Impact and Treatment of Opioid Dependence

advertisement

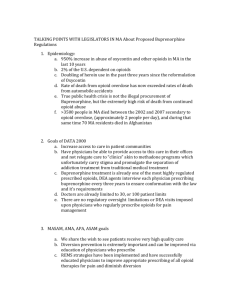

Impact and Treatment of Opioid Dependence Thomas E. Freese, PhD PI/Director, Pacific Southwest Addiction Technology Transfer Center Director of Training, UCLA Integrated Substance Abuse Programs Asst Research Psychologist, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine SPLENDID FOR Wind, Colic, Griping in the Bowels, Diarrhea Cholera and Teething Troubles Prevalence of Opioid Use and Abuse in the United States Rates of Current Heroin Use • Drug demand data show that, nationally, current heroin use is stable or decreasing. Rates of Past-Year Heroin Use – NSDUH, 2009 % of US population 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 0.1 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.2 Adolescents (12-17) 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.2 Adults (18-25) 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.4 0.4 0.5 Adults (26 & older) 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.3 Individuals (12 & older) (SAMHSA, 2009) Who Uses Heroin? Individuals of all ages use heroin: • More than 3.8 million US residents aged 12 and older have used heroin at least once in their lifetime. • Heroin use among high school students is a particular problem. Slightly more than 2% percent of US high school seniors used heroin at least once during their lifetime. • Approximately 1.6% of young adults (CDC, 2009; SAMHSA, 2007) reported lifetime use (ages 19-28) Prevalence of Use Rates of heroin use are declining among youth • 8th grade use peaked in 1996 • 10th grade use peaked in 1997 • 12th grade use peaked in 2000 Rates of non-medical use of opioids are increasing • Rates in all ages peaked in 2007 • Rates highest in 18-25 year olds (Johnston et al., 2009; SAMHSA, OAS, NSDUH, 2009) Initiation of Heroin Use • During the latter half of the 1990s, the annual number of heroin initiates rose to a level not reached since the late 1970s. • In 1974, there were an estimated 246,000 heroin initiates. • Between 1988 and 1994, the annual number of new users ranged from 28,000 to 80,000. • Between 1995 and 2001, the number of new heroin users was consistently greater than 100,000. • Between 2002 and 2008, the number of new heroin users ranged from 91,000 to 114,000. (SAMHSA, 2008; 2009) Other Opioid Use in a National Survey Population According to the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: • An estimated 6.9 million persons (2.8% of the U.S. population aged 12 or older) were currently using certain prescription drugs nonmedically. • An estimated 5.2 million were current users of pain relievers for nonmedical purposes. • Approximately 4.4 million persons had used OxyContin nonmedically at least once in their lifetime. • Non-medical pain reliever incidence increased from 1990 (628,000 initiates) to 2007, when there were 2.1 million new users. (SAMHSA, 2008; 2009a; 2009b) Emergency Department Visits Related to Heroin/Other Opioids According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network 2004-2008: • An estimated 200,666 drug misuse/abuse ED visits were related to heroin. • One-third (33%) of nonmedical use ED visits were related to Central Nervous System (CNS) agents. • Among CNS agents, the most frequent drugs were opiates/opioid analgesics, specifically: – Hydrocodone/combinations (22,912 visits) – Oxycodone/combinations (44,489 visits) – Methadone (23,498 ED visits) (SAMHSA, 2009) New Non-Medical Users of Pain Relievers • In 2008 – 2.2 million new non-medical users (a decline from 2.5 million in 2003, but still a lot!) • 6,000 new users per day • Among youth aged 12-17, females more likely to use non-medically • Among young adults aged 18-25, males more likely to use non-medically (SAMHSA, OAS, 2009) Treatment Admissions for Opioid Addiction Heroin & Other Opioid Treatment Admissions • TEDS admissions for primary opioid abuse increased from 16% of all admissions in 1997 to 19% in 2007. • Admissions for other opioids have increased consistently since the late 1990s – 1% to 5% between 1997 and 2007. (SAMHSA 2009). National Treatment Admissions for Heroin and Other Opiates in 2007 Percentage of Treatment Admissions by Age 25 20 15-17 15 18-19 10 20-24 5 0 Heroin Other Opiates (SAMHSA, OAS, 2009) Percent of Admissions Primary Heroin Treatment Admissions vs. Primary Other Opiate Treatment Admissions: A Side-by-Side Comparison 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% % Male % White Heroin Admissions (SAMHSA, OAS, 2009a; 2009b) % Injected % Rec'd Medication Other Opiate Admissions Substance Abuse Challenge: Prescription Drug Sources: Primarily Friends or Family Sources of Opioid Pain Relievers Used Non-Medically Source: SAMHSA, 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, September 