Personality assessment

advertisement

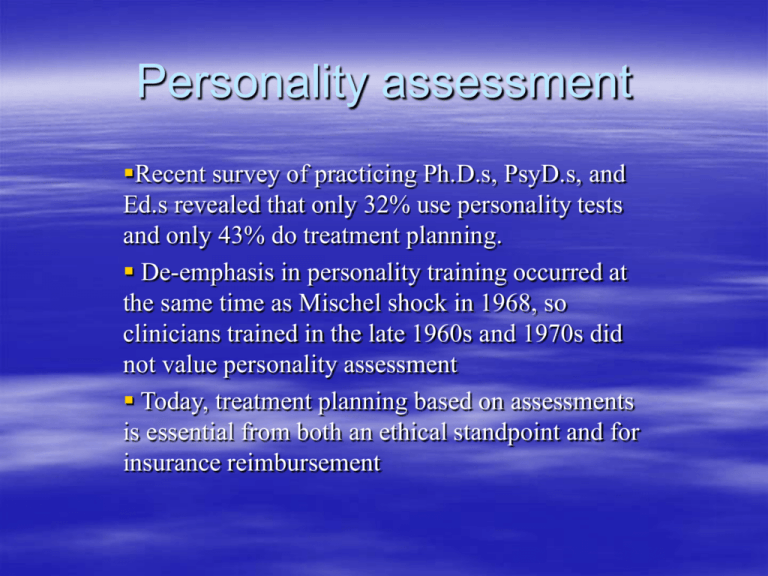

Personality assessment Recent survey of practicing Ph.D.s, PsyD.s, and Ed.s revealed that only 32% use personality tests and only 43% do treatment planning. De-emphasis in personality training occurred at the same time as Mischel shock in 1968, so clinicians trained in the late 1960s and 1970s did not value personality assessment Today, treatment planning based on assessments is essential from both an ethical standpoint and for insurance reimbursement Objective assessments? Personality assessment is subjective - for the most part it is, though subjective doesn't necessarily mean inaccurate or even less accurate. How can personality assessment be more objective – – – – assess any biases and correct for them (lie, defensiveness) find a method to avoid such biases look for convergence with reports from others assess with low face valid instruments and look for consistent patterns (though this only really addresses intentional faking) Personality assessment is used to further describe the client, just as a diagnosis does (note that you would not say that depression is causing the patient's behaviors, you merely use the term to summarize a cluster of behaviors. The diagnosis itself also does not necessarily imply a causal mechanism nor an explanation - those from different perspectives would define it differently) – e.g., if someone is depressed it could be explained biologically, cognitively, behaviorally, or even in psychodynamic terms The structure of personality Personality involves stable patterns of behavior, affect, and cognitions. So how stable is stable? (states vs. traits) Levels of analysis – 1. factors - groups of traits that show better global predictive utility (e.g., Big 5 of N, E, O, A, C; The Big 3 of N, E, P; Big 2) – 2. traits - clusters of consistent individual behaviors – 3. habits - consistent (over time) individual behaviors – 4. single acts - individual behaviors All levels are used to predict future behavior with the top being the most robust Consider this model when recommending or implementing change in clients Predicting behavior Difficult to predict specific single behaviors from global trends; (Epstein, 1983) For clinical evaluations, if the context of interest is known, then you may want to trade off the generalizability and give a specific prediction – e.g., Pt.’s test scores indicate that he is generally impulsive. This may be exacerbated when in the company of other individuals who are also impulsive and when the individual is drinking, as alcohol minimizes any inhibition processes that he might have. This substantially increases the likelihood that he will act impulsively when... Readings/Discussion I will present all of the readings (see power point slides) Read material in advance and know your MMPI You will generate 3 questions each for every reading, at least one of which will be an openended question leading to class discussion. Two scheduled “debates”: 1. Should we use a unique or standardized test battery? (Pros and Cons) 2. Should we use projective tests? (Are projectives tests or techniques) Axis I and II Personality addresses both AXIS I and AXIS II disorders. What are some AXIS I disorders that might be related to personality traits? e.g., – – – depression and NA/Neuroticism anxiety and NA/neuroticism impulse control disorders & extraversion/sensation seeking AXIS II personality disorders explicitly link up with personality assessments (video & DSM-IV) – – – – Cluster A (odd): Paranoid, Schizoid, Schizotypal Custer B (emotional): ASPD, Borderline, Histrionic, Narcissistic Cluster C (anxious): Avoidant, Dependent, Obsessive-Compulsive PD NOS – features of several Dx,but does not meet criteria for any one. Selecting a test battery (see Beutler, 1995) What is the referral question? – Single most important determinant Are there any limiting factors with regard to the client? Context of the evaluation? (work, school, hospital, etc.) Follow up assessment relevant to trait findings (e.g., patients who show impulse control problems should also be assessed for potential for acting out violently) Problem focused or broad, multipurpose battery – Nomothetic (allows for normative evaluations) or ipsative (allows for the evaluation of the individual) analysis Next Class Debate: Pros and cons of using a standardized test battery vs. a unique battery to meet the client’s assessment needs. - Use Beutler (1995) reading and any other sources. - 2 page paper and debate - For next Tues: Complete MMPI-2 and score clinical scales If using qualitative methods, consider: 1. Method appropriateness – are there quantitative methods that you could use instead? 