Normative Theories of Ethics

advertisement

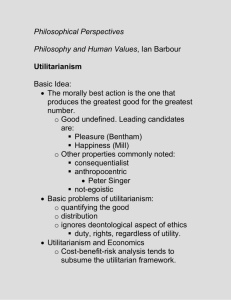

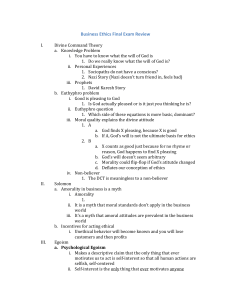

Normative Theories of Ethics • Any theory which seeks to explain or predict what would happen under theoretical constraints; what ought to be, rather than what is, or will be. • In ethics, normative theories propose some principle or principles for distinguishing right action from wrong actions. These theories can, for convenience, be divided into consequentialist and non-consequentialist approaches. CONSEQUENTIALISM • Consequentialism, as its name suggests, is the view that normative properties depend only on consequences. This general approach can be applied at different levels to different normative properties of different kinds of things, but the most prominent example is consequentialism about the moral rightness of acts, which holds that whether an act is morally right depends only on the consequences of that act or of something related to that act, such as the motive behind the act or a general rule requiring acts of the same kind. NON CONSEQUENTIALISM • A normative stance that views what should be done as determined by fundamental principles that do not derive solely or even primarily from consequences. An act or rule is right insofar as it satisfies the demands of some over-riding (non-consequentialist) principle of moral duty. Deontologists sometimes stress that the value of actions lies more in motives than in consequences. 2 Important Consequentialist Theories EGOISM UTILITARIANISM Egoism • Egoism can be a descriptive or a normative position. Psychological egoism, the most famous descriptive position, claims that each person has but one ultimate aim: her own welfare. Normative forms of egoism make claims about what one ought to do, rather than describe what one does do. Ethical egoism claims that it is necessary and sufficient for an action to be morally right that it maximize one's self-interest. Rational egoism claims that it is necessary and sufficient for an action to be rational that it maximize one's self-interest. Egoism • Personal egoists claim they should pursue their own best long-term interests, but they do not say what others should do. • Impersonal egoists claim that everyone should follow his or her best long-term interests. • Some years ago, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company announced that it was discontinuing its controversial “500” steel-belted radial, which accordingly had been associated with 15 deaths and 31 injuries. This was interpreted by newspapers as an immediate removal of the tires from the market, whereas Firestone intended a “rolling phaseout”. • It was later found out that Firestone had in fact continued making the steel-belted “500” radial, despite earlier media reports to the contrary. Immediately thereafter, newspapers reported a Firestone spokesperson as denying that Firestone had misled the public. Asked why Firestone had not corrected the media misinterpretation of the company’s intent... • The spokesperson said that Firestone’s policy was to ask for corrections only when it was beneficial to the company to do so – in other words, when it was in the company’s selfinterest. Misconceptions about Egoism • Egoists only do what they like – Not so. Undergoing unpleasant, even painful experience meshes with egoism, provided such temporary sacrifice is necessary for the advancement of one’s long-term interest. • All egoists endorse hedonism (the view that only pleasure is of intrinsic value, the only good in life worth pursuing) – although some egoists are hedonistic, others have a broader view of what constitutes self-interest. Misconceptions about Egoism • Egoists cannot act honestly, be gracious and helpful to others, or otherwise promote others’ interests. – Egoism, however, requires us to do whatever will best further our own interests, and doing this sometimes requires us to advance the interests of others. Problems with Egoism • Psychological egoism is not a sound theory • Ethical egoism is not really a moral theory at all • Ethical egoism ignores blatant wrongs Utilitarianism • one of the most powerful and persuasive approaches to normative ethics in the history of philosophy. • This theory defines morality in terms of the maximization of net expectable utility for all parties affected by a decision or action. • Moral doctrine that we should always act to produce the greatest possible balance of good over bad for everyone affected by our action. Six Points about Utilitarianism • When a utilitarian advocates “the greatest happiness for the greatest number,” we must consider unhappiness or pain as well as happiness. • Actions affect people to different degrees • Because utilitarians evaluate actions according to their consequences, and actions produce different results in different circumstances, almost anything might, in principle, be morally right in some particular circumstance. Six Points about Utilitarianism (cont’n) • Utilitarians wish to maximize happiness not simply immediately but in the long run as well. • Utilitarians acknowledge that we often do not know with certainty what the future consequences of our actions will be. • When choosing among possible actions, utilitarianism does not require us to disregard our own pleasure. Critical Inquiries of Utilitarianism • Is utilitarianism really workable? • Are some actions wrong, even if they produce good? • Is utilitarianism unjust? The Interplay Between Self-Interest and