File - Cory Snow's Educational e

advertisement

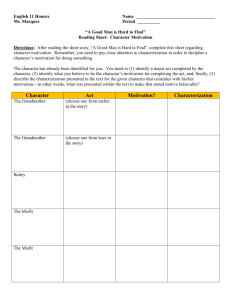

Exploring Our Common Humanity: Characterization of People and Place A Professional Piece Cory Snow English/Language Arts Teacher Skyview High School, Billings, MT Montana Writing Project Summer Institute-East 2011, Joliet, MT Think of the last novel you enjoyed (for me, The Graveyard Book, by Neil Gaiman), the last movie you recommended to an acquaintance (The Boondock Saints), the last TV show you just had to see every week (Lost). Chances are you did so because of the ability of that medium to convey to you rich, deep, believable characters and places full of emotion and real-life human connection. In some of the very best writing, the place even becomes a character! In short, you cared enough about these characters even though they weren’t a physical presence in your life. Though simply depicted in a given milieu, they were, for a time, real enough for you to make a real connection to the plight(s) they faced. We crave these kinds of connections, and we’ll take them any way we can get them. For some, the more traditional mediums of books, TV, movies, comics, and the like fill the need. These media allow people to make connections to characters and places that are depicted, just as they would connect to a physical person or place. Others look to online gaming communities or incessant texting, tweeting, poking, facebooking or whatever social networking medium du jour is popular to get their human connection fix. The development of many of these forms of entertainment (or time wasting activities as some would call them) offers a safe, consistent, one-way connection that can be severed at any time, unlike a real life, flesh-to-flesh, face-to-face human relationship. We make similar connections to place, especially the place we grew up or call home, where, again, place literally becomes a character in our life. From now on, every time I use the word “character” I am also referring to place being cast as a character. I teach upper level English courses which are, by my school district’s mandate, very heavy on literature. My students tend to dislike many of their English courses throughout high school because they have to read, analyze and criticize works that don’t resonate with them, are difficult to understand, or are just really old, outdated, and archaic. How can I as an educator bring my learners to a place where they can evaluate the work critically when most have little or no motivation to read the text in the first place? By shoving it down their throats? By making tests, quizzes and formal essays worth so many points that the students fail if they do poorly? By spoon-feeding the material to them, coddling and babying them the whole time? No. High school students—who by the way are human beings just like everybody else (though I can see why people would have doubts)—crave connections with other human beings. It’s the way we are. So through studying the usage of characterization to create dynamic, powerful accessible characters in all forms of media, past and present, I hope to convince these young people that these works they are so dreading have worth to their lives in the 21st century. Evolutionary Psychobiologist Paul MacLean researched the difference between the brains of mammals and the brains of reptiles, and found that an area of the limbic system called the thalamocingulate division is largely responsible for mammals’ hunger for family and community connections. There is no reptilian counterpart. Homo sapiens, in fact, have the largest thalamocingulate division in the animal kingdom (Gallagher 179). It is a physical necessity to share common human experiences with one another. If the thalamocingulate division of the limbic system is starved, we literally cease to function correctly. In my classroom, I operate under one basic assumption: that each of the kids that enters through my doorway is, at heart, a decent human being who needs to make connections to the world that surrounds him or her. This is an important assumption because it simultaneously ensures that I do my best to treat them fairly, and it allows me to have certain expectations of their behavior, which then informs my teaching and overall classroom management. I believe that decent human beings do not go out of their way to hurt others. But hurting happens, and when it does, decent human beings act to make what’s wrong right again. So based on this, I aspire to create a safe, open environment for students to share and to make connections both to other human beings—both physical and depicted, and places—again both physical and depicted, they might not have done so originally. It does not matter what medium is being analyzed or enjoyed—a classic novel, a popular movie, a serialized television drama, a comic strip—the creator of that work’s main job is to get people invested in the characters from that world. If the creator of the work fails in that task, then nobody cares about it and it either never gets published/released or fades into oblivion. So these works that high school students are forced to work with, like it or not (and yes, I’m in the “not” category for Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird, and no, I’m never going to like those books) have withstood the test of time and the rigors of criticism. Though I may not particularly enjoy reading or teaching the two works I mentioned, I can appreciate the ability of these authors to construct memorable characters that have become ingrained in our academic culture and popular society. They have become a common human experience in much of America. Not only can a student relate to the youthfulness of a Scout Finch or a Huck Finn (or to the idea of the freedom given from such a wide body of water like the Mississippi), but a goal of presenting and analyzing these works should be to create empathy for characters like Jim or Tom Robinson or the entire town of Maycomb. Writers craft their stories in a variety of ways. Sometimes the characters may be vivid in the writer’s mind before the world, sometimes a world or a place is so exciting that a story begs to be told about it, and the building of people to inhabit this world comes later. Sometimes a writer just fills a notebook or types until it all comes together (Card 63-66). But when analyzing characterization we can look it the craft through the following four lenses: 1. 