A Few Notes on Once in a Lifetime By Terry Curtis Fox There has

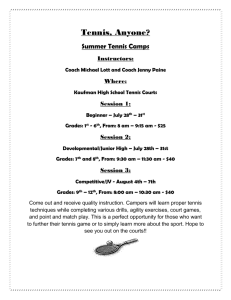

advertisement

A Few Notes on Once in a Lifetime By Terry Curtis Fox There has never been -- nor, it is safe to say, there will ever be -- another American playwright with quite the stature of George S. Kaufman. By 1930, when Once in a Lifetime opened on Broadway, Kaufman had, with an assortment of collaborators, written twenty plays. Among them were works that helped redefine American comedy, not to mention two musicals that pretty much defined the Marx Brothers. Two years previous, Kaufman had begun directing as well. His first outing was The Front Page, the Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur play that forever shattered the notion that farce belonged to the upper crust. In Once in a Lifetime, Kaufman became an actor as well. Eventually, he would transform himself into that peculiar thing, a television personality. (The TV gig was a result of Kaufman's deserved reputation as a ferocious wit, earned as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table.) And if that were not enough, he was also, until the play you're about to see, the drama editor and second-string theatre critic for the New York Times. (First string was Alexander Wollcott, on whom Kaufman and Hart would base Sheridan Whiteside, The Man Who Came to Dinner. As third string, Kaufman hired Herman Mankiewicz. Kaufman never wrote about “Mank” [the nickname stuck to every member of clan even remotely connected to the business], but he did fire him – when he found the drunken critic asleep at his desk with a half-finished pan in his typewriter. Mank would use that incident himself, when he wrote Citizen Kane.) Kaufman eventually left the Times, not because there was any perceived conflictof-interest but because he simply was too busy to stay in the job. In every one of these roles, Kaufman was universally respected. Among those who idolized him was Moss Hart. In part because of the collaborations with Kaufman that followed, Hart would obtain a good deal of celebrity himself. Kaufman referred to Hart as his "favorite collaborator," a pretty high encomium considering that among his other co-authors were Ring Lardner, Marc Connelly, and Edna Ferber. (For this and other biographical details, I am indebted to Howard Teichmann's George S. Kaufman, an Intimate Portrait.) Like his friend and mentor, Hart was first and foremost a man of the theatre, at a time when Broadway was at the center of American culture, both pop and serious. His writing would win him a Pulitzer (for another collaboration with Kaufman, You Can't Take It With You). In 1956, Hart directed the initial production of My Fair Lady, which many of us consider the single greatest production in the history of the American musical theatre. (Kaufman, of course, got there first. In 1950, he directed the first production of the greatest of all musicals, Guys and Dolls.) Ironically, Hart may be best remembered not for any of his plays or productions, but for a book -- his autobiography, Act One. Fully half of it is devoted to the genesis of Once in a Lifetime. The play began as a solo effort by Hart, who at the time was barely scratching out a living as a director of serious plays in "little theaters" (there was no real OffBroadway at the time) and as a tummler, a "social director" at Jewish resorts in the Catskills. Hart had grown up reading and attending Kaufman's plays. He considered the older man one of the few comedic playwrights worthy of attention and praise. When producer Sam Harris made it a condition for mounting the play that Hart collaborate with Kaufman, he swallowed his pride and prepared for life as an acolyte. The process was tortuous. I will not spoil the story (just read Act One; it is in our, and just about every other, library). Suffice to say that no playwright who has ever read it (and all of us have) can ever complain about rewriting. It is important to note that in 1930, talkies were only three years old. Unlike Singing in the Rain, which shares its subject matter, Once in a Lifetime was not written with the safety of nostalgia. When Jerry rushes in to say that he's seen the future at a movie called The Jazz Singer, he's talking about something that has just turned his -- and every other vaudevillian's -- world upside down. (In fact, the legend that it was The Jazz Singer alone that ended the silent era is just that, legend, as my friend and colleague Dave Kehr has demonstrated1. But it is undeniable that in the three years between the inspiration and production of the play, silent film had effectively vanished. Indeed, Alfred Hitchcock would reshoot his silent film Blackmail, delaying its release until 1929 so that it would have dialogue. The last great silent film, Carl Theodore Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc, was made in 1928.) Hart had no firsthand knowledge of the film business when he wrote the play; Kaufman had enough to make him loathe it. Both men understood that sound films would forever alter not just the movies, but Broadway. It's no accident that two scenes in the play occur in a railroad car. No one in 1930 jumped on a jet for a meeting. When it took three days to cross the country, “When Hollywood Learned to Dance and Sing” by Dave Kehr, New York Times 17 January 2010. http://topics.nytimes.com/topics/reference/timestopics/people/j/al_jolson/index. html 1 writers, actors, and directors had to declare themselves: either they were theatre people or movie people. (Among the group of aspiring theater practitioners with whom Hart regularly lunched was an about-to-be produced playwright named Preston Sturges. The success of his play took him to Los Angeles, from which he never returned.) Kaufman and Hart (as senior