Chapter 33 - Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences

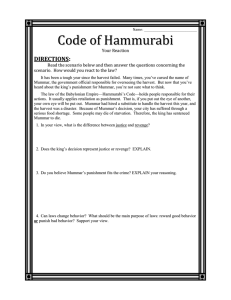

advertisement

HARVEST MANAGEMENT John W. Connelly1, James H. Gammonley2 and Thomas W. Keegan3 1Idaho Department of Fish and Game, 1345 Barton Road, Pocatello, ID 83221 2Colorado Division of Wildlife, 317 W. Prospect Road Fort Collins, CO 80526 3Idaho Department of Fish and Game, 99Highway 93 N, Salmon, ID 83467 INTRODUCTION ► Interest in managing harvests has been widespread throughout history Elements can be dated to the eighth century when Charlemagne instituted a detailed set of game laws ► ► Harvest management in North America dates to colonial times Enactment of Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Act in 1937 provided states with a stable funding source to further support harvest management programs ► For many biologists working for state and provincial wildlife agencies, harvest management is where the “rubber meets the road” ► Our purpose is to discuss the rationale and biology underlying harvest management in NA and provide examples of successful programs We also provide a synopsis of literature and attempt to identify and discuss principles RATIONALE FOR HARVEST ► In North America, states and provinces are responsible for harvest regulations pertaining to “resident” wildlife, while federal authorities set regulations for migratory game birds ►A general underpinning of a harvest management is that a biological surplus exists, which can be harvested with little impact on subsequent breeding populations Approaches to Harvest Management ► The 3 approaches to harvest management include: (1) harvesting at a low rate to ensure population increase (2) harvesting to maintain a population (3) harvesting to reduce a population Basic Components of Harvest Management ► Harvest management includes 3 basic components: (1) inventory of populations (2) identification of population and harvest goals (3) development of regulations allowing goals to be met Requirements for Successful Management ► Four basic requirements for successful, informed management of harvests 1. Develop and agree upon explicit goals and objectives 2. Implement actions designed to achieve objectives 3. Have some idea of the likely effects of alternative management actions 4. Measure the outcome of actions in relation to management objectives Principles—Past and Present ► Additive Mortality Each animal killed by hunters is an additional death that adds to natural mortality, resulting in total mortality being greater than if hunting did not occur Mackie et al. (1998) reported that hunting was additive to overwinter mortality for white-tailed and mule deer; Bergerud (1988) suggested this applied to many grouse species ► Compensatory Mortality Occurs when animals have relatively stable annual mortality, regardless of which decimating factors may be acting on the population Recent work suggests upland game hunting mortality is often not compensatory Additional Principles—Past and Present ► Diminishing Returns Indicates that, past a certain point, hunting is largely unrewarded, resulting in relatively few hunters in the field, suggesting hunting is largely self-regulating The idea of diminishing returns appears to have little value for present-day harvest management ► Doomed Surplus Number of animals produced that exceed the capacity of the habitat to support and keep secure from predation A number of wildlife species actually have high overwinter survival and this concept seems to have limited usefulness Additional Principles ► Harvestable Surplus Indicates most animals produce more young than necessary to maintain the population; this excess can be removed by hunting without affecting the population. McCullough (1979) challenged this concept by arguing that it fails to include “the dynamic and compensatory nature of population responses.” ► Inversity An inverse relationship has been proposed to exist between productivity and abundance Roseberry (1979) concluded that the system’s ability to compensate for hunting losses progressively deteriorates as harvest increases More Principles ► Opening Day Phenomenon Suggests most mortality for a given species occurs on opening day of the season because that is when most hunters are afield Appear to be few published data available documenting hunting pressure and harvest throughout the season ► Threshold of Security Population size above which some animals are not secure from predation Romesburg (1981) indicated this concept passed into the wildlife profession without being critically evaluated or tested Sources of Uncertainty ► Sources of uncertainty about the relationship between hunting regulations and game populations Partial Observability Partial Management Control Structural Uncertainty Environmental Variation Management of Upland Game Harvests ► Development of Harvest Strategies Early Years (1900–1944) ►Largely characterized by reduction in bag limits and season length for many species of upland game Changing Strategies (1945–1980) ►Harvest strategies tended to stabilize and became somewhat more liberal in the 1960s and 1970s ►There was a strong tendency to believe reproductive characteristics and effects of exploitation were the same for all species of upland game Development of Harvest Strategies for Upland Game Current Knowledge (1981–2009): A New Paradigm ►New information