Harlem Renaissance Poetry: Langston Hughes

advertisement

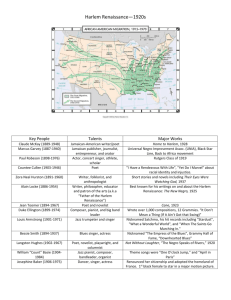

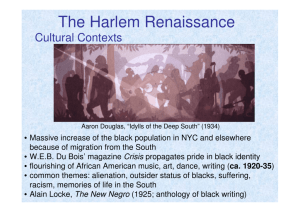

The Harlem Renaissance The Harlem Renaissance is the name given to the period from the end of World War I and through the middle of the 1930s Depression. During this time a group of talented African-American writers produced a sizable body of literature in these four areas: poetry fiction drama and essays The Harlem Renaissance also involved art . . . and music; however, we will be focusing on the literature of that period. Common themes of the Harlem Renaissance include the following: alienation marginality folk material the blues tradition and the problem of writing for an elite audience. The Harlem Renaissance was more than just a literary movement. racial integration racial consciousness the explosion of music, particularly jazz. the " back to Africa" movement led by Marcus Garvey The Harlem Renaissance brought the Black experience into American cultural history. The Black migration, from south to north, changed their image from rural to urban, from peasant to sophisticate. Harlem became a crossroads where Blacks interacted and expanded their contacts internationally. The Harlem Renaissance profited from a spirit of self-determination which was widespread after W.W.I. The "renaissance" echoed American progressivism in its faith in democratic reform, in its belief in art and literature as agents of change, and in its almost uncritical belief in itself and its future. Both black and white intellectuals were unprepared for the rude shock of the Great Depression. As a result the Harlem Renaissance was shattered by it because of naive assumptions about the centrality of culture, unrelated to economic and social realities Yet the Harlem Renaissance was very significant because it became a symbol and a point of reference for everyone to remember. The name, more than the place, became synonymous with new vitality, black urbanity, and black militancy. It became a racial focal point for Blacks the world over; it remained for a time a race capital. The audience for black poetry at this time was largely white, and white expectations influenced black expression both in music and in poetry. Modernism was the dominant movement in expression at this time, and many modernist things in art came from non-western or “primitive” cultures. Harlem Renaissance Poetry: Langston Hughes The first poem to really draw attention to Langston Hughes was “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” which helped define his style as a Negro poet. He wrote it when he was only 17, riding on a train which crossed the Mississippi River going from Illinois to Missouri. The Negro Speaks of Rivers I’ve known rivers: I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young. I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep. I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it. I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom burn all golden in the sunset. I’ve known rivers: Ancient, dusky rivers. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. Interpretation of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” A powerful poem may convey its message with simple language and just one strong central image. An example of such a poem is “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” by Langston Hughes, one of major poets of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920’s. In simple yet eloquent language, Hughes uses the central image of a river as a symbol to represent the soul of African Americans. In the title of his poem, Hughes indicates that he is speaking for all African Americans. In the line “My soul has grown deep like the rivers,” Hughes directly compares his soul to a river. He then presents images of those rivers that have been important in African American history. He conjures up images of the dawn of civilization along the Euphrates in southwest Asia, of early peaceful African societies along the Congo, of the great Egyptian civilization along the Nile in Africa, and of slave life along the Mississippi in the New World. These images convey the proud, noble, and yet troubled heritage of African Americans. Hughes uses such words as “deep,” “golden,” “ancient,” and “dusky” to describe rivers, adjectives that are also meant to describe African Americans. Like the rivers Hughes names, African Americans have an ancient history, but one filled with many difficulties in modern times. Hughes suggests that this history, with its more recent troubles, has brought a profound depth to the African American experience. He is saying that the collective soul of African Americans is ancient and deep, like a river. Thus, with one central image – that of a river – and a few carefully chosen adjectives, Hughes conveys the proud and noble heritage of African Americans and celebrates the depth of their collective