2. Openness – make clear the theoretical orientation that undergirds the qualitative assessment 3. Theoretical sensitivity – use qualitative methods that are based on accepted theories not your own theories 4. Bracketing of expectation – you must explicitly state where your conclusions depart from accepted theories 5. Responsibility – how were the qualitative methods administered and interpreted 6. Saturation/generalizability – when assessing traits, sample from a large number and wide range of situations 7. verification of methods – cross-validate your methods using other reports, other test material to see if it agrees with your conclusions, do findings predict outcomes, etc. If using qualitative methods, consider: (cont) 8. grounding – stay close to the data when making interpretations (no big theoretical leaps) 9. coherence – do all of the interpretations fit together to make a coherent story 10. believability/usefulness – does the use of the qualitative method provide more info on the client, or just raise more questions? Does it result in a believable narrative? 11. Intelligibility – Is the report readable and jargon free? MMPI (Hathaway & McKinley, 1943) 10 clinical scales and 3 validity scales Empirical scale development with items selected based on their ability to differentiate normals, from a target group (another clinical group with similar symptoms was sometimes also employed) Clients should be 18 or older & 6th grade education Generally lower face validity (breaks with tradition of items that clearly sample the domain of interest); most relevant for clinical population MMPI development Item pool derived from psychological and psychiatric reports, textbooks, previous scales, etc. Criterion group composition – Minnesota normals – 724 relatives and visitors of patients at the U. of M. Hospitals, 265 recent high school grads, 265 administration workers, and 254 medical patients – Clinical groups – 221 patients representing the major psychiatric categories (excludes those with multiple diagnoses, or questionable diagnoses) Item analysis to identify those items differentiating the clinical and normal groups MMPI development – cont. The items that could differentiate were then cross validated with new groups of normals and patients Later developed two non-clinical scales – M/F – initially to identify male homosexuals was augmented with broader items – Si – derived from an introversion/extraversion scale and cross validated by predicting involvement in college activities in a second sample (all female college students) Validity scales were either derived rationally (L & K) or from baserates in the normal group (F) Utility of the MMPI Not considered a diagnostic inventory (as was originally intended) Ineffective at differential diagnosis (based on how it was originally developed) Numerical scale labels was intended to further minimize the connection with a specific diagnostic label Some problems with MMPI Method of determining the criterion group The PIGs were not a truly random group (relatives and friends of those in the hospital – though largely the medical patients); convenient Criterion and PIGs were largely from the midwest, in the late 1930s/early 1940s Utility of some of the scales as it matched diagnostic concerns of that era, dated and culturespecific item content, and representativeness of the norm group. MMPI vs. MMPI-2 (1989) MMPI was the most widely used personality test in all pops (though only validated for inpatient adult samples) MMPI validation and norm samples were ones of convenience with limited variability on education (M=8 years), coming from a rural background in the midwest Normative data collected in the 1930s Clinical cut-off now defined by t-score of 65 vs. 70 on the MMPI MMPI vs. MMPI-2 Advantages of updating the test – more representative norms (based on projected census data) – relevance of the items – language employed for the items (both temporally laden references like “drop the hanky”, and gender biases in item content) – addition of new scales of relevance today – Uniform T-score transformation now used so that Tscores reflect percentile ranks that are the same across all clinical scales MMPI vs. MMPI-2 Disadvantages to all updates – over 20,000 published studies no longer apply – MMPI-2 must revalidate all of the scales – inability to make comparisons with adolescent scores (MMPI-2 vs. MMPI-A) – Many of the new scales are very short and lack appropriate psychometric