2010_Pease_Treatment_of_Adults_with_Psychotic_disorders

advertisement

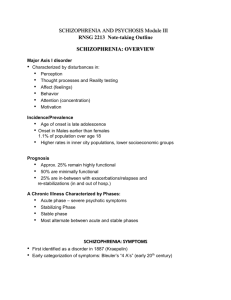

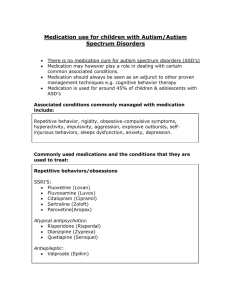

Meds, Medical Monitoring and More: Treatment of Adults with Psychotic Disorders Julie Keller Pease, M.D. MAPP 2010 Educational Session April 30, 2010 Meds DSM – IV lists 9 disorders under the category of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders Schizophrenia Schizophreniform disorder Schizoaffective disorder Delusional disorder Brief psychotic disorder Shared psychotic disorder Psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition Substance-induced psychotic disorder Psychotic disorder not otherwise specificed FDA Approved Indications for Antipsychotic Medications Schizophrenia Bipolar disorder Adjunct treatment of depression Irritability associated with autistic disorder Additional conditions treated with antipsychotics Psychotic disorders, including schizoaffective disorder, brief psychotic disorder, etc Mood disorders with psychotic symptoms, e.g. major depression with psychotic features Other psychiatric disorders: e.g. PTSD, OCD, personality disorders Aggression and irritability associated with Pervasive developmental disorders Disruptive behavior disorders Other psychiatric disorders, including personality disorders Behavioral and psychological symptoms associated with dementia, intellectual disability Agitation associated with delirium, drug withdrawal Tourette’s Miscellaneous Anti-emetic, anti-pruritic, intractable hiccups, insomnia, anxiety Most common uses of atypical antipsychotics Off label use accounts for ~ 1/3 of prescriptions Atypical Antipsychotic Use by Age Real and Projected Global Sales of Antipsychotics 1990-2009 ($ millions) Projected vs. Actual Sales of Antipsychotics (US$ Billions) 2005-2009 25 20 Projected Global Sales 15 Actual US Sales 10 Actual Global Sales 5 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Antipsychotics were the top therapeutic class in US Sales in 2008 and 2009 Timeline of Major Antipsychotic Therapies Paliperidone ECT, etc. Olanzapine Aripiprazole Quetiapine Chlorpromazine Fluphenazine Thioridazine Haloperidol Risperidone Clozapine (released in USA in Consta Ziprasidone 1990) 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2001 2003 2007 2009 – Paliperidone palmitate,asenapine,iloperidone The First “Modern” Antipsychotic Chlorpromazine (Thorazine®) Antipsychotic properties discovered in 1952 Studied originally for usefulness as a sedative Found to be useful in controlling agitation in patients with schizophrenia Introduced in U.S. in 1953 Typical antipsychotic medications High Potency (2-20 mg/day) (haloperidol,fluphenazine, thiothixene) Mid Potency (10-100 mg/day) (perphenazine, loxapine) Low Potency (300-800+ mg/day) (chlorpromazine, thioridizine) Dopamine blockade effects Limbic and frontal cortical regions: antipsychotic effect Basal ganglia: Extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) Hypothalamic-pituitary axis: hyperprolactinemia Typical Antipsychotics: Extrapyramidal side effects (EPS, EPSE) are common Parkinsonism Akathisia Dystonia Tardive dyskinesia (TD) Parkinsonian side effects Rigidity, tremor, bradykinesia, masklike facies Management: Lower antipsychotic dose if feasible Change to different drug (i.e., to an atypical antipsychotic) Anticholinergic medicines: benztropine (Cogentin) trihexyphenidyl (Artane) Akathisia Restlessness, pacing, fidgeting; subjective jitteriness; associated with suicide Resembles psychotic agitation, agitated depression Management: lower antipsychotic dose if feasible Change to different drug (i.e., to an atypical antipsychotic) Adjunctive medicines: propranolol (or another beta-blocker) benztropine (Cogentin), trihexyphenidyl (Artane) benzodiazepines Acute dystonia Muscle spasm: oculogyric crisis, torticollis, opisthotonis, tongue protrusion Dramatic and painful Treat with intramuscular (or IV) diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or benztropine (Cogentin) Tardive Dyskinesia (TD) Involuntary movements, often choreoathetoid Often begins with tongue or digits, progresses to face, limbs, trunk Etiologic mechanism unclear Incidence about 3% per year with typical antipsychotics Higher incidence in elderly Tardive Dyskinesia (TD) continued Major risk factors: high doses, long duration, increased age, women, history of Parkinsonian side effects, mood disorder Prevention: minimum effective dose, atypical meds, monitor with AIMS test Treatment: lower dose, switch to atypical, Vitamin E (?) Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) Fever, muscle rigidity, autonomic instability, delirium Muscle breakdown indicated by increased CK Rare, but life threatening – medical emergency Risk factors include: High doses, high potency drugs, parenteral administration Management: stop antipsychotic, supportive measures (IV fluids, cooling blankets, bromocriptine, dantrolene) Other common side effects of Typical Antipsychotics: Anticholinergic side effects: dry mouth, constipation, blurry vision, tachycardia Orthostatic hypotension (adrenergic) Sedation (antihistamine effect) Weight gain Limitations of Typical Antipsychotics Poor adherence due to side effects Poor treatment response in 30% of treated patients Incomplete treatment response in an additional 30% or more The First “Atypical” Antipsychotic: Clozapine Available in Europe, 1970 FDA approved 1990 For treatment-resistant schizophrenia 30% response rate in severely ill, treatmentresistant patients (vs. 4% with chlorpromazine/Thorazine) Receptor differences: Less D2 affinity, more 5-HT 10 Clozapine Helps Treatment-Resistant Patients Double Blind, Randomized Trial of Clozapine vs Chlorpromazine in Treatment Resistant Patients BPRS Schizophrenia Factor 16 14 12 10 clozapine chlorpromazine 8 6 4 2 0 0 1 2 3 Weeks in Trial 4 5 6 11 Clozapine: pros and cons Superior efficacy for positive symptoms Possible advantages for negative symptoms Virtually no EPS or TD Advantages in reducing hostility, suicidality Associated with agranulocytosis (1-2%) WBC count monitoring required Seizure risk (3-5%) Warning for myocarditis Significant weight gain, sedation, orthostasis, tachycardia, sialorrhea, constipation Costly Fair acceptability by patients Atypical antipsychotics (aka second-generation, novel) FDA approval 1990 1994 1996 1997 2001 2002 2003 2007 Generic Name clozapine risperidone olanzapine quetiapine ziprasidone aripiprazole risperidone MS paliperidone (Brand Name) (Clozaril) * (Risperdal) * (Zyprexa) (Seroquel) (Geodon) (Abilify) (Consta) (Invega) New Atypical Antipsychotics Paliperidone (Invega®) - Risperdal metabolite Very similar side effect profile to Risperdal Very similar effectiveness to Risperdal Asenapine (Saphris®) - another atypical antipsychotic Similar efficacy - similar safety Profile Iloperidone (Fanapt®) - another atypical antipsychotic No major efficacy benefits, QTc = ziprasidone Long-Acting Injectables Olanzapine (Zyprexa Relprevv®): 2-4 wks, safety concerns (PDSS) Paliperidone Palmitate (Sustenna®): monthly Sertindole (Serlect®) Bifeprunox Development discontinued Defining “atypical” antipsychotic Relative to conventional drugs: Lower ratio of D2 to 5-HT2A receptor affinity Lower propensity to cause EPSE (extrapyramidal side effects) due to weaker D2 binding/antagonism Atypical Antipsychotics: Side Effects • Atypical antipsychotics tend to have better subjective tolerability (except clozapine) • Atypical antipsychotics much less likely to cause EPSE and TD, but may cause more: • Weight gain • Metabolic problems (lipids, glucose) Summary: ADA/APA Consensus Conference on Antipsychotic Drugs and Obesity and Diabetes Drug Weight Gain Risk for Diabetes Worsening Lipid Profile Clozapine (Clozaril) +++ + + Olanzapine (Zyprexa) +++ + + Risperidone (Risperdal) Paliperidone (Invega) ++ D D Quetiapine (Seroquel) ++ D D Aripiprazole* (Abilify) +/- -- -- Ziprasidone* (Geodon) +/- -- -- + = increase effect; -- = no effect; D = discrepant results *newer drugs with limited long-term data Source Diabetes Care; Volume 27, Number 2, Feb 2004 Weight gain at 10 weeks 6 5 4 Kg 3 2 1 Allison et al 1999 CLOZ CPZ OLZ RISP ZIP HAL -1 PLB 0 Mean change in weight (kg) Change in Body Weight Following Switch to Aripiprazole-8 Wk Study 1 0 † -1 -2 * -3 n= Olanzapine Risperidone Haloperidol 169 106 14 Prior antipsychotic *p<0.001; †p=0.077 LOCF analysis. Casey, et al. