Making the Most of LDC and Research-Based Ways

advertisement

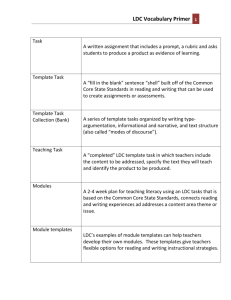

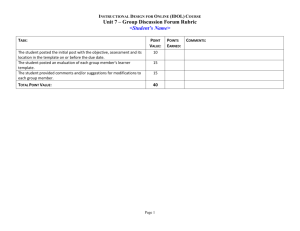

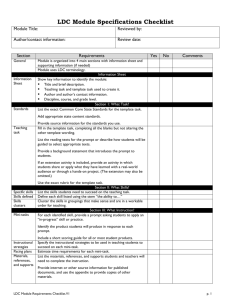

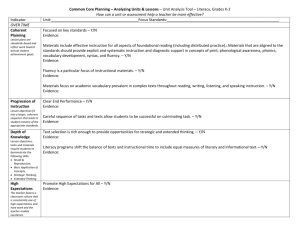

Target-based Writing Instruction: Making the Most of LDC and Research-Based Methods for Improving Student Writing Review of: --Writing Next (Graham & Perrin, 2007) The ultimate goal is to teach students to use these strategies independently. Reviewing and using standardized testing data Reviewing and using common assessment results Noting patterns of strength and need via classroom observation Noting patterns of strength and need via informal assessment of student writing We do not teach content and strategies because “This is the time we always teach X.” We do not teach content and strategies because “This is how I’ve always done it.” We teach content and strategies because we have professionally assessed that our students: A) Have need for particular instruction B) Are ready for particular instruction ▪ Note that this implies that instruction cannot and should not be “paced” or “leveled” or standardized across grade levels, classrooms, or even individual classes. ▪ Note that doing any of the above entails a direct violation of CHETL, which functions as state law regarding the required use of research-based instructional practices AT ALL TIMES. Creating extended opportunities for writing; Emphasizing writing for real audiences Encouraging cycles of planning, translating, and reviewing Stressing personal responsibility and ownership of writing projects Facilitating high levels of student interactions Developing supportive writing environments Encouraging self-reflection and evaluation Offering personalized individual assistance, brief instructional lessons to meet students’ individual needs, and, in some instances, more extended and systematic instruction. Facilitating high levels of student interactions Developing supportive writing environments Encouraging self-reflection and evaluation Offering personalized individual assistance, brief instructional lessons to meet students’ individual needs, and, in some instances, more extended and systematic instruction. Note that while “process writing” is represented here as having a lower effect size than some other strategies, nearly all of those other more powerful strategies are integrated into the process writing workshop model for writing instruction. That integration is why workshop and process writing are so widespread in U.S. classrooms. Explicitly strategies for Planning Drafting Revising Editing Extremely powerful in improving quality of writing for ALL students. Teach, Tell, Show, and Practice vs. Assign and Assume Generic processes: Brainstorming ▪ (e.g.,Troia &Graham, 2002) Collaboration for peer revising ▪ (MacArthur, Schwartz, & Graham, 1991). Strategies for accomplishing specific types of writing tasks: Writing a story ▪ (Fitzgerald &Markham, 1987) Writing a persuasive essay ▪ (Yeh, 1998) Setting product goals Specific, reachable goals for the writing they are to complete. ▪ Identifying the purpose of the assignment (e.g., to persuade) ▪ Identify the essential components and characteristics of a successful final product. Adding more ideas to a paper when revising, Establishing a goal to write a specific kind of paper Assigning goals for specific structural elements in a composition. Specific punctuation Types of sentence structures Use of vocabulary or terminology from content Focus on paragraph structure Spelling Planning before writing Organizing pre-writing ideas, prompting students to plan after providing a brief demonstration of how to do so Assigning reading material pertinent to a topic and then encouraging students to plan their work in advance. Inquiry means engaging students in activities that help them develop ideas and content for a particular writing task by analyzing immediate, concrete data (comparing and contrasting cases or collecting and evaluating evidence). E.g., Hillocks example of “blindfolded description”; “The Potato Activity” Brainstorming Listing Listing in response to questions Clustering/webbing Freewriting (pure) Freewriting (topic focused) Rehearsing (pair planning) Drawing (all ages!) Making maps (idea/detail generation) Visualization Idea prompts Compared with composing by hand, the effect of word-processing instruction in most of the studies reviewed was positive, suggesting that word processing has a consistently positive impact on writing quality. Note: May depend on the goals for writing. ▪ Writing to think may initially be more successful via handwriting. Explicitly and systematically teaching students how to summarize texts. See Handout re: “How to Write a Systematic Summary” Distinguish between “summary” and “paraphrase” Collaborative arrangements in which students help each other with one or more aspects of their writing have a strong positive impact on quality. Collaborative Structures: Writing Partners Peer Editing Writing Groups “Publisher’s Chair” Peer Conferencing The study of models provides adolescents with good models for each type of writing that is the focus of instruction. Combining smaller related sentences into a compound sentence using the connectors and, but, and because; Embedding an adjective or adverb from one sentence into another Creating complex sentences by embedding an adverbial and adjectival clause from one sentence into another Making multiple embeddings involving adjectives, adverbs, adverbial clauses, and adjectival clauses. The meta-analysis found an effect for this type of instruction for students across the full range of ability, but surprisingly, this effect was negative. This negative effect was small, but it was statistically significant, indicating that traditional grammar instruction is unlikely to help improve the quality of students’ writing. LDC template tasks are “shells” of assignments that ask students to read, write, and think about important academic content in science, social studies, English, or another subject. Teachers fill in those shells, deciding the texts students will read, the writing students will produce, and the content students will engage. [Insert essential question] After reading ___________ (literature or informational texts), write an ________ (essay or substitute) that addresses the question and support your position with evidence from the text(s). L2 Be sure to acknowledge competing views. L3 Give examples from past or current events or issues to illustrate and clarify your position. LDC design team, Template Task Bank Teachers fill in the prompt, including: The content of the task Texts to read Text students will write Whether to use the L2 and L3 options to make the task more demanding Teachers also decide on: What background information about the teaching task should be shared with students Which state or local standards the teaching task will address Whether and how to use an extension activity (Writing Process formative tasks) with the teaching task Template tasks come with rubrics for scoring students’ work and specifications of the Common Core State Standards the resulting tasks will address. Some template tasks provide optional additions to the basic assignment, allowing teachers an additional way to vary the level of work students will create. All rich instruction allows us to teach all ELA elements. That’s impossible for you and your students. Choose 1-2 specific targets per task/assignment ▪ ONLY GRADE THE TARGETED ELEMENTS ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ Saves you time Enables clearer, focuses data analysis Lightens students’ cognitive loads Does NOT mean that “anything goes” or that “correctness” does not matter. Implementing the Writing Process via LDC Via the poem “Courage” by Anne Sexton Integrating research-based instructional strategies as explicit parts of the instructional and learning process. ▪ See Handouts re: “Courage” and “Strategy Use with Sexton”