2006 Prescription Drug Abuse: What are we talking about? Overview • Three classes of commonly abused Rx drugs (opioids, sedatives, stimulants) – What are they? – How do they act in the brain and body? – What are their effects? – Neurobiology What are opioids? • Opiate: derivative of opium poppy – Morphine – Codeine • Opioid: any compound that binds to opiate receptors – Semisynthetic (including heroin) – Synthetic – Oral, transdermal and intravenous formulations • Narcotic: legal designation Opioids Opioids: Acute Effects – Euphoria – Pain relief – Suppresses cough reflex – Histamine release – Warm flushing of the skin – Dry mouth – Drowsiness and lethargy – Sense of well-being – Depression of the central nervous system (mental functioning clouded) Long-Term Effects of Opioids Fatal overdose Collapsed veins Infectious diseases Higher risk of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis Infection of the heart lining and valves Pulmonary complications & pneumonia Respiratory problems Abscesses Liver disease Low birth weight and developmental delay Spontaneous abortion Cellulitis Opioid Receptors • Receptor types – mu, delta, kappa • Receptors located throughout body – Pain relief: central and peripheral nervous system – Reward and reinforcement: deep brain structures – Side effects: constipation, sedation, itch, mental status changes SOURCE: National Institute on Drug Abuse, www.nida.nih.gov. Endogenous Opioids • Produced naturally in body • Act on opioid receptors • Examples: endorphins, enkephalins, dynorphins, endomorphins • Produce euphoria and pain relief; naturally increased when one feels pain or experiences pleasure Opioid Withdrawal • • • • • • • • • • • Dysphoric mood Nausea or vomiting Diarrhea Tearing or runny nose Dilated pupils Muscle aches Goosebumps Sweating Yawning Fever Insomnia Opiates and Reward Opiates bind to opiate receptors in the nucleus accumbens: increased dopamine release Medication-Assisted Treatment Myths Myth #1: Medications are not a part of treatment. The pharmacotherapies that are FDA-approved for treatment of addiction should be used in conjunction with psycho-social-educational-spiritual therapy. Therefore, medications can be used as a part of treatment, but only one part. Medications are used in the treatment of many diseases, including addiction. Making the final decision about whether or not medications are a part of a client’s treatment is out of the counselor’s scope of practice. Medication-Assisted Treatment Myths Myth #2: Medications are drugs, and you cannot be clean if you are taking anything. The field needs to change terminology to reflect current trends. “Drugs” are illicit psychoactive substances that are used to achieve a “high.” “Medications” are available by prescription and are used to treat an illness, disorder or disease. Millions of Americans use medications (e.g., Zyban, nicotine patches) to quit smoking, and this practice is widely encouraged by addiction professionals. Physical dependence and addiction are not the same thing. The goal of addiction treatment is to assist a client in stopping his or her compulsive use of drugs or alcohol and love a normal, functional life. Medication-Assisted Treatment Myths Myth #2: Medications are drugs, and you cannot be clean if you are taking anything. If appropriately administered, medication-assisted treatment for addiction will not produce euphoric effects. Pharmacotherapies are effective. Clinical data suggest that clients perform better in treatment when psycho-social-educational-spiritual therapy is combined with appropriate pharmacotherapies. Medication-Assisted Treatment Myths Myth #3: Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) does not support the use of medications. Neither Alcoholics Anonymous (AA)/Narcotics Anonymous (NA) literature nor its founding members spoke or wrote against using medications. Even today, AA/NA does not endorse encouraging AA/NA participants to not use prescribed medications or to discontinue taking prescribed medications for the treatment of addiction. Medication-Assisted Treatment Myths Myth #3: Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) does not support the use of medications. • The Big Book states, “God has abundantly supplied this world with fine doctors, psychologists, and practitioners of various kinds. Do not hesitated to take your health problems to such persons. Most of them give freely of themselves, that their fellows may enjoy sound minds and bodies. Try to remember that though God has wrought miracles among us, we should never belittle a good doctor or psychiatrist. Their services are often indispensable in treating a newcomer and in following his case afterward.” (Chapter 9, Emphasis added) Behavioral Interventions