Review of chapters 1-4

advertisement

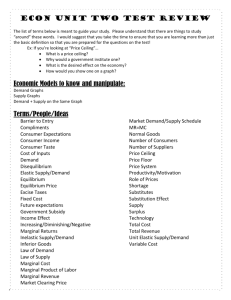

MBA 525 Microeconomics FRANK & BERNANKE CHAPTERS 1-4: THE HIGHLIGHTS Lecture 1 2 Basic concepts in economics Micro Economics vs. macro economics Opportunity cost, scarcity, “no free lunch” Opportunity cost examples “Reservation prices” (WTP The Cost-Benefit Principle and “rational behavior” Marginal analysis and quantity decisions Economic surplus (consumer surplus and producer surplus) Decision Pitfalls Lecture 2 3 The principle of comparative advantage Generalizing vs. specializing at the individual level “Low hanging fruit” The principle of comparative advantage Examples illustrating gains from trade If trade is good, why do we see opposition to trade? Lecture 3 4 Supply and Demand (price determination) Definition of a “market” “Demand” (MB, WTP), Demand schedule, Demand curve “Supply” (MC, WTA), Supply schedule, supply curve Market equilibrium (equilibrium principle and efficiency principle) Shortages and surpluses Changes (shifts) in supply and demand Price controls Lecture 4 5 Elasticity measures The price elasticity of demand Elastic vs. Inelastic demand Determinants of demand elasticity Changes in price elasticity of demand along the length of a demand curve Changes in revenue from price changes depend on the price elasticity of demand The income elasticity of demand The cross-price elasticity of demand The price elasticity of supply Overall themes 6 “Economic Naturalism” Using insights from economics to make sense of observations from everyday life E.G. Look for differences in costs and benefits Recognizing and appreciating resource scarcity and opportunity costs Understanding the way markets work 7 Lecture 1 key concepts Opportunity Cost 8 Opportunity Cost: The value of the next-best alternative that must be forgone in order to undertake an activity Decisions depend upon opportunity costs It is not the combined value of all other forgone activities, just the next best one Cost-Benefit Principle 9 Take an action if, and only if, the extra benefits from taking the action are at least as great as the extra costs Measuring the costs and benefits is often difficult One may have to use assumptions and/or approximations Helps us answer “yes/no” questions Economists assume that people make decisions this way. i.e. we assume that people are “rational”. “Rational” here means only pursuing actions where the benefits are at least as great as the costs. Reservation Prices 10 For a consumer, reservation price is the highest price one would be willing (and able) to pay for a good. This “maximum willingness-to-pay (WTP)” should be the same as the benefit (value) received from the good. For a producer, reservation price is the lowest price one would be willing (and able) to accept for a good or service. This “minimum willingness-to-accept (WTA)” should be the same as the cost (expense) incurred in producing the good. Economic Surplus 11 The benefit of taking an action minus its cost Rational decision makers take all actions that yield a positive economic surplus Should you buy or sell an item if surplus = 0? Consumer surplus = reservation price – actual price Producer surplus = actual price – reservation price Marginal Analysis 12 Comparing incremental or additional costs and benefits to help make quantity decisions. Marginal Benefit The increase in total benefit that results from carrying out one additional unit of the activity Marginal Cost The increase in total cost that results from carrying out one additional unit of the activity Can be considered more powerful than traditional CBA, because marginal analysis leads us to the “best” answer (maximum surplus), while CBA only allows for “good” answers (non-negative surplus). Marginal Analysis 13 Example: How Q MC MB $1.50 $4.00 $1.50 $3.00 3 $1.50 $2.00 4 $1.50 $1.00 many slices of pizza to eat? 1 Assume: P = $1.50 per slice 2 Note: P = cost of an additional unit = marginal cost Finding the optimal quantity 14 If the marginal benefit is greater than marginal cost Increase output (consume or produce more) If the marginal benefit is less than the marginal cost Decrease output (consumer or produce less) Optimal output is where marginal benefit equals marginal cost MB = MC The principle of diminishing marginal benefit 15 The additional satisfaction received from units of a good tends to diminish as more units are consumed. Marginal benefit curves will be downward-sloping Assumes all units are of the same quality Addictive goods may be an exception Decision Pitfalls 16 It is a mistake to use proportions to make decisions (use dollars instead). It is a mistake to ignore opportunity costs (opp costs are real economic costs that should influence our decisions). It is a mistake to use average costs and benefits to make quantity decisions (use marginal costs and benefits). It is a mistake to consider sunk costs (sunk costs are unrecoverable and they do not affect opportunity costs or marginal costs). 