powerpoint

advertisement

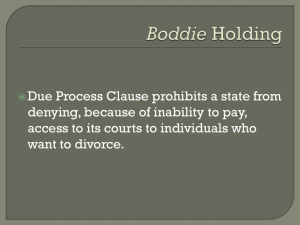

Boddie v. Connecticut 401 U.S. 371 (1970) Jessica Galant Elizabeth Monterrosa Introduction Access to the courts is a fundamental right in the United States, protecting procedural due process guarantees under the Due Process Clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments. The many fees imposed on filing a court case can encumber the constitutional right to litigate. Even insignificant fees can bar an indigent litigant from going to court because such fees caused substantial economic burden on indigent households. The Cost of Divorce in Connecticut Conn. Gen. Stat. § 52-259: “There shall be paid to the clerks of the supreme court of errors or the superior court, for entering each civil case, twenty-two dollars…” Modified by Public Act 628: “There shall be to the clerks of the supreme court or the superior court, for entering each civil case, forty-five dollars…” Service of Process Fee: Divorce Judgments, whether for the plaintiff or the defendant, not including judgments annulling a marriage, fifty dollars to be charged in all cases against the plaintiff… Sheriff’s service fee=Minimum of $10-$15 Publication=$100 in Hartford and $150 in NYC Total=a minimum of $60 for a divorce http://www.uncontested.ca/ Historical Context Prior to Boddie, the Supreme Court addressed obstruction to access to the courts for criminal indigent defendants. The Griffin v. Illinois case held that an indigent litigant must be afforded a transcript for a criminal appeal. Griffin established the constitutional imperative that the quality of one’s trial cannot depend on how much money one makes. However, the decision limited the right to access to the courts via fee waivers to criminal appeals. Historical Context, cont. Federal funding became available under the Economic Opportunity Act of 1966 and many legal services programs sprouted into existence: E.g. New Haven Legal Assistance Association Legal services programs nation-wide embraced and promoted a fundamental value for adjudication as the alternative to self-help in American society. Public interest advocates seeking law reform via litigation brought and argued an unprecedented number of cases before the Supreme Court. Historical Context, cont. §1983 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 emerged from dormancy in the 1961 Monroe v. Pape Supreme Court case. Provided a civil action for deprivation of rights. Granted private litigants a federal court remedy to inadequate state remedies. After Monroe, §1983 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 played a pivotal role in Fourteenth Amendment claims of due process violations. Only 10 years after the Monroe decision, the case provided the Boddie appellants with a new means, federal litigation, to seek law reform. The Boddie Parties: Ms. Gladys Boddie Served as the named plaintiff in Boddie. As a mother on welfare and in public housing, a free attorney at New Haven Legal Assistance Association provided her only option to obtain the divorce she sought. Lasted the entire four year case as a named plaintiff in Boddie. Today resides in Florida Two daughters are nurses One son is a federal judge One son is an attorney, pursuing a judgeship The Boddie Attorney: Arthur B. LaFrance After working as a criminal specialist for New Haven Legal Assistance Association, LaFrance found the plaintiffs while managing the association Today is a professor of law at Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon Specializes in criminal law and procedure; bioethics; health delivery systems; and poverty, health, and the law. Also engages in pro bono public interest litigation concerning healthcare issues http://www.lclark.edu/dept/lawadmss/lafrance.html Launching Boddie While managing the New Haven Legal Assistance Association, LaFrance encountered forty open divorce cases. Upon contacting the plaintiffs, LaFrance discovered they were unable to proceed with their divorces because they could not afford the filing fees. As the architect behind Boddie, LaFrance embarked on the difficult process of selecting plaintiffs and defendants, and bringing Boddie from the state district court to the Supreme Court in a valiant effort to transform the law for indigent civil plaintiffs: Launched a class action lawsuit to expand fee waivers from the criminal to the civil realm, specifically in divorce cases. Finding the Plaintiffs LaFrance sought: Indigent plaintiffs because court costs most often impede indigent plaintiffs’ efforts to commence civil litigation. African-American plaintiffs to highlight that access to justice often proves to be a racial issue. Non-contested divorces where the grounds for divorce and the indigent’s interest for divorce had persisted for several months due to their inability to pay initial filing fees because: Such cases demonstrated the need for law reform for indigent plaintiffs seeking divorce adjudication via the only available means, lengthy litigation proceedings, and ensured that the class action stood on strong cases that could endure the long judicial process. A class action case so that any member of the class could take advantage of the judgment and the ensure the preservation of the case over the many years of the litigation. Finding the Defendants Faced problems of sovereign and judicial immunity. Sued: The court clerk who initially denied the fee waiver. 