experience, the depth of their soul. I, Too by Langston Hughes 1924 (he was 22 years old) I, too, sing America [An allusion to Walt Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing,” published in 1867 in Leaves of Grass. Here Hughes means that blacks are Americans too, not just whites.] I am the darker brother. [This poem is about segregation and how eventually it will come to an end.] They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes. But I laugh, [The implied meaning here is that they are waiting now but will grow stronger as time passes.] And grow strong. Tomorrow, I’ll sit at the table When company comes. [The use of "I" helps showing the African American community will soon rise and be one with the rest of America.] Nobody’ll dare Say to me, “Eat in the kitchen,” [This shows what the future will be like, or as Hughes uses the metaphorical "tomorrow." The use of "I" helps show that the African American community will soon rise and be one with the rest of America.] Then. Besides, They’ll see how beautiful I am And be ashamed – I, too, am America. [Here Hughes says that once African American's are recognized as equal, everyone will see they are not bad and that they are beautiful as well as part of America.] The Weary Blues Langston Hughes (1923) Droning a drowsy syncopated tune, Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon, I heard a Negro play. Lines 1-3 create a relationship between speaker and subject. Hughes suggests that the blues offer an experience for not only the artist but also the community. Down on Lenox Avenue the other night By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light He did a lazy sway .... He did a lazy sway .... To the tune o' those Weary Blues. With his ebony hands on each ivory key He made that poor piano moan with melody. O Blues! Lenox Avenue is a main street in Harlem, which in terms of the geography of New York, is North, or uptown. Because Harlem was home mainly to African Americans and the parts of New York City south of Harlem (referred to as "downtown") were populated mainly by whites, if the speaker were to perceive Lenox Avenue as "up" from his place of origin, we might assume that he is white. Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool. Sweet Blues! Coming from a black man's soul. O Blues! In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan-"Ain't got nobody in all this world, Ain't got nobody but ma self. I's gwine to quit ma frownin' And put ma troubles on the shelf." Hughes uses the word "raggy" in line 13. "Raggy" is not an actual word; perhaps we might interpret it as a combination of word "raggedy" meaning tattered or worn out and the word "ragtime" which refers to a style of jazz music characterized by elaborately syncopated rhythm in the melody and a steadily accented accompaniment. When we think of “raggedy” we think of patchwork, and the blues is a type of patchwork of various types of music. Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor. He played a few chords then he sang some more-"I got the Weary Blues And I can't be satisfied. Got the Weary Blues And can't be satisfied-I ain't happy no mo' And I wish that I had died." And far into the night he crooned that tune. The stars went out and so did the moon. The singer stopped playing and went to bed While the Weary Blues echoed through his head. He slept like a rock or a man that's dead. The speaker of Langston Hughes's "The Weary Blues" describes an evening of listening to a blues musician in Harlem. With its diction, its repetition of lines and its inclusion of blues lyrics, the poem evokes the mournful tone and tempo of blues music and gives readers an appreciation of the state of mind of the blues musician in the poem. America by Claude McKay Although she feeds me bread of bitterness, And sinks into my throat her tiger's tooth, Stealing my breath of life, I will confess I love this cultured hell that tests my youth! Her vigor flows like tides into my blood, Giving me strength erect against her hate. Her bigness sweeps my being like a flood. Yet as a rebel fronts a king in state, In this poem written as a sonnet, McKay shows both positive and negative feelings I stand within her walls with not a shred about America. Of terror, malice, not a word of jeer. The first stanza accuses, yet he loves his country. Darkly I gaze into the days ahead, And see her might and granite wonders there, McKay goes on to talk of his love / hate relationship with America. The mother image deepens the reader’s sympathy Beneath the touch of Time's unerring hand, Like priceless treasures sinking in the sand. for his character. The last couplet infers that wonderful possibilities are in . America (equality for all) but are still hidden. Go Down, Death by James Weldon Johnson Johnson wrote this as a funeral sermon in 1927. Weep not, weep not, She is not dead; She's resting in the bosom of Jesus. Heart-broken husband--weep no more; Grief-stricken son--weep no more; Left-lonesome daughter --weep no more; She only just gone home. Day before yesterday morning, God was looking down from his great, high heaven, Looking down on all his children, And his eye fell on Sister Caroline, Tossing on her bed of pain. And God's big heart was touched with pity, With the everlasting pity. And God sat back on his throne, And he commanded that tall, bright angel standing at his right hand: Call me Death! And that tall, bright angel cried in a voice That broke like a clap of thunder: Call Death!