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(suppl 1):S187. Estimated Weight Change (lb) After Switch to Ziprasidone† Weeks 10 14 6 19 23 27 32 36 40 45 49 53 58 0 * -5 *** ** -10 *** -15 -20 ** Improvement LS Mean Change, lb 5 *P<0.05 **P<0.001 ***P<0.0001 *** -25 †Repeated Switched from Conventionals Olanzapine measures analysis Risperidone Presented at APA 2004, New York, NY QTc Prolongation Drugs with Risk of Torsades de Pointes Haloperidol Mesoridazine Thioridazine Pimozide Chlorpromazine Erythromycin Methadone Quinidine Drugs with Possible Risk of Torsades Paliperidone Quetiapine Risperidone Ziprasidone Iloperidone Asenapine Sertindole Lithium Source: www.azcert.org: QTdrugs.org Advisory Board of Arizona CERT Side Effects of Atypical Antipsychotics CLOZAPINE PALIPERIDONE RISPERIDONE OLANZAPINE QUETIAPINE ZIPRASIDONE ARIPIPRAZOLE Low Blood Pressure +++ + +/0 ++ 0/+ 0/+ Dry Mouth, constipation +++ 0 +/++ 0 0 0 EPSE, ↑ prolactin 0 +/++ 0/+ 0 +/0 0 Sedation +++ +/- ++ +++ 0 0 Weight Gain ++++ + ++++ ++ +/- +/- Lipids +++ + +++ ++ 0 0 ↑ Blood Sugar +++ + +++ ++ 0 0 Summary of Antipsychotic Side Effects Side Effect Higher Liability Lower Liability EPS Conventional antipsychotics Conventional antipsychotics CLZ, OLZ, QTP TD CLZ, OLZ, QTP Hyperprolactinemia Conventional CLZ, OLZ, QTP antipsychotics, RIS Sedation CPZ, CLZ, QTP, OLZ RIS, ARIP, ZIP Anticholinergic CPZ, CLZ RIS effects thioridazine, pimozide, CPZ, QTc prolongation mesoridazine, haloperidol Weight gain CPZ, CLZ, OLZ Hyperglycemia, DM Atypical antipsychotics HAL, ZIP Long-acting injectable (depot) antipsychotics Until late 2003, only haloperidol and fluphenazine available in the U.S. Long-acting risperidone introduced late 2003, long-acting paliperidone, olanzapine in 2009 Injections every 2 weeks (fluphenazine, risperidone, olanzapine) or 4 weeks (haloperidol, paliperidone, olanzapine) Goal is to decrease non-adherence and thus reduce relapse Used more commonly in other countries, and in states with outpatient commitment Are second-generation antipsychotics more effective than first-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia? The CATIE Schizophrenia Trial CUTLASS Rosenheck et al, AJP cost-effectiveness Luecht el al, Lancet 2009 meta-analysis NICE Guidelines Updated APA Practice Guidelines Proportion of Patients Continuing Treatment CATIE Study Phase 1: Time to Discontinuation for Any Cause Olanzapine (N=330) Perphenazine (N=257) 1.0 0.9 Risperidone (N=333) Quetiapine (N=329) Ziprasidone (N=183) 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0 3 6 9 12 15 Time to Discontinuation for Any Cause (months) Lieberman JA et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209-1223. 18 Proportion of Patients Continuing Treatment CATIE Study Phase 2T: Time to Discontinuation for Any Cause 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 Time to Phase 2 Discontinuation (months) Olanzapine (N=66) Quetiapine (N=63) Stroup TS et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2006; 163:611-622. Risperidone (N=69) Ziprasidone (N=135) Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUTLASS) 227 patients with schizophrenia who were judged by their treating clinician to potentially benefit from a new antipsychotic medication trial "because of inadequate response or adverse effects" were randomized to receive either a first- or a second-generation antipsychotic (excluding clozapine). The specific antipsychotic was chosen by the treating clinician. The primary outcome measure, assessed by blind raters at 12, 26, and 56 weeks, was "quality of life" reflecting social and vocational function. Symptom changes were secondary outcomes. There was no difference in any outcome measures between groups. Average Monthly Symptom Scores Rosenheck R et al. Cost Effectiveness of Second-Generation Antipsychotics and Perphenazine in a Randomized Trial of Treatment for Chronic Schizophrenia Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:2080-89 Comparison of second-generation vs firstgeneration drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis (Leucht, et al, Lancet 2009) Clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone were better than firstgeneration drugs for overall efficacy, with small to medium effect sizes Other second generation drugs were NOT more efficacious, even for negative symptoms