Effects of the Pop Art Movement

advertisement

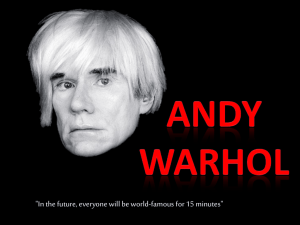

Marshall 1 Leslie Marshall English 250 Ms. Leasum 26 February 2009 Effects of the Pop Art Movement Popular Art transpired during a time of social changes. It created a widespread “Western cultural phenomenon,” that developed under capitalist, industrial surroundings in a modern society (Osterwold 6). It is a style of art that explores the contemporary aspects of daily life through forms Dadaism, a movement in the early twentieth century that exploited irony to benefit cultural analysis. First emerging in England during the 1950s, it rapidly gained attention in America during the 1960s with newfound success and awareness. Lifestyle and pop culture were becoming increasingly intertwined at the time through, connections of everyday life and the aesthetic tastes of commodities. Popular Art had the ability to reflect contemporary reality and provoke cultural change by merging the gap between fine arts and media through advertising and commercial arts, and is still doing so today. The new epoch in art resulted in the change of consumer habits and mass producers’ retail tactics. “Producers could no longer successfully exploit the customer’s needs by superimposing some sales strategy of their own design” (Osterwold 7). Artists became enthused to undertake the designing of the commonplace promotions. Creativity began to go beyond the stereotypical norms that had a tendency to dictate the patterns of style and demand. “Advertising and media provided a vast assortment of new subjects for artists to appropriate and formulate in Marshall 2 their bold, splashy style” (Johnson 30). According to Roy McMullen, these artists differed from the serious or elite artists; they represented the views of the consumer, rather than their personal views (Frith 13). Synchronization of form and content were displaced leaving reminisce of the manipulative image in the advertisement isolated. Many were able to transform trite household accessories into essential brand names that became a symbol for the new emerging mass culture. Brands like Pepsi, Coca-Cola, and Campbell’s Soup, and items like toothpaste, cigarettes, and ice-cream all became the iconography for Popular Art through ads created for the newly Andy Warhol. 100 Coca Cola Bottles. 1962. transformed middle class. Due to the post-war prosperity, an improved standard of living with disposable income and leisure time led to a boost in mass-produced media (Karizen 113). The demand for consumer goods and mass media programming was revitalized and people began to develop a new type of relationship with Kitsch. An art form that imitates the superficial side of creativity and is industrially produced (Osterwold 7). Pretentious people can find it to be tasteless art. Coca- Cola is a prime example of Kitsch. During the 1960s, it became a source of entertainment; logos appeared on glasses, tshirts, posters, etc. causing people to want to buy and collect. “This burst of exuberant consumerism inaugurated a ‘drama of possessions’ in which the acquisition of commodities became inseparable from the formation of personal identity” (Collins 5-6). Social barriers between classes began to shift due to the shared common interest in the mass commoditization, Marshall 3 making them more acceptable. “It was through all this process that the gradual convergence between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture took place” (Osterwold 7). While the designs and images were important to the era, it was the artists leading the Cultural Revolution, through Popular Art. Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, and Jasper Johns were a few of the artists who produced some of the more notable pieces during that time. These pioneers were able to integrate the superficial, mass media ideals with art’s styles and forms of expression. In 1957, Richard Hamilton wrote a letter to fellow Independent Group members, Peter and Alison Smithson and within that letter defined a term that came to acknowledge massproduced goods as a marketable, artistic phenomenon (Kaizen 113). Hamilton gave definition Richard Hamilton. Swingeing London 67. 1967-1968. to “Pop Art,” characterizing it as, “popular, transient, expendable, low cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, glamorous, big business.” Hommage a Chrysler Corp. was one of his first tabular works; clippings of car parts fragmented and decomposed into a collage that depicts the results of consumer culture (Kaizen 113). Some of his other masterpieces include: Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes Different, So Appealing, and Swingeing London 67. With these images, Hamilton reveals the emergence of horizontalization, a point when biases appear as an interpretation of the media. Andy Warhol pioneered the popular art movement through his assembly-line style, of creating largescale silkscreen paintings of popular consumer imagery (Siedell 39). His most recognizable pieces of art that had the greatest impact are 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans, Brillo Boxes, and Marshall 4 Flowers. These masterpieces were created to undermine the behavioral stereotypes associated with previous products. Earlier