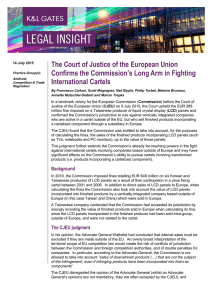

Case Study 6.2

advertisement

Case Study 6.2: The EU and the Liquid Crystal Displays case. In December 2010, the Commission fined six Liquid Crystal Displays (LCD) panel producers a total of €648 million for operating a price fixing cartel between October 2001 and February 2006. LCD panels are the main component of thin, flat screens used in televisions, computer monitors and electronic notebooks. The six were Samsung Electronics and LG Display of Korea and Taiwanese firms AU Optronics, Chimei InnoLux Corporation, Chungahwa Picture Tubes and HannStar Display Corporation. These suppliers are global players, with the cartel meeting about 65-80% of world demand for large size LCD panels during the period of the infringement. This, of course, meant that the cartel would not just be of interest to the Commission, but also to other regulators including the US Department of Justice and China’s National Development and Reform Commission. During the above mentioned period, the Commission found that the cartel agreed prices, including price ranges, exchanged information on future production planning, capacity utilisation, pricing and other commercial conditions. The Commission further found that the cartel’s multilateral ‘crystal meetings’ took place at least monthly, normally in a hotel in Taiwan, for the purpose of not only entering into anti-competitive practices but also to ensure compliance with the arrangements previously entered into – the cartel took the possibility of cheating by one or more of its members very seriously. This led the Commission to conclude that these meetings had a direct impact on EU customers because the vast majority of televisions, computer monitors and notebooks incorporating the said LCD panels and sold in the SEM came from Asia. As these are non-EU companies, the Commission felt it necessary to explain the basis on which they could be vetted under EU competition law, specifically Article 101 TFEU. The Commission asserted jurisdiction based on the Community courts’ Wood pulp and Gencor rulings (see above). The Commission declared that, based on the CJEU’s ruling in Wood pulp, the decisive factor in the determination of the applicability of Article 101 TFEU in cases where the participants of a cartel are seated outside the Community is whether the agreement, decision or concerted practice was implemented within the EU. The Commission further added that the GC in its Gencor ruling had established that EU competition law is applicable if the conduct at issue has immediate, foreseeable and substantial effect in the Community – the so-called effects doctrine. However, the Commission’s jurisdiction in the case was challenged by some members of the cartel, arguing that the Commission had not demonstrated that the implementation criterion or the effects doctrine had been satisfied. The Chimei InnoLux Corporation asserted that the Commission had failed to apply the implementation test deriving from the Wood pulp ruling, and that the effects doctrine’s conditions would not be met as no direct, foreseeable and substantial effects were shown in the Commission’s statement of objections. Similarly, LG Display argued that the Commission’s statement of objections did not clearly show that the implementation criterion or the effects doctrine had been satisfied. The enterprise further claimed that the characteristics of the market in question showed that that the agreement was not and could not be implemented in the EU. AU Optronics contended that the Commission should have established that the alleged agreement had an effect on sales to direct customers within the EU and that those effects were substantial, immediate and foreseeable. It further submitted that the Commission, under the principle of international comity, is required to refrain from applying domestic laws when so doing would impinge on the territorial sovereignty of another state. In a similar vein, LG Display contended that the Commission should apply the international legal principle of comity, including the co-operation agreement with S Korea concerning co-operation on anti-competitive activities. In other words, the Commission should consult with other regulatory authorities to determine whether it was the best placed authority to investigate the case. The above forced the Commission to apply both the implementation criterion and the effects doctrine so as to establish its jurisdiction in the case. Concerning the former, the Commission asserted that contemporaneous evidence revealed that in addition to explicitly discussing some of their main customers in Europe, the parties were analysing and referring to the effects of the implemented agreement on the European market and therefore sought their agreement to be implemented and have effects within the European Economic Area (EEA). Concerning the latter, the Commission declared that, based on the sale of the LCD panels to the EEA in the form of direct EEA sales and direct EEA sales through transformed products, it can be established that the infringement had immediate, foreseeable and substantial effect in the Community in the sense of the Gencor case law. In relation to the three conditions, the Commission concluded that the infringement immediately affected EEA markets since the agreements and concerted practices directly influenced the setting of price for LCD panels delivered directly or through transformed products to European customers. Secondly, that the effect on the European market was foreseeable as the price rise or the maintenance of higher prices and the reduction of output were to have evident consequences on the conditions of competition at the downstream level for all IT and television applications. Finally, that the effect of the agreement was deemed to be substantial due to the seriousness of the infringement, its long duration and the impact of the parties on the European market for the said final and intermediate products. In relation to the arguments of AU Optronics and LG Display concerning the principle of international comity, the Commission asserted that it was not in breach of this and nor was this the case in respect of its competition co-operation agreement with Korea. Indeed, in line with this agreement, the Commission had consulted with the Korean competition authority and the latter did not claim that any important interests mentioned in Article 5 of the agreement was affected. Moreover, the Commission pointed out that both the OECD Recommendations on Anti-Competitive Practices Affecting International Trade and the EU-Korea competition co-operation agreement allowed a competition authority full freedom to adopt decisions in competition cases within their own jurisdiction. Having established jurisdiction, the Commission duly found the cartel to have breached Article 101 TFEU, with the next step being to determine the fine for each member. In deciding the amount of the fine, the Commission must take stock of the gravity and duration of the infringement, with the upper limit being set at 10% of total turnover for the previous business year for the fined enterprise. In the LCD case, Samsung Electronics received full impunity from being fined under the Commission’s 2002 leniency programme, as the enterprise brought the cartel to the Commission’s notice and provided valuable information to prove the infringement. Likewise, some other members of the cartel saw a percentage reduction in their fine, though this varied from enterprise to enterprise, according to the co-operation they provided to the Commission. However, Chimei InoLux Corporation and HannStar Display Corporation received no such reduction and were accordingly fined €300 million and just over €8 million respectively. Of course, this was not necessarily the end of the financial cost to the members of the cartel because they could also face claims for damages. Indeed, the Commission’s LCD press release pointed out that any person or enterprise affected by ant-competitive behaviour as described in the LCD case can seek damages. It further informed that, even though the Commission has fined the companies concerned, damages may still be awarded without these being reduced on account of the Commission fine. Case questions 1. Explain why the LCD agreement breached EU competition law? 2. Given that the six companies in the agreement were Asian, on what grounds did the Commission claim legal jurisdiction in the case? 3. Assess the view that the LCD decision represents a further success story for the Commission’s leniency programme? 4. Why might private enforcement now be a realistic possibility in these types of anti-competitive infringements?