirev used pieces by some Western composers as negative examples for his pupils

Felix Mendelssohn’s works allegedly represented Germanic “routine”

Balakirev hated the smooth musical periods characteristic of these pieces

Balakirev also disparaged the overly sentimental compositions of Frederic Chopin

However, Balakirev did approve of

“progressive,” original Western composers

Balakirev championed the works of Ludwig van

Beethoven and Robert Schumann

He admired these composers’ use of strong rhythmic motives

Moreover, he liked their compelling experiments with form

Franz Liszt and Hector Berlioz also met with

Balakirev’s approval

These composers skillfully wrote “program music”

Their compositions used musical colors to depict characters and events

In addition to these Western composers,

Balakirev also promoted Glinka’s works

Above all else, Balakirev stressed the importance of originality in composition

“Russianness” would result from avoidance of

Western devices

For instance, he instructed his students to avoid common harmonic progressions

He considered the IV-V-I cadence too clichéd

Instead, he suggested skipping the dominant

(V), creating a IV-I cadence

Otherwise, the composers might disguise the dominant chord

Balakirev also taught his students to incorporate folk and Oriental idioms

The Mighty Handful turned to folk song for non-Western material

Balakirev alone traveled through Russia to collect folk melodies

Most of the songs came from educated individuals, not the peasants themselves106

Still, Balakirev published 40 of these tunes in 1866

His collection included his own original piano accompaniments

The Mighty Handful seized this material for their own compositions

These accompaniment devices reflected

Balakirev’s tastes, not the original tunes

However, due to the Handful’s widespread use, many listeners mistakenly

The Caucasus region inspired the Handful to develop the Oriental style

Balakirev absorbed Georgian, Armenian, and

Turkic musical elements

¨ New melodic and instrumentation ideas shaped the Handful’s works

¨ These foreign devices helped distance the

Handful from Western composers

¨ Oriental music sounded instantly non-Western

¨ It proved more difficult to make folk music sound non-Western o Audiences reacted favorably to the Oriental style o Western listeners began to notice the Handful o For various reasons, they identified all Handful compositions as distinctly “Russian”

Many Russian composers incorporated the new

Oriental style in some of their works

Balakirev began the movement in the 1860s with his piece Islamey

Finished in 1869, this piano piece centers on a

Caucasian-inspired folk dance

Balakirev applied Glinka variations to the theme

Liszt’s virtuosic compositions also influenced

Balakirev’s piece

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote Antar (1868), a symphonic suite

The music depicted an Eastern fairy tale in

Oriental style

Borodin’s opera Prince Igor featured the

Orientalist Polovtsian Dances

Mussorgsky and Cui also experimented with

Oriental themes in opera

The Handful also turned to Glinka’s oeuvre

(composer’s lifetime works) for inspiration

Thanks to the Handful, listeners considered Glinka’s innovations innately

“Russian”

In particular, these composers favored the changing-background variations form

This device proved especially useful for pieces based on folk themes

Rimsky-Korsakov expanded on Glinka’s approach to the supernatural

His fairytale and supernatural works featured

Glinka’s whole-tone scale

Rimsky-Korsakov also invented the octatonic scale

This scale alternates half steps and whole steps

It contains eight pitches in an octave rather than the typical seven

Russian scholars call this device the “Rimsky-

Korsakov scale”

Today, jazz composers still use the scale

Like Glinka, Rimsky-Korsakov used his unique scale to suspend tonal rules

This effect resulted in an unearthly, exotic sound

In Sadko, this scale represents the

Underwater Kingdom

Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Kashchei the

Deathless also features this scale

The Mighty Handful also embraced

Glinka’s use of unusual meters

They realized folk melodies did not easily conform to regular meters

Thus, they switched between measures of

2/4, 3/4, and 4/4

Besides Glinka’s trademark 5/4, his followers used 7/4 and 11/4

Second Symphony, Opening

Alexander Borodin composed this symphony

Russian musicians nicknamed the piece

Bogatyrskaya

o Borodin did not intend to create a truly programmatic piece

However, he thought the opening theme represented bogatyri, ancient Russian warriors

The striking opening begins with a unison line carried by the entire orchestra

The first movement repeats this first phrase several times

Each repetition sounds more grand

Borodin employs augmentation, lengthening the note values of the phrase

Two keys shape the opening section

It starts out in B minor, though the first phrase contains two chromatic pitches

The repetition of the phrase modulates to D major

The piece continues to hover between these two closely related keys

Unlike German symphonic allegros, the symphony does not establish one main key

The uncertainty of the key vaguely reflects the folk technique of peremennost’

In peremennost’, a piece shifts between two modal centers

Unlike Western music, no single tonic defines the key of the piece