TBI and Crime

Brain Injury & Crime:

Social emotional processing deficits in childhood and risk of offending

Huw Williams

School of Psychology

University of Exeter

&

* Emergency Department

Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital w.h.williams@exeter.ac.uk

Centre for Clinical Neuropsychological Research (CCNR)

NHS

Anti-social Personality and brain activation…

Birbaumer and colleagues (2005) –fMRI

& clips of emotive film of facial expression

(eg fear).

“psychopathic criminals” lacked activation in limbic structures less amygdala activity = the higher score for “psychopathy”

? a lack registering fear linked to lack of inhibition

seeing fear inhibits one from acting violently (see

Mobbs et al, 2008).

PFC (Pre-Frontal Cortex) & Amygdala

Raine et al. (1998) - using (PET) normal functioning in the Pre Frontal Cortex of

“predatory” murderers BUT “impulsive” had reduced activation in the PFC & enhanced activity in limbic structures. reductions in pre-frontal cortex & angular gyrus & corpus callosum in violent murderers –

? poor inter-regulation of cognition and emotion

(eg inhibitory systems of left hem not affecting right etc.)

Cautions…against primacy of biology

What might cause these differential patterns of activation is not known

Anti-social Personality Disorder (APD) often occur in the context of a range of issues - history of childhood maltreatment or trauma may be common.

“There are no concrete biological markers – genetic or physiological – that can predict [ASP] behaviour” (Mobbs et al, 2008)

AND

When there is a biological risk eg from

Birth complications

Minor physical anomalies*

Environmental Poisoning (e.g. lead)

Mal-nutrition (leading to brain mal-development)

Such issue is not usually significant unless there is a “evocative environment”

“presence of negative psychosocial factor” (Raine, 2002) (esp. maternal rejection*)

Brain Areas that typically Injured…

frontal-tempo-limbic systems are crucial for

Monitoring arousal level & control of behaviour towards “goal states”

Injury often leads to:

impulsivity, poor planning, inadequate response inhibition and inflexibility (Milders,

Fuchs & Crawford, 2003).

&

“poor anger management (reactive), irritability and impulse control are common” (Hawley et al.

2003).

personality and emotional deficits – due to de-

coupling of cognition and emotion has been described by Damasio (1994), as “acquired sociopathy”” -

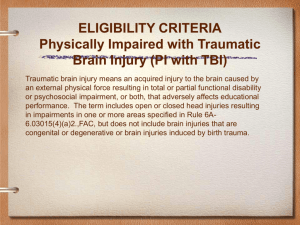

Brain Injury: Scale of problem

“TBI is an epidemic … yet it is silent … the public largely seem unaware of it… …”

Thurman, 2002

Head Injury is the leading cause of death and disability in children & working age adults

(Leurssen et al, 1988; Graham, 2001; Maas et al, 2006)

Prevalence rate of 8% (Silver et al, 2001) to 30% (McKinley et al,

2008) in population studies

Yates, Williams et al. 2006, JNNP

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

MIXED RURAL - Female

Age Group

URBAN - Female MIXED RURAL - Male URBAN - Male

Differences in socio-economic status (SES) between attendees with MHI and Orthopdedic (OI) comparison group.

SES determined by the “Index of Multiple Deprivation” and put into quintiles.

A greater proportion of those with MHI are in the 2 most deprived quintiles than in the comparison group with upper-limb orthopaedic injuries (OI).

Chi-square = 36.4, p < 0.001.

Percentages of attendees in the deprivation (IMD) quintiles compared to the local population

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

Population total MHI total OI total

3

2

5 (afluent)

4

1 (deprived)

Poverty puts children at higher risk of accidents

WHO REPORT Guardian – 10.12.08

"Over the last 20 years, there have been very dramatic decreases in child injury deaths," said Prof. Elizabeth

Towner…but "The figures mask a very deep social divide, a strong and persistent social divide," she said. "The poorer children have not shared equally in the progress of the last 20 years."

What are the rates for TBI in prison populations?

mental health & drug/alcohol problems identified

“relative to general population, [prisoners]…experience poorer physical, mental, and social health…[more] mental illness and disability, drug, alcohol…suicide, self harm…lower life expectance [etc.]…” Orme et al. BMJ editorial, 2005, 330. p 918 and see Fazel & Danesh ( 2002a (Lancet))

Studies seldom examine the serious physical illnesses OR intellectual disability prevalent in prisons

“….delivery of services to prisoners with anxiety and affective disorders, drugs and alcohol problems, brain injury , learning disability, challenging behaviour and repetitive self-harm has changed little or worsened.” Dearbhla Duffy, et al. (2003) p. 242

(our emphasis)

Report of the New South Wales Chief Health Officer

- 45% male and 39% female reported at least one head injury… www.health.nsw.gov.au/public-health/chorep/prs/prs_chronic_type.htm

TBI in Prison Populations

Barnfield & Leathem (98) NZ study:

118 respondents to questionnaire survey

86.4% reported some form of head injury (56.7%

MORE than 1).

