Lecture 2: The International Monetary System

advertisement

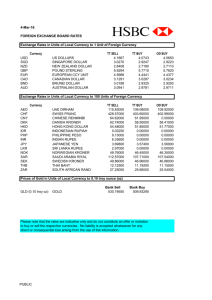

Lecture 2:The International Monetary System A Discussion of Foreign Exchange Regimes (i.e., The Arrangement by which a Country’s Exchange Rate is Determined) Cable Rate: GBP/USD (1855-1866) First Words: "Thank God, the Cable is Laid." What is the International Monetary System? It is the overall financial environment in which global businesses and global investors operate. It is represented by the following 3 sub-sectors: International Money and Capital Markets Banking markets (loans and deposits) Bond markets (offshore, or euro-bond markets) Equity markets (cross listing of stock) Foreign Exchange Markets Currency markets (and foreign exchange regimes) Derivatives Markets Forwards, futures, options… This lecture will focus on the foreign exchange market Concept of an Exchange Rate Regime The exchange rate regime refers to the arrangement by which the price of country’s currency is determined within foreign exchange markets. This arrangement is determined by individual governments (essentially how much control if any they wish to exert on the actual exchange rate). Foreign currency price is: The foreign exchange rate (referred to as the “spot rate”). Expresses the value of a county’s currency as a ratio of some other country. Since the 1940’s that other currency has been the U.S. dollar. Century before (and under the “Classical Gold Standard) it was the British pound. Foreign Exchange Rate Quotations There are two generally accepted ways of quoting a currency’s foreign exchange rate (i.e., the ratio of one currency to the U.S. dollar). American terms and European Terms quotes American terms quotes: Expresses the exchange rate as the amount of U.S. dollars per 1 unit of a foreign currency. For Example: $1.65 per 1 British pound Or $1.45 per 1 European euro Or $1.06 per 1 Australian dollar Foreign Exchange Rate Quotations European terms quote: Expresses the exchange rate as the amount of foreign currency per 1 U.S. dollar For Example: 76.67 yen per 1 U.S. dollar Or 7.80 Hong Kong dollars per 1 U.S. dollar Or 6.38 Chinese yuan per 1 U.S. dollar For reporting and trading purposes, most of the world’s major currencies are quoted on the basis of American terms (Pound and Euro); however, the majority of the world’s currencies are quoted on the basis of European terms. http://www.bloomberg.com/markets/currencies/ A Model for Illustrating Exchange Rate Regimes We can think of current exchange rate regimes as falling along a spectrum as represented by a national government’s involvement in affecting (managing) their country’s exchange rate. No Involvement by Government Very Active Involvement by Government Market forces are Determining Exchange rate Government is Determining or Managing the Exchange rate Exchange Rate Regimes Today Minimal (if any) Involvement by Government Market forces are Determining Exchange rate Floating Rate Regime Active Involvement by Government Government is Determining or Managing the Exchange rate Managed Rate (“Dirty Float”) Regime Pegged Rate Regime Classification of Exchange Rate Regimes: Floating Rate Regimes Floating Currency Regime: No (or at best occasional) government involvement (i.e., intervention) in foreign exchange markets. Market forces, i.e., demand and supply, are the primary determinate of foreign exchange rates (prices). Financial institutions (global banks, investment firms), multinational firms, speculators (hedge funds), exporters, importers, etc. Central banks may intervene occasionally to offset what they regard as “inappropriate” or “disorderly” exchange rate levels. Classification of Exchange Rate Regimes: Managed Rate Regimes Managed Currency (“Dirty Float”) Regime: High degree of intervention of government in foreign exchange market (perhaps on a daily basis). Purpose: to offset moderate market forces and produce an “desirable” exchange rate level or path. Usually done because exchange rate is seen as important to the national economy (e.g., export sector or the price of critical imports or as a means to control inflation). Currency’s exchange rate will be managed in relation to another currency (or a market basket of currencies) Preferred currencies are the US dollar and Euro. Classification of Exchange Rate Regimes: Pegged (Fixed) Rate Regimes Pegged Currency Regime Governments directly link (i.e., peg) their currency’s rate to another currency. Government sets the exchange rate with a certain band (e.g., + or – 1%) of a fixed rate or within a narrow margin, or sometimes use a crawling peg (e.g., + or – 2%) of a trend. Occurs when governments are reluctant to let market forces determine rate. Exchange rate seen as essential to country’s economic development and or trade relationships. Governments are also concerned about the potential negative impacts of a open capital market (i.e., disruptive flows of short term funds – “hot money.”) Examples of Currencies by Regime Floating Rate Currencies: Canadian dollar (1970), U.S. dollar (1973), Japanese yen (1973), British pound (1973), Australian dollar (1985), New Zealand dollar (1985), South Korean Won (1997), Thailand baht (1997), Euro (1999), Brazilian real (1999), Chile peso (1999), Argentina Peso (2002). Managed (Floating) Rate Currencies: Pegged Rate Currencies – to a fixed rate (against the U.S. dollar or market basket): Hong Kong dollar, since 