advertisements and media messages were repetitive, often heard by second or third hand, making it meaningless and uninspired art (Osterwold 25). He mimicked the notions of repetition and defused the usual consumer value with imagery that reflected the emotions of the time. “Today’s cult of the celebrity and love of the infamous can be directly linked to the influence of Andy Warhol, too (Johnson 29). Paintings with the faces of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Mick Jagger became iconic figures to the modern middle class, who had a growing obsession with affluence. He applied the same techniques to his famous portraits of Marilyn, Jackie, and Elvis as he did to his prior works. “Long before Warhol’s soup cans, Jasper Johns revolutionized painting with works that were right on target” (Plagens 56). In 1954, Johns Jasper Johns. Ballantine Ale Cans. 1960. painted Target with Plaster Casts, an abstract expressionism piece that represented feelings of anarchy. While it is one of his more inept designs, it was a radical addition to the rising counterculture. Flags and Ballantine Ale Cans are two pieces that represent his combining high art with the trivial imagery of daily life (Plagens 57). Each had a refined quality, but concealed it with a thick layer of paint forming a façade to generate appeal to the commonplace. Jasper Johns used his paintings to smudge the insignificant images with tachist and impressionist features; in doing so he is able to take the figurative elements and analytically revive them to compose abstract-like pieces (Osterwold 9). By the end of the ‘60s decade, the Popular Art movement had dispersed and many of the artists began reinventing their style, but the Pop Art legacy still lingers in today’s society due to Marshall 5 its connections with culture. Hallmarks of Pop Art are often reflected in fashion, architecture, museum exhibition, and media. The most recent derivative of popular art is the image-defining Hope posters that were continually reproduced for President Barack Obama’s campaign. Shephard Fairey created the mixed-media stenciled portrait of the new President, based on a photograph taken by Associated Press photographer, Mannie Garcia (Walker). Just like Warhol, Fairey drew inspiration from the shift in cultural change emphasizing political and celebrity aspects. For the 1972 presidential elections, Warhol produced an image of Richard Nixon with a caption underneath saying, “Vote George McGovern.” As said by Warhol, “the idea was you could vote either way.” Keeping an imbalanced political identity was something he was acknowledged for. The iconic illustration of President Obama is more of a direct representation of Fairey’s political ideology. “Fairey made a brief statement when he unveiled the portrait noting his ‘great conviction that Barack Obama should be the next president’” (Walker). The image spread from posters to t-shirts and to the newest end of the ingenuity spectrum, the internet. By appearing in various YouTube videos, celebrity music videos, and satirical websites the highly visible image, expanded to reach larger mass audiences; becoming the unofficial image of the campaign (Walker). The Popular Art movement emerged through forms of Dadaism, creating a style that discovered the irony of common objects in daily life through shifts in social change. Popular Art had the ability to challenge the distinction between fine arts and industrial produced commercial designs (Collins 10). The era of Popular Art centered on the idea of professionally trained artists altering iconography into the highbrow realm of museum art (Collins 6). Artists like Hamilton, Warhol, and Johns were leading the Cultural Revolution with their art, which reflected the reality of the commonplace. The ideals and behavior of thought has since passed Marshall 6 through the generations to today’s society. While styles have changed, the presence of the popular art movement can still be felt. Marshall 7 Works Cited Collins, Jim. High-Pop. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Inc., 2002. Frith, Simon and Howard Horne. Art Into Pop. New York: Methuen and Co., 1987. Johnson, Mark. “Prints by Andy Warhol.” Arts & Activities 120. 3 (1996): 29-33. Academic Search Elite. EBSCO. Iowa State University Library. 27 Feb. 2009 <http://web.ebscohost.com>. Karizen, Willam R. “Richard Hamilton’s Tabular Image.” October 94 (Fall 2000): 113. Academic Search Elite. EBSCO. Iowa State University Library. 28 Feb. 2009 <http:// web.ebscohost.com>. Osterwold, Tilmon. Pop Art. Hohenzollernring, DE: Taschen, 2003. Plagens, Peter. “Pop Art’s Poppa.” Newsweek 149. 6 (2007): 56-57. Academic Search Elite. EBSCO. Iowa State University Library. 01 Mar. 2009 <http:// web.ebscohost.com>. Siedell, Daniel. “The Other Warhol.” Books & Culture 8. 6 (Nov.-Dec. 2002): 39. Academic OneFile. Gale. Iowa State University Library. 01 Mar. 2009 <http://find.gale.group. com>. Walker, Rob. “Consumed: The Art of Politics.” NYTimes.Com 13 Apr. 2008. 02 Mar. 2009 <http:// www.nytimes.com/2008/04/13/magazine/13wwlnconsumedt.html?scp=12&sq= Marshall 8 popular%20art%20+%20barack%20obama%20poster&st=cse>. Warhol, Andy, and Pat Hackett. POPism: The Warhol Sixties. Orlando: Harcourt Inc., 1980.