View/Open

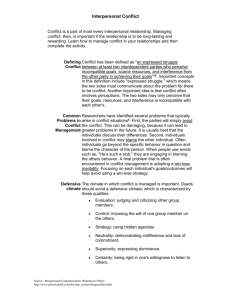

advertisement