Reported ++difficulties with memory and socialization

Rates of Mild – Severe TBI in Prisoners

Mewse, Mills, Williams & Tonks et al (in prep)

453 males held in

HMP Exeter

Pps:

196 aged between

18 and 54 years

(43% response rate) sentenced or remanded

Other

Murder/manslaughter

Robbery

Sexual offences

Drugs offences

Fraud/deception

Driving offences

Missing

Burglary

Shoplifting/theft

Violent offences

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

140

Percentage of population reporting TBI

& type of injury

“Any tbi?”

No

Yes

39.6 %

60.4% we estimate that

65% may have had a TBI.

• 10% Severe

• 5.6 % Moderate

• 49.4% Mild

Average age at 1st imprisonment:

21 – Non-TBI

16 - TBI

Number of severe tbi

Number of moderate t

Number of mild tbi

Missing No Yes

Any tbi?

8.00

7.00

6.00

5.00

4.00

3.00

2.00

1.00

19.

5

Mild TBI

Missing

Number of mild tbis

No %

0.00 = NO TBI and

Mod-severe TBI)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

1.00

19.5

2.00

16.9

3.00

6.7

4.00

2.1

5.00

3.1

6.00

.5

7.00

.5

8.00

.5

.00

TBI a risk for Crime?

- Population based study

Timonen et al (2002)

population based cohort study in Finland involving more than

12,000 subjects

TBI during childhood or adolescence associated with

fourfold increased risk of developing later mental disorder with coexisting offending in adult (aged 31) male cohort members (OR

4.1)

TBI might have been a result of high novelty seeking and low harm avoidance in people susceptible (for issues of genetics, family background, social forces etc.) to risky behaviours – coincidental to crime….BUT

TBI earlier than age 12 were found to have committed crimes significantly earlier than those who had a head injury later

Therefore - temporal congruency suggests a causal link

TBI in Prisoners: crime profiles and effects

Leon-Carrion J, Ramos FJ. (2003) (BI)

Retrospective factor analytic study of links between head injuries (in childhood and adolescence) in adult violent and non-violent prisoners.

subjects in both groups had a history of academic difficulties.

Trend for both groups to have had behavioural and academic problems at school

Head injury in addition to prior learning disability/school problems increases chances of having a violent offending profile

Violent offending (noted) to be “associated with non-treated brain injury”

? rehabilitation of head injury may be a measure of crime prevention

TBI & Crime: Coincidence or causal?

Turkstra et al. (2003)

offenders with TBI against “true peers” without TBI

20 individuals convicted of violent crime compared to 20 non convicted controls (matched for education, age and employment).

TBI NOT more common in the offender group BUT there was variance on

severity

of injury

non-offending group– typically – Milder TBI from (eg sports). offending group injuries

More assaults (with probable longer lasting changes in behaviour). had more issue related to anger control.

TBI is not necessary for crime, but that TBI may contribute to

“expression of violence” - increase the risk “threshold” in vulnerable people.

TBI a contributory factor:

Multiplicative Model

Kenny et al (2007) juvenile detention in Sydney-

242 young offenders (76% response rate)

Alcohol, substance abuse,

TBI and cultural backgrounds offences rated as:

low (common assault) moderate (robbery with weapon) serious (homicide).

85 individuals had experienced a head injury

Violent offending more common for those with KO history

TBI a contributory factor:

Multiplicative Model

odds ratios:

of 2.37 for having s serious violent crime if the young offender had had a head injury.

2.82 if the YO had been unconscious. hazardous alcohol drinking history increased risk of severe violent offending. regression models produced “multiplicative model” of how TBI is related to crime.

Childhood Brain Injury & Social impairments

Injury leads to (potentially) an array of problems:

•Attention, working memory, disinhibition etc.

See at Catroppa &

Anderson, 2004

•Dose response

•Selective

•Some recovery

Social behavioural problems:

may not be evident until adolescence

(Lishman, 1998; Teichner & Golden,

2000)

may occur in isolation from cognitive deficits (Anderson, Northam, Hendy

& Wrennall, 2001)

•lack of “moral” reasoning.

(Damasio 1996; Anderson, Bechara, Damasio,

Tranel, & Damasio, 1999; Hanks, Temkin,

Machamer & Dikmen 1999; Levin & Hanten,

Powell, 2004).

• Often there is inappropriate social behaviour

the most common and disruptive issue

(Henry, Phillips, Crawford, Theodorou &

Summers, 2006)

Anger episodes more “reactive” than “planned” in adolescence

(Dooley et al. BI, 2008)

Symptoms persist long-term post-injury.