2 Judges, including the judge who claimed he could not overrule the court clerk who refused to accept the fee waiver that LaFrance tried to file for his plaintiffs. Not excluded for judicial immunity because the case involved an administrative, rather than a judicial attack. The State of Connecticut Excluded due to 11th Amendment sovereign immunity. State Court Decisions Plaintiffs filed an application, financial affidavits, and divorce papers asking the Superior Court for New Haven County to waive filing fees and effect service of process. The clerk declined to file the papers without payment of fees. Superior Court Judge Joseph S. Longo declined to hear the motion to waive costs and effect service of process claiming that he did not have statutory authority to grant the relief sought. The Court Administrator for Connecticut, Supreme Court Justice John P. Cotter, took the same position as Judge Longo. http://www.dochertyfamily.com/ct_flag.htm Federal Court As the Plaintiffs were precluded state relief, LaFrance brought a civil rights action in the US District Court for the District of Connecticut Plaintiffs sought declaratory and injunctive relief. Claim: Connecticut violated Plaintiffs’ constitutional rights of equal protection of the laws and due process of laws by barring them from the courts solely on the basis of poverty. The U.S. District Court Decision 286 F.Supp. 968 Holding: Distinguished Griffin, a criminal case: There are “differences” between the right to freedom and the right to access to the court. Found that the State has two legitimate bases for imposing court fees: “A state may limit access to its civil courts and divorce courts” via required “filing fee or other fees which effectively bar persons on relief from commencing actions therein.” Such State-mandated filing fees do not offend the Equal Protection or Due Process Clauses of the 14th Amendment. 1. Providing financial support for the court establishment 2. Discouraging frivolous lawsuits Deferred to the state legislature to decide the political issue. Appellants’ Arguments The court costs of a divorce proceeding are a substantial barrier to litigation. These indigent appellants are barred from Connecticut courts by their inability to pay court costs. Appellants were denied equal protection of the laws when they were denied access to the courts solely because of their poverty. Appellants were denied due process of laws when they were denied the opportunity to petition for redress of grievances. Connecticut’s requirement that these indigent appellants pay court costs which they cannot afford is not a permissible exercise of the police power. The relief sought by appellants could properly have been rendered by the court below. Appellees’ Arguments Regulation of entry fees for the Connecticut Superior Court is within the exclusive domain of the Connecticut Legislature. The Griffin doctrine should be limited to cases concerning the personal liberty of an accused. The prepayment of court entry fees required by Connecticut General Statutes Sec. 52-259 is a Constitutional exercise of sovereign power. The Court should maintain the traditional concept that civil litigants are responsible for the costs incidental to bringing a legal action. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution only protects rights that are constitutionally guaranteed. Boddie, The Supreme Court Decision 401 U.S. 371 Reversed the District Court judgment below 8-1. Justice Harlan delivered the Opinion Holding: Filing fee requirements for divorce proceedings are unconstitutional. Noting the “fundamental” nature of the marriage relationship, such fees as applied to indigent plaintiffs violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because it denied access to the judicial process: “Given the basic position of the marriage relationship in this society’s hierarchy of values and the concomitant state monopolization of the means for legally dissolving this relationship, due process does prohibit a State from denying, solely because of inability to pay, access to its courts to individuals who seek judicial dissolution of their marriages.” The Court expanded the Griffin holding to the civil filing fee case at hand. Boddie Reasoning The Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment requires that a State afford all individuals a meaningful opportunity to be heard in the judicial process A facially-valid cost requirement offended due process because it impeded individuals’ opportunity to be heard when applied to indigents because the judicial proceedings serve as the only effective means of resolving the dispute in