17 Lecture 2 key concepts The Principle of Comparative Advantage 18 If nations (or individuals) specialize in producing goods for which they have low opportunity cost and trade for goods for which they have high opportunity cost, then they can consume more via trade. Trade leads to higher standards of living. “Comparative advantage” means being able to do something at lower opportunity cost than someone else. Sources of Comparative Advantage? Principle of Increasing Opportunity Cost 19 AKA “The Low Hanging-Fruit Principle” In expanding the production of any good, first employ those resources with the lowest opportunity cost, and only afterward turn to resources with higher opportunity costs Why trade barriers & opposition to trade? 20 International trade does increase the total value of all goods and services, but certain industries may be harmed. Putting all your eggs in one basket may be unwise if trading partners have unstable economies or politics Putting all your eggs in one basket may be unwise if the future market for that commodity or product is uncertain Example of Comparative Advantage and Mutual Gains from Trade 21 Assume that Lara and Leah can spend the day either washing cars or mowing lawns. The table below shows how much of each task they could accomplish in one day if they spent the whole day doing just that task. For example, Lara could wash 20 cars or mow 5 lawns in one day. ______________________________________________ Lara Leah ______________________________________________ Cars washed 20 15 Lawns mowed 5 3 ______________________________________________ Question: Use the principle of comparative advantage to illustrate how specialization can make them more productive than they can be alone. 22 Lecture 3 key concepts An Introduction to Supply and Demand 23 What is a market? Where do prices come from? What happens if prices are set “too high”? What happens if prices are set “too low”? Do markets really achieve equilibrium? Demand 24 Shows the total quantity of a good or service that buyers wish to buy at each price On a graph = demand curve In a schedule = demand schedule Inverse relationship between P and QD As price rises, consumers want fewer items People switch to substitutes People cannot afford as much At higher quantities, consumers are willing to pay less (application of the principle of diminishing marginal utility/benefit) Daily Demand Curve for Hamburgers 25 Supply 26 Shows the quantity of a good or service that sellers wish to sell at each price On a graph = supply curve In a schedule = supply schedule Positive relationship between P and QS As price rises, a higher quantity can be sold because more opportunity costs can be covered Application of the “low-hanging fruit principle” Reflects the rising marginal costs of producing additional units Daily Supply Curve of Hamburgers 27 Market Equilibrium 28 When all buyers and sellers are satisfied with their respective quantities at the market price There is a stable, balanced, unchanging situation The supply and demand curves intersect This results in the equilibrium price This results in the equilibrium quantity The price the good sells for The quantity that will be sold Do markets really exist in equilibrium? The Equilibrium Price and Quantity of Hamburgers 29 Disequilibrium 30 Excess supply “Market Surplus” Price is higher than equilibrium price Sellers are dissatisfied Excess demand “Market Shortage” Price is lower than equilibrium price Buyers are dissatisfied Free markets have an automatic tendency to eliminate excess supply and excess demand A market surplus serves as a signal to sellers that price is too high and therefore leads producers to decrease the price A market shortage serves as a signal to sellers that price is too low and therefore leads producers to increase the price Markets and Efficiency 31 Efficiency Principle Efficiency is an important social goal Everyone can have a larger slice of a larger pie Equilibrium Principle A market in equilibrium leaves no unexploited opportunities for individuals No “cash on the table” remains All opportunities for profit have been exploited Efficiency occurs when the market-demand curve captures all the marginal benefits of the good the market-supply curve captures all the marginal costs of the good Shifting supply and demand 32 Several factors cause changes in demand or supply If there is a “change in demand”, we shift of the entire demand curve If there is a change in supply”, we shift of the entire supply curve Change in supply or demand cause equilibrium price to change. Price changes are the RESULT of shifts, not the CAUSE of shifts Shifts in Demand 33 Change in price of complement goods Change in price of substitute goods Change in consumer Income 1. 2. 3. normal v. inferior goods Change in consumer preferences Change in consumer expectations about price Change in consumer expectations about income 4. 5. 6. normal v. inferior goods Demand curve shifts rightward higher equilibrium price and higher equilibrium quantity Demand curve shifts leftward lower equilibrium price and lower equilibrium quantity Shifts in Supply 34 Change in input or factor prices 2. Change in current production technology 3. Change in prices of other goods that can be produced with the same inputs 4. Change in the number of sellers in the market 1. Favorable changes to the producer shift supply curve rightward lower equilibrium price and higher equilibrium quantity Unfavorable changes to the producer shift supply leftward higher equilibrium price and lower equilibrium quantity Example: An Increase in Demand 35 Sequence of events: 1. Conditions change such that consumers want more units at any price. Egs: lower price of complement good, higher price of a substitute, higher income, … 2. Higher Qd at all prices means rightward shift in the demand curve 3. Demand shifts right (along supply) resulting in higher P* and Q* The Effect on the Market for Tennis Balls of a Decline in Court Rental Fees 36 Example: An Increase in Supply 37 Sequence of events: 1. Conditions become more favorable to firms. Eg: lower cost of inputs 2. Firms now can earn higher per-unit profits at any price, so they wish to sell more units at all prices. 