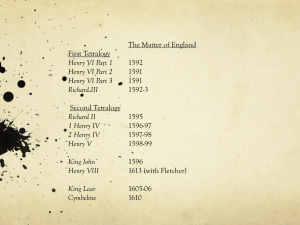

1, 2 Henry IV and Henry V

advertisement

1, 2 Henry IV Honor Hotspur (1.3.201): By Heaven, methinks it were an easy leap, To pluck bright honour from the pale-faced Moon; Or dive into the bottom of the deep, Where fathom-line could never touch the ground, And pluck up drowned honour by the locks; So he that doth redeem her thence might wear Without corrival all her dignities: But out upon this half-faced fellowship! Honor Falstaff (5.1.128) Well, 'tis no matter; honour pricks me on. Yea, but how if honour prick me off when I come on? how then? Can honor set-to a leg? no: or an arm? no: or take away the grief of a wound? no. Honour hath no skill in surgery then? no. What is honour? a word. What is that word, honour? air. A trim reckoning!—Who hath it? he that died o' Wednesday. Doth he feel it? no. Doth be hear it? no. Is it insensible, then? yea, to the dead. But will it not live with the living? no. Why? detraction will not suffer it. Therefore I'll none of it: honour is a mere scutcheon:—and so ends my catechism. Imitation of Hotspur Hotspur (2.3.45) KATE: Some heavy business hath my lord in hand, And I must know it, else he loves me not. HOT.: What, ho! [Enter a Servant.] Is Gilliams with the packet gone? SERV.: He is, my lord, an hour ago. HOT.: Hath Butler brought those horses from the sheriff? Imitation of Hotspur PRINCE: What's o'clock, Francis? FRAN.: [Within.] Anon, anon, sir. PRINCE.: That ever this fellow should have fewer words than a parrot, and yet the son of a woman! His industry is up-stairs and down-stairs; his eloquence the parcel of a reckoning. // I am not yet of Percy's mind, the Hotspur of the North; he that kills me some six or seven dozen of Scots at a breakfast, washes his hands, and says to his wife, Fie upon this quiet life! I want work. O my sweet Harry, says she, how many hast thou kill'd to-day? Give my roan horse a drench, says he; and answers, Some fourteen, an hour after,—a trifle, a trifle. I pr'ythee, call in Falstaff: I'll play Percy, and that damn'd brawn shall play Dame Mortimer his wife. Henry IV’s disgust with Hal Henry (Richard II 5.3.1 ff): Can no man tell me of my unthifty son? ‘Tis full three months since I did see him last. If any plague hang over us, ‘tis he. I would to God, my lords, he might be found. Inquire at London, ‘mongst the taverns there, For there, they say, he daily doth frequent, With unrestrained loose companions, Even such, they say, as stand in narrow lands And beat our watch and rob our passengers, Which he, young wanton and effeminate boy, Takes on the point of honor to support So dissolute a crew. Henry IV’s disgust with Hal KING (1.1.80).: Yea, there thou makest me sad, and makest me sin In envy that my Lord Northumberland Should be the father to so blest a son,— A son who is the theme of honour's tongue; Amongst a grove, the very straightest plant; Who is sweet Fortune's minion and her pride: Whilst I, by looking on the praise of him, See riot and dishonour stain the brow Of my young Harry. O, that it could be proved That some night-tripping fairy had exchanged In cradle-clothes our children where they lay, And call'd mine Percy, his Plantagenet! Then would I have his Harry, and he mine: Henry IV’s disgust with Hal imitated FAL.: Peace, good pint-pot; peace, good tickle-brain.—Harry, I do not only marvel where thou spendest thy time, but also how thou art accompanied: for though the camomile, the more it is trodden on, the faster it grows, yet youth, the more it is wasted, the sooner it wears. . . . There is a thing, Harry, which thou hast often heard of, and it is known to many in our land by the name of pitch: this pitch, as ancient writers do report, doth defile; so doth the company thou keepest: for, Harry, now I do not speak to thee in drink, but in tears; not in pleasure, but in passion; not in words only, but in woes also. Euphuism A literary style popular found in John Lyly’s Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578), consisting in “unnatural natural history” (the camomile, pitch), and balanced, rhyming phrases. “This young gallant, of more wit than wealth, and yet of more wealth than wisdom, seeing himself inferior to none in pleasant conceipts, though himself inferior to none in pleasant conditions.” “One drop of poison infecteth the whole run of wine one leaf of colliquintida marreth and spoileth the whole pot of porridge, one iron mole defaceth the whole piece of lawn [fabric].” “The spider weaveth a fine web to hang the fly, the wolf weareth a fair face to devour the lamb, the merline striketh at the patridge, and the eagle often snappeth at the fly, men are always laying baits for women, which are the weaker vessels; but as yet I could never hear man by such snares to intrap man.” “I would it were in Naples a law, which was a custom in Egypt, that women should always go barefoot, to the intent they might keep themselves always at home, that they should be ever like the snail which hath ever his house on his