Without question, medication interventions have been extremely effective and beneficial to the patient in early, as well as long-term recovery. However, it is imperative that pharmacotherapies are paired with some form of evidence-based behavioral therapeutic intervention. Behavioral Interventions Psychosocial therapy interventions that have been thoroughly researched and have shown good efficacy include: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Motivational Interviewing (MI) Motivational Incentives/Contingency Management The Addiction Technology Transfer Centers (ATTC) have developed helpful resources for evidence-based practices: www.nattc.org/resPubs/bpat/index.html . Medical Treatments for Opioid Addiction Partial vs. Full Opioid Agonist death Opiate Effect Full Agonist (e.g., methadone) Partial Agonist (e.g. buprenorphine) Antagonist (e.g. Naloxone) Dose of Opiate A Brief History of Medical Treatment for Opioids 1882 engraving of the British opium warehouse in Patna, India A Brief History of Opioid Treatment • Neolithic era (9000 B.C.E. to 3000 B.C.E.) Opium cultivated for food, anesthesia, and ritual purposes • 15th Century: Recreational use of opium reported, but use was limited by its rarity and expense • 1874: Heroin was first synthesized A Brief History of Opioid Treatment • 1964: Methadone is approved. • 1974: Narcotic Treatment Act limits methadone treatment to specifically licensed Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs). • 1984: Naltrexone is approved, but has continued to be rarely used (approved in 1994 for alcohol addiction). • 1993: LAAM is approved (for non-pregnant patients only), but is underutilized. A Brief History of Opioid Treatment, Continued • 2000: Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) expands the clinical context of medication-assisted opioid treatment. • 2002: Tablet formulations of buprenorphine (Subutex®) and buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone®) were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). • 2004: Sale and distribution of ORLAAM® is discontinued. Medications to Treat Addiction • Addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease characterized by compulsive use despite harmful consequences • Medications as part of comprehensive treatment plan • Treatment approaches: – Medications (Bio) – Therapy, lifestyle changes (Psycho-Social) • Thorough evaluation and diagnosis essential Pharmacotherapy in Substance Use Disorders • Treatment of withdrawal (“detox”) • Treatment of psychiatric symptoms or cooccurring disorders • Reduction of cravings and urges • Substitution therapy Naltrexone General Facts Generic Name: naltrexone hydrochloride Marketed As: ReVia and Depade Purpose: To discourage opioid use by reducing or eliminating the euphoric effects experienced by consuming exogenous administered opioids. Indication: In the treatment of alcohol dependence and for the blockade of the effects of exogenous administered opioids. Year of FDA-Approval: 1984 Naltrexone Administration Amount: one 50mg tablet Method: mouth Frequency: once a day Can be crushed, diluted or mixed with food. Abstinence requirements: must be taken at least 710 days after last consumption of opioids; abstinence from alcohol is not required; Appropriate Populations Age Range: 18 to 65 years old Adolescents: Has not been tested or FDA-approved. Elderly: Has not been tested or FDA-approved. Pregnancy: Has not been adequately tested on pregnant or nursing women; Pregnancy Category C designation, used only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. Polysubstance Abusers: Has not been adequately tested with this population. How Does Naltrexone Work? 1. Opioids enter the system and activate the areas of the brain known as the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens (the pleasure centers). 2. In response to this increased endogenous opioid activity, dopamine is released. 3. Since dopamine is a main reward neurotransmitter, increases in the nucleus accumbens makes the user feel good. 4. The brain remembers those good feelings caused by the dopamine and opioids. 