2. 3. 4. What the character looks like What the character says What the character does What the character thinks or feels Writers create characters through showing, telling, or a combination of the two (LaPlante 423-427). Once students are able to able to see how a writer is enticing you into making that connection, it becomes easier to integrate these principles into one’s own writing. Though crafting believable characters isn’t a large part of the curriculum I teach, literary analysis certainly is. The analysis of characters—their connections with us the readers, with other characters in the work, their motivations, their nuances, their interaction with their environment, etc—is usually a fantastic starting point for fulfilling the requirements of a rigid curricula. Because, what really, is classic literature but an interpretation of the common human condition which simultaneously plagues and blesses us all? Once the methods of characterization are learned, one can then look at his or her self with a critical eye. Even further, one can identify one’s self within the scope of a place-based environment—an environment which provides motivation and freedom to act the way one does. Placing one’s self in this context, one can then apply that lens to analyzing literature through characterization as controlled through one’s environment. Sherman Alexie gives a great example of this in The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. In describing life on the reservation he says, “Poverty doesn’t give you strength or teach you lessons about perseverance. No, poverty only teaches you how to be poor” (13). Often we identify ourselves through our environment, especially when we’re somewhere else. I often interject that I’m from Butte, MT and allow all the connotation that goes along with it because it’s a “different” place, and that’s putting it nicely. This helps to give me an identity separate from those around me. I am unique and have the freedom to act the way I do because of my upbringing in that place, which almost everyone from Montana knows is a character in its own right. The classroom application for teaching characterization of people and place is a fairly simple one, but one that requires trust and a safe community of sharing and openness to be fully optimized. I would propose spending at least two class days (120 minutes minimum) on this topic, but it can certainly be expanded or contracted, depending on time constraints and curricular demands. The invitation to inquiry and writing I would give to kick this off would be for the students to introduce me (and each other) to the person with which they feel the safest. I want the students to simply tell me a little about this person—as much or as little as they want—and I purposely leave the instructions a bit vague so they do not all write me the same thing. Ten minutes is usually a good timeframe in which to complete this first writing activity. Once the students finish, then we would take 5-10 minutes to share, and I simply acknowledge each entry with a “thank you.” This is important because I want to acknowledge each student individually, equally, and I want to honor the fact that they had the courage to share their writing with the whole group. Once the students have shared, I discuss what they have all done, which is characterized their safe person for us. A writer has to not only introduce us to each character in a work, but they must continually define and redefine what it means to be that character. They are constantly introducing us to that person using the four lenses described earlier. It is at this point that I pass out LaPlante’s writing on the four lenses of characterization, and we discuss these elements and how they show up not only in professional writing, but in previous writings the students have completed in their writing notebooks. A topic of discussion that is vital to have with the students before we move on is the advantages and drawbacks of the different forms of media—written (books, magazines, and the like), and visual (TV, movies, comics, etc). The next phase of this unit is looking at different forms of media to examine how writers use characterization techniques to get audiences to connect to their characters. I would split the class into four groups, and assign one lens of characterization to each group. I would encourage another look at Alexie’s novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian. In chapter four of this novel we learn a little more about the main character, and meet his best friend, Rowdy. It is a fantastic example that lends itself to using the four lenses of characterization for analysis. Next I would show a short clip from the popular TV series House, MD. The pilot episode introduces