Photographic Adventure

advertisement

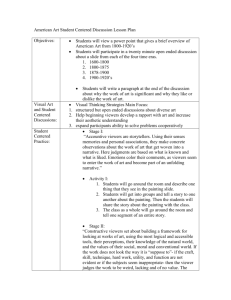

Shi1 Assignment #2: Analysis: Theory and Practice Jiacheng Shi Professor Berkley English 125 March 1, 2014 Photographic Adventure We are living in a world separated by time and space, but photographs overcome the vastness in geographic space by providing us with an extended visual world. It is no longer a fantasy to experience the other side of the world without the great cost of time, effort, and money. Just staring at a photograph, we can wander into a great adventure in the photographic world. In Barthes’s “Camera Lucida”, the author analyzes the essential attraction of photography. He claims that “the best word to designate (temporarily) the attraction certain photographs exerted upon me was advenience or even adventure”(19). Adventure, as its name suggests, is a journey that begins with a main purpose and shines with accidental encounters. James Mollison, a contemporary documentary photographer, shows a series of “adventures” in his work, Where Children Sleep, published in 2010. The theme of the photo sets engages with children’s rights associated with children’s different lives. Instead of depicting children directly, Mollison focuses on their bedrooms to reveal their true lives. Taken from different countries and with diverse backgrounds, these photos Shi2 depict children’s totally distinctive living conditions throughout the world. Each photograph just shows an image with a simple children’s bedroom. But the static image turns out vivid and replete with meaning. In Camera Lucida, Barthes demonstrates the “adventure” a step further: “In this glum desert, suddenly a specific photograph reaches me; it animates me, and I animate it. So that is how I must name the attraction which makes it exist: an animation. The photograph itself is in no way animated (I do not believe in “lifelike” photographs), but it animates me: this is what creates every adventure.” (20) The place children sleep indeed epitomizes most aspects of their lives. The images of bedrooms are not “lifelike”, though, but they undoubtedly animate the viewers. And this series of photographs, in itself, can bring people into an adventure to see different lives throughout the world. With sunlight percolating through the tent-like dome of Nantio’s house, we are brought to the Rendille tribe in northern Kenya. (Mollison 109) I actually feel as if stepping into a fairy tale world at the first glance. Everything seems wonderful and teems with mystery. In the staggered lights and shadows, however, an unimaginably poor child’s life rises. No paved floor below and no firm ceiling ahead, Nantio has been in such a primitive lifestyle since she was young. Rather than the temporarily wonderful lights and shadows, we can imagine rains penetrating the dome and nights swallowing the Shi3 whole bedroom. The adventure does not necessarily come to a romantic ending, but it can be impressive enough. In this regard, to approach “a specific photograph” is to embark on an adventure. Here comes the essential question. What makes the “specific photograph” in Barthes’s claim? What animates Mollison’s photographs? What, on earth, creates the adventure in the photographic world? In Camera Lucida, Barthes emphasizes two different themes, “studium” and “punctum”, which from his perspective make the two core elements to provide adventure of photography. And these elements are illustrated in Where Children Sleep. Studium is an extension for the photograph. It shouts out a photo’s theme, background, and whatever the operator intentionally conveys. It involves “a kind of general, enthusiastic commitment… but without special acuity” (Barthes 26). In order to create hints for viewers to follow, photographs should be effectively tied with the operator’s main idea. In Where Children Sleep, Mollison applies a direct and succinct method to capture his viewers. He describes the stories of children with captions attached to each photograph. From the captions, viewers acquire sufficient information behind the pictures, and in the mean time, they go a step closer to the theme. Going back to Mollison’s depiction of Nantio’s bedroom, we can see Mollison accesses his viewers by such a passage: “Nantio, 15, is a member of the Rendille tribe in northern Kenya. She has two brothers and two sisters. Her home is a tent-like dome made from cattle hide and Shi4 plastic, with little room to stand. There is a fire in the middle, around which the family sleep. Nantio’s chores include looking after the goats, chopping firewood and fetching water. She went to the village school for a few years but decided not to continue. Nantio is hoping a moran (warrior) will select her for marriage. She has a boyfriend now, but it is not unusual for a Rendille woman to have several boyfriends before marriage. First, she will have to undergo circumcision, as is the custom” (109). Viewers easily get to know about the bedroom owner’s experience, hardship, and background. Moreover, it points out some details, such as “dome made from cattle hide and plastic”, “little room to stand”, which emphasizes what Mollison focuses on when he constructs the picture. To put it another way, at least this is what he wants viewers to focus on more. It is necessary to show this focus directly and the caption works effectively. Viewers can pay attention to the poor condition of the bedroom rather than the beauty