5. The brain desires to repeat the behavior again to get the same good feelings. How Does Naltrexone Work? • Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist and blocks opioid N receptors. By blocking opioid receptors, the “reward” and acute reinforcing effects from dopamine are diminished, and alcohol consumption is reduced. N = naltrexone N N Post-Synaptic Neuron N Opioid Receptor N N Opioid Replacement Goals • • • • • Reduce symptoms & signs of withdrawal Reduce or eliminate craving Block effects of illicit opioids Restore normal physiology Promote psychosocial rehabilitation and nondrug lifestyle Methadone General Facts (information from medication package insert) Generic Name: methadone hydrochloride Marketed As: Methadose and Dolophine (among others) Purpose: To discourage illicit opioid use due to cravings or the desire to alleviate opioid withdrawal symptoms. Indication: For the treatment of moderate to severe pain not responsive to non-narcotic analgesics; for detoxification treatment of opioid addiction; for maintenance treatment of opioid addiction, in conjunction with appropriate social and medical services. Year of FDA-Approval: 1964 Methadone General Facts (information from medication package insert) • • • Amount: maintenance dose of 80 to 120mg Method: mouth Frequency: once a day • The effect of consuming food with methadone has not been evaluated and therefore, is not recommended. • Abstinence requirements: must be abstinent from opioids long enough to experience mild to moderate opioid withdrawal symptoms. • Initial dose will vary depending upon the client’s usage pattern, but should not exceed 40mg. Risk of Overdose: Just like with any opioid, overdose is possible. In the event of an overdose, appropriate medical treatment should be sought. Methadone General Facts (information from medication package insert) Pregnancy: Methadone is the preferred method of treatment for medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence in pregnant women. An expert review of published data on experiences with methadone use during pregnancy concludes that it is unlikely to pose a substantial risk. But, there is insufficient data to state that there is no risk. Methadone has not been adequately tested on pregnant women. Therefore, methadone has a Pregnancy Category C designation, meaning that it should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. Caution should be exercised when using methadone with this population. Methadone General Facts (information from medication package insert) Pregnancy: Detoxification is relatively contraindicated unless done in hospital with monitoring. Babies born to mothers who have been taking opioids regularly prior to delivery may be physically dependent and may experience opioid withdrawal symptoms. It is known that methadone is excreted through breast milk, and a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue the medication, taking into account the importance of the medication to the mother and continued illicit opioid use. Methadone General Facts (information from medication package insert) Addictive Properties: Chronic administration produces physical dependence. Since methadone is an opioid, it does have a high abuse liability and does produce withdrawal symptoms when the medication is ceased too abruptly or tapered down too quickly. Third-Party Payer Acceptance: Covered by most major insurance carriers, Medicare, Medicaid and the VA. Understanding DATA 2000 Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) • Expands treatment options to include both the general health care system and opioid treatment programs. – Expands number of available treatment slots – Allows opioid treatment in office settings – Sets physician qualifications for prescribing the medication DATA 2000: Physician Qualifications Physicians must: • Be licensed to practice by his/her state • Have the capacity to refer patients for psychosocial treatment • Originally limited to 30 patients later expanded to allow for 100 patients after the first year of experience • Be qualified to provide buprenorphine and receive a license waiver DATA 2000: Physician Qualifications A physician must meet one or more of the following qualifications: – – – – Board certified in Addiction Psychiatry Certified in Addiction Medicine by ASAM or AOA Served as Investigator in buprenorphine clinical trials Completed 8 hours of training by ASAM, AAAP, AMA, AOA, APA (or other organizations that may be designated by Health and Human Services) – Training or experience as determined by state medical licensing board – Other criteria established through regulation by Health and Human Services Development of Tablet Formulations of Buprnorphine • Buprenorphine is marketed for opioid treatment under the trade names of Subutex® (buprenorphine) and Suboxone® (buprenorphine/naloxone) • Over 25 years of research • Over 5,000 patients exposed during clinical trials • Proven safe and effective for the treatment of opioid addiction Buprenorphine: A Science-Based Treatment Clinical trials have established the effectiveness of buprenorphine for the treatment of heroin addiction. Effectiveness of buprenorphine has been compared to: • Placebo (Johnson et al. 1995; Ling et al. 1998; Kakko et al. 2003) • Methadone (Johnson et al. 1992; Strain et al. 1994a, 1994b; Ling et al. 1996; Schottenfield et al. 1997; Fischer et al. 1999) • Methadone and LAAM (Johnson et al. 2000) Why was Buprenorphine/Naloxone Combination Developed? • Developed in response to increased reports of buprenorphine abuse outside of the U.S. • The combination tablet is specifically designed to decrease buprenorphine abuse by injection, especially by out of treatment opioid users. Why Combining Buprenorphine and Naloxone Sublingually Works • Buprenorphine and naloxone have different sublingual (SL) to injection potency profiles that are optimal for use in a combination product. SL Bioavailability Injection to Sublingual Potency Buprenorphine 40-60% Buprenorphine ≈ Naloxone 10% or less Naloxone SOURCE: Amass et al., 2004. 