suggesting earlier views of harvest management were not always correct ►During 1980s and 1990s, evidence began to suggest that, under some circumstances, harvesting may have an additive effect ►Recent information suggests hunting mortality should be viewed as occurring along a continuum and not as categorical (i.e., either compensatory or additive) Inventory of Upland Game ► Inventory A general approach would base harvest on abundance of the species, but this is rarely done for upland game ►Instead, most harvest strategies seem to have been developed through trial and error Harvest Surveys of Upland Game ► Harvest Surveys Most states have reduced emphasis on population monitoring because of emphasized collection of harvest data Many estimates of harvest have wide confidence intervals, making comparisons among areas or years difficult ►Lack of population data makes it virtually impossible to assess proportion of the population taken by hunters Developing Regulations for Upland Game ► Developing Regulations Varies among wildlife agencies Initial steps include: ► Soliciting comments from agency personnel and public ► Regions or other administrative units then formulate recommendations for the chief administrator of the agency’s wildlife program ►Recommendations are discussed with the agency director ►Recommendations are passed on to the Wildlife Commission for approval Population Responses of Upland Game to Hunting ► Population Responses to Hunting Until the late 1970s, most studies suggested there were few adverse effects of exploitation on upland game Within the last 25 years, numerous studies have documented adverse effects of hunting on upland game species Kokko (2001) warned that ignoring information on species and population characteristics will “easily cause hunting to be harmful to an unnecessary extent.” Future Directions in Upland Game Management Stocking ►Seen as a legitimate and often necessary function of harvest management ►Stocking is likely reinforced among the hunting public because stocking is a common activity of fisheries management ►2 different harvest management programs involving game bird stocking Release of birds before the gun Establish or augment existing game bird populations Upland Game Shooting Preserves Shooting Preserves ►Hunting preserves offer additional hunting opportunity and a chance for individuals to train dogs prior to a general season Appear to fill a need for more hunting areas at which hunters have a better than average chance at being successful Development of Harvest Strategies for Migratory Game-birds ► Approaches have been shaped primarily by recognition these animals routinely cross local, state, provincial, and international borders ► Effective monitoring of populations and harvests, and development of regulations depends on cooperation across multiple levels of government ► Until reliable population and harvest surveys were developed, regulations in the United States were set subjectively ► As information was incorporated into the regulatory process, regional or flyway-specific differences were recognized, and regulations became more spatially complex Models for Setting Regulations for Migratory Game-birds Models were developed for use in setting regulations, incorporating information from large-scale operational monitoring programs Early models assumed hunting mortality was completely additive and density-independent Anderson and Burnham (1976) produced new analyses indicating compensatory mortality and introduced the concept of structural uncertainty Subsequent Model Analyses Subsequent analyses provided mixed evidence on effects of hunting on annual survival in ducks, but hunting mortality appears to be primarily additive for geese Recognition of alternative hypotheses about effects of hunting on population dynamics led to a greater focus on addressing partial management control and structural uncertainty After a period of stabilized regulations, federal authorities in the United States adopted risk aversive conservatism toward setting hunting regulations ►Relatively restrictive regulations would be adopted for populations at low levels Inventory of Migratory Game-birds Federal mandates to consider status of migratory game birds when setting regulations motivated development of extensive monitoring programs in North America Monitoring programs support annual regulatory process and consist of annual collection of data on abundance, production, distribution, harvest, other population parameters, and habitat Population monitoring programs for waterfowl have a longer history and are more extensive than surveys developed for most other migratory game birds Since 1955, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Canadian Wildlife Service have conducted annual aerial transect surveys, coupled with ground counts during May Winter (Jan) surveys of waterfowl have been conducted since the 1930s This survey is still the primary population index for ducks that occur outside of the May survey area, and provides population indices for many goose populations in North America During May and July aerial waterfowl surveys observers record the number of ponds containing water along transects in southern Canada and the north-central US ► The Canadian Wildlife Service monitors wetland habitat conditions on a sample of survey transects each year in southern Canada Annual Harvest