us to the title character, an acerbic, crippled doctor who seems to despise human interaction. The five-minute clip focuses on the character, but mainly through interactions and descriptions from other characters. At the end of this time after giving students the prompt to jot down what they noticed about both pieces, we would share what had the most energy first with small groups, then with the larger group. Once the lenses of characterization are firmly in the minds of students, then it is time to extend the metaphor. Since place can also be a character, the four lenses can also apply to the setting. To show this, I would have the students look at a clip from the 2004 motion picture King Arthur, and again, jot down what they notice. In this clip some of the main characters discuss what the term “home” means to them, and what their role in their particular place is. Once we look at that clip, then we have covered all the main forms of media—books, TV, & film. We return, finally to text to complete the circle, and look at Woody Kipp’s text “Branding” from his book. Once we have identified how these works deal with the characterization of place, I would have the students introduce me to the place they consider “home.” It can be past or present, but again, I want them to introduce the class to their hometown. An extension activity would be to have the students distill their hometown memories into a tagline. For example, Billings’ current tagline is “Montana’s Trailhead,” which is appropriate since Billings is the place you go when you want to go somewhere else, like a trailhead. Then the students will share. Connecting students to characterization of people and places in the forms of media they will examine in school is a great way to help students understand the works as a whole and fulfill a whole slew of curricular requirements as well. Bibliography and Further Reading About Characterization Alexie, Sherman. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. New York: Little, Brown & Company, 2007. Print. Berry, Dave. Dave Berry’s Complete Guide to Guys. New York: Random House, 1995. Print. Card, Orson Scott. Enders Game. New York: Tor Books, 1977. Print. Card, Orson Scott How to Write Science Fiction & Fantasy. Cincinnati, OH: Writer’s Digest Books, 1990. Print. Dean, Nancy. Voice Lessons: Classroom Activities to Teach Diction, Detail, Imagery, Syntax, & More. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House, 2000. Print. Gallagher, Winifred. The Power of Place: How Our Surroundings Shape Our Thoughts, Emotions, and Actions. New York: Harper Perennial/Harper Collins, 1993. Print. Goldberg, Natalie. Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within. Boston: Shambhala, 1986. Print. Halpern, Justin. Sh*t My Dad Says. New York: Harper Collins It Books, 2010. Print Kempton, Gloria. Write Great Fiction: Dialogue. Techniques and Exercises for Crafting Effective Dialogue. Cincinnati, OH: Writer’s Digest Books, 2004. Print. King Arthur. Dir. Antoine Fuqua. Perf. Clive Owen, Kiera Knightley, Ioan Gruffudd. Touchstone, 2004. Film. King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. New York: Pocket Books, 2000. Print. Kipp, Woody. Viet Cong at Wounded Knee: The Trail of a Blackfeet Activist. Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2004. Print. LaPlante, Alice. The Making of a Story: A Norton Guide to Creative Writing. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. Print. Perl, Sondra, & Schuster, Charles, eds. Stepping On My Brother’s Head. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann/Boynton/Cook, 2010. Print. “Pilot Episode.” House, MD. Fox. KHMT, Billings, MT. 16 Nov. 2004. Television. Romano, Tom. Writing With Passion: Life Stories, Multiple Genres. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann/Boynton/Cook, 1995. Print. Simmons, Bill. The Book of Basketball: the NBA According to the Sports Guy. New York: ESPN Books, 2009. Print. Classroom/Demonstration Process - - - - - Intro to self (what I teach & how). Suggest new lens – teacher as human being. (5 minutes) Activity 1: Think about the person/people with which you feel the most safe (the most “decent human being” you know). Tell me a little about this person. You don’t have to give a name if you don’t want to, but in your writers’ notebook, simply introduce me to this person in the manner you see fit. (10 minutes) Sharing time (5-15 minutes) Relate sharing time to characterization, a set of techniques writers use to introduce us to the people they want us to care about—the people we HAVE TO CARE ABOUT OR THEY ARE OUT OF A JOB. Pass out the four aspects of characterization (what ch. looks like, says, does, thinks/feels). Discuss the advantages and drawbacks faced by written media versus visual media. (5 minutes) Activity 2: Split into 4 groups. Pass out Revenge is My Middle Name, by Sherman Alexie. Have each group look at a different aspect of characterization from the passage. Have them jot down what they notice while reading, share in small group, then pick a spokesperson to share for the larger group. (25 minutes) Same groups, different lens. Show clip from House (5 minutes) Share small group, then large group (10 minutes) Relate characterization to place. The rez in Alexie, the island from Lost. Show 4 minute King Arthur clip. Jot down what you notice of the place, and thoughts on what the characters say about “home.” Share. (20 minutes) Share passage from “Branding,” from Kipp. Think about “home.” Try to distill it down to one or two sentences, then share. (25 minutes) Revised Lesson time – 70-120 minutes