man, Kaufman got first billing) knew what this would mean for playwrights. Lawrence Vail, the fictional playwright, is a man virtually kidnapped by the film business. Kaufman first played the part on Broadway and then, in one of those can't-make-it-up moments, was destined to repeat the role in real life, when Irving Thalberg brought him out to the coast to write A Night at the Opera and kept him waiting for days in his waiting room. (When Thalberg finally deigned to talk to him, he wanted the screenplay immediately. Kaufman replied, "Do you want it Wednesday or good?" Writers have stolen the line ever since.) Although his wife Beatrice was an ardent New Deal Democrat, Kaufman himself seems to have had no politics. He was as comfortable collaborating with the liberal Hart as he was with the ultra-right wing Morrie Ryskind, with whom he wrote the Gershwin musical, Of Thee I Sing. Along with the nearly contemporaneous Show Boat, based on a novel by frequent Kaufman collaborator Edna Ferber, Of Thee I Sing revolutionized musicals' books. Before those shows, musicals (including the ones Kaufman wrote for the Marx Brothers) were essentially revues -- the books were quick jokes leading from one unrelated song to another. Of Thee I Sing not only had a story; it was about Presidential campaigns. Kaufman won his first Pulitzer for that show, the first time a musical had won the prize. The man who declared "satire is what closes on Saturday night," Kaufman had a newspaper man's cynicism -- ready to satirize the left and the right with equal fervor. Journalists see and know too much to put anyone on a pedestal, and this attitude infuses classic American comedy. As Teichmann persuasively demonstrates, Kaufman had only one cause: playwrights. It was the word he used to describe himself (never director or actor or journalist), and it was the role he, like Hart, most admired. He was a founding member of the Dramatists Guild, threatening to withhold his work if producers did not give playwrights complete contractual control of their work, and became its Vice-President. (Hart would later be President of the Guild.) Kaufman and Hart rightly saw that the writer would never achieve the same status in film as they had in the theatre. This was the basis for all the venom spewed forth in this play. And yet ... the need for dramatic writers was mandated by sound film. Playwrights, like the fictional Vail and the very real Kaufman and Hart, were the only people who knew how to write the movies that were now going to be made. The result is that film and stage comedy evolved together, in a very similar manner. The style, attitudes, and tone of Broadway and Hollywood were close to congruent. Samson Rafaelson, who wrote the play on which Jazz Singer was based, became sound film’s first great comedic screenwriter. (He would actually go back and take what he learned in L.A. to Broadway, one of the few to continue to work in both media.) Hart's erstwhile luncheon companion, Preston Sturges, would become the most important writer and director of screen comedies of all time, whose influence continues to this day in the work of writer/directors like Wes Anderson. And many of our great screen comedies are adaptations of Broadway comedies, including those of Ben Hecht (who flourished as a screenwriter) and Kaufman and Hart. (Kaufman refused to do any screen adaptations, ceding the task to Herman Mankiewicz; Hart would write a few screenplays on his own.) Indeed, if Once in a Lifetime were about anything other than the movies, it would have made a great film (as Kaufman and Ferber’s Royal Family of Broadway and Kaufman and Hart’s You Can’t Take It With You both did). “Screwball comedy” was not hatched whole in Hollywood: it was nurtured and developed on the Broadway stage. Setting out to skewer the movies at the beginning of the sound era, Kaufman and Hart inadvertently helped define it. Once in a Lifetime is nearly as notable as what it doesn’t contain as for what it does. Three things in particular stand out: The first thing to notice is that there are no jokes in the play. As a writer for the Marx Brothers, Kaufman certainly knew his way around a gag, as did the Catskilltrained Hart. But when writing this play, they avoided gags entirely. Instead, the human comes entirely out of the characters and the situations. (In order not to ruin your enjoyment of the performance, I’ll put what I’m talking about in a footnote. Read it at intermission or your leisure.2) 2 Take the line “the legitimate theatre had best look to its laurels.” By itself, the line has no humor whatsoever. Indeed, it’s quite possible that Hart (who read Variety as his research material) could have lifted it from a contemporary review of Jazz Singer. But when George says this line to Helen Hobart, it suddenly takes on comic life. The humor isn’t in the line – it’s the fact that George is telling it to a woman who bills herself as the Great Insider. His naiveté makes us laugh. That Helen takes this seriously, proclaiming George a genius, just makes things funnier. Add to this Mae’s rising panic – surely someone is going to remember where George stole this notion – and you have classically rising humor without a joke in sight. The other thing the play eschews is psychological motivation. The Group Theatre, which popularized Stanislavski’s “Method,” was not founded until 1931, a year after Once in a Lifetime opened. It’s not that the characters in this play lack motivation – it’s that theirs is outer and not inner directed. What drives Jerry and Mae is very direct and very directly a product of their times – hunger. (This is also what makes the play so terrifically relevant today.) One has to understand that in 1930, the United States was in the Great Depression but did not know it. The