of the primitive nature. Barthes thinks that, “to recognize the studium is inevitably to encounter the photographer’s intentions”(27). If Mollison does not shout his voice out, viewers will probably stop by the aesthetic aspects of his photographs and have difficulty gaining insights into them. By showing the stories of photographs, Mollison leads his viewers to better understand his intention and think about the children’s rights. Moreover, not only the captions lead people to his theme, but the objects included in his photographs do as well. Mollison focuses on both bedrooms and children’s facial portraits, which are the most common things that can be understandable. He expresses his thoughts in the interview: “the idea was that on the plain background you would be treating the kids equally, and then their bedrooms would talk about their situation.” (Hammer) To depict children’s lives, each bedroom is distinctive. However, “the diversity Shi5 also provides a sense of togetherness”. (Macdonald) To convey the central idea of the photographs, every face is similar. With the same indifferent expression on children’s faces, the photos easily reach viewers’ feelings and provoke whatever all human beings share. Viewers therefore begin wandering in the brain world that has been extended by the photo. They think about children’s lives, and then discover the inequality Mollison wants to convey. In this regard, both the captions and objects in Where Children Sleep, in this way, function as Mollison’s studium, which accentuates his theme and intention. Without the studium, the adventure is vague and devoid of significance. While studium avoids duality, indirection, and disturbance of the adventure, it still lacks of the animation without a certain shock. Barthes defines the kind of shock as punctum. To explain the term punctum, he clarifies that, “this time it is not I who seek it out; it is this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me.” However, punctum must lie on a personal level to be impressive and striking enough. Viewers often discover it accidently. It seems difficult for a photographer to actively involve punctum in his photographs. In another word, it is almost impossible to create it intentionally. The reason is that punctum comes out of the photos by accident and whether it pricks viewers differs from every individual. But in Where Children Sleep, Mollison achieves this striking effect as punctum in his own way. His typological photographic style emphasizes strong comparison. By comparing his photos one another, viewers find their personal shocks penetrating out from the photographs on the surface. Shi6 Mollison comments on his own project, “you are letting people compare so it tells a larger story.” (Perfect Picture) For example, the comparison of two kids’ bedrooms both from Manhattan, New York, can strike different viewers in diverse ways. From their bedrooms with sufficient toys and clothes, we can see that both Schuyler and Tristan are living above the average standard. But viewers could also see different things through them. Poor people may still easily recognize obviously distinctive living conditions between two children. They could focus on the broken roof of Schuyler’s bedrooms and be totally absorbed with the gold dragon bird decoration on the ceiling of Tristan’s bedrooms. Busy and tired people may zoom into toy cars in the first bedroom and realize Schuyler has a relaxing and happy life; however, in the second bedroom, they may be thrilled by the bookshelf full of books and think Tristan must be as busy as themselves to read so many books. By comparison, viewers obtain the opportunity to infuse their own experience to the interpretation of the photograph and eventually find their personal punctum. Punctum accidentally comes out just because the photograph truly resonates with viewers’ own experience. Besides Mollison’s comparative style, he doesn’t intentionally add any more hints to his picture to disturb viewers’ interpretation. He just puts his photographs together and allows viewers to compare them. In fact, the adventure of photographs is created in two steps. The operator plays the first step. Mollison accentuates his intention and powerfully conveys his theme. And Shi7 the spectators play the second step. The operator cannot intentionally intervene this process. But from Mollison’s comparative style, spectaculars can easily find their own personal shocks. Barthes claims about the photography that, “its ‘adventure’ derived from the co-presence of two discontinuous elements”. In Where Children Sleep, Mollison takes Barthes’s claim a step further that he does not only show both sides but also find a perfect balance between studium and punctum, which are not discontinuous and function together to construct his adventure. Works Cited Shi8 Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections On Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981. Karla Hammer, SHOW AND TELL, Eye Magazine Online http://www.eyemaga zine.com/feature/article/show-and-tell, Winter 2012. Kerry Macdonald, ‘WHERE CHILDREN SLEEP’, New York Times Online, http: //lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/04/where-children-sleep/?_php=true&_type=blogs &_r=0, August 4, 2011. Mollison, James. Where Children Sleep. London: Chris Boot, 2010. Mollison, James, Perfect Picture, Online video, http://www.youtube.com/watc h?v=YXcGcy9vrqc, 2013