properties – How often should we redevelop or renorm the scale? MMPI-2 (1989): 567 items Norm group = 2,600 community based subjects – 1138 m & 1462 f, aged 18-85 (M=41, SD15.3), education 3 yrs - 20+, 61% married median incomes $25-$35,000, 3% of m and 6% of f receiving mental health treatment – 81% Caucasian, 12% A-A, 3% Hispanic, 3% Native American, 1% Asian-American Validity scales Assumption that the clinical population will not be able to answer forthright Lie – naive or unsophisticated lying (low SES and education) K – less obvious (high SES and education) defensiveness is a component of all responding F – answering questions in such a way so as to be different from 90% or more of the population (non-normative responses); See fake bad/fake good profiles F – K Index = can be used to indicate fake bad, with larger numbers making it more likely (little evidence to suggest that fake good can be detected); see p. 38 Clinical Scales 1. Hs - exaggerated concerns re: physical illness, or tendency to report symptoms 2. D - Clinical dep; unhappy & pessimistic about the future 3. Hy - conversion reactions (substitute illness for emotions) 4. Pd - History of delinquency, antisocial behavior (non-conventional re: moral standards) Clinical scales - continued 5. Mf - prototypical gender identity (military recruits, stewardesses, homosexual males students) 6. Pa - paranoid symptoms (ideas of reference, persecution, grandeur) 7. Pt - anxious, obsessive-compulsive, guilt ridden, self-doubts 8. Sc - thought disorder, perceptual abnormalities (various types of Schiz.) Clinical Scales - continued 9. Ma - exhibition of mania, elevated mood, excessive activity, distractibility, (possible manic-depression or BP II) 10. Si - college students scoring in the extreme range on introversion - extra. Costa & McCrae (1990) suggest that the MMPI-2 wont work in the normal pop. As people don’t respond “passively” to items New Validity Indexes Basic validity comes from L, F, & K VRIN (variable response inconsistency) – 47 pairs of items that should be answered similarly or the opposing direction. Client gets a point for each inconsistent response. – A completely random response set results in T scores of 96 for m and 98 for f (>80 inval.) – acquiescent responding T = 50 New Validity – cont. TRIN (true response inconsistency) – 23 pairs of items that are opposite in content – either T/T or F/F to assess acquiescent or nonacquiescent responding – larger raw scores = true responding while smaller raw scores = false responding – raw scores should be between 6 and 12 in order to consider the profile valid Fb - back infrequency items for latter part Coding the Profile List scale # codes in order of their T-score elevations (from highest to lowest) – usually only interpret 4 scale codes and order does not matter Welsh coding system involves adding symbols to numerical scale codes – e.g., L F K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 – T 57 75 43 69 88 75 94 52 81 75 79 59 65 – Welsh: 4268371095 FLK Codes (listed to the right) ** 100-109, * 90-99, “80-89, ‘70-79, +65-69, -60-64, /50-59, .:40-49, #30-39 Some coding forms use ! to denote scores of 110-119 and !! for 120 or greater Underline identical T-scores (and list in ascending order) as well as those within one point of each other e.g., 4*26”837’10+95/ F’L/K.: MMPI-2 practice case: M.S. Integrate the MMPI-2 data with the client information (vs. laundry list). Note: profile valid. – e.g., profile 3-2/2-3 should revolve around the discussion of depression and the manifestation of symptoms (physical symptoms tend to be substituted) How does this relate to M.S.? Recent loss, seeing her physician, isolation – What does the 8 (or 2-3-8) tell you? How might psychotic symptoms relate to M.S.? Confusion from malnutrition, confusion as a result of depression, her age re: dementia? All are possible M.S. - continued Include discussion of (or section on) prognosis, recommendations, and diagnosis – Axis I: 296.24, Major depression, single episode, with psychotic features – AXIS II: No diagnosis (or deferred) – AXIS III: Malnutrition, dehydration, poor hygiene & personal care – AXIS IV: Death of spouse (Severity: extreme (acute event) – AXIS V: GAF: Current, 24; highest past year, 52 MMPI-2 with other pops. MMPI was originally developed using Caucasian groups of patients Although some research has shown mean score differences between majority and minority groups, this is less relevant to the issue of whether there is differential predictive validity (few studies on this) Hall, Bansal, & Lopez, 2000, have conducted