The Scarlet Letter - English-UniSbg

advertisement

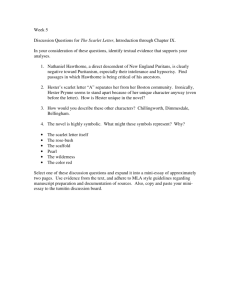

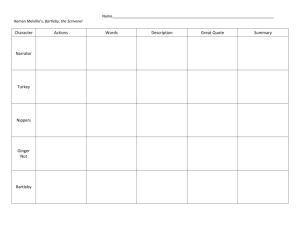

Fachbereich Anglistik Sommersemester 2009 History of American Literature Prof. Dr. Ralph J. Poole Transcendentalism and Romanticism • Essay: Ralph Waldo Emerson. "Nature"; "The American Scholar" Henry David Thoreau, Walden, or Life in the Woods Margaret Fuller. Woman in the Nineteenth Century • Poetry: Walt Whitman. Leaves of Grass: "Song of Myself“ Emily Dickinson. (poems) • Short Story and Novel: Nathaniel Hawthorne. "Young Goodman Brown", The Scarlet Letter Edgar Allan Poe. "The Fall of the House of Usher" Herman Melville. Moby-Dick, "Bartleby the Scrivener" Imagining Disaster: Dark Romanticism • • • • • • • • Poe, Hawthorne, Melville, Dickinson Reaction to Transcendentalism Pessimistic outlook on mankind, nature, God Individual prone to sin and self-destruction Anthropomorphized evil: devil, ghost, vampire Nature reveals evil, decay, dark mystery Anti-social tendency: man as failure Relation to Gothic fiction (terror, supernatural, melodrama) Nathaniel Hawthorne • • • • First associated with, then distanced from Transcendentalism Troubled heritage of Puritanism The Scarlet Letter (1850) The House of the Seven Gables (1851) (historical romance, set in 19th century New England mansion haunted by 17th cent. Puritan witchcraft accusations) • The Blithedale Romance (1852) (based on Hawthorne's recollections of Brook Farm, romance ending in tragedy) • The Marble Faun (1860) (unusual romance, written shortly before Civil War, novel is set in a fantastical Italy, mixture of pastoral, gothic, and travel guide) Hawthorne: Narrative Method • • • • Detached point of view Elevated diction, polished perfection, restrained rhetoric Limited number of themes and character types (Puritan past) Limited number of situations: moral problems with ambiguous resolutions (sin/guilt as part of life, concealment or confession: death or redemption; manipulating another person’s soul unforgivable) • Allegory and symbol psychological depth, universally human, not didactic or religious • Customs and morals (history) shape collective unconscious Novel vs. Romance "WHEN a writer calls his work a Romance, it need hardly be observed that he wishes to claim a certain latitude, both as to its fashion and material, which he would not have felt himself entitled to assume had he professed to be writing a Novel. The latter form of composition is presumed to aim at a very minute fidelity, not merely to the possible, but to the probable and ordinary course of man's experience. The former-while, as a work of art, it must rigidly subject itself to laws, and while it sins unpardonably so far as it may swerve aside from the truth of the human heart-has fairly a right to present that truth under circumstances, to a great extent, of the writer's own choosing or creation. If he think fit, also, he may so manage his atmospherical medium as to bring out or mellow the lights and deepen and enrich the shadows of the picture. He will be wise, no doubt, to make a very moderate use of the privileges here stated, and, especially, to mingle the Marvelous rather as a slight, delicate, and evanescent flavor, than as any portion of the actual substance of the dish offered to the public. He can hardly be said, however, to commit a literary crime even if he disregard this caution." Nathaniel Hawthorne, Preface to 'The House of Seven Gables' Romance as Allegory The author’s moral to show the truth “that the wrong-doing of one generation lives into the successive ones, and, divesting itself of every temporary advantage, becomes a pure and uncontrollable mischief” (Preface) The Scarlet Letter, 1850 “If the truth were everywhere to be shown, a scarlet letter would blaze forth from many another bosom.” Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter, 1893. No. 1 in the "Arm Chair Library" series, which published cheap "Dime novels" weekly, then monthly, one novel per issue. The Scarlet Letter, 1850 “A” Literal: Adultery Allegorical: America Apocalypse Angel Art • The Scarlet Letter, T. H. Matteson, 1860 Edgar Allan Poe • European influences • “l’art pour l’art” • Short form as ideal: – – – – – Gothic tales Detective stories Poetry Essays Criticism • Only complete novel: The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket 1838 Creative Method: “wow”-effect and beautiful dead women “The Philosophy of Composition” 1846 • “If any literary work is too long to be read at one sitting, we must be content to dispense with the immensely important effect derivable from unity of impression- for, if two sittings be required, the affairs of the world interfere, and everything like totality is at once destroyed. […] • I asked myself- "Of all melancholy topics what, according to the universal understanding of mankind, is the most melancholy?" Death, was the obvious reply. "And when," I said, "is this most melancholy of topics most poetical?" From what I have already explained at some length the answer here also is obvious- "When it most closely allies itself to Beauty: the death then of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world, and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover." “The Fall of the House of Usher”, 1839 • Tales of the Grotesques and Arabesques – Grotesque: deformation, irrationality, fantastic – Arabesque: decors, exoticism, aesthetics • Sublime: aesthetic experience between spiritual elevation (rational) and fatal destruction (irrational), garden vs. wilderness, order vs. chaos • See Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, 1757 • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ugipBxA8zcg Aubrey Beardsley, 1894 “During the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country; and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher. I know not how it