head.” Henry IV’s disgust with Hal PRINCE (2.4.430).: Swearest thou, ungracious boy? henceforth ne'er look on me. Thou art violently carried away from grace: there is a devil haunts thee, in the likeness of an old fat man,—a tun of man is thy companion. Why dost thou converse with that trunk of humours, that bolting-hutch of beastliness, that swollen parcel of dropsies, that huge bombard of sack, that roasted Manningtree ox with the pudding in his belly, that reverend Vice, that grey Iniquity, that father ruffian, that vanity in years? Wherein is he good, but to taste sack and drink it? wherein neat and cleanly, but to carve a capon and eat it? wherein cunning, but in craft? wherein crafty, but in villany? wherein villainous, but in all things? wherein worthy, but in nothing? Henry IV’s disgust with Hal KING (3.2.95): For all the world, As thou art to this hour, was Richard then When I from France set foot at Ravenspurg; And even as I was then is Percy now. ... Thrice hath this Hotspur, Mars in swathing-clothes, This infant warrior, in his enterprises Discomfited great Douglas; ta'en him once, Enlarged him, and made a friend of him, .... Why, Harry, do I tell thee of my foes, Which art my near'st and dearest enemy? Thou that art like enough, . . . To fight against me under Percy's pay, To dog his heels, and curtsy at his frowns, To show how much thou art degenerate. Henry IV’s disgust with Hal KING (2 Henry IV 4.3.239 ff. after Hal, thinking his father has died, puts on his crown, then finds him alive): What, canst thou not forbear me half an hour? Then get thee gone, and dig my grave thyself, And bid the merry bells ring to thine ear That thou art crownèd, not that I am dead. ... Now neighbor confines, purge you of your scum! Have you a ruffian that will swear, drink, dance, Revel the night, rob, murder, and commit The oldest sins the newest kind of ways? Genre: History has an element of tragedy In Romeo and Juliet, where a medicinal flower can also be poison, and one’s best intentions can bring on the worst consequences, so is the crown. Here the crown seems precious but can prove poisonous: Prince Henry (2 Henry IV 4.3.290): Coming to look on you, thinking you dead, And dead almost, my liege, to think you were, I spoke unto this crown as having sense, And thus upbraided it, “The care on thee depending Hath fed upon the body of my father; Therefore thou best of gold are worse than gold. Other, less fine in carat, is more precious, Preserving life in medicine potable; But thou, most fine, most honoured, most renowned, Hath eat thy bearer up.” Past injuries Garden imagery, often related to the political situation in England Hotspur (1.3.170): Shall it, for shame, be spoken in these days, Or fill up chronicles in time to come, That men of your nobility and power Did gage them both in an unjust behalf,— As both of you, God pardon it! have done,— To put down Richard, that sweet lovely rose, And plant this thorn, this canker, Bolingbroke? Falstaff (2.4.293) Shall the blessed Sun of heaven prove a micher, and eat blackberries? a question not to be ask'd. Shall the son of England prove a thief, and take purses? a question to be ask'd. Falstaff’s unfitness FALSTAFF (4.2.60 If I be not ashamed of my soldiers, I am a soused gurnet. I have misused the King's press damnably. I have got, in exchange of a hundred and fifty soldiers, three hundred and odd pounds. I press'd me none but good householders, yeomen's sons; . . . I press'd me none but such toasts-and-butter, with hearts in their bodies no bigger than pins'-heads, and they have bought out their services; and now my whole charge consists of ancients, corporals, lieutenants, gentlemen of companies, slaves as ragged as Lazarus in the painted cloth, where the glutton's dogs licked his sores; and such as, indeed, were never soldiers, but discarded unjust serving-men, younger sons to younger brothers, revolted tapsters, and ostlers trade-fallen; the cankers of a calm world and a long peace. PRINCE (4.2.61 ff.).: I did never see such pitiful rascals. FAL.: Tut, tut; good enough to toss; food for powder, food for powder; they'll fill a pit as well as better: tush, man, mortal men, mortal men. Compare 2 Henry IV act 3, scene 2, where we actually see Falstaff take bribes. Genre: Comedy Some elements of comedy. See list at end of MSND notes. Word play, creation of social harmony, overcoming death, hints of heaven (sun and son and the king’s relation to God’s justice). Genre of History History tells us what happened, not what should have happened. Patriotic, sentimental but also serious recreations of real events with added episodes for audience appeal. Like Westerns, leading up to a final duel or battle, often with a sense of loss for a simpler past. But the history plays are not real comedies or tragedies. Falstaff is not really dead, only faking, and the moral decisions which give tragedy its peculiar effect are missing: We imagine that Hotspur, had he to do everything over again, might have taken the king’s