a meta-analysis of 30 years research on minority groups and the MMPI (both versions) Hall et al., 2000 - summary AA – first note that cultural identification moderates all findings (cf. acculturation) Inconsistent findings re: mean differences, with F, 8, & 9 sometimes higher by approximately 5 T-score points Many matched grouped studies of patients have found no differences, though Ns were small (meaning what?) Generally no differences in predictive validity that achieve statistical or clinical significance and any differences can be attributed to SES and age MMPI-2 has representative norms Minimal information on the supplemental scales and even less for the content scales Hall et al., 2000 – sum cont Hispanics likewise show few differences from Caucasians Possible differences for scales 3 and 0, with Hispanics scoring higher on 3 and lower on 0, but these effects were small with minimal clinical or statistical sig. Much stronger effect for acculturation in this ethnic group Few studies on Native Americans, but they show this pop. to score slightly higher on most scales Few studies for Asian Americans, and they show slight elevations for scales F, 2, & 8. Generally valid to use for these pops given appropriate acculturation and understanding of the language Other populations Given its original construction, there should be no problems using the MMPI in medical settings – Medical problems do not necessarily result in higher scores (i.e., more distress) In substance abuse settings, no profile emerged to detect substance abuse, but scale 4 was a good predictor (see also the supplemental scales) We will discuss forensic applications later in the semester (see chapter 13) MMPI-2 can be used in non-clinical settings to screen for psychopathology, but there are some concerns. – False positives are more common – Has not been validated to predict success in other settings (e.g., jobs) which is true of most personality tests (predict interest) MMPI-A (1992) Do we need a different inventory for adolescents? Why? Scales of concern? – M/F for adolescents may be less defined – Theoretically Pd is thought to be elevated, but actually it tends to be lower – Personality is less stable overall so we need different norms to better interpret scores and relevant items for this age group Valid for those aged 14-18 (for 18 y.o., the decision is based on life circumstances; e.g. at home? working?) – Important to score on both adult and adolescent norms as there can be substantial differences (T-score shifts of 15 points) 478 items (some new some from the original inventory) written & auditory forms both in English and Spanish MMPI-A Includes all of the clinical, & some new supplemental & content scales. So we use basically the same scales but different descriptors (i.e., a high score on Hs will not mean exactly the same thing for the MMPI-A; e.g., Pd equates more with acting out) Biggest change was with the F scale since it is a norm defined scale (we need new norms) Norms: 805 boys & 815 girls aged 14-18 solicited randomly from schools in 7 states. Represents the U.S. for SES and ethnicity (again minimal diffs for ethnicity) Change from MMPI which had separate norms for different adolescent age groups (now only one) F scale now has 2 parts: F1 = 1st part of test, F2 = 2nd part (F=total) MMPI-A: New scales New Supplemental scales: Alcohol/drug problem proneness (PRO) – empirically derived to assess the likelihood of alcohol or other drug problems. Items differentiate adolescents in tx from those having other psychological problems Alcohol/drug problem acknowledgement (ACK) – face valid items that reflect the admission of problems Immaturity (IMM) – reporting behaviors, attitudes, and perceptions that reflect immaturity (e.g., poor impulse control, judgment, and self-awareness). Items predict academic problems and cognitive limitations. Check for diagnoses such as oppositional-defiant, conduct disorder, and in adulthood ASPD MMPI-A Psychometrics For the most part, the psychometric properties of the MMPI-A are sound. The reliability values are lower than the MMPI-2 values, but still within acceptable limits. – Why might there be less temporal stability in the MMPI-A? General interpretative data from the MMPI-2 can be generalized to the MMPI-A, but this data should be considered in light of the client’s position in life (i.e., consider how the scores relate to school life, problems with parents, need for independence, etc.) Note: no K-correction for clinical scales even though a defensiveness score is calculated. So what are the clinical scale implications