(Anderson 2003)

The Role of Theory of Mind and Empathy

Theory of Mind (ToM):

ABI may impact on skills

to attribute mental states to others, to know they have beliefs, desires and intentions that are different from one's own for emotional understanding of others (ToM and

Empathy)

Early components achieved by 4yrs, later developments by 11yrs

these deficits may be a key issue in social situations…

Empathy:

to recognise or understand another's state of mind or emotion

& “co-experience” their outlook or emotions within oneself "putting oneself into another's shoes”

Sophisticated levels achieved during early adolescence

Both skills are fluid during childhood

→ likely to be vulnerable to the effects of an acquired brain injury (ABI)?

e.g. misperceive elements of a

situation (not reading emotion of others & perceive threat when there was none), make poor social

judgements (and behave inappropriately) and lack communication skills to negotiate out of conflict

(Turkstra et al 2003)

Understanding others through non-verbal cues

Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882)

The Expressions of Emotions in Man and Animals . London: John Murray,

1881.

“Expression of emotion evolve from behaviours that indicate what an animal is likely to do next…If these expressions benefit the animal that displays them, they will evolve in ways that enhance their communicative function…”

Tonks et al, 2007/2008: A HEURISTIC FOR SOCIO-EMOTIONAL PROCESSING

External stimuli

Functional at birth. Enables association learning.

Thalamo amygdala pathway.

Intrinsic emotional arousal/ control system.

Amygdala.

Emotion Recognition.

Eye gaze detection/reading

Hippocampus

External context information

Emotional response

Develops rapidly during the 18 months following birth, with an identifiable further significant stage of improvement at around

11 years old

Face expression analysis

Sensory/ spatial analysis system.

Vocal Analysis

Eye Configuration analysis

Develops throughout childhood and adolescence, assuming increasing executive control over emotions.

Affect perception

Executive system synthesis .

Executive functioning

Emotion regulation control

(Le Doux, 1999; Rolls, 1999; Hornack, Rolls & Wade 1996; Jackson

& Moffat, 1987; Baron-Cohen, 2000; Evans, 2003)

Tonks, Williams et al - Emotion processing post ABI

Male or Female

Mean Time

Lapse Since

Insult (yrs)

Mean Injury

Age

(yrs)

Nature/ Frequency of

Insult.

(M=Male, F=Female)

Age group

Nine to ten male

2 female

1

Total

3

2.17

5.3

Ten to eleven

Eleven to twelve

1

3

1

1

2

4

.88

5.4

9.8

5.17

M= 1 Severe TBI, 1 Stroke.

F= 1 Severe TBI

M= 1 Heamorrage (AVM).

F= 1 Meningitis

M= 1 mild TBI, 2 Tumour.

F= 1 moderate TBI

Twelve to thirteen 6.46

2 0 2 6.33

M= 2 Severe TBI.

Thirteen to fourteen 6.14

2 1 3 7.17

Fourteen to Fifteen

Fifteen Plus*

4 0 4

2.89

11.42

Table 5: Summary and injury profiles for the ABI participants in the study

1 1 2

2.33

13.79

Group Total

15 5 20

M= 1 Severe TBI, 1 mod

TBI. F= 1 Severe TBI.

M= 1 Severe TBI, 1 mod

TBI. 1 mild TBI. 1 Stroke.

M= 1 Severe TBI.

F= 1 Severe TBI

TBI=14, Meningitis=1,

Tumour=2,

Heamorrage=1, Stroke=2.

Tonks, Williams et al - Emotion processing post ABI controls

67 (age matched) children were recruited from primary and secondary schools. These were given the batteries of tests.

78

76

82

80

74

72

70

68

Group

AB I

How do ABI children compare to non-injured children?

Healthy

F(1,85)=14.227 p<.000

ANCOVA (FAS):

F(1,84)=10.992 p<.001

70

60

50

Group

AB I

How do ABI children compare to non-injured children (“Mind in the Eyes”)?

80

70

Healt hy

60

50

40 up to 1 1

PIAGR OUP

11 to 1 2

Group

AB I

12 Pl us

He al thy

Face-emotion processing problems in children with ABI

(Tonks et al, 2007/2008/2009)

Group trends:

•those with difficulties with angry faces experienced peer problems

• poor at identifying expressions reported less pro-social.

•Specific deficits

•KL - not recognise sad faces

• MN – not “getting” emotional tone. He could not understand sarcastic remarks

•OP- reads all “eyes” as hostile. increasingly violent

[also see: Milders, Fuchs and Crawford 2003 re: adults with TBI;

Skye MacDonald & colleagues re: TASIT (awareness of social inference)]

Static vs. Dynamic tasks.

dynamic cues- movement and interaction- have been shown to be dissociated from static cues

(Adolphs, Tranel &

Damasio, 2003; McDonald & Saunders, 2005).

dynamic cues are infrequently used in research and clinical assessments

(Atkinson & Adolph, 2005).

a gap between clinical assessments and reported social behavioural problems?