was--but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment, with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. I looked upon the scene before me--upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain--upon the bleak walls--upon the vacant eye-like windows--upon a few rank sedges--and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees--with an utter depression of soul which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveler upon opium--the bitter lapse into everyday life--the hideous dropping off of the veil. There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart--an unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime.” (“Usher”) “As if in the superhuman energy of his utterance there had been found the potency of a spell--the huge antique panels to which the speaker pointed, threw slowly back, upon the instant, their ponderous and ebony jaws. It was the work of the rushing gust--but then without those doors there DID stand the lofty and enshrouded figure of the lady Madeline of Usher. There was blood upon her white robes, and the evidence of some bitter struggle upon every portion of her emaciated frame. For a moment she remained trembling and reeling to and fro upon the threshold,-- then, with a low moaning cry, fell heavily inward upon the person of her brother, and in her violent and now final deathagonies, bore him to the floor a corpse, and a victim to the terrors he had anticipated. From that chamber, and from that mansion, I fled aghast. The storm was still abroad in all its wrath as I found myself crossing the old causeway. Suddenly there shot along the path a wild light, and I turned to see whence a gleam so unusual could have issued; for the vast house and its shadows were alone behind me. The radiance was that of the full, setting, and blood-red moon which now shone vividly through that once barely-discernible fissure of which I have before spoken as extending from the roof of the building, in a zigzag direction, to the base. While I gazed, this fissure rapidly widened--there came a fierce breath of the whirlwind-the entire orb of the satellite burst at once upon my sight--my brain reeled as I saw the mighty walls rushing asunder-there was a long tumultuous shouting sound like the voice of a thousand waters-and the deep and dank tarn at my feet closed sullenly and silently over the fragments of the "House of Usher".” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GRImdHb3woo&feature=related Herman Melville • initial success with Typee (1846) • Moby Dick (1851): no success • neglected during lifetime • revival 1924 publication of Billy Budd Melville: Writing Themes • preeminence of democracy • nobility of labor and common man • ubiquity of evil • danger of merging the personality in the cosmic ‘all’ • need to balance transcendental insight with empirical ‘truth’ • hubris of seeking in nature ultimate answers to metaphysical questions • impossibility of man’s returning to his original innocence • life as pathetic and greedy Narrative methods: • elevated, formal style • rhetorical flourishes, highly literary • allusions to literature, history, theology, philosophy, science • mostly symbolic, often parabolic and allegorical • complex, ambiguous symbols • aesthetic, intellectual appeal Melville: Works • Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846) – fictionalized biography (“the man who lived amongst cannibals”) – benevolent captivity by a tribe of pleasure-loving Marquesan “cannibals” – young Tommo’s (Melville’s alter ego’s) discovery: civilized man cannot return to paradise – critique on American (and French) colonialism / imperialism – ethnography and literature Excerpts from Typee Critique of Colonialism: Fear of Cannibalism: • • Our ship was now wholly given up to every species of riot and debauchery. Not the feeblest barrier was interposed between the unholy passions of the crew and their unlimited gratification. The grossest licentiousness and the most shameful inebriety prevailed, with occasional and but short-lived interruptions, through the whole period of her stay. Alas for the poor savages when exposed to the influence of these polluting examples! Unsophisticated and confiding, they are easily led into every vice, and humanity weeps over the ruin thus remorselessly inflicted upon them by their European civilizers. Thrice happy are they who, inhabiting some yet undiscovered island in the midst of the ocean, have never been brought into contaminating contact with the white man. – Chapter II • • ‘Hurra, my lads! It’s a settled thing; next week we shape our course to the Marquesas!’ The Marquesas! What strange visions of outlandish things does the very name spirit up! Naked houris—cannibal banquets—groves of cocoanut— coral reefs—tattooed chiefs—and bamboo temples; sunny valleys planted with bread- fruit-trees—carved canoes dancing on the flashing blue waters—savage woodlands guarded by horrible idols—heathenish rites and human sacrifices. – Chapter I Typee or Happar? I asked within myself. I started, for at the same moment this identical question was asked by the strange being before me. I turned to Toby; the flickering light of a native taper showed me his countenance pale with trepidation at this fatal question. I paused for a second, and I know not by what impulse it was that I answered "Typee." The piece of dusky statuary nodded in approval, and then murmured "Motarkee?" "Motarkee," said I, without further hesitation -- "Typee mortarkee." --Chapter X As the vessel had been placed in its present position since my last visit, I at once concluded that it must have some connection with the recent festival; and, prompted by a curiosity I could not repress, in passing it I raised one end of the cover; at the same moment the chiefs, perceiving my design, loudly ejaculated, "Taboo! taboo!" But the slight glimpse sufficed; my eyes fell