for a high K? MCMI-III (Millon, 1990) 175 item scale assessing problematic personality styles and classic psychiatric disorders (drawn from the DSM) In contrast to the MMPI, this scale was derived theoretically to match the nosology (taxonomy) of the DSM to facilitate diagnosis and intervention planning. Assumes that any assessment is theory driven (vs. MMPI which tried to be a theoretical) The theory is grounded in evolutionary principles assessing 4 spheres: existence (from serendipity to an organized structure), adaptation (survival), replication (reproductive styles that maximize diversity), and abstraction (the emergence of competencies to foster planning). Scored according to a polarity model. e.g., self vs. other orientation (reproduction), pleasure vs. pain (existential, or aim of, existence) Illustration: Schizoid is marked by deficits in both pleasure and pain as indicated by the lack of emotion and apathy MCMI-III properties A brief inventory (175 items) that takes only 30 minutes to complete 3 modifier scales that correspond to the validity scales – Disclosure = defensiveness – Desirability = favorable response set – Debasement = lying 11 clinical personality patterns: schizoid, avoidant, depressive, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial, aggressive (sadistic), compulsive, passive-aggressive, self-defeating 3 scales denoting severe personality patterns: schizotypal, borderline, paranoid 7 clinical syndromes: anxiety, somatoform, bipolar, dysthymia, alcohol dependence, drug dependence, PTSD 3 severe syndromes: thought disorder, major depression, delusional disorder MCMI-III- continued Scales interpreted based on base rates for each dx and it assumes that disorders are interconnected (consistent with comorbidity data) Initial studies had classification rates of 90%, but follow-up studies have been much lower (50% or less) Validity data has been equivocal and the reliability data is likewise lower than the MMPI-2 (these are related, and both linked to number of items) CPI (Harrison & Gough) Developed at the same time as the MMPI and served as the personality test for the normal population (MMPI for the clinical pop.). Drew from a similar item pool. 480 T/F questions (some overlap with MMPI and others are new) Emphasizes more positive/normal aspects of personality 3 validity scales: well being (normals asked to fake bad), good impression (normals asked to fake good), communality (popular/obvious responding that may reflect defensiveness and conformity) 15 general scales assessing a wide range of traits such as intellectual efficiency, capacity for status, achievement via conformity Grouped into 4 quadrants (factors): Norm favoring vs. norm doubting and externalizing vs. internalizing CPI - continued CPI was revised in 1986 with norms based on 13,000 males & females Most commonly used personality inventory overall It has been replaced by the NEO-PI as most common in the last 15 years. Psychometrically sound (reliability and validity coefficients are high and stable for different pops), but a very long instrument. Also some question as to the need for validity scales in the normal pop. – Burisch suggests this is unnecessary provided; 1) no reason to lie, 2) knowledge of the construct(s), and 3) self awareness. NEO-PI (Costa & McCrae, 1985, 1992) Based on the empirically derived 5 factor model – Assumption that 5 factors can represent all of normal personality – Evaluated this model in a variety of contexts, with samples from all over the world and in different languages – Assumes that language is the best place to start examining how to describe behavior (132 Eskimo words for “snow” indicates it is a meaningful construct) Neuroticism (emotional stability), extraversion, openness to new experience, agreeableness (quality of interactions) and conscientiousness (dutiful, organized). 5 factors have been recovered from other inventories like the MyersBriggs, 16PF, etc. NEO-PI Full version is 220 items and has 6 facets for each of the 5 factors Short form (NEO-FFI) has 60 items and provides factor scores only Norms are available for adults, college students and adolescents (though minimal differences between the latter two groups) Strong psychometric properties including very stable retest coefficients, internal reliability, and validated with other personality scales. Can be used to predict job interests (though vocational inventories such as the Strong Interest Inventory are better suited for this), but they do not predict job success (same is true for interest inventories) Often used for intuitive purposes and