--Call Death! And the echo sounded down the streets of heaven Till it reached away back to that shadowy place, Where Death waits with his pale, white horses. And Death heard the summons, And he leaped on his fastest horse, Pale as a sheet in the moonlight. Up the golden street Death galloped, And the hooves of his horses struck fire from the gold, But they didn't make no sound. Up Death rode to the Great White Throne, And waited for God's command. And God said: Go down, Death, go down, Go down to Savannah, Georgia, Down in Yamacraw, And find Sister Caroline. She's borne the burden and heat of the day, She's labored long in my vineyard, And she's tired-She's weary-Go down, Death, and bring her to me. And Death didn't say a word, But he loosed the reins on his pale, white horse, And he clamped the spurs to his bloodless sides, And out and down he rode, Through heaven's pearly gates, Past suns and moons and stars; on Death rode, Leaving the lightning's flash behind; Straight down he came. While we were watching round her bed, She turned her eyes and looked away, She saw what we couldn't see; She saw Old Death. She saw Old Death Coming like a falling star. But Death didn't frighten Sister Caroline; He looked to her like a welcome friend. And she whispered to us: I'm going home, And she smiled and closed her eyes. And Death took her up like a baby, And she lay in his icy arms, But she didn't feel no chill. And death began to ride again-Up beyond the evening star, Into the glittering light of glory, On to the Great White Throne. And there he laid Sister Caroline On the loving breast of Jesus. And Jesus took his own hand and wiped away her tears, And he smoothed the furrows from her face, And the angels sang a little song, And Jesus rocked her in his arms, And kept a-saying: Take your rest, Take your rest. Weep not--weep not, She is not dead; She's resting in the bosom of Jesus. Tableau by Countee Cullen Locked arm in arm they cross the way The black boy and the white, The golden splendor of the day The sable pride of night. From lowered blinds the dark folk stare And here the fair folk talk, Indignant that these two should dare In unison to walk. Oblivious to look and word They pass, and see no wonder That lightning brilliant as a sword Should blaze the path of thunder. Incident by Countée Cullen Once riding in old Baltimore, Heart-filled, head-filled with glee; I saw a Baltimorean Keep looking straight at me. Now I was eight and very small, And he was no whit bigger, And so I smiled, but he poked out His tongue, and called me, "Nigger." I saw the whole of Balimore From May until December; Of all the things that happened there That's all that I remember. Some Harlem Renaissance Art The social and political anxieties that many African Americans felt just after World War I (1914-1918) were alleviated, in part, by mass migrations to the urban North. Northern cities offered a rest from the repressive attitudes and mandates of the old Southern order. The new racial compositions of cities like Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, New York, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago, and Saint Louis, in combination with a heightened social consciousness and a seemingly unbound desire for leisure and escapism, conspired to help create the cultural phenomenon known as the New Negro movement. Visual artists played a key role in creating depictions of the New Negro. Laura Wheeler Waring Still Life, 1929, oil on canvas. Palmer Hayden (American, 1890-1973), Nous Quatre a Paris (We Four in Paris), no date, watercolor on paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Palmer Hayden, Jeunesse, no date, watercolor on paper. Archibald J. Motley, Blues, 1929, oil on canvas. Aaron Douglas, Crucifixion, 1927, oil on canvas. Aaron Douglas, Rebirth, 1927, oil on canvas Augusta Savage Gamin, 1930, bronze Dox Thrash Railroad Yard, c. 1933-1934 Aaron Douglas, Study for Aspects of Negro Life: The Negro in an African Setting, 1934, gouache (gwahsh – heavy, flat watercolor paint) on Whatman artist’s board William H. Johnson, Chain Gang, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C. Loïs Mailou Jones Negro Shack I, Sedalia, North Carolina, 1930, watercolor on paper Jacob Lawrence, Pool Parlor, 1942, gouache on paper Harlem Renaissance set the tone for Civil Rights and Desegregation: Empowerment