Utility • Both self-interest and utility play important roles in organizational decisions, and the views of many businesspeople blend these 2 theories. To the extent that each business pursues its own interests and each businessperson tries to maximize personal success, business practice can be called egoistic. But business practice is also utilitarian in that pursuing self-interest is thought to maximize the total good, and playing by the established rules of the competitive game is seen as advancing the good of society as a whole. Kant’s Ethics • German philosopher Immanuel Kant sought moral principles that do not rest on contingencies and that define actions as inherently right or wrong apart from any particular circumstances. He believed that moral rules can, in principle, be known as a result of reason alone and are not based on observation. Kant’s Ethics (cont’n) • “The basis of obligation must not be sought in human nature, nor in the circumstance of the world.” – Kant – Moral reasoning is not based on factual knowledge and that reason by itself can reveal the basic principle of morality. Kant’s Ethics (cont’n) • Immanuel Kant (1724– 1804) is the central figure in modern philosophy. • Philosopher whose comprehensive and systematic work in the theory of knowledge, ethics, and aesthetics greatly influenced all subsequent philosophy, especially the various schools of Kantianism and Idealism. Good Will • According to Kant, nothing is good in itself except a good will. This does not mean that intelligence, courage, self-control, health, happiness, and other things are not good and desirable. But Kant believed that their goodness depends on the will that makes use of them. • By will Kant meant the uniquely human capacity to act from principle. The Categorical Imperative • Kant believed that reason alone can yield a moral law. We need not rely on empirical evidence relating to consequences and to similar situations. • Kant’s categorical imperative says that we should act in such a way that we can will the maxim of our action to become a universal law. Kant in an Organizational Context • The categorical imperative gives us firm rules to follow in moral decision making, rules that do not depend on circumstances or results and that do not permit individual exceptions. • One of the principal objections to egoism and utilitarianism is that they permit us to treat humans as means to ends. Kant’s principles clearly forbid this. Kant in an Organizational Context (Cont’n) • Kant stresses the importance of motivation and of acting on principle. According to Kant, it is not enough just to do the right thing; an action has moral worth only if it is done from a sense of duty – that is, from a desire to do the right thing for its own sake. Critical Inquiries of Kant’s Ethics • What has moral worth? • Is the categorical imperative an adequate test of right? • What does it mean to treat people as means? Prima Facie Principles • Philosophers like W.D. Ross believe that most, or even all, of our moral obligations are prima facie ones. A prima facie obligation is simply an obligation that can be over-ridden by a more important obligation. • Ross thought that the various prima facie obligations could be divided into seven basic types. Prima Facie Obligations • • • • • • • Duties of Fidelity Duties of Reparation Duties of Gratitude Duties of Justice Duties of Beneficence Duties of Self-Improvement Duties Not to Injure Others Assisting Others • Most nonutilitarian philosophers believe that we have some obligation to promote the general welfare, but they typically view this obligation as less stringent than, for example, the obligation not to injure people. They see us as having a much stronger obligation to refrain from violating people’s rights than to promote their happiness or well-being. Assisting Others (cont’n) • Many moral philosophers draw a related distinction between actions that we are morally required to take and charitable or supererogatory acts – that is, actions that would be good to take but not immoral not to take. Moral Rights • A right is an entitlement to act or have others act in a certain way. The connection between rights and duties is that, generally speaking, if you have a right to do something, then someone else has a correlative duty to act in a certain way. • Moral rights are noneconomic rights that are considered to be the inalienable rights of the creators of works. Nonconsequentialism in an Organizational Context • NC stresses that moral decision making involves the weighing of different moral factors and considerations • NC acknowledges that the organization has its own legitimate goals to pursue. • NC stresses the importance of moral rights Critical Inquiries of Nonconsequentialism • How well justified are these nonconsequentialist principles and moral rights? • Can nonconsequentialists satisfactorily handle conflicting rights and principles? Moral Decision Making: Toward a Synthesis • Theoretical controversies permeate the subject of ethics, and philosophers have proposed rival ways of understanding right and wrong. These philosophical differences of perspective, emphasis, and theory are significant and can have profound practical consequences. Moral Decision Making: Toward a Synthesis • In any moral discussion, make sure participants agree about the relevant facts. • Once there is general agreement on factual matters, try to spell out the moral principles to which different people are, at least implicitly, appealing.