The Limits of Mediation for Emerging Powers

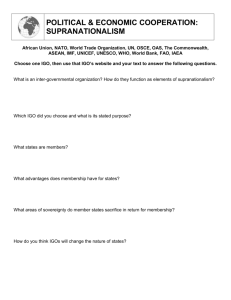

advertisement