Second-generation drugs induced fewer EPSE than haloperidol, but only a few have fewer EPSE than low potency first-generation drugs BUT: Second-generation drugs induced more weight gain (except ziprasidone and aripiprazole) Only clozapine demonstrated improved quality of life compared to older drugs Atypicals are very expensive – cost effectiveness not proven Need more rigorous studies to accurately define older firstgeneration drugs Antipsychotic medication reduces relapse rates: but……not all SGA > FGA Risk of relapse in one year: Consistently taking medications: 20-30% Not taking medications consistently: 65-80% Leucht, et al; Lancet 2009: olanzapine and risperidone significantly better than first-generation antipsychotics in preventing relapse. Aripiprazole and clozapine: no significant difference. No studies available for other second-generation antipsychotics Updated APA Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Schizophrenia Guideline Watch (November 2009): The 2004 guideline recommends that selection of an antipsychotic agent be guided by the patient's past medication history, current symptoms and co-occurring conditions, other concurrent treatments, and preferences. The guideline states that secondgeneration agents should be considered first-line options for patients in the acute phase, mainly because of the decreased risk of extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia, but acknowledges debate over the relative advantages, disadvantages, and cost-effectiveness of first- and secondgeneration agents. The guideline also states that for some patients, a first-generation agent may be an appropriate first-line option. This latter recommendation has been strengthened by the results of several recently published effectiveness studies that suggest that the first-generation antipsychotics perphenazine and molindone may be equally effective as second-generation agents. In fact, the distinction between first- and second-generation antipsychotics appears to have limited clinical utility. Updated NICE Guidelines for Treatment of Schizophrenia (UK) Pharmacological interventions For people with newly diagnosed schizophrenia, offer oral antipsychotic medication. Provide information and discuss the benefits and side-effect profile of each drug with the service user. The choice of drug should be made by the service user and healthcare professional together, considering: − the relative potential of individual antipsychotic drugs to cause extrapyramidal side effects (including akathisia), metabolic side effects (including weight gain) and other side effects (including unpleasant subjective experiences) − the views of the carer where the service user agrees. Do not initiate regular combined antipsychotic medication, except for short periods (for example, when changing medication). Medical Monitoring Medical Issues in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Factor Prevalence in Schizophrenia Prevalence in Bipolar Prevalence in General Population Smoking 75% 43-75% 25% Obesity 50% 58% 33% 13-14% 9.9-26% 7% HIV 3% ? 0.3% Hepatitis C 20% ? 1.8% Diabetes Mellitus Other: -inactivity, poor nutrition -substance use Meyer JM and Nasrallah H eds. Medical Illness and Schizophrenia. APPI 2003 Regenold WT, et al. Increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among psychiatric inpatients with bipolar I affective and schizoaffective disorders independent of psychotropic drug use. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002 Jun;70(1):19-26 Health Risk Maine DIG Surveys (Age 18-64 Years) Health Risk Age Group 2007 DIG Survey (n=731) 2008 DIG Survey (n=1190) 2007 Maine BRFSS Smoking 18-44 45-64 46.1% 49.5% 50.5% 45.7% 26.3% 18.8% Obesity 18-44 45-64 49.4% 49.6% 45.9% 47.1% 26.0% 27.6% High Cholesterol 18-44 45-64 40.5% 38.6% 29.2% 48.0% 23.2% 46.0% High Blood Pressure 18-44 45-64 34.0% 34.7% 24.3% 45.6% 13.5% 34.0% Chronic Health Conditions Maine DIG Surveys (Age 18-64 Years) Health Risk Age Group 2007 DIG Survey (n=731) 2008 DIG Survey (n=1190) 2007 Maine BRFSS Chronic Disease* 18-44 45-64 29.6% 31.5% 19.2% 36.8% 3.8% 14.8% Cardiovascular Disease** 18-44 45-64 11.3% 9.7% 5.3% 14.3% 1.3% 7.7% Diabetes 18-44 45-64 23.0% 25.5% 15.1% 29.2% 2.7% 9.4% * Chronic Disease = reported CVD or diabetes ** Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) = reported angina or heart attack Multi-State Study Mortality Data: Years of Potential Life Lost Year AZ MO OK 1997 26.3 25.1 28.5 1998 27.3 25.1 28.8 29.3 26.3 29.3 26.9 1999 32.2 26.8 2000 31.8 27.9 RI TX UT OH 24.9 1998 2002 32.0 Compared with the general population, persons with major mental illness typically lose more than 25 years of normal life span Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Preventing Chronic Disease. Apr 2006;3:1-14 Miller BJ, et al. Psych Services Oct 2006; 57: 1482-87 Shift in Risk Perception of Antipsychotics Past Areas of Concern Current Medical Realities Diabetes Weight Gain Weight Gain Sedation Tardive Dyskinesia Insulin Resistance CHD Prolactin Hyperlipidemia Prolactin TD Hyperlipidemia Insulin Resistance Sedation Coronary Heart Disease Undertreatment of Common Disorders in the CATIE Schizophrenia Trial at Enrollment Treated Untreated 100 75 88.0 69.8 62.4 50 37.6 30.2 25 12.0 0 Diabetes Mellitus Hypertension Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM et al. Schiz Res 2006. Dyslipidemia Clinical Issues: barriers to medical monitoring Lack of access to medical care for patients with severe mental illnesses Lack of access to support/consultation for PCP Lack of coordination/collaboration between mental health, primary care, laboratory Switching to more metabolically neutral medications may reverse many problems, but requires careful attention by the psychiatrist and motivation by the client Physical and Laboratory Assessment at Diagnosis: APA Practice Guidelines Vital Signs BMI CBC, CMP, Thyroid, FBG, Lipids, other infection, βHCG, toxicology screen, EKG, Prolactin imaging Neurological exam (EPS, TD) Eye exam (Cataracts) Monitoring Equipment Medical Monitoring: What We Should Be Doing Inquiry Personal or family history: Diabetes Hypertension CHD (MI or Stroke) Cigarette smoking Diet Physical Activity Substance use Measure Height Weight BMI Waist circumference Blood Pressure Lab Fasting Glucose Fasting Lipids ADA Screening Guidelines for Patients on Second-generation Antipsychotics Baseline Personal Family History X Weight (BMI) X Overweight (25.0 – 29.9) Obese (≥30.0) Waist circumference (<40” in males, <35” in females) 4 weeks 8 weeks 12 weeks Annually X X X X X quarterly X Blood Pressure X X X Fasting Plasma Glucose X X X (HbA1c) (HbA1c) X X IFG (100 – 125 mg/dL) Diabetes (>125 mg/dL) Fasting Lipid Profile 5 yrs Total cholesterol (<200) HDL (>40), LDL (<100), TG (<150) Normal Values (in parentheses) based on 2007 ADA Guidelines and National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Guidelines. More frequent assessments may be warranted based on patient results and the monitoring recommendations in package inserts for individual medications used. The 5 A’s for obesity mgmt ASK (history, risk factors, correlations between medications and weight change) ADVISE and educate ASSESS motivation, barriers, wt. goals ASSIST (nutrition education, referrals) BMI > 30 consider weight loss agent BMI >40 explore bariatric surgery ARRANGE follow-up, review goals and intervention options, congratulate successes Weight Control Strategy Worksheet Try to keep your appetite tamed - Eat small portions frequently instead of full meals or large portions infrequently to keep your appetite from building and overeating when you do eat. - Eat more slowly to give the “I ate” signals time to get to your brain from your stomach - Keep your mind occupied with other activities. Delay eating by choosing to do another activity before you eat or snack. - Learn relaxation or mindfulness, and practice it daily ↓↓↓ Try to keep your intake down ↓↓↓ - Keep a journal or log to make yourself aware of your food intake - Use smaller sized plates & glasses to make a “full” portion with less food. - Keep a calorie count - Beware “hidden” calories, especially in soda etc. - Make sure you have plenty of low calorie and high fiber (makes you feel full) food around to do your eating with, especially the food you use to eat small portions often - Swap vegetables for sweets, swap pretzels for chips - Drink plenty of water - Avoid fruit juices and sodas – drink water or seltzer instead of other cold drinks - Drink your coffee or tea “black” – without sugar, creamer, milk or sweeteners - ↑↑↑ Try to keep your energy output up ↑↑↑ - Exercise daily – brisk walks (striding fast enough so you could converse but it would be “breathy”) are thought to be a “best” exercise – 30 minutes to an hour daily. Two 15 minute walks equals one 30 minute walk if time is a problem. - Seek active rather than sedentary activities - Take stairs rather than elevators. - Plan your errands and activities to include walking - Keep a journal or log to make yourself aware of your activity level - Pharmacologic Interventions for weight loss FDA- approved use only if BMI >30 or >27 if metabolic syndrome is present Initiate only after a 6-month period with weight loss <1 lb/week despite adherence to “healthy lifestyle regimen” Sibutramine, Orlistat, Phentermine Off-label Glucophage (Metformin) Topiramate Bupropion + naltrexone, phentermine + topiramate, bupropion + zonisamide New/investigational Lorcaserin (selective serotonin 2C receptor agonist) Betahistine (H1 agonist/H3antagonist) Managing Side Effects of Your Medication The most common side effects of antipsychotic medications are: Dry mouth, constipation, lack of energy, drowsiness, upset stomach, dizziness, feeling hungrier than usual, gaining weight, insomnia, tremors, and restlessness. These side effects generally do not bother people enough to stop taking their medications. Here are some suggestions for managing side effects: If you experience this… Sleep disturbance Try this: Feeling hungrier than usual Gaining weight Dizziness Dry mouth Constipation Upset stomach Restlessness Talk with your doctor about adjusting the doses or timing of your medication schedule Drink plenty of water or other sugar-free drinks – 6 to 8 glasses a day. Drink a glass of water before meals to help you feel fuller. When you want a snack, try eating a half-cup of fruit or raw vegetables or a rice cake. Chew sugar-free gum. Instead of snacking, try taking a walk. Get some extra exercise each day. Talk with your doctor before making any major changes in your exercise routine. Stand up slowly if you have been sitting or lying down. If you become anxious, try diaphragmatic breathing or relaxation. Enjoy sugar-free mints or sugar-free hard candy. Let them melt in your mouth. Eat foods that are high in fiber, such as bran cereals and raw vegetables. Try taking your medication with a meal Talk to your doctor about a dosage change. Talk to your doctor about medication options for managing this side effect. **Contents of this handout courtesy of Eli Lilly and Co. – modified by Julie Pease, M.D. Informed Consent PATIENT MEDICATION CONSENT, AGREEMENT TO REPORT ADVERSE SYMPTOMS, and ASSUMPTION OF RISK AGREEMENT Note: No medication is absolutely positively 100% risk free. Even taking over-the-counter medicines, like Aspirin and Tylenol for example, can result in serious side effects or even death. However, all prescribed medicines are approved as safe and effective by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and most of the time they cause little or no harm. Nevertheless, there are some specific concerns that you should be aware of with certain medicines that are commonly prescribed, and that is the purpose of this medication consent. 1. Atypical Antipsychotics (ABILIFY, CLOZARIL, GEODON, RISPERIDAL, SEROQUEL, SYMBYAX, and ZYPREXA): These may cause or result in certain adverse medical problems: a. Elevated blood sugar, diabetes, and weight gain: elevated blood sugars, in some cases extreme and associated with coma or death, have been reported in patients treated with these medications. These changes may occur with or without weight gain. I agree to report any significant weight gain and/or symptoms of elevated blood sugar (including increased thirst, increased urination, increased eating, and weakness) to my doctor. Patients who develop any of these symptoms should have a test for elevated blood sugar and cholesterol. b. Increased risk of stroke and a higher death rate in elderly patients with dementia. These medications are not indicated for the treatment of agitation except in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. a. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS): this is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition with symptoms of unstable blood pressure, confusion, coma, delirium, fever, and/or muscle stiffness. b. Elevated prolactin levels: this may be associated with enlarged breasts, breast discharge, sexual dysfunction, osteoporosis, and very rarely pituitary (brain) tumors. 2. Tardive Dyskinesia (TD): All antipsychotic medications, including haloperidol (HALDOL) and fluphenazine (PROLIXIN), those listed in #1 above, and others such as _______________________ may result in a condition called tardive dyskinesia (TD). The symptoms of TD, which are primarily abnormal movements or muscle cramps and which may be irreversible, have been explained to me and I accept the risk and agree to report any muscle cramps or abnormal movements to my doctor immediately. 6.Pregnancy: Taking medication during pregnancy exposes the fetus to medication and can present a risk to the unborn child. Some psychiatric medications are known to have a higher risk of birth defects (e.g. Depakote); others may be continued during pregnancy with minimal risk depending upon the medication and the circumstances. This needs to be considered carefully in the decision making process for medication use by women of childbearing ages. If planning to become pregnant, I agree to discuss my medications with my doctor before trying to conceive. If I do become pregnant while taking medication, I agree to call my doctor immediately so that we can discuss the risks/benefits of continuing medication or the need/process by which to stop the medication if the situation and risks of continuing warrant that. All medications are passed into breast milk in differing amounts. Some may be used with relative safety during breastfeeding and others are not recommended for use during lactation. 10. Off-label Use: One or more of the medications I have been prescribed is or are prescribed “off-label.” This means that the medication is prescribed for a use not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), use at doses above those recommended, or use for periods of time longer than approved. 11. Driving a Car or Use of Machinery OR Use With Alcohol: One or more of the medications prescribed to me may adversely affect my ability to drive a motor vehicle or operate machinery. I agree not to drive or operate machinery if I feel even slightly impaired, and I take full responsibility for this liability. MEDICATIONS SHOULD NOT BE TAKEN OR USED WITH ALCOHOL. 13. Potential risks and benefits of taking this or these medications, as well as alternative treatments, have been discussed with me and I accept these risks. I was given an opportunity to discuss my medications, all of my questions have been satisfactorily answered, and I was given a copy of this form to take home with me. ____________________________________________ PATIENT SIGNATURE Date ____________________________________________ Parent/Guardian Signature Date _______________________________________ Prescriber’s Signature Date Copyright © safePrescribing.com 2007 - Internet Resources www.psych.org (Practice Guidelines) www.mainepsych.org *new website coming soon www.tobaccofreemaine.org www.mayoclinic.com (Metabolic syndrome, wt loss) www.nami.org (Diagnosis, medication, support info.) www.cdc.gov/HealthyLiving/ www.mainecarepdl.org/index.pl/home/ps ych-work-group-pwg (Monitoring recommendations) www.azcert.org (QT Drug Lists and DDI Lists) Conclusions • Except for clozapine, most of the currently available agents, including the newest atypicals, are more alike than different in terms of effectiveness • Safety and avoidance of metabolic side effects are major reasons to choose certain medications • Providers have a duty to monitor weight, blood pressure, blood sugar and lipids, and to support healthy lifestyle choices • Consider long-acting injectable medications for treatment of psychosis in cases of relapse due to nonadherence • Providers should consider alternatives to antipsychotics when treating non-psychotic disorders More Treatment-Resistant Psychotic Disorders Reconsider diagnosis Evaluate adequacy of medication trials Consider a trial of clozapine Consider augmenting medication Consider ECT Consider Cognitive Behavior Therapy On The