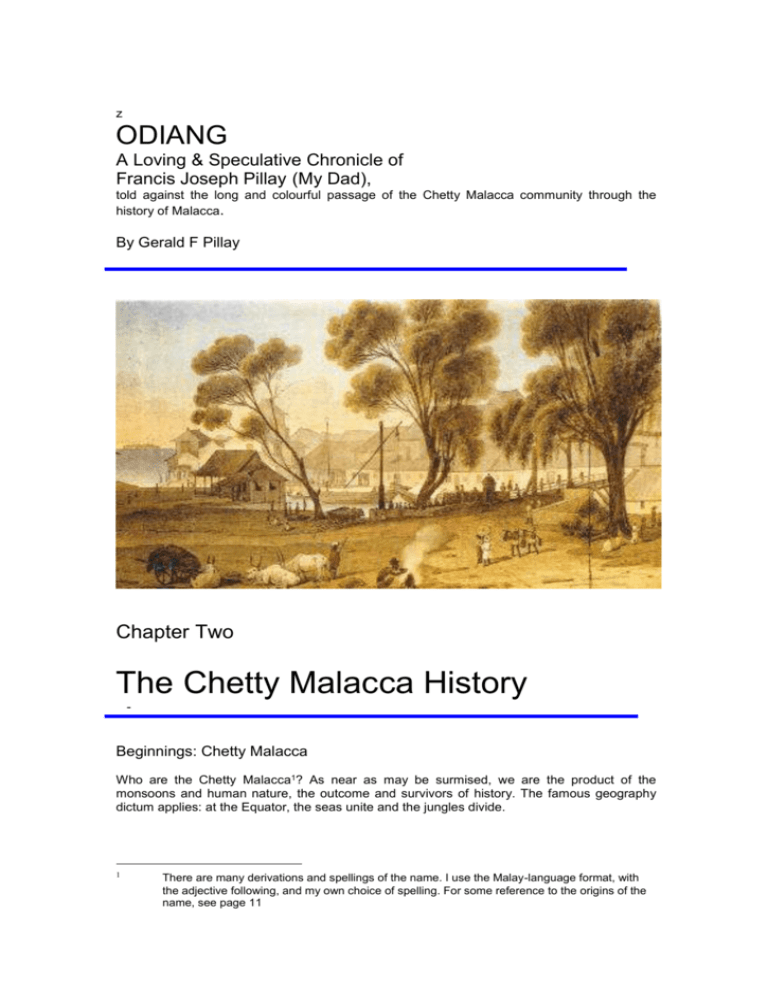

chapter-two-the-chetty-malacca-history-2

advertisement