Estimates for Migratory Game-birds Annual harvest estimates are obtained using surveys consisting of 2 components ►Hunter Questionnaire Survey: is used to obtain information on hunter activity and number of ducks and geese harvested each year ►Parts Collection Survey: involves mailing envelopes to a sample of hunters who are asked to mail in wings of ducks and tail feathers of geese they shoot Harvest Information Program for Migratory Game-birds In 1991, a new Harvest Information Program was initiated to provide a reliable, nationwide sampling frame of all migratory bird hunters Under HIP, each state collects the name, address, and birth date of each person hunting migratory game birds, asks each hunter a series of questions about their hunting success the previous year and provides this information to the USFWS ►The traditional sampling procedure was replaced with the HIP sampling frame beginning with the 2002–2003 hunting season Role of Banding for Migratory Gamebird Management Mark–recovery methods enable managers to obtain important information about populations. To use these methods, individually numbered leg bands are placed on migratory game birds Information helps identify distribution of harvest and harvest areas, estimate harvest rates and relative vulnerabilities to harvest of gender and age cohorts, and estimate age- and gender-specific survival rates Governmental Roles in Regulating Hunting of Migratory Game-birds ►Primary federal authority and responsibility for migratory birds was established after the signing of the Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds by representatives from the United States and Great Britain in 1916 ►Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 implemented the convention in the US This Act was later amended to incorporate similar treaties with Mexico, Japan, and Russia Under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Secretary of the Interior authorizes hunting and adops regulations for this purpose ►Regulations must be based on status and distribution of migratory game birds and updated annually ►This responsibility has been delegated to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Flyway Councils In 1947 the United States was divided into 4 administrative Flyway Councils for establishing annual hunting regulations Through these Councils, representatives from state and federal agencies in the United States, Canada, and Mexico have coordinate management activities and develop annual hunting regulations The Regulations Process Regulations process Month Monitoring January February March •Midwinter waterfowl and crane surveys •Parts Collection Survey wing bees •Hunter Questionnaire Surveys; banding analysis for duck harvest and survival rates April–May Breeding waterfowl and habitat, dove call-count, and woodcock singing-ground surveys SRC meets to recommend “early” season regulations Harvest survey results available June Harvest survey results available Flyway Councils develop recommendations July Waterfowl production surveys SRC recommend “late” season regulations August Preseason duck banding “Early hunting” seasons begin September Autumn surveys for sandhill cranes, greater white-fronted geese “Late” hunting seasons begin October U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service regulations Committee (SRC) meets to identify issues Flyway Councils develop recommendations Management of Migratory Game-bird Harvests ► Features of adaptive harvest management for mallard populations ► Set of alternative models Measure of reliability for each model Limited set of regulatory alternatives Objective function or mathematical description of the objective(s) The setting of annual hunting regulations involves a 4-step process: Each year the optimal regulatory alternative is identified Once the regulatory decision is made, model-specific predictions for subsequent breeding population size are calculated When monitoring data are available, model weights are updated New model weights used to start a new iteration of the process Harvest Management of Overabundant Species Primary goal for migratory game birds continues to be prevention of overharvests However, hunting has often been used to reduce or control the density of birds on local scales Several continental populations of geese have grown rapidly ►In 1999, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service authorized new methods of take for light geese and established a conservation order permitting take outside dates established by Migratory Bird Treaty Act Management of Big Game Harvests ► In contrast to harvest management of upland game and waterfowl, management of big game harvest is often more complex and contentious because: Ability of hunters to differentiate among gender and age classes Variety of weapons used for harvest MANAGEMENT OF BIG GAME Populations ► Management of large mammal populations is a 4-step, linear process (1) inventory (identify current or potential population status) (2) define goals and objectives (identify desired population status) (3) develop strategies to achieve objectives, (4) evaluate how well strategies met objectives Inventory of Big Game Typically involves estimating current population status Biological capacity to produce and sustain a given species ►Should be based on geographical areas containing relatively discrete populations Inventories