zaslow comments on aftermath

advertisement

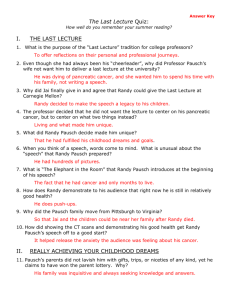

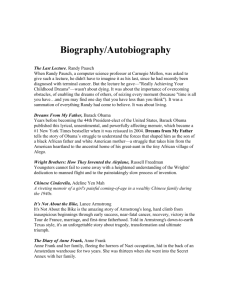

Wall Street Journal Zaslow The Professor's Manifesto: What It Meant to Readers September 27, 2007; Page D2 As a boy, Randy Pausch painted an elevator door, a submarine and mathematical formulas on his bedroom walls. His parents let him do it, encouraging his creativity. Last week, Dr. Pausch, a computer-science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, told this story in a lecture to 400 students and colleagues. "If your kids want to paint their bedrooms, as a favor to me, let 'em do it," he said. "Don't worry about resale values." As I wrote last week1, his talk was a riveting and rollicking journey through the lessons of his life. It was also his last lecture, since he has pancreatic cancer and expects to live for just a few months. After he spoke, his only plans were to quietly spend whatever time he has left with his wife and three young children. He never imagined the whirlwind that would envelop him. As video clips of his speech spread across the Internet, thousands of people contacted him to say he had made a profound impact on their lives. Many were moved to tears by his words -- and moved to action. Parents everywhere vowed to let their kids do what they'd like on their bedroom walls. "I am going to go right home and let my daughter paint her wall the bright pink she has been desiring instead of the "resalable" vanilla I wanted," Carol Castle of Spring Creek, Nev., wrote to me to forward to Dr. Pausch. People wanted Dr. Pausch to know that his talk had inspired them to quit pitying themselves, or to move on from divorces, or to pay more attention to their families. One woman wrote that his words had given her the strength to leave an abusive relationship. And terminally ill people wrote that they would try to live their lives as the 46-year-old Dr. Pausch is living his. "I'm dying and I'm having fun," he said in the lecture. "And I'm going to keep having fun every day, because there's no other way to play it." For Don Frankenfeld of Rapid City, S.D., watching the full lecture was "the best hour I have spent in years." Many echoed that sentiment. ABC News, which featured Dr. Pausch on "Good Morning America," named him its "Person of the Week." Other media descended on him. And hundreds of bloggers world-wide wrote essays celebrating him as their new hero. Their headlines were effusive: "Best Lecture Ever," "The Most Important Thing I've Ever Seen," "Randy Pausch, Worth Every Second." In his lecture, Dr. Pausch had said, "Brick walls are there for a reason. They let us prove how badly we want things." Scores of Web sites now feature those words. Some include photos of brick walls for emphasis. Meanwhile, rabbis and ministers shared his brick-wall metaphor in sermons this past weekend. Some compared the lecture to Lou Gehrig's "Luckiest Man Alive" speech. Celina Levin, 15, of Marlton, N.J., told Dr. Pausch that her AP English class had been analyzing the Gehrig speech, and "I have a feeling that we'll be analyzing your speech for years to come." Already, the Naperville, Ill., Central High School speech team plans to have a student deliver the Pausch speech word for word in competition. As Dr. Pausch's fans emailed links of his speech to friends, some were sheepish about it. "I am a deeply cynical person who reminds people frequently not to send me those sappy feel-good emails," wrote Mark Pfeifer, a technology project manager at a New York investment bank. "Randy Pausch's lecture moved me deeply, and I intend to forward it on." In Miami, retiree Ronald Trazenfeld emailed the lecture to friends with a note to "stop complaining about bad service and shoddy merchandise." He suggested they instead hug someone they love. Dr. Randy Pausch Near the end of his lecture, Dr. Pausch had talked about earning his Ph.D., and how his mother would kiddingly introduce him: "This is my son. He's a doctor, but not the kind who helps people." It was a laugh line, but it led dozens of people to reassure Dr. Pausch: "You ARE the kind of doctor who helps people," wrote Cheryl Davis of Oakland, Calif. Dr. Pausch feels overwhelmed and moved that what started in a lecture hall with 400 people has now been experienced by millions. Still, he has retained his sense of humor. "There's a limit to how many times you can read how great you are and what an inspiration you are," he says, "but I'm not there yet." Carnegie Mellon has a plan to honor Dr. Pausch. As a techie with the heart of a performer, he was always a link between the arts and sciences on campus. A new computer-science building is being built, and a footbridge will connect it to the nearby arts building. The bridge will be named the Randy Pausch Memorial Footbridge. "Based on your talk, we're thinking of putting a brick wall on either end," joked the university's president, Jared Cohon, announcing the honor. He went on to say: "Randy, there will be generations of students and faculty who will not know you, but they will cross that bridge and see your name and they'll ask those of us who did know you. And we will tell them." Dr. Pausch has asked Carnegie Mellon not to copyright his last lecture, and instead to leave it in the public domain. It will remain his legacy, and his footbridge, to the world. • Email: Jeffrey.Zaslow@wsj.com2.