1983 (7.8KGD = 1USD), Saudi Arabia riyal (3.75SAR = 1USD), Oman rial (0.385OMR = 1USD) Pegged Rate Currencies (Crawling Peg) – to a trend (against the U.S. dollar or market basket): Singapore dollar, 1981, Costa Rica colon (U.S. dollar), Malaysia ringgit (2005, Market Basket), Vietnam dong (11/08 U.S. dollar). China yuan (7/05 Market Basket), Bolivia boliviano (U.S. dollar) Note: The IMF notes that 66 out of 192 countries they classify use the U.S. dollar as a “anchor.” Data above as of 2009. Changing Exchange Rate Regimes: 1970 -2010 (IMF Classifications) % by Number of Countries % by GDP of Countries Simplified Model of Floating Exchange Rates (Market Determined Rates) The market “equilibrium” exchange rate at any point in time can be represented by the point at which the demand for and supply of a particular foreign currency produces a market clearing price, or: Supply (of a certain FX) Price Demand (for a certain FX) Quantity of FX Simplified Model: Strengthening FX Any situation that increases the demand (d to d’) for a given currency will exert upward pressure on that currency’s exchange rate (price). Any situation that decreases the supply (s to s’) of a given currency will exert upward pressure on that currency’s exchange rate (price). s s’ p p d q d’ d q s Simplified Model: Weakening FX Any situation that decreases the demand (d to d’) for a given currency will exert downward pressure on that currency’s exchange rate (price). Any situation that increases the supply (s to s’) of a given currency will exert downward pressure on that currency’s exchange rate (price). s s p s’ p d’ d q d q Factors That Affect the Equilibrium Exchange Rate: Changes in Demand Relative (short-term) interest rates. Affects the demand for financial assets (increase demand for high interest rate currencies). Relative rates of inflation. Affects the demand for real (goods) and financial assets; hence the demand for currencies Relative economic growth rates. Low inflation results in increase global demand for a country’s goods. Low inflation results in high real returns on financial assets. Affects longer term investment flows in real capital assets (FDI) and financial assets (stocks and bonds). Changes in global and regional risk. Safe Haven Effects: Foreign exchange markets seek out safe haven countries during periods of uncertainty. Safe Haven Effect: September 11, 2001 Factors That Affect the Equilibrium Exchange Rate: Government Intervention Foreign exchange intervention policy if a government feels its currency is “too weak” Government will buy their currency in foreign exchange markets Create demand and push price up. Foreign exchange intervention policy if government feels its currency is “too strong” Government will sell their currency in foreign exchange markets Increase supply to bring price down. Market Intervention by Central Banks Use the model below to explain how intervention by a central bank can respond to (1) a “weak” currency and (2) a “strong” currency (assume it wants to offset either condition): Supply (of a certain FX) Price Demand (for a certain FX) Quantity of FX Factors That Affect the Equilibrium Exchange Rate: Government Interest Rate Adjustments Some governments may also use interest rate adjustments to influence their currencies. When a currency become “too weak:” Governments might raise short term interest rates to encourage short term foreign capital inflows. Higher interest rates make investments more attractive and increase demand for the currency. When a currency becomes “too strong:” Governments might lower short term interest rates to discourage short term foreign capital inflows. Lower interest rates will make investments less attractive and reduce the demand for the currency. Factors That Affect the Equilibrium Exchange Rate: Carry Trade Strategies Carry trade strategy: A foreign exchange trading strategy in which a trader sells a currency with a relatively low interest rate and uses the funds to purchase a different currency yielding a higher interest rate. This strategy offers profit not only from the interest rate difference (overnight interest rate) but additionally from the currency pair’s fluctuation. An example of a "yen carry trade": A trader borrows Japanese yen from a Japanese bank, converts the funds into Australian dollars and buys an Australian bond for the equivalent amount. If we assume that the bond pays 4.5% and the Japanese borrowing rate is 1.0%, the trader stands to make a profit of 3.5% as long as the exchange rate between the countries does not change. In this example, the trader is short on yen and long on Australian dollars. Impact of Carry Trades on Exchange Rates Carry trades can result in a huge amount of capital flows in and out of currencies. High interest rate currency will experience increase demand. Low interest rate currency will experience increase in supply. However, when traders reverse their positions, the opposite exchange rate effects will occur. Combined this will result in a strengthening of the high interest rate currency against the low interest rate currency. When do they reverse: During periods of increasing global uncertainty about interest rates and exchange rates. For a case which combines carry trade and government intervention, please see: Case Study: New Zealand Central Bank Intervention in the Foreign Exchange Market, June 11, 2007 (posted on course web site).