Horizon Some features of schizophrenia may be due to decreased levels of activity at NMDA glutamate receptors Glycine and related compounds can stimulate those receptors and might prove useful as a treatment for schizophrenia Glycine Transport Inhibitors (GlyT1 Blockers) The GlyT1 transporter is localized to important areas of the brain Sarcosine: enhances NDMA receptor function by inhibiting glycine uptake How A Reuptake Inhibitor Works Presynaptic Nerve Ending Glycine Reuptake Pump Synaptic vesicles with Glycine Glycine Postsynaptic Neuron NMDA Receptors Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous illness Defined by a constellation of symptoms, including psychosis Multifactorial etiology, variable course Social/occupational dysfunction a required diagnostic criterion Good treatment must address all aspects of dysfunction Features of Schizophrenia Positive symptoms Delusions Hallucinations Functional Impairments Work/school Interpersonal relationships Self-care Cognitive deficits Attention Memory Verbal fluency Executive function (e.g., abstraction) Disorganization Speech Behavior Negative symptoms Anhedonia Affective flattening Avolition Social withdrawal Alogia Mood symptoms Depression/Anxiety Aggression/Hostility Suicidality Treatments for schizophrenia: Strong evidence for effectiveness Antipsychotic medications Family psychoeducation Assertive Community Treatment (ACT teams) Family Psychoeducation Provides information about schizophrenia: course, symptoms, treatments, coping strategies Supportive One aim is to decrease expressed emotion (hostility, criticism, etc.) Not blaming Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) ACT is effective evidence-based treatment Supported by 25 randomized controlled trials Reduces hospitalization rates No more expensive than traditional care More satisfactory to patients Individualized, multidisciplinary treatment ACT is also called Training in community living PACT (Program for Assertive Community Treatment) Continuous treatment teams Intensive psychiatric community care (in VA system) Riverview: Progressive Treatment Program Other interventions for schizophrenia: Some evidence for effectiveness Some types of psychotherapy Case management Vocational rehabilitation Outpatient commitment ECT (for catatonia) CBT for Schizophrenia CBT is helpful for refractory or breakthrough psychotic symptoms Requires high insight (“I can’t trust my perceptions because I am sick”.) CBT for delusions Direct confrontation should be avoided Focus not on the belief but on the evidence for it Encourage development of arguments against beliefs by patients CBT for Schizophrenia CBT for hallucinations Distraction method (Extinguishing) Wearing headphones to focus attention away so the hallucinations are extinguished with decreased reactivity Focusing method (Desensitization) Describe, record and recognize the connection between stressors and hallucinations Explore what the voices mean to them Use self-talk to cope with hallucinations Negative symptoms Activity scheduling Skills training Schizophrenia Treatment: Case management • Case manager helps coordinate treatments, provides support • Help navigating life, such as managing every day activities, transportation, etc. • Helps broker access to available services • Benefits: improves compliance, reduces stressors, helps identify and treat problems with substance use Schizophrenia Treatment Psychosocial Remedial Therapies • To improve social and vocational skills • Clubhouse model offers opportunities to socialize, transitional employment • Vocational rehabilitation—especially supported employment DSM-IV Schizophrenia 2 or more of the following for most of 1 month: Delusions Hallucinations Disorganized speech Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior Negative symptoms Social/occupational dysfunction Duration of at least 6 months Not schizoaffective disorder or a mood disorder with psychotic features Not due to substance abuse or a general medical disorder Schizophrenia Lifetime prevalence rates range from .5% to 1% Low incidence rate – 1 per 10,000 per year, but very debilitating disorder Onset from adolescence to age 45 Affects men and women equally - men have earlier onset (18-25) than women (25-35)