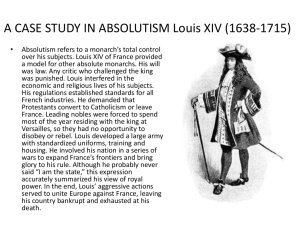

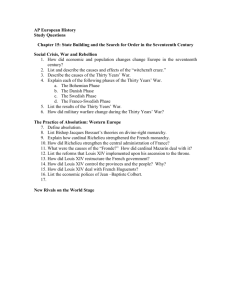

Mckay Chapter Readings

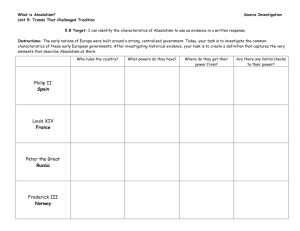

advertisement