market had collapsed in 1929, but there are been other “panics” before. Recovery might be, as Republican President Herbert Hoover liked to believe, “just around the corner.” Hoover’s laissez-faire economic policies (identical to Mitt Romney’s in all but name) were to trust the market to correct itself. Today, a non-interventionist stand is a willful refusal to understand history. Then, it was a lack of clairvoyance. The only thing anyone knew in 1930 was that things were bad and that people – especially people like Mae, George, and Jerry – needed jobs. The alternative was dire. This play was produced two years before FDR ran for President. There was no social safety net. No Social Security, no unemployment insurance, no welfare. (It would take another thirty-five years before one would see Medicare or Medicaid.) Starvation and homelessness were real threats to anyone without a job. Kaufman knew what it was like to be broke. (Teichmann believes Kaufman kept his position at the Times long after he had begun writing hits because he was convinced that his money would disappear.) Hart knew what it was to be poor. For Hart, hunger was not metaphorical, any more than it is for Mae. George, the holy fool, can apparently exist on Indian Nuts. All he wants is to be a part of this group. Jerry wants what the play’s title promises – a shot at huge success (which, of course, means a lack of anxiety). Mae, the most knowing character in the play, is looking only slightly ahead. She wants a roof over her head and three square meals a day. The alternative is too awful to contemplate. This is what drives Mae and drives the play. Like Hart, Mae sees catastrophe just around the corner and is running as hard as she can to avoid it. People who are desperately hungry have little else on their minds, and this may explain the play’s oddest omission – its almost total lack of sex. The “Production Code,” which forced sex to be subverted in American films, was adopted the same year that Once in a Lifetime was produced, as much a product of the sound era as this play. While the play was being written, sex was very much on the mind of the movies – and the theatre. Hart’s pal Preston Sturges called it “Topic A.” Samson Rafaelson’s scripts, both pre- and post-code, are suffused with sex, as are those of his great successor, Billy Wilder (not to mention those by Ben Hecht and each of the brothers Mankiewicz). Kaufman was no stranger to sex – indeed, in a few years he would get yet another reason to hate the film industry when his long-term affair with Mary Astor (best remembered for her role in John Huston’s remake of The Maltese Falcon) was made shamelessly public once Astor’s husband sued for divorce. Astor kept a diary which while sedate in its language was as explicit as any current sex blog. For a while Kaufman was as famous for his philandering as he was for his writing. He had to flee California in a Keystone Cops style chase in order to avoid appearing in court. (In typical Kaufman fashion, he later became good friends with the judge who issued the bench warrant to compel his appearance at trial.) But despite the sales appeal and prevalence of sex in both film and the theatre, it’s not in this play at all. Mae may query whether Jerry is interested in her in “that way,” but it’s hardly what drives her. And while George certainly goes gaga once Susan appears, the attraction is nothing more than puppy-love on his part and ambition on hers. This is not a play that ends with a marriage. It’s a play that ends with a business deal. It’s also a play with a female protagonist. Jerry is a minor figure in the play. George, being a holy fool, cannot move the action. His decisions have consequences, but they are determined by some invisible hand, not his own. Mae, on the other, is responsible for every consequential action in the play. It’s she who comes up with the idea of the elocution school, she who involves Helen Hobart, she who chooses to return to L.A. rather than continue to New York in the end. She is first and foremost a professional woman at a time when that was a rarity and not the norm. While the Kaufmans’ marriage was, to put it mildly, unconventional, the couple was devoted to each other. Beatrice Kaufman was an editor; George collaborated with Edna Ferber and was, for a while, among Dorothy Parker’s closest friends. At the time of writing, Hart was single – but when he did marry, it was to the actress Kitty Carlisle, among the theatre’s most forceful women. (She would eventually become chair of the New York State Council on the Arts.) Neither Kaufman nor Hart were afraid of strong women, and, in Mae, they would put one center stage. She is simply too driven by hunger and by the need to keep her head afloat to let her romantic desire rule her actions. What the play does have are many, many contemporaneous references. This was a play for its time. No one involved imagined that it might possibly be one for ours. Kaufman and Hart may have believed that the theatre was a far superior medium than film, but they regarded themselves as craftsmen, not artists. Once in a Lifetime was very much conceived and executed as a commercial venture – in this regard, as well, utterly in keeping with way in which the real-life Lawrence Vails approached their scripts. Kaufman and Hart were not writing for the ages – they were looking for a hit. They got their desire – the play was a huge success and cemented a collaboration that would produce many more. As it turned out, Once in a Lifetime is one of those achievements that transcends its origins. Eighty-two years after its opening – when Hedda Hopper, the actual brothers named Warner, and Vitaphone are historical footnotes -- the play remains as vibrant as ever, a shining example of American comic art.