divorce. Boddie Reasoning, cont. Therefore, given the fundamental right to marriage, a State may not “pre-empt the right to dissolve this legal relationship without affording all citizens access to the means it has prescribed for doing so.” Because the judicial proceedings serve “as the only effective means of resolving the dispute,” a State cannot constitutionally deny indigent plaintiffs access to the courts via filing fees in divorce proceedings. Justice Douglas’s Concurrence Found that indigent divorce plaintiffs fell within a protected class under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment Therefore, the Equal Protection Clause would more properly shield indigent divorce plaintiffs from required filing fees and other fees. Justice Brennan’s Concurrence A State’s fee requirement as applied to indigent plaintiffs in any civil case makes a “mockery” of the Equal Protection principle by denying access to the judicial process. Justice Black’s Sole Dissent Found no basis for expanding criminal fee waivers from criminal defendants mandated to appear before the court to civil plaintiffs in divorce cases under either the Due Process or Equal Protection Clauses of the 14th Amendment. Effects of Boddie: Parties and Attorney The Plaintiffs generally: Because litigation spanned three to four years, the holding had only an inconsequential effect on the plaintiffs. However, it pleased all plaintiffs that they had played a pivotal role in changing the law for future divorce litigants. Out of the nine plaintiffs, only two remained until the Supreme Court handed down the Boddie decision. The seven others had found ways to get the filing fee money and proceed with their divorce cases. Effects of Boddie: Parties and Attorney, Cont. Ms. Gladys Boddie Boddie finally received her long-sought divorce. However, by the time of the judicial victory, Boddie had to pay the divorce filing fee because she was working as a nurse’s aid and did not qualify for the fee waiver. Unfortunately, Ms. Boddie did not understand the significance of the case until her son attended law school and encountered the case and playful bantering from fellow law students. Effects of Boddie: Parties and Attorney, Cont. The Boddie Legacy, Mr. Reginald Boddie Mr. Boddie’s desire to engage in public interest law stems from his mother’s mission against injustice and the dilapidated public housing conditions that the family endured during the time of the Boddie case. Although the legal community credits Ms. Boddie for her participation in the landmark divorce fee waiver case, the local New Haven community remembers Ms. Boddie for her tenant advocacy. While Mr. Boddie does not credit his mother’s participation in Boddie as the catalyst for his legal advocacy, he credits his mother for instilling a sense of social consciousness and responsibility within each of her children. Effects of Boddie: Parties and Attorney, Cont. The Boddie Legacy, Mr. Reginald Boddie, cont. Following in his mother’s footsteps, Mr. Boddie has accumulated an impressive track-record in the public interest legal services community. Boddie attended Northeastern University School of Law, a public interest law school, and has dedicated his career to the public interest generally. Boddie has worked at legal assistance organizations, where he initially focused on low-income housing issues and policy and then expanded into civil rights. Interestingly, Boddie worked for New Haven Legal Assistance Association prior to and during law school. He worked in the office's Housing Unit for two summers while attending Brown University and in the Criminal Law Unit for at least three quarters in law school. Effects of Boddie: Parties and Attorney, Cont. Attorney Arthur B. LaFrance Effect of Boddie on LaFrance has been personally satisfying because he obtained the significant legal reform he set out to achieve. Several articles were published about the case across the country. LaFrance received many letters from people asking for legal help and LaFrance provided them with the number to their local legal aid services. Unfortunately, within the legal professional realm, members of the Connecticut Bar Association who did not value access to justice for indigents through fee waivers ostracized LaFrance. Effects of Boddie: Parties and Attorney, Cont. New Haven Legal Assistance Association New Haven learned that attorneys with expertise in a particular area of law can apply their knowledge to subsequent areas to create real change. During the 1960s and 1970s, New Haven had several attorneys engaged in disassembling the law, taking the law in one area to expand the law in other areas. Similar to LaFrance’s successful efforts in expanding the criminal fee waiver reasoning to civil divorce cases, legal services attorneys of that era did not accept the law as it stood, but rather seized opportunities to reform the law and create a more just system for indigent clients. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society Divorce Litigation: Successes Indigent plaintiffs no longer have to pay court fees in divorce cases. Courts must arrange service of process or publication of appropriate notice of divorce claims to defendants. If not, the plaintiff may mail notice to the defendant’s last address or post notice in the appropriate place. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Divorce Litigation: Limitations However, even though pro se divorce proves practically infeasible in practice, no relief for hiring counsel exists for indigent plaintiffs. Few clerks’ offices can provide appropriate forms to divorce plaintiffs and clerks offices cannot advise plaintiffs in filling out the forms or serving notice to defendants. Although many divorce plaintiffs may need a psychiatrist or social worker to testify, no economic relief exists to compensate experts or investigators. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Civil Litigation Generally The Boddie decision lends strong support to the prospect of requiring state provision of transcripts in civil cases. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Connecticut Civil Litigation With 28 USCS § 1915 providing for federal court proceeding in forma pauperis and the Boddie decision, the Connecticut legislature followed suit, passing an in forma pauperis statute providing fee waivers for all state civil cases. Overall, indigent clients in Connecticut have benefited tremendously from fee waivers in civil cases. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Civil Litigation Nationwide Boddie set the standard for fee waivers in non-criminal cases. For example, fee waivers may apply to cases where the state requires a person to go into court for relief. Waiving fees may also extend to suits against the state and suits between private individuals, although this area was limited by Justice Harlan’s decision in Boddie. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Supreme Court Jurisprudence Boddie did not have an immediate expansive effect on subsequent Supreme Court case law. In the 1973 U.S. v. Kras decision, the Supreme Court held that the interest in obtaining a discharge in bankruptcy does not rise to the same constitutional level as the Boddie appellants’ interest in ending the fundamental marriage relationship. The Court reasoned that gaining or not gaining a discharge in bankruptcy would effect no change with respect to basic necessities. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Supreme Court Jurisprudence, cont. In Ortwein v. Schwab, the Supreme Court also rejected the basic necessities approach, holding that the interest in maintaining a given level of welfare benefits was not fundamental even though it would likely affect basic necessities. The Court upheld a filing fee against a challenge by indigents seeking judicial review of administrative decisions to approve a cut in their welfare benefits. The Court also upheld an administrative hearing as a sufficient alternative to court access. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Supreme Court Jurisprudence, cont. In Mathews v. Eldridge, the Supreme Court developed a three factor test the Court should apply in analyzing fee waiver requests in disputes between private parties: (1) consider the nature of the private interest involved; (2) weigh the risk of erroneous decisions against the value of additional procedural safeguards to prevent those errors; (3) consider the state’s interest in the request for a waiver. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. State Courts’ Jurisprudence While Boddie has not expanded civil fee waivers beyond divorce cases in the Supreme Court, many lower state courts have held that the State cannot deny indigent plaintiffs seeking divorce access to the courts for inability to pay filing fees and other costs. Therefore, Boddie has greatly impacted access to the courts for indigent divorce plaintiffs nationwide. Effects of Boddie: Law and Society, cont. Law Reform Generally Boddie serves as an example of law reform through litigation with wide success nationwide. Nevertheless, law reform through litigation has waned in the current legal era due to: Lack of funding for legal services that has muzzled many of the attorneys practicing public interest law. Law reform via legislation that has dominated as legislators have become more favorable to legislative law reform that often provides a quicker alternative to litigation. Conclusion In the realm of public interest law, Boddie proves a pivotal case in which an attorney expanded the criminal fee waiver policy to the civil realm via a carefully constructed and executed class action suit that secured greater justice for indigent plaintiffs nationwide. Demonstrates the value of creatively applying the law and policy from one legal area to other legal areas in an effort to create a more just judicial system. While law reform via litigation has subsided since the tumultuous 1960s and 1970s, litigation continues to play an important role in promoting justice and equality in American society.