offer. Genre of History History involves a story. Christian Humanists saw history as the working out of a divine purpose or providence. But history also showed how human will could overcome Fortune, as Machiavelli recommended. Subversion and Containment “Who does not all along see,” wrote Upton in the mid-eighteenth century, “that when prince Henry comes to be king he will assume a character suitable to his dignity?” My point is not to dispute this interpretation of the prince, as in Maynard Mack’s wods, “an ideal image of the potentialities of the English character,” but to observe that such an ideal image involves as its positive condition the constant production of its own radical subversion and the powerful containment of that subversion. (Stephen Greenblatt, “Invisible Bullets,” in Shakespearean Negotiations [Berkeley: U of California P, 1988], 41). Edward Hall, The Union of Two Noble and Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York Raphael Holinshed, The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland Owen Glendower came from “the county of Merioneth in North Wales, in a place called Glindourwie, which is as much to say in English, as The valley by the side of the water of Dee. He was first set to study the law of the realm.” When Henry fought him “Owe conveyed himself out of the way, into his known lurking places, and (as was thought) through art magic, he caused such foul weather of winds, tempest, rain, snow, and hail to be raised for the anoyance of the King’s army, that the like had not been heard of” Raphael Holinshed, The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland “Henry, Earl of Northumberland, with his brother Thomas, Earl of Worcester, and his son the Lord Henry Percy, surnamed Hotspur, which were to King Henry in the beginning of his reign, both faithful friends, and earnest aiders, began now to envy his welath and felicity; and especially they were grieved, because the King demanded of the Earl and his son such Scottish prisoners as were taken at Holmedon.” Raphael Holinshed, The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland “And to speak a truth, no marvel it was, if many envied the prosperous state of King Henry, since it was evident enough to the world, that he had with wrong usurped the crown, and not only violently deposed King Richard, but also cruelly procured his death; for th ewhich undoubtedly, both he and his posterity tasted such troubles, as put them still in danger of their states.” An Homily Against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion (1571) That year seven-year old Shakespeare would have seen soldiers marched through Stratford to put down the Northern Rebellion of the Percies, fighting for Mary, Queen of Scots. Church attendance was obligatory; Catholics and Protestant dissenters to the Church of England (Elizabeth’s way of uniting the country without looking into people’s private spiritual believs) could be fined. Governors are God’s deputies on earth: Romans 13: “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers, for there is no power but of God, and the powers that be, are ordained of God.” (Paul’s letters are the mainstay of Protestantism.) The location of the theaters just outside London reflected in the alternation of royal and tavern scenes Putting on representations of monarchy, modern critics argue, strips away their sacred aura. Or it gives voice to political dissonance only to contain it, as Stephen Greenblatt argues in “Invisible Bullets.” Taverns and women In England, in contrast to many other countries, women frequented alehouses and the theater. There was also regulated prostitution in London. Social classes, from William Harrison’s The Description of England The greatest sort are princes, dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts, and barons; below them are knights, esquiers, and gentlemen. “Knights be not borne, neither is any man a knight by succession . . . but they are made either before the battle, to encourage them the more to adventure & try their manhood; or after the battle. . . . His wife is by and by called madame or lady. Gentleman are so from their race and blood “or at the least their virtues do make [them] noble and known.” “Citizens and burgesses have next place to gentlemen, who be those that are free with the cities, and are of somme likely substance to bear office the same. . . [In the counties] they bear but little sway” [or in Parliament, where the law are made]. (Cf. modern America, where 15% of the population controls over 50% of the Senate.) Social classes, from William Harrison’s The Description of England “Yeomen [are] free born English, and may dispend of their own free land in yearly revenue, to the sum of forty shillings sterling. . . . They are for the most part farmers to gentlemen. “The fourth and last sort of people in England are day labourers . . . and all artificers, such as tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, brick makers, masons, etc. . . As for slaves and