may be designed to estimate population abundance or provide an index to population status ►Determine age and gender ratios Harvest Surveys for Big Game ► Harvest Surveys Surveys conducted by wildlife agencies estimate harvest across multiple species, seasons, weapon types, and management units ►Data collected include number of animals harvested by gender and age class, hunter effort, location, date of harvest, weapon used ► Variety of methods to estimate harvest: ►Check stations, mandatory checks, report cards, random mail or telephone surveys, toll-free telephone service, Internet- based reporting Harvest Strategies for Big Game ► Development of Harvest Strategies Harvest theory for most big game species is generally based on concepts of biological carrying capacity (K) and density-dependent population growth ►Determination of K for wild populations is very difficult; K often changes through time Practical management of big game populations is more likely to be based on social carrying capacity Developing Regulations for Big Game Wide variety of harvest regulations and season structures are applied across jurisdictions and species ► Local tradition and history often play important roles in determining harvest systems Regulations should be easily understood by hunters and enforceable ► Concept of fair chase is integral to developing regulations, but definition of fair chase varies To provide a framework for evaluation, managers should implement regulations that are consistent and stable over long enough periods to encompass normal variability ► Changing season length and timing annually will virtually eliminate the possibility of estimating effects of different season structures Evaluation is an often neglected aspect of the regulation process Population Responses of Whitetailed Deer to Hunting ►Challenge for managers is finding ways to increase harvest, particularly for females ►Principles of sustained yield management based on density dependence can be applied with more certainty than in more variable systems Population Responses of Mule Deer to Hunting ► Minimum APRs are generally effective at reducing buck mortality and increasing total buck:doe ratios, but have almost invariably failed to increase mature buck:doe ratios or absolute number of mature bucks ► Effects of altering season length are equivocal and typically confounded by concurrent change in season timing In general, reducing the number of days available to hunt has a negligible effect on total harvest ► Altering harvest management to increase buck ratios for the explicit purpose of increasing productivity is unwarranted ► Effects of female harvest depend on adult female natural mortality rates and fawn recruitment Determine appropriate harvest rates based on population-specific demographic data and population monitoring Population Responses of Elk to Hunting ►Several regulatory approaches have proven successful in increasing bull:cow ratios ►Moving centerfire-weapon seasons out of rut typically reduces bull harvest rates ►Maximum APRs (i.e., spike-only) may increase bull ratios ►A somewhat complex season system designed to attract hunters to seasons where they would be less successful may increase bull ratios Population Responses of Bear to Hunting As harvest rates increase, average age of males declines and proportion of females in harvest increases ►If females comprise ≤35% of harvest and average age of males is ≥4, population is likely stable ►Refuge areas may serve as repopulation sources for more heavily hunted areas Sustained Yield Management Maximum sustained yield (MSY) is achieved when populations are at approximately K/2 Management for MSY has received criticism and been blamed for overharvest of some species In systems characterized by large variability in weather and habitat, density-dependent population responses may be overshadowed by stochastic processes, thus reducing appropriate yield levels Principles of Sustained Yield Management ► Any exploitation of a population reduces its abundance ► Below a certain exploitation level, populations may be resilient and increase survival and/or production and growth rates to compensate for individuals removed ► ► When populations are regulated through density dependent processes, exploitation rates will tend to increase productivity and reduce natural mortality of remaining individuals Exploitation rates above maximum sustained yield will reach a point at which extinction will occur if exploitation is continued ► Age composition and number of animals remaining after exploitation are key factors in the dynamics of exploited populations ► If a population is stable, it must be reduced below that density to generate a harvestable surplus ► For each density to which a population is reduced, there is an appropriate sustained yield ► For each sustained yield, there are 2 density levels at which it can be harvested ► Maximum sustained yield may be harvested at only one density, about 1-half resource based carrying capacity SUMMARY ► As interest of nonhunters in management increases, importance of biologically defensible harvests also will increase ► Changing landscapes will alter at least some wildlife populations Approaches to harvest management for some populations will likely have to change ► Management decisions backed by sound science and rigorous data collection will alleviate some difficulties