2:1 ≈ 15:1 Buprenorphine/Naloxone: What You Need to know • Basic pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy is the same as buprenorphine alone. • Partial opioid agonist; ceiling effect at higher doses • Blocks effects of other agonists • Binds strongly to opioid receptor, long acting The Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction Induction Maintenance Tapering Off/Medically-Assisted Withdrawal Induction Induction Phase Working to establish the appropriate dose of medication for patient to discontinue use of opiates with minimal withdrawal symptoms, side-effects, and craving Direct Buprenorphine Induction from Short-Acting Opioids • Ask patient to abstain from short-acting opioid (e.g., heroin) for at least 6 hrs. and be in mild withdrawal before administering buprenorphine/naloxone. • When transferring from a short-acting opioid, be sure the patient provides a methadone-negative urine screen before 1st buprenorphine dose. SOURCE: Amass, et al., 2004, Johnson, et al. 2003. Direct Buprenorphine Induction from Long-Acting Opioids • Controlled trials are needed to determine optimal procedures for inducting these patients. • Data is also needed to determine whether the buprenorphine only or the buprenorphine/naloxone tablet is optimal when inducting these patients. SOURCE: Amass, et al., 2004; Johnson, et al. 2003. Direct Buprenorphine Induction from Long-Acting Opioids • Clinical experience has suggest that induction procedures with patients receiving long-acting opioids (e.g. methadone-maintenance patients) are basically the same as those used with patients taking short-acting opioids, except: – The time interval between the last dose of medication and the first dose of buprenorphine must be increased. – At least 24 hrs should elapse before starting buprenorphine and longer time periods may be needed (up to 48 hrs). – Urine drug screening should indicate no other illicit opiate use at the time of induction. Stabilization and Maintenance Stabilization Phase Patient experiences no withdrawal symptoms, side-effects, or craving Maintenance Phase Goals of Maintenance Phase: Help the person stop and stay away from illicit drug use and problematic use of alcohol 1. Continue to monitor cravings to prevent relapse 2. Address psychosocial and family issues Maintenance Phase Psychosocial and family issues to be addressed: a) Psychiatric comorbidity b) Family and support issues c) Time management d) Employment/financial issues e) Pro-social activities f) Legal issues g) Secondary drug/alcohol use Medically-Assisted Withdrawal (a.k.a. Dose Tapering) Buprenorphine Withdrawal • Working to provide a smooth transition from a physically-dependent to non-dependent state, with medical supervision • Medically supervised withdrawal (detoxification) is accompanied with and followed by psychosocial treatment, and sometimes medication treatment (i.e., naltrexone) to minimize risk of relapse. Medically-Assisted Withdrawal (Detoxification) • Outpatient and inpatient withdrawal are both possible • How is it done? – Switch to longer-acting opioid (e.g., buprenorphine) • Taper off over a period of time (a few days to weeks depending upon the program) • Use other medications to treat withdrawal symptoms – Use clonidine and other non-narcotic medications to manage symptoms during withdrawal Fitting Pharmacotherapies into Treatment Four Legs of Addiction Think of this concept as a chair, with each leg representing a component of a patient’s treatment plan. Psychological Biological Spiritual Social All four legs are required to “support” the patient, and if one leg is missing, the chair will be unstable and unable to accomplish its goal. Holistic Treatment The treatment plan must also address the multiple needs of the individual: sexual orientation disabilities gender differences employment issues homelessness developmental needs family dynamics co-occurring disorders children/prenatal care cultural, racial, religious norms legal issues For more information, contact: Thomas E. Freese, PhD tfreese@mednet.ucla.edu Download the presentation from: www.psattc.org Additional information on addiction research: www.uclaisap.org