3. Firms increase Qs for all Prices = shift right in the supply curve (along demand). 4. Shift results in lower P* and higher Q* The Effect on the Market for New Houses of a Decline in Carpenters’ Wage Rates 38 Simultaneous Shifts 39 In reality, several factors may be changing at the same time. Example: suppose that consumer income is falling while technology used in production is advancing. Demand decreases (shifts left) and supply increases (shifts right) Demand shift implies a lower price & lower quantity Supply shift implies a lower price, higher quantity We can predict that price will fall But, what happens to quantity? We must know the magnitude of the shifts Legislation and Markets 40 Legislators protect producers and consumers by using price controls Price ceilings Price floors Price controls 41 price ceilings – intended to help consumers A maximum allowable price specified by law because the true equilibrium price was deemed “too high” Price ceiling price < P* so now consumers want too much e.g. rent controls, limits on the price of gasoline Result in permanent shortages price floors – intended to help producers A minimum allowable price specified by law For example, agricultural price supports, minimum wages Price floor price is > P* so now sellers want to sell more Result in surpluses 42 Lecture 4 key concepts Price Elasticity of Demand 43 In order to predict what will happen to sales and expenditures (revenue) firms must know how much quantity will change when the price changes. The price elasticity of demand is the percentage change in the quantity demanded that results from a one-percent change in its price % Q P %P D D Price Elasticity 44 Demand is said to be “elastic” if quantity demanded changes by a lot when price changes even a little price elasticity is greater than one Demand is said to be “inelastic” if quantity changes by a little even if price changes a lot price elasticity is less than one Demand is said to be “unit elastic” if quantity changes by the same amount as the price change price elasticity equals one Price Elasticity and Expenditures 45 If demand is elastic: Quantity demanded is highly responsive to price changes Percentage change in quantity dominates An increase in price will reduce total expenditure A decrease in price will increase total expenditure If demand is inelastic: Quantity demanded is not very responsive to price changes Percentage change in price dominates An increase in price will increase total expenditure A decrease in price will decrease total expenditure Determinants of Elasticity 46 Substitution possibilities Price elasticity of demand will be relatively high if it is easy to substitute between products – Why? Budget share The larger the share of the budget the good uses tends to have higher price elasticities of demand – Why? Time Because substitution takes time, price elasticity will be higher in the long run than in the short run Examples? 47 What are some goods that will have very elastic demand? Can demand be perfectly elastic? What does an elastic demand curve look like? What are some goods that will have very inelastic demand? Can demand be perfectly inelastic? What does an inelastic demand curve look like? Other Elasticities of Demand 48 Income Elasticity of Demand The amount by which the quantity demanded changes in response to a one-percent change in income Positive for normal goods Negative for inferior goods Cross Price Elasticity of Demand The amount by which the quantity demanded of one good changes in response to a one-percent change in the price of another good Positive for substitutes Negative for complements Price Elasticity of Supply The percentage change in the quantity supplied that will occur in response to a onepercent change in its price % Q %P S S P Q Q P P P Q 1 slope 49 Elasticity of Supply 50 What determines whether the supply of a particular good will be elastic or inelastic? Availability of resources used to produce the good – how quickly and easily can producers respond to a price change? Eg of good with inelastic supply? Eg of good with elastic supply? Perfect Elasticity 51 Perfectly Inelastic Elasticity of supply is zero Whether the price is high or low, the same amount is available Perfectly Elastic Elasticity of supply is infinite When additional units can be produced using the same combination of inputs purchased at the same prices Naturalist Questions 52 Why do you pay $6 for a beer in the airport when you can buy the same beer for less than $1 outside the airport? Why do you get a discounted airfare when you stay over a Saturday night? Why are there so many personalized license plates in Virginia vs. NC?