bondmen we have none, such is the privilege of our country by the especially grace of God, and bounty of our princes, that is any come hither from other realms, so soon as they set foot on land they become so free of condition as their masters, whereby all note of servile bondage is utterly removed from them.” John Stow, A Survey of London (1603) “Now to return to the West bank, there be two Bear gardens. . . Next on this bank was sometime the Bordello or stews, a place so called of certain stew houses privileged there, for the repair of incontinent men to the like women.” Under Henry II this law was passed, That no stewholder or his wife should let or stay any single Woman to go and come freely at all times. No stewholder to keep any woman to board, but she to board abroad at her pleasure. No single woman to be kept against her will that would leave her sin. No single woman to take money to lie with any man, but she lie with himmall night till the morrow. The Constables, Bailiff, and others every week to search every stewhouse. No stewholder to keep any woman that hath the perilous infirmity of burning, nor to sell bread, ale, flesh, fish, wood, coal, or any victuals. Key passages in 1 Henry IV 1.2.1 Poins and Hal in the royal apartments (compare to 2 HIV 2.2, where Poins has to admit he curries favor with Hal, wants him to marry his sister) 1.2.186: Hal imitates the sun (son/sun) 1.3.93: Hotspur describes Mortimer’s duel with Glendower 1.3.110: Hotspur describes effeminate lord 1.3.188: Worcester’s “secret book” 1.3.240: Hotspur gropes for “Ravensburgh” Key passages in 1H4 2.1.18: the jordan (cf. Falstaff’s water at 2H4 1.2.1 and 2.4.35) 2.1.30: Gadshill asks for time, lantern 2.1.43: Chamberlain appears as if in a pantomime 2.1.68: other Trojans 2.2.29: “lie down” 2.2.80: “us youth” 2.2.99: counter-robbery 1H4 tavern scene 2.4.1: Is Hal drunk?Compare him and the tapsters to Bottom and the flower fairies. One of the boys. 2.4.1: “Drawer stands amazed”--see Stephen Greenblatt, “Invisible Bullets,” from Shakespearean Negotiations (Chicago, 1988), 21-65. 2.4.89: Poins asks the point of the jest 2.4.99: break in the line; playful, not for honor 2.4.115: difficult line: Titan (Falstaff) melts butter (drinks sack), busying himself, blaming Francis for lime, so as not to directly accuse Hal of cowardice (knowing he himself was the coward). 2.4.188: “my old ward” 2.4.229: “compulsion” 2.4.254: Hal reveals the truth 2.4.261: Falstaff counters with “instinct” 2.4.337: The Douglas’s feats of horsemanship 2.4.388: review euphuism slide 2.4.534: money put back with interest 1H4 key passages 3.1.12-51: Glendower’s nativity, “front of heaven,” “vasty deep” 3.1.90: Hotspur’s “moiety” (cf. Pistol’s “moys” at Henry V 4.4.18): moiety = my share, which is how Pistol understand “moi,” which means “me” in French. (“Pourquoi,” asks silly Sir Andrew Agucheek in Twelfth Night, “Is that do or not do?”--wrong on both counts). 3.1.240: Hotspur mocks Kate’s mild oath (nasty, perhaps, but what other couple shows such affection in any play?) Falstaff: Repentance and debt Falstaff is known for finding the right word to escape from a lie (“vocation” “instinct”). He also owes money to Mistress Quickly. 3.3.70 and throughout. He also likes to say he will repent just before agreeing to the robbery in 1.2.93 (“I must give over this life”) and asking Bardolph for a bawdy song (“I’ll repent” 3.3.5)--question is, how many times can a character do the same routine for an audience? Queen Elizabeth herself is said to have asked for a play about Falstaff, hence The Merry Wives of Windsor. Key passages in 2 Henry IV 3.1.31: “Then happy low, lie down; / Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown” 4.2.267-306: Elements of tragedy, esp. 290-295: gold as poison and medicine 4.3.344: Henry recommends foreign quarrels (Holy Land, France) 5.1.69-75: Falstaff confesses his method: to amuse Hal. Compare 2.2.117-135, where Poins also has an interest in entertaining Hal. 5.3.90-120: Pistol, a humor character. 5.4.15: Doll and Pistol have killed a customer 5.5.45: “I know thee not” Key Passages in 2 Henry IV 1.ind.1-40: Rumor 1.1.1-48: Lord Bardolph’s good news v. Harry’s cold spur 1.2.1-243 (page hired by Prince, 12--compare 2.2.65; debt to Master Dommelton, 28; “security,” 36; Prince struck Lord Chief Justice (not shown), 53; king’s sickness (“apoplexy”), 105); Falstaff’s nativity, 181 (compare Glendower’s). Falstaff arrested for debt, 2H4 2.1 2.1.30: “my exion is entered, and my case so openly known to the world” [See Patricia Parker, Literary Fat Ladies (Routledge 1988) for the pun on “case”] Note where Mistress Quickly claims Falstaff promised to marry her (84 ff.), yet also offers to procure Doll Tearsheet for him (159). She is called a “road” at 2.2.158. For the “action” of the scene, see the scene by scene summary. Note also act two scene 4, which you should watch, as it shows Falstaff at the height of his powers. It parallels the 1H4’s tavern scene 2.4. Key passages in 2 Henry IV