Communicating social emotions skills

Tonks, Williams, Frampton, Yates, Slater (in prep)

20 ABI children aged 9 to 15 yrs (M 2.5, SD 2.1) were compared to closely age matched controls (M 11.6, SD

2.2).

Parents of all participants completed the Parent SDQ as a measure of socio-emotional behaviour.

THEN, all participants watched the following Movie…

MOVIE CLIP:

Inspired by Heider and Simmel

“So they are having a game and he pushes that stick down and he is trapped. and sad. and they have gone off together. They made friends. so he is left out and is sad now” (C, aged 5)

Comparisons: ABI vs. controls:

Differences in Motion (“moved to”)

and Emotion (“sad”) words used.

ABI children and controls did not significantly differ in terms of % of Motion words used to describe the film.

Neither did they differ significantly in the % of Emotion words used.

Comparisons: ABI vs. controls:

Differences in Social communication words used.

Condition

Free description **

Guided Questions **

Combined mean score *

ABI children

M SD

2.19

3.4

.86

.5

1.6

.08

M

Controls

SD

3.13

.3

3.97

3.08

4.6

3.3

** p<.

01, * p<.

05

BUT - they did differ in terms of the number of social communication words used to describe the movie.

Peer problems (on SDQ) correlated with lack of

‘Social communication’ words ( r =-0.47, p= 0.037)

Theory of Mind & Empathy in adolesence

Sarah Wall, Huw Williams, & Ian Frampton

ToM

A Test of Social Processing (Turkstra et al., 2001)

Faux Pas test (Baron-Cohen et al., 1999)

Empathising

Socio-Emotional Questionnaire for Children

“I (he/she) notice(s) when other people are happy”

“I (he/she) prefer(s) being alone than with others”

+ Strengths and Difficulties Q & DEX-C

(Dysexecutive)

Empathy in non-injured children in early adolesence

(100+ boys and girls) (Wall et al. in press)

42

41

40

39

38

37

36

35

Girls

Boys

11 12 13 14

Age boys tended to show a decrease in positive social-emotional functioning, alongside self-reports of increased anti-social behaviour.

Those with a history of MTBI rated particularly low

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

18

17

16

15

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

Theory of Mind (complex) & Critical age of injury

Wall, Williams, Frampton (in prep)

BI TD

Boys

Girls

25 young adolescents (10 to 15yrs) with a history of ABI, 50 typicallydeveloping (TD) matched controls

Global impairments

Poorer empathic responding

Less accurate ToM

Faux pas

SEQ-Kids

Parental reports of poor emotion recognition and empathy

Self-reports of poor emotion recognition and empathy

+ executive impairments (DEX-C

+ EF measures), increased daily difficulties and impact (SDQ)

Birth to 2 2 to 6 6 to 12 +

Age at injury (years)

Average

Borderline/impaired

TBI and Crime – causal or co-incidental?

The evidence is not clear cut

there are many confounding factors within the relationships between injury and later offending

the link between crime and TBI may be an epiphenomenon whereby criminal behaviour “particularly violent crime, is likely to result from complex interaction of factors such as genetic pre-disposition, emotional stress, poverty, substance abuse and child abuse”

Turkstra, 2004 (P 40).

BUT: TBI may be an important factor in offending behaviour.

“poor prefrontal function [may be associated with] impulsive violence,

[but] this brain dysfunction may be… a predisposition only” p.54 Raine,

2002

MOREOVER: catch 22…

“The person at risk of violence needs to recognise his risk and take preventative steps…but [those with]…damage to…prefrontal cortex…may not be able to reflect on their behaviour and take responsibility…[as their] internal soul-searching [is] damaged…”

Raine (2002)

Screening…for sentencing & rehabilitation*

So we need:

better screening for head injury at pre-sentencing and on admission to prison/custodial services –

for better understanding of risk, and for rehabilitative purposes

Esp. those with executive (& socio-affective) difficulties who may have difficulty in changing behaviour patterns in response to contingencies.

…Developmental issues…

Developmental factors may be particularly important:

There may be sleeper effects – esp. relevant to socio-emote functions at transition to adolescence public safety and long term economic advantage could be gained by better, earlier, targeted interventions to

prevent injury, reduce impact of injury

Systematic neuro-rehabilitation -

Targetted at ?socio-emotional processing (esp. ToM/Empathy etc.):

eg “Mind Reading: An Interactive Guide to Emotions” (Baron-

Cohen, 2004)

Impulse control? (Stop, (breathe!!) Think, Do! (or DON’T Do))

"Brains become minds when they learn to dance with other brains”

W.J. Freeman