upon the disordered members of a human skeleton, the bones still fresh with moisture, and with particles of flesh clinging to them here and there! -Chapter XXXII Moby Dick, or, the Whale (1851) • • • • • • common sailor “Ishmael” tells with realistic detail story of his symbolic voyage on board a whaler Pequod: polyglot crew (red, black, yellow, brown) under command of Captain Ahab = Ship of the World, manly utopia Ahab’s goal: to discover in white whale the ultimate force governing the cosmos; hubris Ahab’s demise: mad presumption of quest ends in catastrophe (all but Ishmael drown, Pequod sinks) Moby Dick (nature as creative, destructive and inextinguishable) remains victorious romance quest (hybrid form, literary experiment, allegory) Beginning of Moby Dick • Call me Ishmael. Some years ago--never mind how long precisely--having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people's hats off--then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me. “Bartleby the Scrivener A Story of Wall-Street” (1853) • Piazza Tales (1856) • humor and pathos • despair: iron necessities of pathetic life (copyist (“dead letters”, not “belles lettres”) = anti-artist) • Bartleby: isolation, autism • provoking passivity and maddening non-compliance (“I would prefer not to”) death • teaching complacent employer to embrace commandment to love fellow man • unreliable narrator (employer) Excerpts from “Bartleby” • I am a rather elderly man. The nature of my avocations for the last thirty years has brought me into more than ordinary contact with what would seem an interesting and somewhat singular set of men, of whom as yet nothing that I know of has ever been written:--I mean the law-copyists or scriveners. I have known very many of them, professionally and privately, and if I pleased, could relate divers histories, at which good-natured gentlemen might smile, and sentimental souls might weep. But I waive the biographies of all other scriveners for a few passages in the life of Bartleby, who was a scrivener of the strangest I ever saw or heard of. While of other law-copyists I might write the complete life, of Bartleby nothing of that sort can be done. I believe that no materials exist for a full and satisfactory biography of this man. It is an irreparable loss to literature. Bartleby was one of those beings of whom nothing is ascertainable, except from the original sources, and in his case those are very small. What my own astonished eyes saw of Bartleby, _that_ is all I know of him, except, indeed, one vague report which will appear in the sequel. • In this very attitude did I sit when I called to him, rapidly stating what it was I wanted him to do--namely, to examine a small paper with me. Imagine my surprise, nay, my consternation, when without moving from his privacy, Bartleby in a singularly mild, firm voice, replied, "I would prefer not to." I sat awhile in perfect silence, rallying my stunned faculties. Immediately it occurred to me that my ears had deceived me, or Bartleby had entirely misunderstood my meaning. I repeated my request in the clearest tone I could assume. But in quite as clear a one came the previous reply, "I would prefer not to." "Prefer not to," echoed I, rising in high excitement, and crossing the room with a stride. "What do you mean? Are you moonstruck? I want you to help me compare this sheet here--take it," and I thrust it towards him. "I would prefer not to," said he. Billy Budd, Sailor (1924) • conflict between Billy Budd’s Christ-like innocence and John Claggart’s evilness • resolution with godlike reason by Captain Vere • crucifixion imagery: Billy’s execution on the cross of the mainmast • best-known adaptation: opera by Benjamin Britten with libretto by E. M. Forster and Eric Crozier (1951) • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rt6nWzcgj4k&feature=related Excerpt from Billy Budd It was noted at the time and remarked upon afterwards, that in this final scene the good man evinced little or nothing of the perfunctory. Brief speech indeed he had with the condemned one, but the genuine Gospel was less on his tongue than in his aspect and manner towards him. The final preparations personal to the latter being speedily brought to an end by two boatswain's mates, the consummation impended. Billy stood facing aft. At the penultimate moment, his words, his only ones, words wholly unobstructed in the utterance were these--"God bless Captain Vere!" Syllables so unanticipated coming from one with the ignominious hemp about his neck-a conventional felon's benediction directed aft towards the quarters of honor; syllables too delivered in the clear melody of a singing-bird on the point of launching from the twig, had a phenomenal effect, not unenhanced by the rare personal beauty of the young sailor spiritualized now thro' late experiences so poignantly profound. Without volition as it were, as if indeed the ship's populace were but the vehicles of some vocal current electric, with one voice from alow and aloft came a resonant sympathetic echo-"God bless Captain Vere!" And yet at that instant Billy alone must have been in their hearts, even as he was in their eyes. At the pronounced words and the spontaneous echo that voluminously rebounded them, Captain Vere, either thro' stoic self-control or a sort of momentary paralysis induced by emotional shock, stood erectly rigid as a musket in the ship-armorer's rack. The hull deliberately recovering from the periodic roll to leeward was just regaining an even keel, when the last signal, a preconcerted dumb one, was given. At the same moment it chanced that the vapory fleece hanging low in the East, was shot thro' with a soft glory as of the fleece of the Lamb of God seen in mystical vision, and simultaneously therewith, watched by the wedged mass of upturned faces, Billy ascended; and, ascending, took the full rose of the dawn.