Model Ordinance Regulating Sales of SSBs

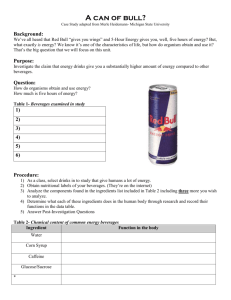

advertisement