not empirically validated purposes (e.g., assume that a manager should be low on N and high on C vs. empirically testing this assumption with current managers) Measures of Affect Note: The EPI (Eysenck) likewise measures personality (extraversion and neuroticism) in the normal population, and these two factors are usually the first two to emerge in factor analysis. These factors correspond to the Big Two affect constructs (PA and NA) Note: most of these measures do not address validity of responding Nevertheless, research suggests that these scales tend to be fairly accurate and reflect actuarial rates for affective disorders (5-9% of adult women and 2-3% of adult men) BDI – published in 1961 and revised in ’74, ’78, and ’96. – Among the most commonly used inventories with a comprehensive manuals published in 1987, 1993, and 1996 (BDI-II) – Normed for adolescents and adults aged 13 and older. 21 items with items arranged in a Guttman approach (increasing order of severity) – Suicide potential in items 2 and 9. For dx of Depression see neurovegetative items BDI - continued Internally consistent and reliabilities range from .48 to .86 for periods ranging from several hours to four weeks – Why are retest coefficients smaller? No way to correct for faked scores Validated extensively for use in clinical settings BDI-II validated on 500 outpatients drawn from across the country and a student sample of 120 1 week retest was .93 and coefficient alphas were .92 or higher Average BDI-II scores are 3 points higher than the original BDI BDI-II time frame for each item focuses on last two weeks to match the DSM criteria BAI (Beck & Steer, 1993) 21 item symptomatic inventory Items rated on a 0-3 scale Validated for use for inpatient (N = 1,086), outpatient (N = 160) and college student samples (N=65). Shows convergent validity with other measures of anxiety and some disciminant validity with depression measures (though they are correlated – sharing 10-25% variance) Rapid self-report tool CES-D (Radloff, 1977) Developed by NIMH for use as a screening tool in the general population (also in college and geriatric pops) Optimal test for this purpose in this population 20 likert type items focusing on the last week Better than the BDI-II at differentiating among those experiencing lower levels of depression Internal consistency is high (.85 in general pop. and .90 in patient samples). Retest figures tend to be low (.48) but this is less relevant for this construct A score of 16 is clinical cutoff and it assesses depressed affect, positive affect, somatic activity, and interpersonal functioning MAACL-R (Zuckerman & Lubin, 1985) Originally published in 1965 and revised in ’85. (132 checklist type items) Normed on over 1500 adults, 400 adolescents (approx. 90% Caucasian, 10% Black) Scores for Anxiety, Depression, hostility, PA, and SS (the latter has very poor internal reliability) A rapid assessment but not as good psychometrically Can be used to evaluate states or traits and reliability figures are better (though not very high) for the latter Scales don’t corr with social desirability and do converge with MMPI ratings Behavioral Assessments Assumption: behaviors can reflect cognitions and emotions (e.g., FACS; Ekman & Friesen, 1978) Proliferation of behavioral assessments with limited validity due to the assumption that behavior can be easily defined and that it represents a meaningful (typically underlying) construct e.g., sweating, pacing How to improve behavioral assessments? – Identify the actual behavior being assessed (lip turned downward vs. sadness) – Habitual behaviors may indicate underlying condition – Acknowledge role of both traits and situations Beh assessments – cont. Also influenced by factors such as social desirability (varies depending if one is aware of the assessment) Difficult to organize and systematize behaviors (e.g., how does one smile equate with the absence of a frown re: depression?) – Very inconsistent findings regarding the organization of individual behaviors (even physical symptoms) via F.A. Why might self-report and behavioral assessments not overlap? What does this mean? Recall behavioral reactivity phenomenon – change in behavior as a function of its assessment Physiological measures “Some people want to fill the world with silly physiological measures. And what's wrong with that?” (McCartney et al., 1976) Biofeedback – long history but very mixed findings Plethysmography – changes in blood volume that may relate to emotional changes Pupillary responses – attraction and fear? Polygraph – arousal related to lying?